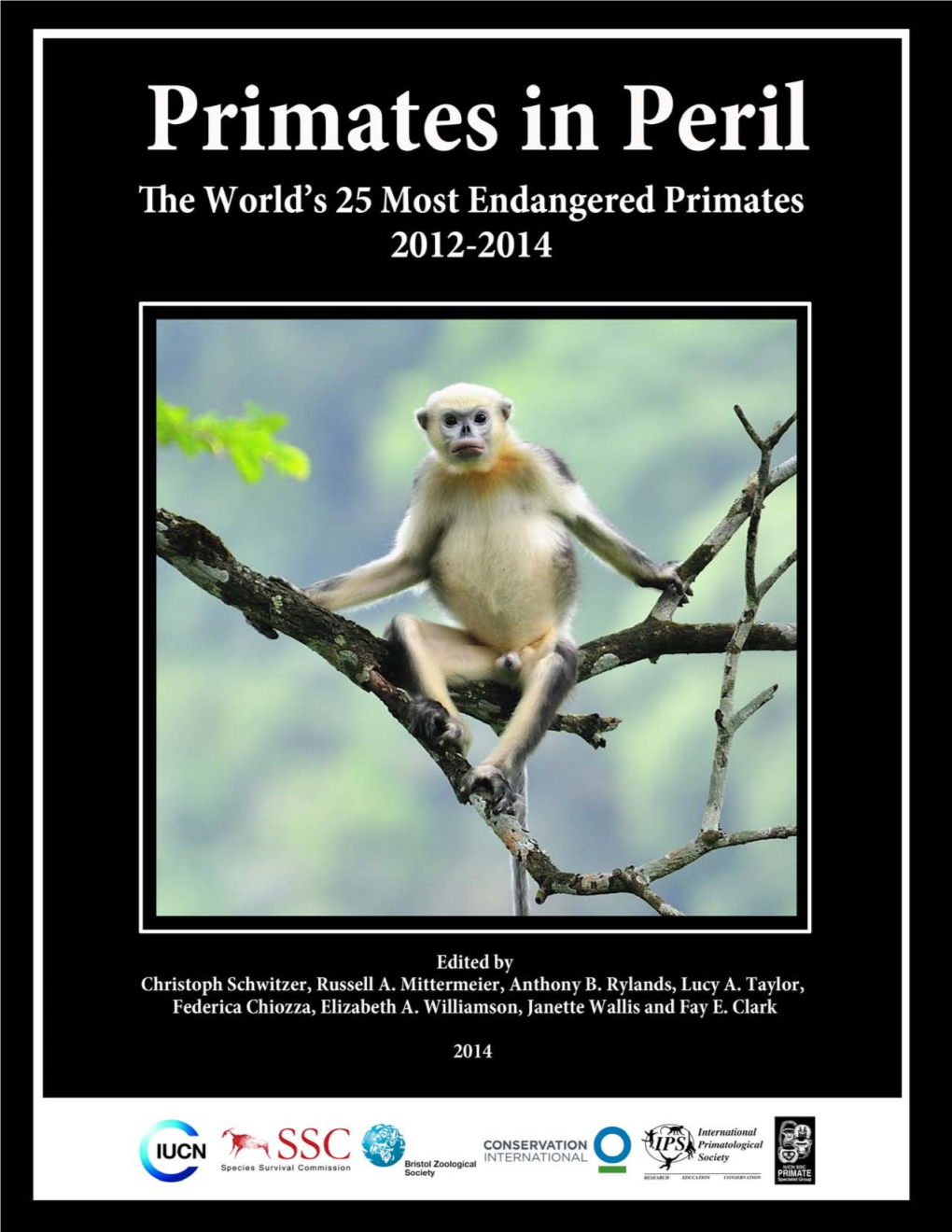

The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates 2012–2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Body Measurements for the Monkeys of Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea

Primate Conservation 2009 (24): 99–105 Body Measurements for the Monkeys of Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea Thomas M. Butynski¹,², Yvonne A. de Jong² and Gail W. Hearn¹ ¹Bioko Biodiversity Protection Program, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA ²Eastern Africa Primate Diversity and Conservation Program, Nanyuki, Kenya Abstract: Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea, has a rich (eight genera, 11 species), unique (seven endemic subspecies), and threat- ened (five species) primate fauna, but the taxonomic status of most forms is not clear. This uncertainty is a serious problem for the setting of priorities for the conservation of Bioko’s (and the region’s) primates. Some of the questions related to the taxonomic status of Bioko’s primates can be resolved through the statistical comparison of data on their body measurements with those of their counterparts on the African mainland. Data for such comparisons are, however, lacking. This note presents the first large set of body measurement data for each of the seven species of monkeys endemic to Bioko; means, ranges, standard deviations and sample sizes for seven body measurements. These 49 data sets derive from 544 fresh adult specimens (235 adult males and 309 adult females) collected by shotgun hunters for sale in the bushmeat market in Malabo. Key Words: Bioko Island, body measurements, conservation, monkeys, morphology, taxonomy Introduction gordonorum), and surprisingly few such data exist even for some of the more widespread species (for example, Allen’s Comparing external body measurements for adult indi- swamp monkey Allenopithecus nigroviridis, northern tala- viduals from different sites has long been used as a tool for poin monkey Miopithecus ogouensis, and grivet Chlorocebus describing populations, subspecies, and species of animals aethiops). -

Low Paternity Skew and the Influence of Maternal Kin in an Egalitarian

Low paternity skew and the influence of maternal kin in an egalitarian, patrilocal primate Karen B. Striera,1, Paulo B. Chavesb, Sérgio L. Mendesc, Valéria Fagundesc, and Anthony Di Fioreb,d aDepartment of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706; bDepartment of Anthropology and Center for the Study of Human Origins, New York University, New York, NY 10003; cDepartamento de Ciências Biológicas, Centro de Ciências Humanas e Naturais, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Maruipe, Vitória, ES 29043-900, Brazil; and dDepartment of Anthropology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712 Contributed by Karen B. Strier, October 12, 2011 (sent for review September 11, 2011) Levels of reproductive skew vary in wild primates living in The fecal samples used for paternity analyses included the 22 multimale groups depending on the degree to which high-ranking infants born between 2005 and 2007 that survived to ≥2.08 y of males monopolize access to females. Still, the factors affecting age, their 21 mothers (representing diverse ages and histories) paternity in egalitarian societies remain unexplored. We combine (Table S1), and the 24 adult males that were possible sires of at unique behavioral, life history, and genetic data to evaluate the least one infant (Table S2). We considered a male to be a po- distribution of paternity in the northern muriqui (Brachyteles tential sire for an infant if he was >5 y and was known to have hypoxanthus), a species known for its affiliative, nonhierarchical completed a copulation before the infant’s estimated conception relationships. We genotyped 67 individuals (22 infants born over a date (birth date minus mean 216.4-d gestation) (16). -

Primates of the Southern Mentawai Islands

Primate Conservation 2018 (32): 193-203 The Status of Primates in the Southern Mentawai Islands, Indonesia Ahmad Yanuar1 and Jatna Supriatna2 1Department of Biology and Post-graduate Program in Biology Conservation, Tropical Biodiversity Conservation Center- Universitas Nasional, Jl. RM. Harsono, Jakarta, Indonesia 2Department of Biology, FMIPA and Research Center for Climate Change, University of Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia Abstract: Populations of the primates native to the Mentawai Islands—Kloss’ gibbon Hylobates klossii, the Mentawai langur Presbytis potenziani, the Mentawai pig-tailed macaque Macaca pagensis, and the snub-nosed pig-tailed monkey Simias con- color—persist in disturbed and undisturbed forests and forest patches in Sipora, North Pagai and South Pagai. We used the line-transect method to survey primates in Sipora and the Pagai Islands and estimate their population densities. We walked 157.5 km and 185.6 km of line transects on Sipora and on the Pagai Islands, respectively, and obtained 93 sightings on Sipora and 109 sightings on the Pagai Islands. On Sipora, we estimated population densities for H. klossii, P. potenziani, and S. concolor in an area of 9.5 km², and M. pagensis in an area of 12.6 km². On the Pagai Islands, we estimated the population densities of the four primates in an area of 11.1 km². Simias concolor was found to have the lowest group densities on Sipora, whilst P. potenziani had the highest group densities. On the Pagai Islands, H. klossii was the least abundant and M. pagensis had the highest group densities. Primate populations, notably of the snub-nosed pig-tailed monkey and Kloss’ gibbon, are reduced and threatened on the southern Mentawai Islands. -

