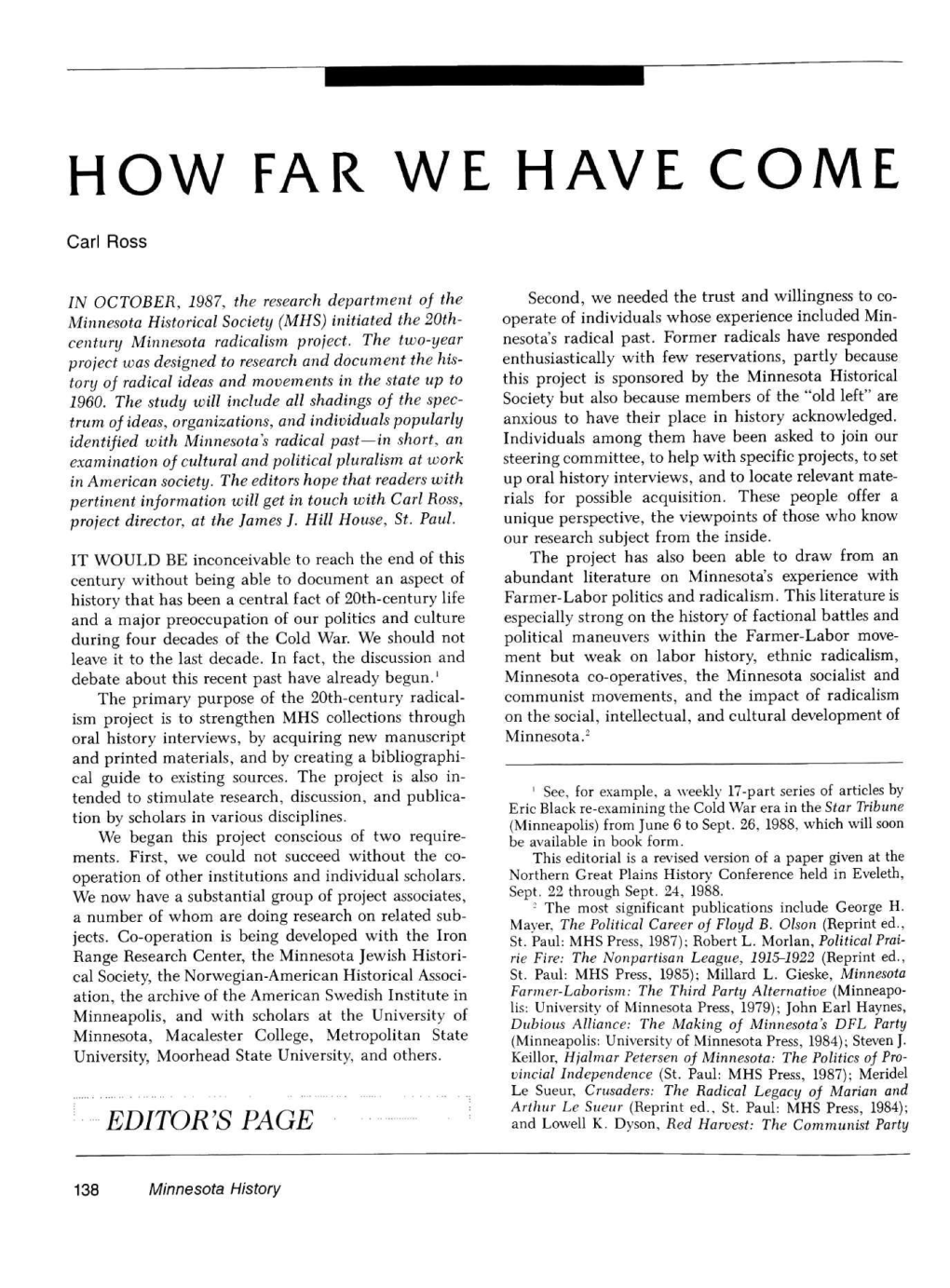

A Report on the 20Th-Century Radicalism in Minnesota Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting the Challenge of Crisis and Opportunity Left Refoundation and Party Building

Meeting the Challenge of Crisis and Opportunity Left Refoundation and Party Building About this paper: The Party-Building Commission The slogan of Left Refoundation arises out of our of Freedom Road Socialist Organization takes assessment of the ideological and structural crisis pleasure in circulating the following paper. Like among Leftists here in the U.S. and other parts of other socialist organizations, since its inception, the world. Four major occurrences define this crisis: Freedom Road has looked for opportunities to com- (1) The crisis of socialism, which predates the bine our own organizing with opportunities for collapse of the Soviet Union strengthening the unity and coherence of socialist efforts overall. We endorse the themes presented (2) The dismantling of the welfare state, here as an important part of our efforts in this gen- (3) The crisis of national liberation movements, eral direction. Members of our organization from and several cities worked on this paper over the last year and a half. We also appreciate the invaluable (4) The rise of neoliberalism. comments of friends and co-workers from other or- All four are connected. The rise of neoliberalism and ganizations who have seen this in draft and helped the crisis of socialism are intertwined with the de- shape it. We don't see this as the final word on the struction of the welfare state and the crisis of na- way forward for the socialist left. Nor do we even tional liberation movements. This crisis is an ideo- see it as the first word, since others have also grap- logical and structural vacuum in which words such pled with similar issues throughout this past decade. -

