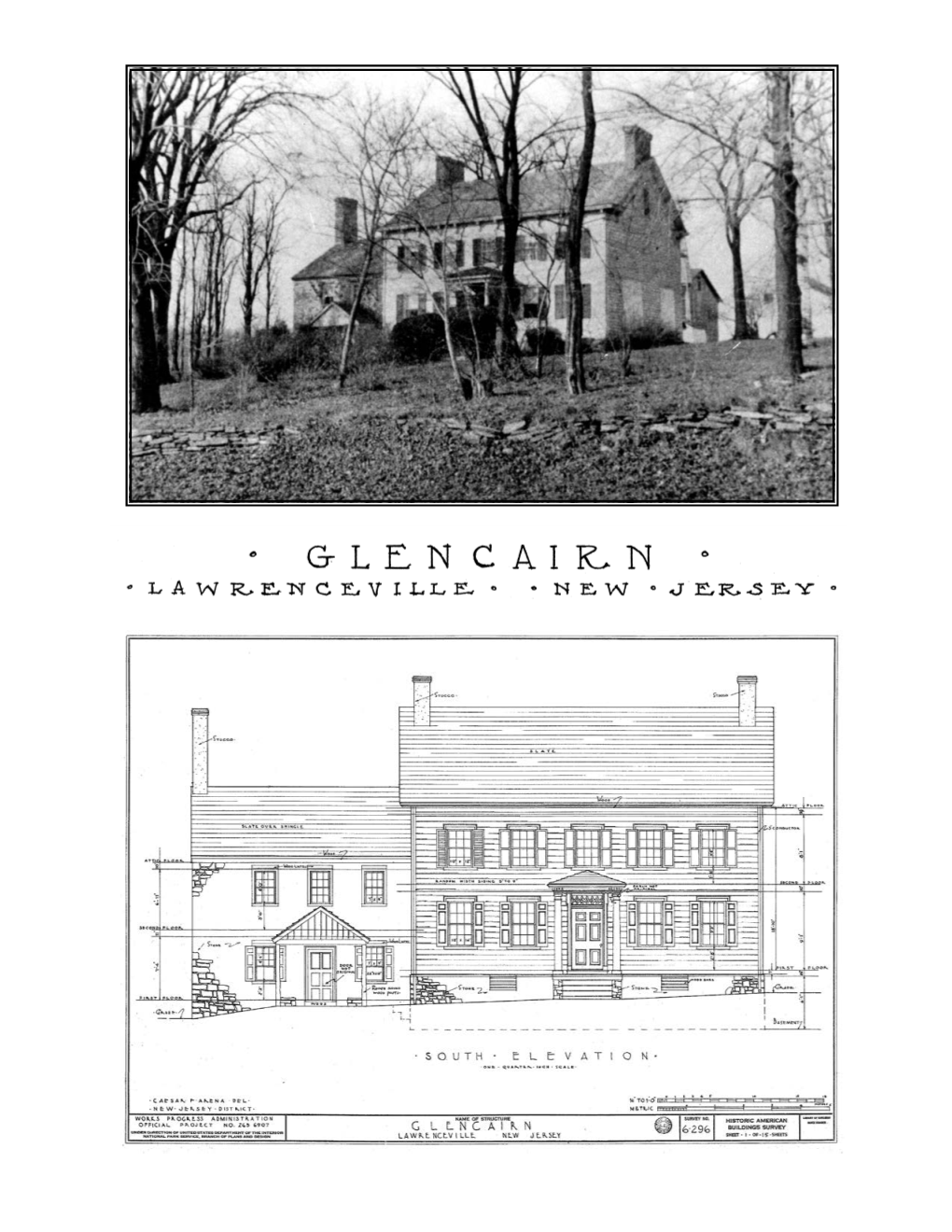

Glencairn N.J. History Symposium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Material World, Memory, and the Making of William Penn's Pennsylvania, 1681--1726

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2011 Building and Planting: The Material World, Memory, and the Making of William Penn's Pennsylvania, 1681--1726 Catharine Christie Dann Roeber College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Roeber, Catharine Christie Dann, "Building and Planting: The Material World, Memory, and the Making of William Penn's Pennsylvania, 1681--1726" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623350. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-824s-w281 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Building and Planting: The Material World, Memory, and the Making of William Penn's Pennsylvania, 1681-1726 Catharine Christie Dann Roeber Oxford, Pennsylvania Bachelor of Arts, The College of William and Mary, 1998 Master of Arts, Winterthur Program in Early American Culture, University of Delaware, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History The College of William and Mary August, 2011 Copyright © 2011 Catharine Dann Roeber All rights reserved APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ac#t~Catharine ~t-r'~~ Christie Dann Roeber ~----- Committee Chair Dr. -