Diets of Howler Monkeys

Chapter 2 Diets of Howler Monkeys Pedro Américo D. Dias and Ariadna Rangel-Negrín Abstract Based on a bibliographical review, we examined the diets of howler mon- keys to compile a comprehensive overview of their food resources and document dietary diversity. Additionally, we analyzed the effects of rainfall, group size, and forest size on dietary variation. Howlers eat nearly all available plant parts in their habitats. Time dedicated to the consumption of different food types varies among species and populations, such that feeding behavior can range from high folivory to high frugivory. Overall, howlers were found to use at least 1,165 plant species, belonging to 479 genera and 111 families as food sources. Similarity in the use of plant taxa as food sources (assessed with the Jaccard index) is higher within than between howler species, although variation in similarity is higher within species. Rainfall patterns, group size, and forest size affect several dimensions of the dietary habits of howlers, such that, for instance, the degree of frugivory increases with increased rainfall and habitat size, but decreases with increasing group size in groups that live in more productive habitats. Moreover, the range of variation in dietary habits correlates positively with variation in rainfall, suggesting that some howler species are habitat generalists and have more variable diets, whereas others are habi- tat specialists and tend to concentrate their diets on certain plant parts. Our results highlight the high degree of dietary fl exibility demonstrated by the genus Alouatta and provide new insights for future research on howler foraging strategies. Resumen Con base en una revisión bibliográfi ca, examinamos las dietas de los monos aulladores para describir exhaustivamente sus recursos alimenticios y la diversidad de su dieta. -

In Situ Conservation

NEWSN°17/DECEMBER 2020 Editorial IN SITU CONSERVATION One effect from 2020 is for sure: Uncertainty. Forward planning is largely News from the Little Fireface First, our annual SLOW event was impossible. We are acting and reacting Project, Java, Indonesia celebrated world-wide, including along the current situation caused by the By Prof K.A.I. Nekaris, MA, PhD by project partners Kukang Rescue Covid-19 pandemic. All zoos are struggling Director of the Little Fireface Project Program Sumatra, EAST Vietnam, Love economically after (and still ongoing) Wildlife Thailand, NE India Primate temporary closures and restricted business. The Little Fireface Project team has Investments in development are postponed Centre India, and the Bangladesh Slow at least. Each budget must be reviewed. been busy! Despite COVID we have Loris Project, to name a few. The end In the last newsletter we mentioned not been able to keep up with our wild of the week resulted in a loris virtual to forget about the support of the in situ radio collared slow lorises, including conference, featuring speakers from conservation efforts. Some of these under welcoming many new babies into the the helm of the Prosimian TAG are crucial 11 loris range countries. Over 200 for the survival of species – and for a more family. The ‘cover photo’ you see here people registered, and via Facebook sustainable life for the people involved in is Smol – the daughter of Lupak – and Live, more than 6000 people watched rd some of the poorest countries in the world. is our first 3 generation birth! Having the event. -

Habitat Suitability for Primate Conservation in North-East Brazil

Habitat suitability for primate conservation in north-east Brazil B ÁRBARA M ORAES,ORLY R AZGOUR,JOÃO P EDRO S OUZA-ALVES J EAN P. BOUBLI and B RUNA B EZERRA Abstract Brazil has a high diversity of primates, but in- Introduction creasing anthropogenic pressures and climate change could influence forest cover in the country and cause fu- razil is home to species of non-human primates ture changes in the distribution of primate populations. B(Estrada et al., ; Costa-Araújo et al., ; IUCN, Here we aim to assess the long-term suitability of habitats ), of which occur in the Atlantic Forest, Cerrado for the conservation of three threatened Brazilian primates and Caatinga biomes in the north-east. These three biomes (Alouatta belzebul, Sapajus flavius and Sapajus libidinosus) have been extensively modified by centuries of anthropo- through () estimating their current and future distributions genic forest destruction for the development of agriculture, using species distribution models, () evaluating how much infrastructure and urban areas. Primate populations are in of the areas projected to be suitable is represented within sharp decline, including the most charismatic, elusive and protected areas and priority areas for biodiversity conser- rare species. Half of the primate species in north-east Brazil vation, and () assessing the extent of remaining forest cov- are under threat, including five species categorized as er in areas predicted to be suitable for these species. We Endangered and five categorized as Critically Endangered found that % of the suitable areas are outside protected on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, ). areas and only % are located in areas with forest cover. -