China's Communist Party Absorbs More of the State

March 23, 2018 China’s Communist Party Absorbs More of the State In March 2018, China’s national legislature, the National usual two terms. Xi’s second term in his Party posts is People’s Congress (NPC), approved amendments to scheduled to end in 2022, and his second term as president China’s state constitution, including the elimination of term is scheduled to end in March 2023. limits for the positions of President and Vice President. The NPC also supported the creation of a new anti-graft agency, Many analysts warn that by undermining China’s efforts to approved a reorganization of government agencies, create norms around the orderly transfer of power, the installed a new lineup of state and NPC leaders, and removal of term limits could increase the risk of a future endorsed economic and other targets. On March 21, 2018, destabilizing succession crisis in the world’s second-largest immediately after the NPC session closed, the Communist economy. Some U.S. observers have expressed cautious Party released a document outlining a broad re-organization hope that with the prospect of staying in power indefinitely, of large parts of China’s political system, including the President Xi may feel he has a freer hand to pursue needed Party. The events served to strengthen the position of economic reforms. Others have expressed concern that Xi Communist Party General Secretary and State President Xi could pursue an even more assertive foreign policy. Jinping, to expand the Communist Party of China’s already dominant role in China’s political life, and to give the Party Strengthening the Constitutional Basis for more tools to pursue its nationalist agenda. -

USA and RADICAL ORGANIZATIONS, 1953-1960 FBI Reports from the Eisenhower Library

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Research Collections in American Radicalism General Editors: Mark Naison and Maurice Isserman THE COMMUNIST PARTY USA AND RADICAL ORGANIZATIONS, 1953-1960 FBI Reports from the Eisenhower Library UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Research Collections in American Radicalism General Editors: Mark Naison and Maurice Isserman THE COMMUNIST PARTY, USA, AND RADICAL ORGANIZATIONS, 1953-1960 FBI Reports from the Eisenhower Library Project Coordinator and Guide Compiled by Robert E. Lester A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Communist Party, USA, and radical organizations, 1953-1960 [microform]: FBI reports from the Eisenhower Library / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels. - (Research collections in American radicalism) Accompanied by printed reel guide compiled by Robert E. Lester. ISBN 1-55655-195-9 (microfilm) 1. Communism-United States--History--Sources--Bibltography-- Microform catalogs. 2. Communist Party of the United States of America~History~Sources~Bibliography~Microform catalogs. 3. Radicalism-United States-History-Sources-Bibliography-- Microform catalogs. 4. United States-Politics and government-1953-1961 -Sources-Bibliography-Microform catalogs. 5. Microforms-Catalogs. I. Lester, Robert. II. Communist Party of the United States of America. III. United States. Federal Bureau of Investigation. IV. Series. [HX83] 324.27375~dc20 92-14064 CIP The documents reproduced in this publication are among the records of the White House Office, Office of the Special Assistant for National Security Affairs in the custody of the Eisenhower Library, National Archives and Records Administration. -

File Is Composed of the Comfortable Class

The English Radical Tradition and the British Left 1885-1945 ENDERBY, John Stephen Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26096/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26096/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. The English Radical Tradition and the British Left 1885-1945 by John Stephen Enderby A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 I hereby declare that: 1. I have not been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University's policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acknowledged. 4. The work undertaken towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy. -

Greenpeace, Earth First! and the Earth Liberation Front: the Rp Ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008)

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2008 Greenpeace, Earth First! and The aE rth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher J. Covill University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Covill, Christopher J., "Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 93. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The Progression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher John Covill Faculty Sponsor: Professor Timothy Hennessey, Political Science Causes of worldwide environmental destruction created a form of activism, Ecotage with an incredible success rate. Ecotage uses direct action, or monkey wrenching, to prevent environmental destruction. Mainstream conservation efforts were viewed by many environmentalists as having failed from compromise inspiring the birth of radicalized groups. This eventually transformed conservationists into radicals. Green Peace inspired radical environmentalism by civil disobedience, media campaigns and direct action tactics, but remained mainstream. Earth First’s! philosophy is based on a no compromise approach. -