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9227/pennsylvania-county-histories-2549227.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

s-fi Q*M,? P 3 nu V IS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniacoun15unse r * • M /V R K TWAIN’S scRap moK. P*A TENTS: UNITED STATES. GREAT BRITAIN. June 24TH, 1873. May i6th, 1877. May i 8th, 1877. TRADE M ARKS : UNITED STATES. GREAT BRITAIN. Registered No. 5,896. Registered No. 15,979. DIRECTIONS. Use but little moisture, and only on 'the gummed lines. Press the scran on without wetting it. DANIEL SLOTE & COMPANY, NEW YORK. ,vv / BUCKS COUNTY HISTORICAL MONUMENT AT TAYLORSVILLE. From,. The exercises began at 2 o'clock with music | by the Dollngton band. Genera W. W. H. I Davis, of D ylestown. President of tiie so- " 41 ‘ ,oiety, after prayer had been offered by Dev. Alphonse Dare, of Yardlesv introduced G.m- feral Wil iam S. Stryker, of Trenton, who de¬ livered an address, recalling the incidents surrounding Washington's cr issiug of the Date, Delaware and tire battle of Trenton. General Stryker’s Address. General Stryker depicted in a graphic man. ner the horrible suffering of the Continental i troops on lhat. Christinas day, the depression of the people that so little had been accom¬ f WASHINGTON’S CROSSING. plished, and the feasting and revel of the Hessian soldiers at their Trenton encamp¬ ment. He then told of the supper and coun¬ THE PLACE ON THE DELAWARE cil of Washington’s staff oa Ciiflsirms eve, in S imuel Merrick’s house, on the Newtown f MARKED BY IMPOSING MONUMENTS. -

The English Settlers in Colonial Pennsylvania. 317

The English Settlers in Colonial Pennsylvania. 317 THE ENGLISH SETTLERS IN COLONIAL PENNSYLVANIA. BY WAYLAND FULLER DUNAWAY, Ph.D. The Pennsylvania State College. Though the English were the dominant racial ele- ment in colonial Pennsylvania, no one has hitherto been at pains to tell the story of this race, as such, in the settlement of the province. A large number of monographs and articles have been written to describe the migrations, settlements and achievements of other elements of the population, such as the Germans, the Scotch-Irish, the Welsh, and the Swedes, but the Eng- lish have been strangely neglected. It would appear that the English of Pennsylvania take themselves for granted, and hence have not felt called upon to write up their own history. Again, they have not been so race-conscious and clannish as some others have been, but rather have been content to dispense with the hy- phen and to become thoroughly Americanized in thought and feeling. Even so, in view of the consid- erable body of literature describing the other original elements of the population and the almost total lack of such literature devoted specifically to the English, it would seem to be in order to give at least a brief sur- vey of the English settlements in the provincial era. For the purposes of this article the colonial period will be construed as extending to 1790, partly because it is a convenient stopping place, and partly because by so doing it is possible to incorporate some of the data gleaned from the first census. No attempt is here made to give an extended treatment of the subject, but merely to call attention to some of its salient fea- tures. -

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0998/pennsylvania-county-histories-4630998.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

9 ^%6\\ S'. i»j> Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniacoun13unse / I Page B Page c INDEX Page s Page S Pase‘ ■ s . ■ j ' T , ' | U V . w : . ■ «_ - 2 w w XYZ 1 v. , — ---"T«... mmm ■■ •„. - ' 1— . -. - 4 L 3 ready to i os tor and encourage.. His aptness and early promise of talent >G COLLEGE AG must have been noticed by the ministers in the Presbytery in which she resided, NOTABLE EVENTS OF THE OLD TIME. and each and every ono of thorn must have _ rendered valuable aid in teaching him the languages which he mastered thoroughly An Interesting tetter From Our Focal before he attained his fifteenth year. Historian, Samuel Evans, Esq —Some On May 20, 1729, Charles Clinton, an Points Worthy of Careful uncle of the subject of this sketch, and a Perusal. number of friends, chartered a ship, in which the widow of Christian Clinton and her son Charles were also taken to emi¬ The ‘‘Log College” celebration at Nesh- grate to America. aminy.a few days ago, recalls the name of On the voyage the captain attempted to one of the students of that historic place. starve the passengers and get possession of their property, several died, among The name has been kept green in my whom vtas a son arid daughter of Mr. -

Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania

PUBLICATIONS OF THE GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA. Vol. I. 1896. No. 2. WILLS PROVED AT PHILADELPHIA, 1682— 1692. No. 1. THOMAS FREAM,1 of “ Avon, in the County of Gloster,” being sick in body. (Signed with his mark.) Dated 5 September, 1682. Proved 10th of 8 month, 1682, by John Somers and Thomas Madox. ( Christopher Taylor, Regr. Genl.) He appoints as his Executrix, Anne Knight. Bequeathes unto Giles Knight money owing him by James Crafts, beiDg £6. Unto Thomas Knight, brother of Giles Knight, £6, owing by Giles Knight. The residue of his estate to his loving friend, Anne Knight. Witnesses: John Somers, Thomas Madox (his mark), Thomas Williams (his mark), William Herrin (his mark). 1 Thomas Fream ap|«ars to have settled in Bucks County. The inventory of his estate, dated Bucks County, was filed by William Biles and Robert Lucas, “ ye 7th day of ye 12th month, 1682,” and remains with the will in the Register’s Office at Philadelphia. His goods were valued at £28 4s. 6d. “in England,” and 50 per cent.added in the Province, making a total of £42 6s.9ti. This item is of interest because it shows a gross profit of 50 per cent, on im¬ ported goods in the year 1682. (45) 46 Wills proved at Philadelphia, 1682-1692. No. 2. JSAACK MARTIN, of City of Philadelphia, Bolt- maker. Dated 24 November, 1682. Proved 5 month,18th, 1683, by John Goodson and John Sibley. ( Christopher Taylor, Regr. Gail.) All of his lands, being 500 acres in Pennsylvania, to his wife Katherine Martin, in fee simple. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (PMHB), LXXII (1948), 226

PennsylvaniTHE a Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Speaker of the House Pennsylvania, 1701-1776 HE constitutional history of America in the colonial period is the history of the remodeling of English governmental in- Tstitutions to fit the particular circumstances of new societies in the new world. One such transformed institution was the office of speaker of the house as it emerged in the various lower legislative assemblies in the American colonies. The speakership became politi- cally powerful in Pennsylvania and elsewhere in British America at the same time that it lost its partisan character in the House of Commons. There the long Whig hegemony, the appearance of the cabinet system of government, and the scrupulous probity amount- ing to genius of the Great Speaker Arthur Onslow (1727-1761) com- bined to create in the speakership the majestically nonpartisan office we know today.1 The American speakers, however, played a 1 Early speakers were under the influence of the Crown, for whom they generally acted as agents in the House of Commons. Speaker Lenthall's refusal to comply with Charles I's demand that he expose the five members whose arrest the king had ordered signalled a shift from subservience to the king to the House itself. See Edward Porritt, The Unreformed House of Commons (Cambridge, 1903), I, 432-482; J. R. Tanner, English Constitutional Conflicts of the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge, 1966), 114-115; Joseph Redlich, The Procedure of the House of Commons (London, 1907), II, 131-172. See also Basil Williams, The Whig Supremacy 3 4 THOMAS WENDEL January dual role. -

New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol 24

96JCNHAL-CK3Y COL-L^CTIOS* ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 01779 4493 GENEALOGY 974.7 N424NB 1893 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from Allen Country Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/newyorkgenealog24gree THE NEW YORK Genealogical and Biographical feCANTitE LiBRARX DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF AMERICAN GENEALOGY AND BIOGRAPHY. ISSUED QUARTERLY. VOLUME XXIV., 1893 F- fyM «)'S PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY, Berkeley Lyceum, No. 23 West 44.TH Street, NEW YORK CITY. R : •V 63b»71 Publication Committee Mr. THOMAS G. EVANS. Dr. SAMUEL S. FURPLE. Kev. BEVERLEY R. BETTS. Mr. EDWARD F. DE LANCE? Pres» of J. J. Little & Co.. Astor Place, New York INDEX OF SUBJECTS. Alricks, Peter, of the Amsterdam Colony. Geo. Hannah, 125. Baptisms, Reformed Dutch Church Records, N. Y. C, iS, 71, 117, 162. Baptism?, East Hampton, L. I., 183. Brookhaven. L'. I. Abstracts of Wills, SS, 142. Bucks County, Pa. Extracts from Wills, 81. Collegiate Dutch Reformed Church Records, iS, 71, 117, 162. Darling, Gen. Chas. W. Antoine L'Espenard, 97. Donations to Library, 4S. 96. Covers No. 3 and 4. Du Bois, Abram. Memoir, with Pedigree. S. S. Purple, M.D., 153. East Hampton, L. I. Baptisms, 133. Fairfax Families of America, 38. Fishkill Inscriptions, 26. Genealogy. Crommelin, 67. Genealogy, Quackenbos, 173. Genealogy, Schuerman, 132. Genealogy, Ver Planck, 59, 60. Hannah, Geo. Peter Alricks, 125. Hempstead. L. I. Marriages, 79. Huguenot Builders of New Jersey. J. C. Pumpelly, 49. Islip, L. I. Original Patent of Saghtekoos Manor, 146. In the days of 1S13. A letter from Marie Antoinette Nichols, 179. -

