Bottor of ^Fjilosfoptip in HISTORY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transformations of Iran Sufism in the 12Th and 13Th Centuries

Journal of Social Science Studies ISSN 2329-9150 2020, Vol. 7, No. 2 Transformations of Iran Sufism in the 12th and 13th Centuries Seyed Mohammad Hadi Torabi PhD Research Scholar, University of Mysore, India E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 10, 2020 Accepted: March 20, 2020 Published: March 28, 2020 doi: 10.5296/jsss.v7i2.16760 URL: https://doi.org/10.5296/jsss.v7i2.16760 Abstract The 12th and 13th centuries are among the most important periods in the history of Sufism in Iran. During this period, the emergence of many great elders of Sufism and the establishment of the most famous ways and organized dynasty in Sufism by them, the formation of some of the most important treasures of Islamic Sufism, such as the dressing gown and the permission document of the dynasty, the systematic growth and development of the Monasteries as formal institutions and the social status of Sufis and the influence of Sufism in the development of Persian and Arabic prose and poetic, which in this study, briefly, the transformation and effects of Iranian Sufism are examined. Keywords: Cultural equations, Political equations, Religion, Sufism 1. Introduction Iranian Sufism, which has formed in the context of Islamic Sufism and its influence on the Sufism of the ancient religions in Iran, such as Zoroastrianism and Manichaean, has seen tremendous transformations over time, which undoubtedly caused cultural, political, social and even economic changes that have arisen in Iran has led to many ups and downs in the path of growth and excellence. Prior to the 12th century, Sufism continued to exist as a belief system based on knowledge and paths and a mystical view of religion, in which many groups and branches were formed, but differences of them were mostly in the field of thought and had little effect on the space of the community. -

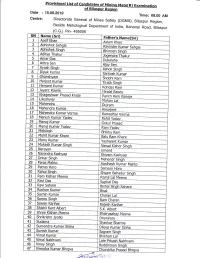

Ffiffi Ffiffiffiffi Ffiffiffi Ffiffiffi

of Bilaspur Reoion Date : 15.06.2019 Time: 08.00 AM Centre: Directorate General of Mines Safety (DGMS), Bitaspur Region, Beside Metrological Department of lndia, Bahatrai Road, Bilaspur (C.G.) pin- 495006 SN I Name (Sri) t--r' 1 I Aasif Khan l-- 2 Abhishek ffi I Sehoia a mbhEhek @ sin6ii--=-- Ehimsen Sinoh 4 l-Aditva rhak;----- ffi 5 I Amar Das --.=--- ffi 6 mritra sen 7 Avush Sinoh ffi B Dipak Kumar ffi 9 Ghanshvam ffi 10 Harjeet Kumar ffi 11 Hemant Kumar r:_- Kffi 12 Javant Rawte ffi 13 Khageshwar Prasad Knoje ffi L4 Likeshwar _----"- ffi 15 Ittahendra uulram ------.------------.--- 16 Mahendra Kurnar -.- -amanEEt 17 ffihenara Kumar Verma ffi 1B Manish Kumar Yadav ffi 19 Manoi Kumar ffi 20 Manoj Kumar Yadav 21 ffi Mithilesh tsniKhu Ram 22 Mohit KumtIhare Balu Ram Khare 23 Monu Kumar Yashwant Kumar 24 Mukesh Kumar Singh Nawal Kishor Singh 25 lNarayan Umend 20 I tttarendra fashyap Shivarn Kashvap 27 I Onkar Sinqh Mahendr Singh Paras 28 I Mahto Awdhesh Kumar Mahto 29 I Patros Horo Samson Horo 30 I Rahul Sinsh Shvam BahtiLtr Sinqh* 31 Ram Kishan Meena Ramji Lal Meena 32 I Ravi Das Suphal Das 33 Ravi Sahare Bishal Singh Sahare 34 Roshan Kumar Bisal 35 Sachin Kumar Charan Lal --.- 36 Samru Singh Ram Charan 37 Sawan Karihar Rajesh Karihar ?o Shishil Kant Albert S.K. Albert 39 Shree Kishan Meena Bhairusahav Meena 40 Shrikrishn Jyotki Dhaniram. 4L Sudama Shankar Sharma 42 Sumendra Kumar Sinha Dilaep Kumar Sinht- 43 Suresh Kumar Saqram Sinoh 44 Vimal Kumar Bhikhari Lal 45 Vimal Nabhvani Late Prkash Nabhvani 46 Vinay Singh Buddhiman Singh 47 Virendra -

