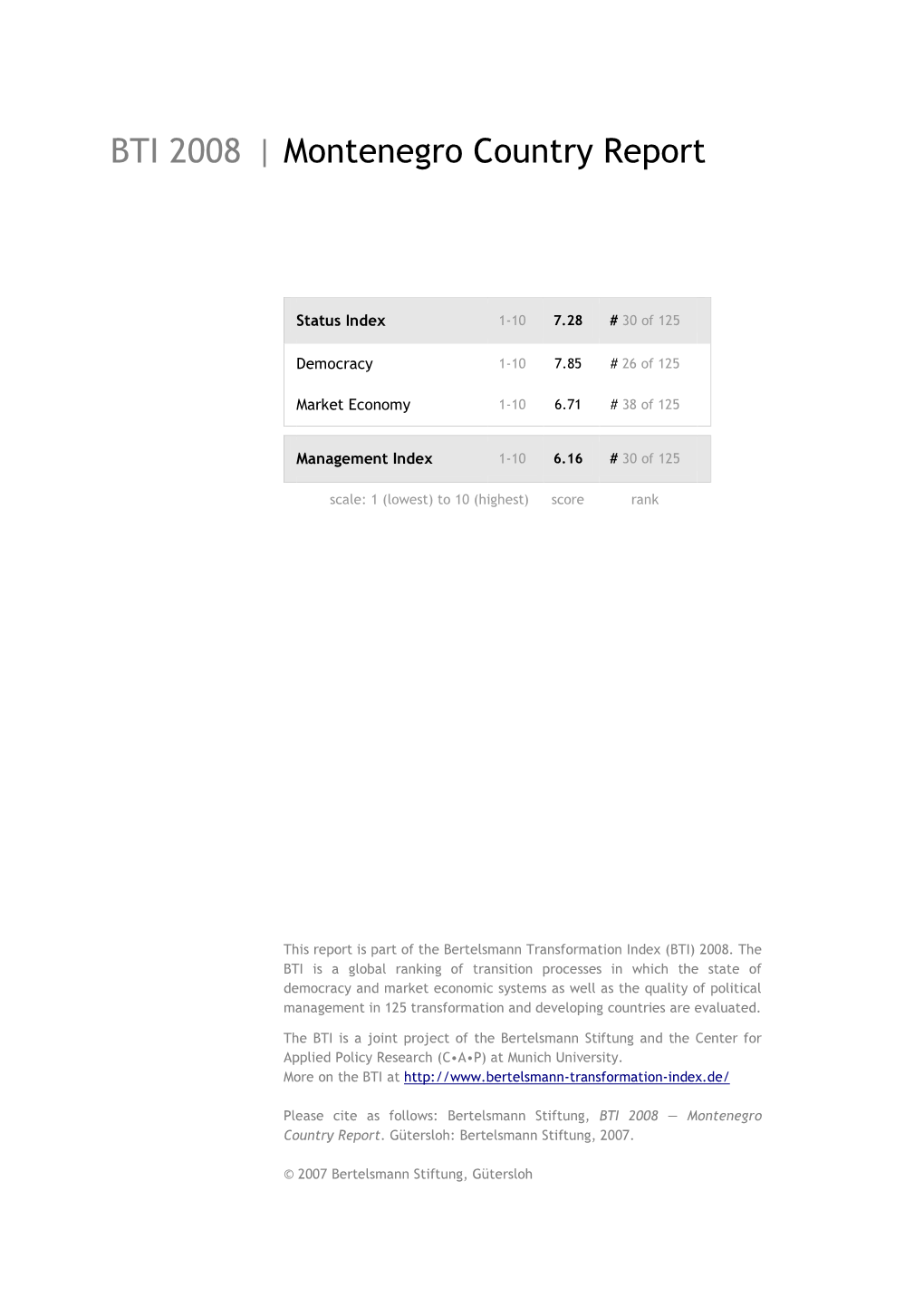

BTI 2008 | Montenegro Country Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESOLVING DISPUTES and BUILDING RELATIONS Challenges of Normalization Between Kosovo and Serbia

