Religious Patterns in Contemporary Rhetorical Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danielson, Killingly & Its Villages Vol

PRSRT STD POSTAL U.S. POSTAGE PAID CUSTOMER PERMIT #231 ECR WSS SOUTHBRIDGE, MA 01550 Mailed to every home in Brooklyn, the borough of Danielson, Killingly & its villages Vol. II, No.10 Complimentary (860) 928-1818/email:[email protected] "A friend in the market is better than money in the chest." Friday, February 1, 2008 East Killingly Fire District plans new station Towns BY JOSH SAYLES They are unelected officials who VILLAGER STAFF WRITER tax independently of Killingly and gear up EAST KILLINGLY — The East have the ability to put a lien on an Killingly Fire District is planning individual’s property if taxes are to build a new fire station, a propos- not paid. al that has some residents con- Some East Killingly residents cerned about the price tag and the believe that the solution for the for primary need for such a facility. firehouse lies within expansion of The cost is estimated by some the current facility, not a new residents to be as much as $1.4 mil- building. lion, and citizens aware of the situ- Stevens disagreed. He said that election ation have raised several concerns the expansion, for what the depart- ment currently needs, would cost BY BRAD TILLES about the funding of the project. VILLAGER STAFF WRITER East Killingly Fire District approximately $700,000, not includ- President George Stevens, however, ing the cost of bringing the current The upcoming Connecticut said the cost of the project could building up to code. Furthermore, Presidential Primary is fast not yet be determined. the original building was built in approaching on Feb. -

ASK LANCE TOLAND Let’S Focus on Giving Transition Pilots All the Help They Need

WHY PRESSURE PATTERNS MAKE THE MOST SENSE WINTER 2017 PILATUS OWNERS AND PILOTS ASSOCIATION CHANGES IN THE AIR WHEN ATC ALTERS THE GAME PLAN AT THE LAST MINUTE ALONE IN THE COCKPIT When no one’s there to catch your errors PLUS FLYING YOUR PC-12 FLTPLAN GO JUST FROM SPACE GETS BETTER Surprising how much we do and say Great new features keep coming is now coming from a satellite Power, Performance, and Prestige The New Structural Composite 5-blade STC for Pilatus PC-12 The Pilatus PC-12 has earned its reputation for outstanding versatility, performance, reliability, and operational flexibility. The new Hartzell 5-blade composite STC raises it to a whole new level. The numbers speak for themselves: 〉 2-3 knots improved cruise speed 〉 Over 10% shorter takeoff roll 〉 Up to 100 feet per minute better climb rate A BOLD STATEMENT DOESN’T NEED TO MAKE NOISE. For 2017, the Pilatus PC-12 NG launches bolder than ever. We’ve partnered with Designworks, a BMW Group Company, to offer six modern and elegant interior designs, each tailored to a Now available for immediate delivery and installation. unique style and attitude – yours. The new PC-12 NG’s composite five-blade propeller makes Contact your local Pilatus Sales & Service Center for details, the cabin even quieter and the ride even smoother. After all, great style is never loud. or visit hartzellprop.com Pilatus Business Aircraft Ltd • +1 303 465 9099 • www.pilatus-aircraft.com PIL0117_POPA_BoldStatement.indd 1 2/3/2017 8:21:56 AM Power, Performance, and Prestige The New Structural Composite 5-blade STC for Pilatus PC-12 The Pilatus PC-12 has earned its reputation for outstanding versatility, performance, reliability, and operational flexibility. -

Full Results of Survey of Songs

Existential Songs Full results Supplementary material for Mick Cooper’s Existential psychotherapy and counselling: Contributions to a pluralistic practice (Sage, 2015), Appendix. One of the great strengths of existential philosophy is that it stretches far beyond psychotherapy and counselling; into art, literature and many other forms of popular culture. This means that there are many – including films, novels and songs that convey the key messages of existentialism. These may be useful for trainees of existential therapy, and also as recommendations for clients to deepen an understanding of this way of seeing the world. In order to identify the most helpful resources, an online survey was conducted in the summer of 2014 to identify the key existential films, books and novels. Invites were sent out via email to existential training institutes and societies, and through social media. Participants were invited to nominate up to three of each art media that ‘most strongly communicate the core messages of existentialism’. In total, 119 people took part in the survey (i.e., gave one or more response). Approximately half were female (n = 57) and half were male (n = 56), with one of other gender. The average age was 47 years old (range 26–89). The participants were primarily distributed across the UK (n = 37), continental Europe (n = 34), North America (n = 24), Australia (n = 15) and Asia (n = 6). Around 90% of the respondents were either qualified therapists (n = 78) or in training (n = 26). Of these, around two-thirds (n = 69) considered themselves existential therapists, and one third (n = 32) did not. There were 235 nominations for the key existential song, with enormous variation across the different respondents. -

Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1St Edition)

R O C K i n t h e R E S E R V A T I O N Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1st edition). (text, 2004) Yngvar B. Steinholt. New York and Bergen, Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. viii + 230 pages + 14 photo pages. Delivered in pdf format for printing in March 2005. ISBN 0-9701684-3-8 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt (b. 1969) currently teaches Russian Cultural History at the Department of Russian Studies, Bergen University (http://www.hf.uib.no/i/russisk/steinholt). The text is a revised and corrected version of the identically entitled doctoral thesis, publicly defended on 12. November 2004 at the Humanistics Faculty, Bergen University, in partial fulfilment of the Doctor Artium degree. Opponents were Associate Professor Finn Sivert Nielsen, Institute of Anthropology, Copenhagen University, and Professor Stan Hawkins, Institute of Musicology, Oslo University. The pagination, numbering, format, size, and page layout of the original thesis do not correspond to the present edition. Photographs by Andrei ‘Villi’ Usov ( A. Usov) are used with kind permission. Cover illustrations by Nikolai Kopeikin were made exclusively for RiR. Published by Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. 401 West End Avenue # 3B New York, NY 10024 USA Preface i Acknowledgements This study has been completed with the generous financial support of The Research Council of Norway (Norges Forskningsråd). It was conducted at the Department of Russian Studies in the friendly atmosphere of the Institute of Classical Philology, Religion and Russian Studies (IKRR), Bergen University. -

Sociological Papers the Emerging Second Generation of Immigrant

Sociological Papers The Emerging Second Generation of Immigrant Israelis Series Editor: Larissa Remennick Managing Editor: Anna Prashizky Volume 16, 2011 Sponsored by the Leon Tamman Foundation for Research into Jewish Communities SOCIOLOGICAL INSTITUTE FOR COMMUNITY STUDIES BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Generation 1.5 Russians in Israel: From Vodka to Latte. Maturation and Integration Processes as Reflected in the Recreational Patterns Liza Rozovsky and Oz Almog The Department of Land of Israel Studies University of Haifa Abstract This article reflects on the process of coming of age among Russian Israelis who immigrated as older children or adolescents. It describes the culture of informal youth groups (tusovkas) of the 1990s that transplanted multiple elements of Russian subversive youth culture of the last Soviet and post-Soviet years onto Israeli soil. These groups - that flourished mainly in peripheral towns of Israel - served as both social safety net for alienated Russian teenagers and the bridge to their gradual acculturation. Entering adulthood, most tusovka members left the streets, completed their academic degrees, and moved to Central Israel in search of lucrative jobs and thriving cultural life. Although young Russian Israelis have adopted many elements of the mainstream lifestyle (particularly in the patterns of residence and entertainment), their social preferences and identity remain distinct in lieu of the lingering Russian cultural legacies. Introduction This article sheds light on the recent changes in the recreational patterns of "Generation 1.5" – Russian, Ukrainian and other former Soviet immigrants who immigrated in Israel along with their parents as preteens or young adolescents during the 1990s. Several factors shaped the recreational patterns of these Generation 1.5'ers during their initial years in Israel: the social characteristics of the Russian aliyah; the unique circumstances of their birth and socialization; and the policies of direct immigrant absorption first instituted in Israel during the 1990s. -