Energy Trade in South Asia Opportunities and Challenges

Energy Trade in South Asia in South Asia: Energy Trade Opportunities and Challenges The South Asia Regional Energy Study was completed as an important component of the regional technical assistance project Preparing the Energy Sector Dialogue and South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation Energy Center Capacity Development. It involved examining regional energy trade opportunities among all the member states of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation. The study provides interventions to improve regional energy cooperation in different timescales, including specific infrastructure projects which can be implemented during Opportunities and Challenges these periods. ENERGY TRADE IN SOUTH ASIA About the Asian Development Bank OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.8 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 903 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. Sultan Hafeez Rahman Priyantha D. C. Wijayatunga Herath Gunatilake P. N. Fernando Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org Printed on recycled paper. Printed in the Philippines ENERGY TRADE IN SOUTH ASIA OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES Sultan Hafeez Rahman Priyantha D. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

App for Downloading Older Songs App for Downloading Older Songs

app for downloading older songs App for downloading older songs. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66aa3d60eb3084bc • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. , Old Hindi Songs MP3 Music App. Old Hindi Songs is a music App that has been especially created for Bollywood music fans who love listening to Old Hindi Music. Download Old Hindi Songs, Unlimited MP3 Music & Old Hindi Classics. The app has the largest collection of Purane gane in wide genres like - Romantic Old Songs, Sad Songs, Retro Classics, Ghazals etc. Find all your favourite Retro singers’ songs: Mohammad Rafi, Lata Mangeshkar, Manna Dey, Kishore Kumar, Asha Bhosle, S.D. Burman, Mahendra Kapoor, Mukesh, Talat Mahmood, Geeta Dutt, Hemant Kumar, Shamshad Begum, Jagjit Singh. O.P. Nayyar, Naushad, Madan Mohan, Khayyam, Shankar Jaikishan, Laxmikant Pyarelal, Kalyanji Anand, Salil Choudhury, Roshan. You can search for your favourite Old songs or play music from thousands of playlists created by Gaana editorial experts. -

List of Entries

List of Entries A Ahmad Raza Khan Barelvi 9th Month of Lunar Calendar Aḥmadābād ‘Abd al-Qadir Bada’uni Ahmedabad ‘Abd’l-RaḥīmKhān-i-Khānān Aibak (Aybeg), Quṭb al-Dīn Abd al-Rahim Aibek Abdul Aleem Akbar Abdul Qadir Badauni Akbar I Abdur Rahim Akbar the Great Abdurrahim Al Hidaya Abū al-Faḍl ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Ḥusayn (Ghūrid) Abū al-Faḍl ‘Allāmī ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Khaljī Abū al-Faḍl al-Bayhaqī ʿAlāʾ al-DīnMuḥammad Shāh Khaljī Abū al-Faḍl ibn Mubarak ‘Alā’ ud-Dīn Ḥusain Abu al-Fath Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar ʿAlāʾ ud-Dīn Khiljī Abū al-KalāmAzād AlBeruni Abū al-Mughīth al-Ḥusayn ibn Manṣūr al-Ḥallāj Al-Beruni Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar al-Suhrawardī AlBiruni Abu’l Fazl Al-Biruni Abu’l Fazl ‘Allāmī Alfī Movements Abu’l Fazl ibn Mubarak al-Hojvīrī Abū’l Kalām Āzād Al-Huda International Abū’l-Fażl Bayhaqī Al-Huda International Institute of Islamic Educa- Abul Kalam tion for Women Abul Kalam Azad al-Hujwīrī Accusing Nafs (Nafs-e Lawwāma) ʿAlī Garshāsp Adaran Āl-i Sebüktegīn Afghan Claimants of Israelite Descent Āl-i Shansab Aga Khan Aliah Madrasah Aga Khan Development Network Aliah University Aga Khan Foundation Aligarh Muslim University Aga Khanis Aligarh Muslim University, AMU Agyaris Allama Ahl al-Malāmat Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-Mashriqi Aḥmad Khān Allama Mashraqi Ahmad Raza Khan Allama Mashraqui # Springer Science+Business Media B.V., part of Springer Nature 2018 827 Z. R. Kassam et al. (eds.), Islam, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism, Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1267-3 828 List of Entries Allama Mashriqi Bangladesh Jamaati-e-Islam Allama Shibili Nu’mani Baranī, Żiyāʾ al-Dīn Allāmah Naqqan Barelvīs Allamah Sir Muhammad Iqbal Barelwīs Almaniyya BāyazīdAnṣārī (Pīr-i Rōshan) Almsgiving Bāyezīd al-Qannawjī,Muḥammad Ṣiddīq Ḥasan Bayhaqī,Abūl-Fażl Altaf Hussain Hali Bāzīd Al-Tawḥīd Bedil Amīr ‘Alī Bene Israel Amīr Khusrau Benei Manasseh Amir Khusraw Bengal (Islam and Muslims) Anglo-Mohammedan Law Bhutto, Benazir ʿAqīqa Bhutto, Zulfikar Ali Arezu Bīdel Arkān al-I¯mān Bidil Arzu Bilgrāmī, Āzād Ārzū, Sirāj al-Dīn ‘Alī Ḳhān (d. -