Council CIG for Inclusive Governance RESOLVING DISPUTES AND BUILDING RELATIONS Challenges of Normalization between Kosovo and Serbia Contents 2 PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 SUPPORTING THE BRUSSELS DIALOGUE 16 ESTABLISHING THE ASSOCIATION / COMMUNITY OF SERB-MAJORITY MUNICIPALITIES 24 KOSOVO’S NORTH INTEGRATION AND SERB POLITICAL PARTICIPATION 32 PARLIAMENTARY COOPERATION 39 COOPERATION ON EU INTEGRATION 41 PARTICIPANTS Albanian and Serbian translations of this publication are available on CIG’s website at cigonline.net. CIG Resolving Disputes anD BuilDing Relations Challenges of normalization between Kosovo and serbia Council for Inclusive Governance New York, 2015 PrefaCe anD AcknowleDgments Relations between Kosovo and Serbia are difficult. Since Kosovo’s declaration of independence in February 2008, all contacts between officials of Kosovo and Serbia ceased. Belgrade rejected any direct interaction with Pristina preferring to deal through the EU Rule of Law Mission and the UN Mission in Kosovo. However, encouraged by the EU and the US, senior officials of both governments met in March 2011 for direct talks in Brussels. These talks were followed in Brussels in October 2012 by a meeting between the prime ministers of Kosovo and Serbia. These EU-mediated dialogues resulted in a number of agreements between Serbia and Kosovo including the April 2013 Brussels Agreement. The Agreement’s main goal is to conclude the integration of the Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo’s north into Kosovo’s system of laws and governance, including the establishment of the Association/Community of the Serb-Majority Municipalities in Kosovo. The sides also pledged not to block each other’s accession processes into the EU. -

Political Parties of Kosovo Serbs in the Political System of Kosovo: from Pluralism to Monism JOVANA RADOSAVLJEVIĆ & BUDIMIR NIČIĆ 3

1 NEW SOCIALINITIATIVE Political parties of Kosovo Serbs April in the political 2021 system of Kosovo: From pluralism to monism 2 Political parties of Kosovo Serbs in the political system of Kosovo: from pluralism to monism JOVANA RADOSAVLJEVIĆ & BUDIMIR NIČIĆ 3 Characteristics of the open society within Serb community in Kosovo Political Civil society parties of organizations in the Kosovo Serbs in Openness of Serbian Serbian community in the political system media in Kosovo Kosovo – Beteween of Kosovo: From perceptions and pluralism to presentation monism Attitudes of Kosovo Openness of institutions Community Rights in Serbs of security to the citizens of Kosovo Kosovo institutions Analysis of the Kosovo Serbs in the economic situation in dialogue process the Serb-populated areas in Kosovo Research title: Political parties of Kosovo Serbs in the political system of Kosovo: From pluralism to monism Published by: KFOS Prepared by: Nova društvena inicijativa (New Social Initiative) i Medija Centar (Media Center) Authors: Jovana Radosavljević, Budimir Ničić The original writing language of the analysis is Serbian language. Translated by: Biljana Simurdić Design: tedel Printed by (No. of copies): tedel (100) This paper is published within OPEN, a project carried out by the Kosovo Foundation for Open Society (KFOS) in cooperation with the organizations Nova društvena inicijativa (New Social Initiative) and Medija Centar (Media Center). Views expressed in this publication are exclusively those of the research authors and are not necessarily the views of KFOS. Year of publishing: 2021 CONTENT 05. WHO ARE 16 03. IMPORTANT PLAYERS AND POLITICAL PARTIES 9 WHAT ARE THEIR OF KOSOVO SERBS, ROLES FROM PLURALISM TO MONISM 01. -