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7898/pennsylvania-county-histories-8217898.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

Q7l l <P v 16 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth-Libraries https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniacoun16unse MARK TW^HSTS PATENT 281-657. TRADE MARKS: UNITED STATES. , GREAT BRITAIN. Registered No. 5,896. Registered No. 15,979. DIRECTIONS. » ' * Use but little moisture, and only on the gummed lines. Press the scrap on without wetting it. DANIEL SLOTE & COMPANY, NEW YORK. uv w w XYZ Simultaneous with their arrival be¬ gan the I organization of the Presby¬ terian church, and frequently of i [schools in connection therewith. The [early records furnish abundant evi- jdence of their zeal, the purity of their | (lives, and their earnest effort to foster ! tin the minds of the young a‘reverence (for Divine teachings, and a due respect ■for our peculiar institutions. Their (piety, and their rigid enforcement of law and order in their section .stands out in strong contrast with the lawless¬ ness of the frontier settlements of later days. In writing anything like an authentic and connected history of the early Scotch-Irish settlers of America, the historian will find the way beset with difficulties. Unlike his Quaker contem¬ porary, who was most careful and | painstaking in such matters, the early Some of the Early Settlers Scotch-Irishman appears to have re¬ garded the preservation of family data ‘ in Bucks County. as of minor importance, and the rec- ! ords of the early churches have either (been lost or appropriated by the de¬ A Paper by Warren S. -

The Most Distinguished Surname Byles

Escomb Saxon Church The Most Distinguished Surname Byles Certificate No.3467552017224 Copyright 1998-2017 Swyrich Corporation. All Rights Reserved www.houseofnames.com 888-468-7686 Table of Contents Surname History Origins 3 Ancient History 3 Spelling Variations 3 Early History 3 Early Notables 4 Life in Ireland 4 The Great Migration 5 Current Notables 5 Historic Events 6 Surname Symbolism Introduction 8 Motto 9 Shield 9 Crest 12 Further Readings and Bibliography Appendix - Notable List 13 Appendix - Historic Event List 15 Appendix - Settler List 16 Bibliography 18 Citations 22 Certificate No.3467552017224 Copyright 1998-2017 Swyrich Corporation. All Rights Reserved www.houseofnames.com 888-468-7686 Origins The name Byles is rooted in the ancient Anglo-Saxon culture. It is a name for someone who works as a maker of polearms or halberds and billhooks as these were common weapons in early times. The name could also be a baptismal name derived from son of William, although this latter origin is less likely. Ancient History While your recent ancestors and famous people bearing your surname may be known to you, it is often a family's distant past which fades into the unknown over the centuries. Research has shown that this surname is of Anglo-Saxon origin. Few cultures have had the lasting impact on English society as that of the Anglo-Saxons. The Byles family history draws upon this heritage as the bearers of the name influenced and were influenced by the history of the English nation. Historians have carefully scrutinized such ancient manuscripts as the Domesday Book, compiled in 1086 A.D., the Ragman Rolls (1291-1296), the Curia Regis Rolls, the Pipe Rolls, the Hearth Rolls, parish registers, baptismals, tax records and other ancient documents and found the first record of the name Byles in Somerset, where they held a family seat from ancient times, long before the Norman Conquest in 1066. -