Critical Discourse Analysis of Marsiya-E-Hussain

Religious Ideology and Discourse: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Marsiya-e-Hussain Snobra Rizwan Lecturer, Department of English Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan Pakistan Tariq Saeed Assisstant Professor, Department of English Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan Pakistan Ramna Fayyaz Lecturer, Department of English Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan Pakistan ABSTRACT This paper employs Fairclough’s framework of critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, 2001; 2003) as a research tool to demonstrate how mourning discourse of marsiya manages to win favourite responses from Pakistani audiences by foregrounding certain linguistic conventions. The data comprising popular marsiyas are based on responses obtained through a small-scale survey and are analyzed from the perspective of ideology and emotive appeal embedded in discourse. The analysis illustrates that discourse conventions of marsiya—in addition to traditional commemoration of martyrdom of Imam Hussian—serve to elaborate, explain and disseminate religious doctrines in Pakistani Shi‘ah masses. Keywords: Marsiya, Critical Discourse Analysis, Ideology, Shiism 1. Introduction This paper provides a close study to examine the distinguishing features of marsiya-e-Hussain and the way discursive choices of certain transitivity features, figurative language and lyrical conventions serve to make it a distinct poetic genre of its own. Though marsiya recitation is taken to be a means of commemorating the martyrdom of Imam Hussain; nevertheless, it means much more to Shi’ia community. Along with other mourning rituals, marsiya is considered to be a means of seeking waseela (mediation) from the saints, teaching and learning religious ideologies, seeking God’s pleasure and so on (‘Azadari; mourning for Imam Hussain’, 2009). All these objectives are achieved by following certain discourse conventions which in turn construct certain discursive reality and weigh heavily on the formation of distinctive opinion and religious ideology in Shi‘ah masses. -