MAHAJANGA BV Reçus: 246 Sur 246

RESULTATS SENATORIALES DU 29/12/2015 FARITANY: 4 MAHAJANGA BV reçus: 246 sur 246 INDEPE TIM MANAR AREMA MAPAR HVM NDANT ANARA : FANILO N°BV Emplacement AP AT Inscrits Votants B N S E ASSOCI REGION 41 BETSIBOKA BV reçus 39 sur 39 DISTRICT: 4101 KANDREHO BV reçus7 sur 7 01 AMBALIHA 0 0 6 6 0 6 0 0 0 1 0 5 02 ANDASIBE 0 0 6 6 0 6 0 2 0 0 0 4 03 ANTANIMBARIBE 0 0 6 6 0 6 0 2 0 0 1 3 04 BEHAZOMATY 0 0 6 6 0 6 0 3 0 0 0 3 05 BETAIMBOAY 0 0 6 5 0 5 0 1 0 0 0 4 06 KANDREHO 0 0 6 6 0 6 0 3 0 0 0 3 07 MAHATSINJO SUD 0 0 6 5 0 5 0 0 0 0 0 5 TOTAL DISTRICT 0 0 42 40 0 40 0 11 0 1 1 27 DISTRICT: 4102 MAEVATANANA BV reçus19 sur 19 01 AMBALAJIA 0 0 6 5 0 5 0 2 0 0 2 1 02 AMBALANJANAKOMBY 0 0 6 6 0 6 0 2 0 0 1 3 03 ANDRIBA 0 0 8 8 0 8 0 2 0 0 2 4 04 ANTANIMBARY 0 0 8 8 0 8 0 1 0 0 0 7 05 ANTSIAFABOSITRA 0 0 8 8 0 8 0 3 0 0 0 5 06 BEANANA 0 0 6 5 0 5 0 1 0 0 0 4 07 BEMOKOTRA 0 0 6 6 0 6 0 3 0 0 1 2 08 BERATSIMANINA 0 0 6 6 0 6 0 0 0 0 0 6 09 BERIVOTRA 5/5 0 0 6 5 0 5 0 1 0 0 0 4 10 MADIROMIRAFY 0 0 6 6 0 6 0 1 0 0 1 4 11 MAEVATANANA I 0 0 10 9 0 9 0 3 0 0 2 4 12 MAEVATANANA II 0 0 8 8 0 8 0 2 0 0 0 6 13 MAHATSINJO 0 0 8 8 0 8 0 0 0 0 0 8 14 MAHAZOMA 0 0 8 8 0 8 0 2 0 0 2 4 15 MANGABE 0 0 8 7 0 7 0 1 0 0 1 5 16 MARIA 0 0 6 5 0 5 0 1 0 0 1 3 17 MAROKORO 0 0 6 6 0 6 0 2 0 0 0 4 18 MORAFENO 0 0 6 3 0 3 0 3 0 0 0 0 19 TSARARANO 0 0 8 8 0 8 0 3 0 0 2 3 TOTAL DISTRICT 0 0 134 125 0 125 0 33 0 0 15 77 DISTRICT: 4103 TSARATANANA BV reçus13 sur 13 01 AMBAKIRENY 0 0 8 8 0 8 0 4 0 0 0 4 02 AMPANDRANA 0 0 6 6 0 6 0 3 0 0 0 3 03 ANDRIAMENA 0 0 8 7 0 7 0 4 0 0 0 3 04 -