Kosovo Political Economy Analysis Final Report

KOSOVO POLITICAL ECONOMY ANALYSIS FINAL REPORT DECEMBER 26, 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Management Systems International, A Tetra Tech Company. KOSOVO POLITICAL ECONOMY ANALYSIS FINAL REPORT December 26, 2017 IDIQ No. AID-167-I-17-00002 Award No: AID-167-TO-17-00009 Prepared by Management Systems International (MSI), A Tetra Tech Company 200 12th St South, Suite 1200 Arlington, VA, USA 22202 DISCLAIMER This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the sole responsibility of the Management Systems International and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. CONTENTS Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................... ii Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 6 II. Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 7 A. Foundational Factors ........................................................................................................................................... 7 B. Rules -

(MNEE) Dataset

Montenegrin Elections (MNEE) dataset List of Abbreviations and Names of Parties and Coalitions Last updated: 11 March 2021 If you notice any issues or discrepancies or have questions regarding the table, please send an email to: [email protected] Table Election year Abrreviation Original name Notes and English translation If a party or (coalition partners information on coalition represents in brackets) sources (where a minority, which applicable) minority it represents? 1990 SKCG Savez komunista Crne Future dominant League of Gore party. In 1991 it was Communists of renamed into Montenegro Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS). 1990 SRSJCG (LSCG-SP- Savez reformskih Source: Adžić (2019). Alliance of Yugoslav PSCG-NOK-SNR- snaga Jugoslavije za Reformist Forces for SDSCG-DACG) Crnu Goru Montenegro 1990 LSCG Liberalni savez Crne Liberal Alliance of Gore Montenegro 1990 PSCG Partija socijalista Crne Party of Socialists Gore 1990 SP Socijalistička partija Socialist Party 1990 NOK Nezavisna orgazinacija Independent komunista Organization of Communists 1990 SNR Stranka nacionalne Party of National Bosniak ravnopravnosti Equality 1 1990 SDSCG Socijaldemokratska Not to be confused Social Democratic stranka Crne Gore with SDP (formed in Party of Montenegro 1993) or SDS (Serb Democratic Party)! 1990 DACG Demokratska Democratic alternativa Crne Gore Alternative of Montenegro 1990 DK (SDA-DSCG-SR) Demokratska koalicija Source: Pavićević Democratic coalition Bosniak and Albanian (2007, 25). (coalition, see notes) *details on the members of coalition in -

Southeastern Europe

U.S. ONLINE TRAINING FOR OSCE, INCLUDING REACT Module 5. Southeastern Europe This module introduces you to southeastern Europe and the OSCE’s work in: • Croatia (The OSCE Office in Zagreb was closed in 2012) • Macedonia • Bosnia-Herzegovina • Serbia • Kosovo • Montenegro • Albania . 1 Table of Contents Overview. 3 Geography. 4 People. 6 Former Yugoslavia. 10 World War I. 11 World War II. 12 Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia. 14 Post-Tito. 15 Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. 17 Croatia. 18 Key information. 19 Historical background. 20 During Tito. 21 After Tito. 22 War of independence. 23 Domestic politics. 25 Macedonia. 35 Key information. 36 Historical background. 38 19th and early 20th centuries. 39 During Tito. 41 Independence. 43 Domestic politics. 44 Prospects and challenges. 67 Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH). 72 Key information. 73 Historical background. 75 During the Tito era. 76 The Bosnian war: 1992-1995. 79 Disunity of international community. 81 The Dayton Peace Accords, 1995. 84 Politics since Dayton. 87 Challenges and pressures. 95 Serbia. 99 Key information. 100 Introduction. 101 Contemporary Serbia. 102 Miloševi?'s rise. 104 Domestic resistance and state oppression. 106 Consequences of Kosovo. 109 The short-lived Kosovo Verification Mission. 110 MODULE 5. Southeastern Europe 2 Regime repression intensifies. 112 Struggle for Serbia’s political direction. 115 Nikolic wins 2012 presidential election. 122 Serbia's identity and its vision for the future. 124 Montenegro. 131 Key information. 132 Contemporary Montenegro. 133 Politics in Montenegro. 134 Other issues. 140 Kosovo. 142 Key information. 143 Historical background of Kosovo. 144 Organized non-violence. 145 After Dayton. 147 UNMIK established. -