Boctor of $F)Ilos(Op})P I Jn M I I

SUFI THOUGHT OF MUHIBBULLAH ALLAHABADI Abstract Thesis SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of $f)ilos(op})p I Jn M I I MOHD. JAVED ANS^J. t^ Under the Supervision of Prof. MUHAMMAD YASIN MAZHAR SIDDiQUi DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2006 Abstract The seventeenth Century of Christian era occupies a unique place in the history of Indian mystical thought. It saw the two metaphysical concepts Wahdat-al Wujud (Unity of Being) and Wahdat-al Shuhud (Unity of manifestation) in the realm of Muslim theosophy and his conflict expressed itself in the formation of many religious groups, Zawiyas and Sufi orders on mystical and theosophical themes, brochures, treatises, poems, letters and general casuistically literature. The supporters of these two schools of thought were drawn from different strata of society. Sheikh Muhibbullah of Allahabad, Miyan Mir, Dara Shikoh, and Sarmad belonged to the Wahdat-al Wujud school of thought; Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi, Khawaja Muhammad Masum and Gulam Yahya belonged to the other school. Shaikh Abdul Haqq Muhaddith and Shaikh WalliuUah, both of Delhi sought to steer a middle course and strove to reconcile the conflicting opinions of the two schools. Shaikh Muhibbullah of Allahabad stands head and shoulder above all the persons who wrote in favour of Wahdat-al Wujud during this period. His coherent and systematic exposition of the intricate ideas of Wahdat- al Wujud won for him the appellation of Ibn-i-Arabi Thani (the second Ibn-i Arabi). Shaikh Muhibbullah AUahabadi was a prolific writer and a Sufi of high rapture of the 17* century. -

İmam-I Rabbani Sempozyumu Tebliğleri AZÎZ MAHMÛD HÜDÂYİ VAKFI YAYINLARI No : 03

Uluslararası İmam-ı Rabbani Sempozyumu Tebliğleri AZÎZ MAHMÛD HÜDÂYİ VAKFI YAYINLARI No : 03 Editör Prof. Dr. Necdet TOSUN Sekreterya Furkan MEHMED Grafik&Tasarım Ahmet DUMAN Baskı İstanbul - 2018 ISBN 978-605-68070-2-2 "Azîz Mahmûd Hüdâyi Vakfı Yayınları" "Azîz Mahmûd Hüdâyi Vakfı İktisadi İşletmesi"ne aittir. İletişim: Aziz Mahmûd Hüdâyi Vakfı İktisadi İşletmesi Küçükçamlıca Mah. Duhancı Mehmet Sok. No: 33/1 Posta Kodu: 34696 Üsküdar / İstanbul Tel: 0216 428 39 60 Faks: 0 216 339 47 52 Shaikh Mujaddid-i Alf-i Sani: A Survey of Works in India Tayyeb Sajjad Asghar1 The Naqshbandi silsilah occupies an important place in the annals of Islam in Indian sub-continent. For nearly two centuries, i.e. 17th & 18th, it was the principal spiritual order in India and its influence permeated far and deep into Indo-Mus- lim life. Though many Naqshbandi saints came to India and associated themselves with the royal courts of Emperor Babur, Humayun and Akbar. The credit of really organizing and propagating the Naqshbandi silsila in this country goes to Khwaja Muhammad Baqi Billah, who came to India from Kabul, his native town, and his disciple, khalifa and the chief successor Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi known as “Mujad- did-i Alf-i Sani. He played most important role in disseminating the ideology and practices of the Naqshbandi silsilah in India. He was the first Muslim Sufi scholar of the Indian sub-continent whose thought and movement reached far beyond the Indian frontiers and influenced Muslim scholars and saints in different regions. His spiritual descendants (khalifas) zealously participated in the organization of the “Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi” silsilah in India, Afghanistan, Central Asia, Turkey, Arabia, Egypt, Morocco and Indonesia. -

Varieties of South Asian Islam Francis Robinson Research Paper No.8

Varieties of South Asian Islam Francis Robinson Research Paper No.8 Centre for Research September 1988 in Ethnic Relations University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7Al Francis Robinson is a Reader in History at the Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, University of London. For the past twenty years he has worked on Muslim politics and Islamic institutions in South Asia and is the author of many articles relating to these fields. His main books are: Separatism Among Indian Muslims: The Politics of the United Provinces' Muslims 1860-1923 (Cambridge, 1974); Atlas of the Islamic World since 1500 (Oxford, 1982); Islam in Modern South Asia (Cambridge, forthcoming); Islamic leadership in South Asia: The 'Ulama of Farangi Mahall from the seventeenth to the twentieth century (Cambridge, forthcoming). Varieties of South Asian Islam1 Over the past forty years Islamic movements and groups of South Asian origin have come to be established in Britain. They offer different ways, although not always markedly different ways, of being Muslim. Their relationships with each other are often extremely abrasive. Moreover, they can have significantly different attitudes to the state, in particular the non-Muslim state. An understanding of the origins and Islamic orientations of these movements and groups would seem to be of value in trying to make sense of their behaviour in British society. This paper will examine the following movements: the Deobandi, the Barelvi, the Ahl-i Hadith, the Tablighi Jamaat, the Jamaat-i Islami, the Ahmadiyya, and one which is unlikely to be distinguished in Britain by any particular name, but which represents a very important Islamic orientation, which we shall term the Modernist.2 It will also examine the following groups: Shias and Ismailis. -