L'italia E L'eurovision Song Contest Un Rinnovato

La musica unisce l'Europa… e non solo C'è chi la definisce "La Champions League" della musica e in fondo non sbaglia. L'Eurovision è una grande festa, ma soprattutto è un concorso in cui i Paesi d'Europa si sfidano a colpi di note. Tecnicamente, è un concorso fra televisioni, visto che ad organizzarlo è l'EBU (European Broadcasting Union), l'ente che riunisce le tv pubbliche d'Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Noi italiani l'abbiamo a lungo chiamato Eurofestival, i francesi sciovinisti lo chiamano Concours Eurovision de la Chanson, l'abbreviazione per tutti è Eurovision. Oggi più che mai una rassegna globale, che vede protagonisti nel 2016 43 paesi: 42 aderenti all'ente organizzatore più l'Australia, che dell'EBU è solo membro associato, essendo fuori dall'area (l’anno scorso fu invitata dall’EBU per festeggiare i 60 anni del concorso per via dei grandi ascolti che la rassegna fa in quel paese e che quest’anno è stata nuovamente invitata dall’organizzazione). L'ideatore della rassegna fu un italiano: Sergio Pugliese, nel 1956 direttore della RAI, che ispirandosi a Sanremo volle creare una rassegna musicale europea. La propose a Marcel Bezençon, il franco-svizzero allora direttore generale del neonato consorzio eurovisione, che mise il sigillo sull'idea: ecco così nascere un concorso di musica con lo scopo nobile di promuovere la collaborazione e l'amicizia tra i popoli europei, la ricostituzione di un continente dilaniato dalla guerra attraverso lo spettacolo e la tv. E oltre a questo, molto più prosaicamente, anche sperimentare una diretta in simultanea in più Paesi e promuovere il mezzo televisivo nel vecchio continente. -

Reform and Human Rights the Gorbachev Record

100TH-CONGRESS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES [ 1023 REFORM AND HUMAN RIGHTS THE GORBACHEV RECORD REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES BY THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE MAY 1988 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1988 84-979 = For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE STENY H. HOYER, Maryland, Chairman DENNIS DeCONCINI, Arizona, Cochairman DANTE B. FASCELL, Florida FRANK LAUTENBERG, New Jersey EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts TIMOTHY WIRTH, Colorado BILL RICHARDSON, New Mexico WYCHE FOWLER, Georgia EDWARD FEIGHAN, Ohio HARRY REED, Nevada DON RITTER, Pennslyvania ALFONSE M. D'AMATO, New York CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey JOHN HEINZ, Pennsylvania JACK F. KEMP, New York JAMES McCLURE, Idaho JOHN EDWARD PORTER, Illinois MALCOLM WALLOP, Wyoming EXECUTIvR BRANCH HON. RICHARD SCHIFIER, Department of State Vacancy, Department of Defense Vacancy, Department of Commerce Samuel G. Wise, Staff Director Mary Sue Hafner, Deputy Staff Director and General Counsel Jane S. Fisher, Senior Staff Consultant Michael Amitay, Staff Assistant Catherine Cosman, Staff Assistant Orest Deychakiwsky, Staff Assistant Josh Dorosin, Staff Assistant John Finerty, Staff Assistant Robert Hand, Staff Assistant Gina M. Harner, Administrative Assistant Judy Ingram, Staff Assistant Jesse L. Jacobs, Staff Assistant Judi Kerns, Ofrice Manager Ronald McNamara, Staff Assistant Michael Ochs, Staff Assistant Spencer Oliver, Consultant Erika B. Schlager, Staff Assistant Thomas Warner, Pinting Clerk (11) CONTENTS Page Summary Letter of Transmittal .................... V........................................V Reform and Human Rights: The Gorbachev Record ................................................ -

0Sustainable Development Report

DEVELOPMENT REPORT DEVELOPMENT SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT REPORT SUSTAINABLE 20 20 20 20 # CONTENTS About the Report 2 Message from MTS PJSC President 6 Message from the Chairperson of the ESG Committee 8 Message from the Chairperson of the Sustainable Development and CSR Committee 10 WeAreTogether# COVID 12 MTS Ecosystem Sustainable Development Management 18 Management 40 Business Model 19 Sustainable Development and CSR Strategy 42 Our Markets 22 Sustainable Development Network Infrastructure and ESG Management System 54 Development 32 MTS’s Corporate Responsibility Open Innovations 36 Principles 62 Financial Results 38 1 Responsibility Contacts 171 and Priorities 78 For Shareholders – Openness Appendices 173 and Transparency 80 Achievements 174 For customers – Systematic Approach and Consistency 84 Membership of Associations and Organizations 178 For Personnel – Responsiveness and Care 100 Public Certification of the Report 179 For Partners and Suppliers – GRI Content Index 180 Trust and Cooperation 122 For the State – Reliability and Scale 128 For Local Communities – Support and Development 132 Environmental Responsibility 158 [102-43] [102-44] [102-46] [102-47] [103-1] MTS Group presents its 13th Industrialists and Entrepreneurs obtained in the framework of public Sustainable Development certification of the 2019 Report were used. Report. The business strategy of MTS Customer Lifetime Value MTS runs regular surveys of key stakeholder groups to identify 2.0, focused on building long- the most relevant topics to be addressed in greater detail. The term, sustainable relationships final assessment of the significance of the topic for inclusion in with customers and partners, the Report is also influenced by a comprehensive analysis of the including through the provision Company’s representatives service on public and state committees, of better customer service management decisions, strategic priorities approved by the Board of and the development of an Directors, and the issues raised during regular IR events. -