Kosovo: the Challenge of Transition

KOSOVO: THE CHALLENGE OF TRANSITION Europe Report N°170 – 17 February 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. THE STATE OF PLAY ................................................................................................. 1 A. THE PROCESS SO FAR............................................................................................................1 1. Ahtisaari’s room for manoeuvre................................................................................1 2. Finding the core of the process..................................................................................2 B. UNMIK’S SCORESHEET: KOSOVO AT GROUND LEVEL .........................................................3 1. Standards....................................................................................................................3 2. The political system...................................................................................................4 3. The economy and institutions....................................................................................5 4. Policing......................................................................................................................6 5. Inter-ethnic relations and security..............................................................................7 II. THE PROTAGONISTS ............................................................................................... 10 A. THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY .....................................................................................10 -

Montenegro Integration Perspectives and Synergic Effects Of

Integration Perspectives and Synergic Effects of European Transformation in the Countries Targeted by EU Enlargement and Neighbourhood Policies Montenegro Jelena Džankiü Jadranka Kaluÿeroviü, Ivana Vojinoviü, Ana Krsmanoviü, Milica Dakoviü, Gordana Radojeviü, Ivan Jovetiü, Vojin Goluboviü, Mirza Muleškoviü, Milika Mirkoviü, ISSP – Institute for Strategic Studies and Prognosis Bosiljka Vukoviü June 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 POLITICAL TRANSFORMATION PROCESS IN MONTENEGRO ............. 4 1.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 5 1.2 The Creation of Democratic Institutions and Their Functioning ............................. 7 1.2.1 Political institutions in Montenegro throughout history: the effect of political traditions on the development of democratic institutions................................................ 7 1.2.2 The constitutional establishment of Montenegro .......................................... 12 1.2.3 Observations ................................................................................................ 26 1.3 The Implementation of the EU’s Democratic Requirements................................. 27 1.3.1 Transparency ............................................................................................... 27 1.3.2 Decision-making processes .......................................................................... 29 1.3.3 Minority rights............................................................................................ -

Political History of the Balkans (1989–2018) This Page Intentionally Left Blank POLITICAL HISTORY of the BALKANS (1989–2018) Edited by József Dúró – Zoltán Egeresi

The Balkan Peninsula has played a crucial role in human history many times. The region framed the 20th century. The end of the Political History of the Balkans Cold War also had a significant effect on the region as it resulted (1989–2018) in bloody wars, economic collapse and complicated political transitions. The 2000s and 2010s opened the way towards EU membership, as many countries received candidate status and launched accession negotiations – however, this process has recently been facing obstacles. Political History This volume provides a general overview of the Post-Cold War history of the Balkans and explores the dynamics behind these tremendous changes ranging from democratic transitions to EU prospects. The authors describe the transitional period, the evolution of the political system and highlight the most important of the Balkans political developments in each country in the region. We recommend this book to those who seek a deeper insight into the recent history of the Balkans and a deeper understanding of its political developments. (1989–2018) POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE BALKANS (1989—2018) POLITICAL HISTORY The work was created in commission of the National University of Public Service under the priority project PACSDOP-2.1.2-CCHOP-15-2016-00001 entitled “Public Service Development Establishing Good Governance”. Zoltán Egeresi (eds.): Egeresi Zoltán — József Dúró József Edited by JÓZSEF DÚRÓ European Social Fund ZOLTÁN EGERESI INVESTING IN YOUR FUTURE Political History of the Balkans (1989–2018) This page intentionally left blank POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE BALKANS (1989–2018) Edited by József Dúró – Zoltán Egeresi Dialóg Campus Budapest, 2020 The work was created in commission of the National University of Public Service under the priority project PACSDOP-2.1.2-CCHOP-15-2016-00001 entitled “Public Service Development Establishing Good Governance”. -