Orix Leasing Pakistan Limited List of Shareholders Without Cnic As on October 21, 2016

ORIX LEASING PAKISTAN LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WITHOUT CNIC AS ON OCTOBER 21, 2016 NO. OF S. NO FOLIO NO. NAME FATHER'S \ HUSBAND'S NAME ADDRESS SHARES 5/20, DR. DATOO MANZIL, AGA KHAN ROAD 1 14 MOHAMMED MOOSA S/O MOHAMMED HUSSAIN 102 KHARADAR, KARACHI. M.R.6/13, VIRJEE STREET, JODIA BAZAR, 2 62 SH. AFZAL HUSSAIN S/O MOHD IQBAL 109 KARACHI. B-116, NEW DHORAJI COLONY, GULSHAN-E- 3 64 KHAIRUN BAI W/O MOHD IQBAL 98 IQBAL, BLOCK-4, KARACHI-47. 8, SHAH MOHD BUILDING, KIMAT RAI BHOJ 4 69 MOHD AMIN BHIMANI S/O ABDUL GHAFFAR BHIMANI 27 RAJ ROAD, ARAM BAGH, KARACHI. B-110, BLOCK-I, NORTH NAZIMABAD, 5 76 SAIFULLAH KHARI S/O MD ISHRATULLAH 658 KARACHI. C-42, BLOCK A , NORTH NAZIMABAD, 6 107 HADISUN NISA BEGUM W/O MOHAMMAD MASSOD KHAN 2,042 KARACHI. BROADWAY APPARTMENT, 2ND FLOOR FLAT 7 159 FATIMA W/O HAJI WALI MOHAMMED B-2, C-2, PLOT NO.227, STREET-16, B.M.C.H. 138 SOCIETY, SHARFABAD, KARACHI-74800. D.V. 71, USMANIA COLONY, B. ROAD, 8 340 MOHD HANIF S/O KHUDA BAKASH 138 NAZIMABAD NO.1, KARACHI. A/19-1, KHUDAD COLONY, KASHMIR ROAD, 9 344 M. A. RAOOF BAIG S/O M. REHMAT BAIG 169 KARACHI-5. 153 JINNAH COLINY MUSLIM ROAD, 10 524 TANVEER MEHRAJ S/O MEHRAJ DIN 35 SAMANABAD, LAHORE. C/O KHAWAJA TARIQ MAHMOOD, 18/B, TECH 11 525 FARZANA JABEEN D/O KH. BASHIRUDDIN 936 SOCIETY, CANAL BANK, LAHORE. HOUSE NO.18, STREET NO.35, SECTOR I-9/4, 12 526 MAHMUD AHMED S/O RIAZ AHMED 304 ISLAMABAD. -

Produced by the Human Security Centre Lead Author

1 Human Security Centre – Written evidence (AFG0019) Produced by the Human Security Centre Lead Author: Simon Schofield, Senior Fellow, In consultation with Rohullah Yakobi, Associate Fellow 2 1 Table of Contents 2. Executive Summary .............................................................................5 3. What is the Human Security Centre?.....................................................10 4. Geopolitics and National Interests and Agendas......................................11 Islamic Republic of Pakistan ...................................................................11 Historical Context...............................................................................11 Pakistan’s Strategy.............................................................................12 Support for the Taliban .......................................................................13 Afghanistan as a terrorist training camp ................................................16 Role of military aid .............................................................................17 Economic interests .............................................................................19 Conclusion – Pakistan .........................................................................19 Islamic Republic of Iran .........................................................................20 Historical context ...............................................................................20 Iranian Strategy ................................................................................23