Murlafortesmontse Treball.Pdf 2.123 Mb

Índex Nota .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Agraïments ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Introducció ....................................................................................................................................... 2 L’arribada de la Perestroika ............................................................................................................. 3 Els joves com a agents socials ......................................................................................................... 6 Moviments culturals renovats i joves a la URSS ............................................................................. 9 L’era post-soviètica ........................................................................................................................ 19 El nou cinema per a la nova Rússia ............................................................................................... 21 Aleksei Balabanov, director ........................................................................................................... 25 Ressorgiment del cinema negre ..................................................................................................... 31 “Brother”: més que gàngster, nou heroi rus ................................................................................... 33 “Brother 2”, -

Eurovision Karaoke

1 Eurovision Karaoke ALBANÍA ASERBAÍDJAN ALB 06 Zjarr e ftohtë AZE 08 Day after day ALB 07 Hear My Plea AZE 09 Always ALB 10 It's All About You AZE 14 Start The Fire ALB 12 Suus AZE 15 Hour of the Wolf ALB 13 Identitet AZE 16 Miracle ALB 14 Hersi - One Night's Anger ALB 15 I’m Alive AUSTURRÍKI ALB 16 Fairytale AUT 89 Nur ein Lied ANDORRA AUT 90 Keine Mauern mehr AUT 04 Du bist AND 07 Salvem el món AUT 07 Get a life - get alive AUT 11 The Secret Is Love ARMENÍA AUT 12 Woki Mit Deim Popo AUT 13 Shine ARM 07 Anytime you need AUT 14 Conchita Wurst- Rise Like a Phoenix ARM 08 Qele Qele AUT 15 I Am Yours ARM 09 Nor Par (Jan Jan) AUT 16 Loin d’Ici ARM 10 Apricot Stone ARM 11 Boom Boom ÁSTRALÍA ARM 13 Lonely Planet AUS 15 Tonight Again ARM 14 Aram Mp3- Not Alone AUS 16 Sound of Silence ARM 15 Face the Shadow ARM 16 LoveWave 2 Eurovision Karaoke BELGÍA UKI 10 That Sounds Good To Me UKI 11 I Can BEL 86 J'aime la vie UKI 12 Love Will Set You Free BEL 87 Soldiers of love UKI 13 Believe in Me BEL 89 Door de wind UKI 14 Molly- Children of the Universe BEL 98 Dis oui UKI 15 Still in Love with You BEL 06 Je t'adore UKI 16 You’re Not Alone BEL 12 Would You? BEL 15 Rhythm Inside BÚLGARÍA BEL 16 What’s the Pressure BUL 05 Lorraine BOSNÍA OG HERSEGÓVÍNA BUL 07 Water BUL 12 Love Unlimited BOS 99 Putnici BUL 13 Samo Shampioni BOS 06 Lejla BUL 16 If Love Was a Crime BOS 07 Rijeka bez imena BOS 08 D Pokušaj DUET VERSION DANMÖRK BOS 08 S Pokušaj BOS 11 Love In Rewind DEN 97 Stemmen i mit liv BOS 12 Korake Ti Znam DEN 00 Fly on the wings of love BOS 16 Ljubav Je DEN 06 Twist of love DEN 07 Drama queen BRETLAND DEN 10 New Tomorrow DEN 12 Should've Known Better UKI 83 I'm never giving up DEN 13 Only Teardrops UKI 96 Ooh aah.. -