(Malagasy Tia Tanindrazana) GAST

NOMBRE DISTRICT COMMUNE ENTITE NOM ET PRENOM(S) CANDIDATS CANDIDATS ANALALAVA AMBALIHA 1 MATITA (Malagasy Tia Tanindrazana) GASTON RAZAFINARIVO MICHEL (Indépendant Razafinarivo ANALALAVA AMBALIHA 1 RASANDILINE Feline Michel) ANALALAVA AMBARIJEBY SUD 1 MATITA (Malagasy Tia Tanindrazana) FERDINAND GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRD (Isika Rehetra Miaraka @ ANALALAVA AMBARIJEBY SUD 1 ANDRIAMAHERY Housnah Bechara Ayate Andry Rajoelina) ANALALAVA AMBARIJEBY SUD 1 VINCENT (Inedependant Vincent) VINCENT ANALALAVA AMBOLOBOZO 1 MATITA (Malagasy Tia Tanindrazana) ANICET ANALALAVA AMBOLOBOZO 1 IRD (Isika Rehetra Miaraka @ Andry Rajoelina) TOMBOMISY Jean Rasidy ANALALAVA ANALALAVA 1 MATITA (Malagasy Tia Tanindrazana) AMADA GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRD (Isika Rehetra Miaraka @ ANALALAVA ANALALAVA 1 JEAN Baptiste Andry Rajoelina) FANJAVA VELOGNO (Independant Fanjava ANALALAVA ANALALAVA 1 VELOMANANA Firmin Velogno) ANALALAVA ANDRIBAVONTSINA 1 IRD (Isika Rehetra Miaraka @ Andry Rajoelina) JAOHEVITRY Richard ANALALAVA ANDRIBAVONTSINA 1 MATITA (Malagasy Tia Tanindrazana) TAVANDRAINA Parfait ANALALAVA ANDRIBAVONTSINA 1 ROZELA (Indépendant Rozela) ROZELA ANALALAVA ANGOAKA SUD 1 IRD (Isika Rehetra Miaraka @ Andry Rajoelina) TSARAFARA Jean Denis ANALALAVA ANGOAKA SUD 1 MATITA (Malagasy Tia Tanindrazana) SERGE Rochin RANDRIANJAFIMANANA GHISLAIN (Independant ANALALAVA ANKARAMY 1 RASENDRAHASINA Jeannot Randrianjafimanana Ghislain) VONINOSY SUZANE (Independant Voninosy ANALALAVA ANKARAMY 1 MISIZARA Béatrice Suzanne) ANALALAVA ANKARAMY 1 IRD (Isika Rehetra Miaraka @ Andry Rajoelina) -

Lemur Bounce!

Assets – Reections Icon Style CoverAssets Style – Reections 1 Icon Style Y E F O N Cover StyleR O M M R A A Y E F D O N C A S R O GA M M R A D A AGASC LemurVISUAL Bounce! BRAND LearningGuidelines and Sponsorship Pack VISUAL BRAND Guidelines 2 Lemur Bounce nni My name is Lennie Le e Bounce with me B .. ou and raise money to n c protect my Rainforest e L ! home! L MfM L 3 What is a Lemur Bounce? A Lemur Bounce is a sponsored event for kids to raise money by playing bouncing games. In this pack: * Learning fun for kids including facts and quizzes Indoor crafts and outside bouncing games for * the Lemur Bounce Day * Links to teaching resources for schools * Lesson planning ideas for teachers * Everything you need for a packed day of learning and fun! Contents Fun Bounce activities Page No. Let’s BounceBounce – YourLemur valuable support 5 n n Lemur Bouncee i e L – Basics 7 B u o Planningn for a Lemur Bounce Day 8 c L e Lemur! Bounce Day Assembly 8 Make L a Lemur Mask 9 Make a Lemur Tail & Costume 10 Games 11-12 Sponsorship Forms 13-14 Assets – Reections M f Certificates 15-20 Icon Style M Cover Style L Y E F O N R Fun Indoor activities O M M R A Planning your lessons for a Lemur Bounce Day 22 D A A SC GA Fun Facts about Madagascar 23 Fun Facts about Lemurs 24 Colouring Template 25 VISUAL BRAND Guidelines Word Search 26 Know your Lemurs 27 Lemur Quiz 28 Madagascar Quiz 29-31 Resources 32 Song and Dance 33 Contact us 34 LEMUR BOUNCE BOUNCE fM FOR MfM LEMUR BASICS Y NE FO O R WHAT ‘LEM OUNC“ ‘ DO YOU KNOW YOUR LEMUR M Have you ever seen a lemur bounce? Maaasar is ome to over 0 seies o endemi lemurs inluding some M very ouncy ones lie the Siaa lemur ut tese oreous rimates are highl endangere e need to at R Let’s Bounce - Your valuable support A no to sae teir aitat and rotect tem rom etin tion arity Mone or Maaasar is alling out to A D C Wherechildren does everywhere the money to organizego? a fun charity ‘lemur bounce’. -