PROOF Contents

PROOF Contents Acknowledgements viii 1 Survival and Renewal: The 1990s 1 2 Regroupment: Establishing a European Movement 29 3 The Party of the European Left 46 4 Diverse Trends: An Overview 66 5 A Successful Model? Die Linke (the Left Party – Germany) 83 6 How Have the Mighty Fallen: Partito della Rifondazione Comunista (Party of Communist Refoundation – Italy) 99 7 Back from the Brink: French Communism (Parti Communiste Français) Re-orientates 116 8 Communism Renewed and Supported: The Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (the Czech Republic) 132 9 The Scandinavian Left 147 10 The European Left and the Global Left: 1999–2009 163 Notes 192 Index 204 vii PROOF 1 Survival and Renewal: The 1990s Almost two decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, on the occasion of the German federal elections in September 2009, the International Herald Tribune marked the electoral victory of the German right with the headline, ‘Is socialism dying?’1 The German Social Democratic Party or the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) took 23% of the votes – its lowest poll since the Second World War – just months after the European elections registered a poor performance from left- wing candidates across the European Union (EU). As the article went on to observe, ‘Even in the midst of one of the greatest challenges to capitalism in 75 years, involving a breakdown of the financial sys- tem because of “irrational exuberance”, greed and the weakness of regulatory systems, European socialists and their leftist cousins have not found a compelling response, let alone taken advantage of the failures of the right.’ There is no doubt that across Europe the failure of the social demo- cratic parties to present a ‘compelling response’ to the economic crisis has led to a wave of electoral setbacks. -

TRANSNATIONAL PARTY ACTIVITY and PORTUGAL's RELATIONS with the EUROPEAN COMMUNITY

TRANSNATIONAL PARTY ACTIVITY and PORTUGAL'S RELATIONS WITH THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Juliet Antunes Sablosky Georgetown University Paper Prepared for Delivery at the Fourth Biennial International Conference of The European Community Studies Association May 11-14, 1995 Charleston, South Carolina This paper analyzes the interaction of the domestic and international systems during Portugal's transition to democracy in the 1970's. It focuses on the role which the European Community played in the process of democratization there, using transnational party activity as a prism through which to study the complex set of domestic and international variables at work in that process. The paper responds to the growing interest in the role of the European Community as a political actor, particularly in its efforts to support democratization in aspiring member states. The Portuguese case, one of the first in which the EC played such a role, offers new insights into how EC related party activity can affect policy-making at national and international levels. The case study centers on the Portuguese Socialist Party (PS) and its relationship with the socialist parties1 in EC member states, with the Confederation of the Socialist Parties of the European Community and the Socialist Group in the European Parliament. Its central thesis is that transnational party activity affected not only EC policy making in regard to Portugal, but had demonstrable effects on the domestic political system as well. Using both interdependence and linkages theory as its base, the paper builds on earlier work by Geoffrey Pridham (1990, 1991), Laurence Whitehead (1986, 1991) and others, on the EC's role in democratization in Southern Europe. -

A History of Modern Palestine

A HISTORY OF MODERN PALESTINE Ilan Pappe’s history of modern Palestine has been updated to include the dramatic events of the s and the early twenty-first century. These years, which began with a sense of optimism, as the Oslo peace accord was being negotiated, culminated in the second intifada and the increase of militancy on both sides. Pappe explains the reasons for the failure of Oslo and the two-state solution, and reflects upon life thereafter as the Palestinians and Israelis battle it out under the shadow of the wall of separation. I P is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Haifa in Israel. He has written extensively on the politics of the Middle East, and is well known for his revisionist interpretation of Israel’s history. His books include The Making of the Arab–Israeli Conflict, – (/) and The Modern Middle East (). A HISTORY OF MODERN PALESTINE One Land, Two Peoples ILAN PAPPE University of Haifa, Israel CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521683159 © Ilan Pappe 2004, 2006 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Second edition 2006 7th printing 2013 Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by the MPG Books Group A catalog record for this publication is available from the British Library. -