Biles Island

Biles Island by Charles M. Biles History 368: Colonial and Revolutionary America Humboldt State University Spring Semester 2010 Professor Thomas Mays i Introduction The purpose of this paper is to describe the life of William Biles in colonial America. How did William Biles come to leave England and settle on Biles Island? How did William Biles contribute to the political and Quaker development of colonial Pennsylvania? The thesis of this paper is that William Biles was an early English settler who helped develop the political and religious way of life in colonial Pennsylvania. In particular, he helped determine the source of political power: proprietary or popular. Chapter 1 describes how I got interested in history and chose this topic. Chapter 2 describes why William Biles left England and came to America to settle on Biles Island. Chapter 3 describes the key events in the public life of William Biles, especially his activities in Pennsylvania politics and his Quaker ministry. In a certain way, the paper about William Biles was already written by Miles White in 1902.1 White’s 3-part series is the definitive published work on William Biles and details much of his life, including his arrival in America, the highlights of his political career, his activities as a Quaker, and his will. Rather than just writing a biography of this colonial settler, I have placed his life in the background of his times. In particular, I examine his actions and contributions within the forces of the newly developing colony of Pennsylvania. 1 Miles White Jr, “William Biles,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 26, no. -

SPRING 1987 Discover the Secrets of Flemington

J5)untertion Jligtoncal Jletugletter VOL. 23, NO. 2 Published by Hunterdon County Historical Society SPRING 1987 Discover the Secrets of Flemington GUIDE BOOK TO FLEMINGTON, NEW JERSEY SPRING MEETING JUNE 28 FLEMINGTON WOMEN'S CLUB An in-depth guide to Flemington is nearing com• pletion and the co-authors, Barbara Clayton and Kathleen Whitley will be talking with us at the Society's Spring Meeting at 2 p.m. June 28, at the Women's Club on Park Avenue. Their previous guide books were on areas in New England. The latest one will follow a similar format but is about Flemington. It will give the reader histori• cal data about the town and adjacent Raritan Town• ship, explaining the architectural development, and take them on a tour of Flemington via text, maps and photographs. Join us and meet Barbara and Kathleen on • Sunday^the. ?8tb They'll sh^re-with. vnulhp.irp.Ynp.ri- . ences, interesting facts, photographs and anecdotes discovered in their research. Perhaps some of you can answer a question or two they have. • Reading-Large house, 119 Main Street, built ca. 1846 by Mahlon Fisher. A'.. ^„ , '-v The New Jersey Delegation to the Convention County where three generations of his family had played a significant part in the formulation of the resided since the late 1600's. United States Constitution 200 years ago. One of these Did you know New Jersey's Ratification Conven• men was David Brearley, of Hunterdon County. The tion was convened in Hunterdon County? The Fall events leading up to the Convention, what transpired issue will have articles about the Convention at Tren• in Philadelphia two centuries ago during long hot ton in December 1787, and Delegate Joshua Corshon. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (Hereafter, PMHB) 107 (1983), 577-605} See Also Daniel Hoffman, Brotherly Love (New York, 1981)

«*E««««tt«««««**y Jj THE 1* Pennsylvania n Magazine 5 OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY 1* 7%* Peopling and Depeopling of Early Pennsylvania: Indians and Colonists, 1680-1720 ENJAMIN WEST'S FAMOUS PORTRAIT of William Penn treat- ing with the Delaware Indians under the spreading branches B of the elm at Shackamaxon has become an icon of American history. The painting, although inaccurate in its detail, is laden with the symbolism of Christian reconciliation. It depicts the unrealized ideal of the American past: contact between natives and settlers with- out violence, colonization without conquest. West's image of Penn has counterparts in literature, poetry, and history. Penn's "Holy Experi- ment" has been continually depicted as a representation of the possibil- ity, however fleeting, of harmony between the European colonists and the North American Indians.1 For suggestions and encouragement I would like to acknowledge Bernard Bailyn, Rachelle Friedman, Drew R. McCoy, Randall M. Miller, Neal Salisbury, and especially Alden T. Vaughan, who first encouraged my interest in this subject in his seminar a decade ago. 1 On the enduring images of Penn see J. William Frost, <fWilliam Penn's Experiment in the Wilderness: Promise and Legend," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (hereafter, PMHB) 107 (1983), 577-605} see also Daniel Hoffman, Brotherly Love (New York, 1981). Penn's meeting with the Lenape at Shackamaxon has been the subject of dispute for at least 150 years; there is no direct evidence to substantiate the account. See Peter S. Du Ponceau and J. Francis Fisher, A Memoir on the History ojthe Celebrated Treaty Made by William Penn with the Indians under the Elm Tree at Shackamaxon in the Year 1682 (Philadelphia, 1836)j THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY & BIOGRAPHY Vol.