Colobus Angolensis Palliatus) in an East African Coastal Forest

African Primates 7 (2): 203-210 (2012) Activity Budgets of Peters’ Angola Black-and-White Colobus (Colobus angolensis palliatus) in an East African Coastal Forest Zeno Wijtten1, Emma Hankinson1, Timothy Pellissier2, Matthew Nuttall1 & Richard Lemarkat3 1Global Vision International (GVI) Kenya 2University of Winnipeg, Winnipeg, Canada 3Kenyan Wildlife Services (KWS), Kenya Abstract: Activity budgets of primates are commonly associated with strategies of energy conservation and are affected by a range of variables. In order to establish a solid basis for studies of colobine monkey food preference, food availability, group size, competition and movement, and also to aid conservation efforts, we studied activity of individuals from social groups of Colobus angolensis palliatus in a coastal forest patch in southeastern Kenya. Our observations (N = 461 hours) were conducted year-round, over a period of three years. In our Colobus angolensis palliatus study population, there was a relatively low mean group size of 5.6 ± SD 2.7. Resting, feeding, moving and socializing took up 64%, 22%, 3% and 4% of their time, respectively. In the dry season, as opposed to the wet season, the colobus increased the time they spent feeding, traveling, and being alert, and decreased the time they spent resting. General activity levels and group sizes are low compared to those for other populations of Colobus spp. We suggest that Peters’ Angola black-and-white colobus often live (including at our study site) under low preferred-food availability conditions and, as a result, are adapted to lower activity levels. With East African coastal forest declining rapidly, comparative studies focusing on C. -

World's Most Endangered Primates

Primates in Peril The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands, Federica Chiozza, Elizabeth A. Williamson, Elizabeth J. Macfie, Janette Wallis and Alison Cotton Illustrations by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG) International Primatological Society (IPS) Conservation International (CI) Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Copyright: ©2017 Conservation International All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA. Citation (report): Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B., Chiozza, F., Williamson, E.A., Macfie, E.J., Wallis, J. and Cotton, A. (eds.). 2017. Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. 99 pp. Citation (species): Salmona, J., Patel, E.R., Chikhi, L. and Banks, M.A. 2017. Propithecus perrieri (Lavauden, 1931). In: C. Schwitzer, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, F. Chiozza, E.A. Williamson, E.J. Macfie, J. Wallis and A. Cotton (eds.), Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018, pp. 40-43. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. -

Mandrillus Leucophaeus Poensis)

Ecology and Behavior of the Bioko Island Drill (Mandrillus leucophaeus poensis) A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Jacob Robert Owens in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2013 i © Copyright 2013 Jacob Robert Owens. All Rights Reserved ii Dedications To my wife, Jen. iii Acknowledgments The research presented herein was made possible by the financial support provided by Primate Conservation Inc., ExxonMobil Foundation, Mobil Equatorial Guinea, Inc., Margo Marsh Biodiversity Fund, and the Los Angeles Zoo. I would also like to express my gratitude to Dr. Teck-Kah Lim and the Drexel University Office of Graduate Studies for the Dissertation Fellowship and the invaluable time it provided me during the writing process. I thank the Government of Equatorial Guinea, the Ministry of Fisheries and the Environment, Ministry of Information, Press, and Radio, and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism for the opportunity to work and live in one of the most beautiful and unique places in the world. I am grateful to the faculty and staff of the National University of Equatorial Guinea who helped me navigate the geographic and bureaucratic landscape of Bioko Island. I would especially like to thank Jose Manuel Esara Echube, Claudio Posa Bohome, Maximilliano Fero Meñe, Eusebio Ondo Nguema, and Mariano Obama Bibang. The journey to my Ph.D. has been considerably more taxing than I expected, and I would not have been able to complete it without the assistance of an expansive list of people. I would like to thank all of you who have helped me through this process, many of whom I lack the space to do so specifically here.