The Evolution of Radical Rhetoric: Radical Baby Boomer

THE EVOLUTION OF RADICAL RHETORIC: RADICAL BABY BOOMER DISCOURSE ON FACEBOOK IN THE 21ST CENTURY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY EDWIN FAUNCE ADVISOR: JAMES W. CHESEBRO BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2012 2 Table of Contents Title Page 1 Table of Contents 2 Dedication 3 Acknowledgement 4 Chapter 1: The Problem 5 Chapter 2: LiteratUre Review 11 Chapter 3: Method 24 Chapter 4: Boomer Profile Analysis ConclUsions 47 Chapter 5: Final ConclUsions, Limitations, and Recommendations 58 Works Cited 68 Appendix 74 3 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my children, Rachel and Abigail, with my loVe and admiration. 4 ACknowledgements First and foremost I want to thank and acknowledge my adVisor, and committee chair James W. Chesebro Ph.D. for his gUidance, and extreme hard work coaching and helping me figUre oUt what was in my head. Next, I want to also thank my committee members. I want to thank Michael Holmes Ph.D. for his continued thoughtful and incisive input to this thesis from when it was just an idea rUminating in my head Up to the work that you see before you. I want to thank Melinda Messineo Ph.D. for her encoUragement and help to focus on my topic while I was assembling this thesis proposal. Thank yoU all for yoUr stellar work on this thesis committee. I would like to acknowledge Michael Gerhard Ph.D. for his direction and encoUragement, and also thank the rest of my master’s cohort for listening to the many pedantic papers and lectUres they had to endUre on the sUbject of the elderly on Facebook. -

5195E05d4.Pdf

ILGA-Europe in brief ILGA-Europe is the European Region of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans & Intersex Association. ILGA-Europe works for equality and human rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans & intersex (LGBTI) people at European level. ILGA-Europe is an international non-governmental umbrella organisation bringing together 408 organisations from 45 out of 49 European countries. ILGA-Europe was established as a separate region of ILGA and an independent legal entity in 1996. ILGA was established in 1978. ILGA-Europe advocates for human rights and equality for LGBTI people at European level organisations such as the European Union (EU), the Council of Europe (CoE) and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). ILGA-Europe strengthens the European LGBTI movement by providing trainings and support to its member organisations and other LGBTI groups on advocacy, fundraising, organisational development and communications. ILGA-Europe has its office in Brussels and employs 12 people. Since 1997 ILGA-Europe enjoys participative status at the Council of Europe. Since 2001 ILGA-Europe receives its largest funding from the European Commission. Since 2006 ILGA-Europe enjoys consultative status at the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (ECOSOC) and advocates for equality and human rights of LGBTI people also at the UN level. ILGA-Europe Annual Review of the Human Rights Situation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex People in Europe 2013 This Review covers the period of January -

Minnesota's Scandinavian Political Legacy

Minnesota’s Scandinavian Political Legacy by Klas Bergman In 1892, Minnesota politics changed, for good. In that break-through year, Norwegian-born, Knute Nelson was elected governor of Minnesota, launching a new era with immigrants and their descendants from the five Nordic countries in leadership positions, forming a new political elite that has reshaped the state’s politics. The political story of the Scandinavian immigrants in Minnesota is unique. No other state can show a similar political involvement, although there are examples of Scandinavian political leaders in other states. “Outside of the Nordic countries, no other part of the world has been so influenced by Scandinavian activities and ambitions as Minnesota,” Uppsala University professor Sten Carlsson once wrote.1 Their imprint has made Minnesota the most Scandinavian of all the states, including in politics. These Scandinavian, or Nordic, immigrants from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden created a remarkable Scandinavian political legacy that has shaped Minnesota politics in a profound way and made it different from other states, while also influencing American politics beyond Minnesota. Since 1892, the Scandinavians and their descendants have been at the forefront of every phase of Minnesota’s political history. All but five of Minnesota’s twenty-six governors during the following 100 years have been Scandinavians—mostly Swedes and Norwegians, but also a Finland-Swede and a Dane, representing all political parties, although most of them— twelve—were Republicans. Two of them were talked about as possible candidates for the highest office in the land, but died young—John Governor Knute Nelson. Vesterheim Archives. -

Dataset of Electoral Volatility in the European Parliament Elections Since 1979 Codebook (July 31, 2019)

Dataset of Electoral Volatility in the European Parliament elections since 1979 Vincenzo Emanuele (Luiss), Davide Angelucci (Luiss), Bruno Marino (Unitelma Sapienza), Leonardo Puleo (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna), Federico Vegetti (University of Milan) Codebook (July 31, 2019) Description This dataset provides data on electoral volatility and its internal components in the elections for the European Parliament (EP) in all European Union (EU) countries since 1979 or the date of their accession to the Union. It also provides data about electoral volatility for both the class bloc and the demarcation bloc. This dataset will be regularly updated so as to include the next rounds of the European Parliament elections. Content Country: country where the EP election is held (in alphabetical order) Election_year: year in which the election is held Election_date: exact date of the election RegV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between parties that enter or exit from the party system. A party is considered as entering the party system where it receives at least 1% of the national share in election at time t+1 (while it received less than 1% in election at time t). Conversely, a party is considered as exiting the part system where it receives less than 1% in election at time t+1 (while it received at least 1% in election at time t). AltV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between existing parties, namely parties receiving at least 1% of the national share in both elections under scrutiny. OthV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between parties falling below 1% of the national share in both the elections at time t and t+1.