Antti Okko Punainen Aalto

Antti Okko Punainen Aalto – venäläisrokkarit Yhdysvalloissa 1986–1991 Maisteritutkielma Yleinen historia Historian ja etnologian laitos Jyväskylän Yliopisto Kevät 2020 JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanistis-yhteiskuntatieteellinen tiedekunta Historia Tekijä – Author Antti Okko Työn nimi – Title Punainen aalto – venäläisrokkarit Yhdysvalloissa 1986–1991 Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Yleinen historia Pro -gradu tutkielma Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages Toukokuu 2020 89 Tiivistelmä – Abstract Venäläisen populaarimusiikin suosio venäjänkielisen maailman ulkopuolella on ollut äärimmäisen heikkoa. Kuvaavaa on, että 144-miljoonaisen kansan menestys kansainvälisillä listoilla on jäänyt pahoin jälkeen esimerkiksi suomalaisartistien saavuttamasta kaupallisesta menestyksestä. Menestys on karttanut venäläisiä erityisesti Yhdysvalloissa, populaarikulttuurin kiistattomassa suurvallassa. Yhdysvalloissa Venäjä ja venäläisyys on perinteisesti edustanut toiseutta, ja maa onkin nähty Yhdysvaltojen itsensä peilikuvana, mikä myös heijastuu tapaan, jolla venäläisiin suhtaudutaan. Tutkimuksessani tarkastelen missä määrin venäläisten artistien heikko menestys selittyy yhdysvaltalaisten tavalla tulkita venäläisiä. Käsittelen aihetta Boris Grebenshikovin, Gorky Parkin ja Zvuki Mun kautta, jotka kaikki yrittivät läpimurtoa Yhdysvalloissa vuosien 1986–1991 välillä. Vaikka kyseiset artistit olivat tyyliltään hyvin erilaisia, oli suhtautuminen heihin Yhdysvalloissa todella samankaltaista. Keskeinen lähdeaineistoni -

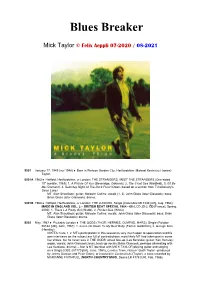

Mick Taylor © Felix Aeppli 07-2020 / 08-2021

Blues Breaker Mick Taylor © Felix Aeppli 07-2020 / 08-2021 5001 January 17, 1949 (not 1948) Born in Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire: Michael Kevin (not James) Taylor. 5001A 1963 Hatfield, Hertfordshire, or London: THE STRANGERS, MEET THE STRANGERS (One-sided 10" acetate, 1963): 1. A Picture Of You (Beveridge, Oakman), 2. The Cruel Sea (Maxfield), 3. It’ll Be Me (Clement), 4. Saturday Night At The Duck Pond (Owen, based on a section from Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake) MT, Alan Shacklock: guitar; Malcolm Collins: vocals (1, 3); John Glass (later Glascock): bass; Brian Glass (later Glascock): drums. 5001B 1964 Hatfield, Hertfordshire, or London: THE JUNIORS, Single (Columbia DB 7339 [UK], Aug. 1964); MADE IN ENGLAND VOL. 2 – BRITISH BEAT SPECIAL 1964 - 69 (LCD 25-2, CD [France], Spring, 2000): 1. There’s A Pretty Girl (Webb), 2. Pocket Size (White) MT, Alan Shacklock: guitar; Malcolm Collins: vocals; John Glass (later Glascock): bass; Brian Glass (later Glascock): drums. 5002 May, 1967 Probably London THE GODS (THOR, HERMES, OLMPUS, MARS), Single (Polydor 56168 [UK], June, 1967): 1. Come On Down To My Boat Baby (Farrell, Goldstein), 2. Garage Man (Hensley) NOTES: Cuts 1, 2: MT’s participation in this session is very much open to speculation and his own interviews on the subject are full of contradictions; most likely MT had taken part in some live shows, but he never was in THE GODS’ actual line-up (Lee Kerslake: guitar; Ken Hensley: organ, vocals; John Glascock: bass, back-up vocals; Brian Glascock, perhaps alternating with Lee Kerslake: drums); – Nor is MT identical with MICK TAYLOR playing guitar and singing on a Single (CBS 201770 [UK], June, 1965), London Town, Hoboin’ (both Taylor - produced by Jimmy Duncan and Peter Eden); or involved in Cockleshells (Taylor), a track recorded by MARIANNE FAITHFULL (NORTH COUNTRY MAID, Decca LK 4778 [UK], Feb.