Majority and Minority Ethnic Voting in New Democracies

Identity and Agency: Majority and Minority Ethnic Voting in New Democracies Benjamin P. McClelland Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 Benjamin P. McClelland All Rights Reserved Abstract Identity and Agency: Majority and Minority Ethnic Voting in New Democracies Benjamin P. McClelland This dissertation examines how ethnic identities are politicized through elections in new democracies. Using the cases of post-communist Latvia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, I compare the electoral success of campaigns which appeal to voters on the basis of ethnicity to those do not. I argue that ethnic parties are most likely in groups for whom two conditions are met. First, ethnicity must meaningfully differentiate ethnic insiders from outsiders, in such a way that voters will believe policy benefits will likely result from political representation for the group. Second, electoral institutions must ensure that the political mobilization of the group will result in electoral victory. These two conditions create fundamentally different incentives for ethnic majority groups and ethnic minority groups simply because of differences in group size. In most democracies with a large minority population, ethnic voting will be more likely among the majority group than the minority group, unless institutions encourage minority group voting by lowering barriers to entry. The results demonstrate the qualitatively different ways groups use ethnic identities as a resource to achieve political objectives, with important implications for minority group representation, political participation, and democratic governance in diverse societies. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Why Study Ethnic Voting? . -

Kosovo Status: Delay Is Risky

KOSOVO STATUS: DELAY IS RISKY Europe Report N°177 – 10 November 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. THE STATUS EQUATION........................................................................................... 1 A. AHTISAARI’S WORK...............................................................................................................2 B. FUTURE INTERNATIONAL PRESENCE .......................................................................................7 1. The International Community Representative..............................................................7 2. The EU Rule-of-Law Mission.....................................................................................9 3. Transition..................................................................................................................11 II. ON THE GROUND ...................................................................................................... 12 A. ALBANIANS ........................................................................................................................12 1. Management of the negotiations................................................................................12 2. Status expectations....................................................................................................13 3. Ground-level politics.................................................................................................15 B. SERBS .................................................................................................................................16 -

English Version Remains the Only Official Document

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights MONTENEGRO EARLY PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 29 March 2009 OSCE/ODIHR Election Observation Mission Final Report Warsaw 10 June 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................... 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................... 3 III. POLITICAL CONTEXT.......................................................................................................................... 3 IV. ELECTION SYSTEM AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK ......................................................................... 4 A. ELECTION SYSTEM AND GENERAL FRAMEWORK .................................................................................... 4 B. LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR VOTING .......................................................................................................... 6 V. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION .......................................................................................................... 7 A. STRUCTURE AND COMPOSITION OF ELECTION ADMINISTRATION ............................................................ 7 B. ORGANIZATION OF ELECTIONS ................................................................................................................ 8 VI. VOTER REGISTRATION ...................................................................................................................... 9 VII. CANDIDATE REGISTRATION............................................................................................................11 -

Kosovo by Krenar Gashi

Kosovo by Krenar Gashi Capital: Pristina Population: 1.8 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$9,870 Source: World Bank World Development Indicators. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2017 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 National Democratic 5.50 5.25 5.50 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 Governance Electoral Process 4.50 4.50 4.25 4.50 5.00 5.00 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.75 Civil Society 4.00 4.00 3.75 3.75 3.75 4.00 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 Independent Media 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.25 5.00 Local Democratic 5.50 5.25 5.00 5.00 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.50 4.50 Governance Judicial Framework 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.75 5.75 5.50 and Independence Corruption 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.00 5.75 Democracy Score 5.21 5.14 5.07 5.18 5.18 5.25 5.14 5.14 5.07 4.96 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. If consensus cannot be reached, Freedom House is responsible for the final ratings. The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest.