International Law and the Sharing of Pathogens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defining Health Diplomacy: Changing Demands in the Era of Globalization

THE MILBANK QUARTERLY A MULTIDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL OF POPULATION HEALTH AND HEALTH POLICY Defining Health Diplomacy: Changing Demands in the Era of Globalization REBECCA KATZ, SARAH KORNBLET, GRACEARNOLD,ERICLIEF, and JULIE E. FISCHER George Washington University; Stimson Global Health Security Program Context: Accelerated globalization has produced obvious changes in diplomatic purposes and practices. Health issues have become increasingly preeminent in the evolving global diplomacy agenda. More leaders in academia and policy are thinking about how to structure and utilize diplomacy in pursuit of global health goals. Methods: In this article, we describe the context, practice, and components of global health diplomacy, as applied operationally. We examine the foundations of various approaches to global health diplomacy, along with their implications for the policies shaping the international public health and foreign policy environments. Based on these observations, we propose a taxonomy for the subdiscipline. Findings: Expanding demands on global health diplomacy require a delicate combination of technical expertise, legal knowledge, and diplomatic skills that have not been systematically cultivated among either foreign service or global health professionals. Nonetheless, high expectations that global health initia- tives will achieve development and diplomatic goals beyond the immediate technical objectives may be thwarted by this gap. Conclusions: The deepening links between health and foreign policy require both the diplomatic and global health communities to reexamine the skills, comprehension, and resources necessary to achieve their mutual objectives. Keywords: Global health, diplomacy, foreign policy. Address correspondence to: Sarah Kornblet, Stimson Global Health Security Program, 12th Floor, 1111 19th St. NW, Washington, DC 20036 (email: [email protected]). The Milbank Quarterly, Vol. -

(2005) Through Cooperative Bioengagement

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 13 October 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00231 Implementation of the International Health Regulations (2005) through cooperative bioengagement Claire J. Standley , Erin M. Sorrell , Sarah Kornblet , Julie E. Fischer and Rebecca Katz* Global Health Security Program, Department of Health Policy and Management, Milken Institute School of Public Health, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA Cooperative bioengagement efforts, as practiced by U.S. government-funded entities, such as the Defense Threat Reduction Agency’s Cooperative Biological Engagement Program, the State Department’s Biosecurity Engagement Program, and parallel pro- grams in other countries, exist at the nexus between public health and security. These programs have an explicit emphasis on developing projects that address the priorities of the partner country as well as the donor. While the objectives of cooperative bioengage- ment programs focus on reducing the potential for accidental or intentional misuse and/ or release of dangerous biological agents, many partner countries are interested in bio- engagement as a means to improve basic public health capacities. This article examines the extent to which cooperative bioengagement projects address public health capacity Edited by: Nathan Wolfe, building under the revised International Health Regulations and alignment with the Global Metabiota, USA Health Security Agenda action packages. Reviewed by: Keywords: International Health Regulations, Global Health Security Agenda, biological -

Can an Attribution Assessment Be Made for Yellow Rain? Systematic Reanalysis in a Chemical-And-Biological-Weapons Use Investigation

Can an attribution assessment be made for Yellow Rain? Systematic reanalysis in a chemical-and-biological-weapons use investigation Rebecca Katz, Ph.D.* Department of Health Policy George Washington University 2021 K Street, NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20006 [email protected] * Corresponding author. Burton Singer, Ph.D. Office of Population Research 245 Wallace Hall Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544 [email protected] ABSTRACT. In intelligence investigations, such as those into reports of chemical- or biological-weapons (CBW) use, evidence may be difficult to assemble and, once assembled, to weigh. We propose a methodology for such investigations and then apply it to a large body of recently declassified evidence to determine the extent to which an attribution can now be made in the Yellow Rain case. Our analysis strongly supports the hypothesis that CBW were used in Southeast Asia and Afghanistan in the late 1970s and early 1980s, although a definitive judgment cannot be made. The proposed methodology, while resource-intensive, allows evidence to be assembled and analyzed in a transparent manner so that assumptions and rationale for decisions can be challenged by external critics. We conclude with a discussion of future research directions, emphasizing the use of evolving information-extraction (IE) technologies, a sub-field of artificial intelligence (AI). here is a science to the collection of evidence in ences from single, novel events. Standards of evidence an intelligence investigation. Experienced ana- and inference are ill-defined -

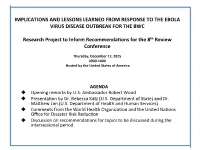

Implications and Lessons Learned from Response to the Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak for the Bwc

IMPLICATIONS AND LESSONS LEARNED FROM RESPONSE TO THE EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE OUTBREAK FOR THE BWC Research Project to Inform RecommendaCons for the 8th Review Conference Thursday, December 17, 2015 0900-1000 Hosted by the United States of America AGENDA u Opening remarks by U.S. Ambassador Robert Wood u Presentaon by Dr. Rebecca Katz (U.S. Department of State) and Dr. Mahew Lim (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) u Comments from the World Health Organizaon and the United Naons Office for Disaster Risk Reduc9on u Discussion on recommendaons for topics to be discussed during the intersessional period. IMPLICATIONS AND LESSONS LEARNED FROM RESPONSE TO THE EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE OUTBREAK FOR THE BIOLOGICAL WEAPONS CONVENTION Research Project to Inform RecommendaCons for the 8th Review Conference Rebecca Katz, PhD MPH U.S. Department of State [email protected] Mahew Lim, MD U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [email protected] Objecves • Project background • About the project – Methodology – Interview Ques9ons • Preliminary findings • How findings fit within larger reform context Ebola Response & the BWC • Response to Ebola in West Africa has fundamentally challenged preconcep9ons about internaonal assistance following a public health emergency, straining global public health emergency response and necessitang sustained contribu9ons from: • Naonal Governments • Intergovernmental Organizaons • Internaonal Organizaons: and • Charitable Organizaons, Foundaons, and Individual Donors. Ebola Response & the BWC BWC States Par9es recommendaons to assess Ebola response for lessons relevant to Ar9cle VII of the Conven9on. About Our Project Intent: to learn from NGOs, IOS and bilateral donors how response to Ebola outbreak might have been different if there had been a deliberate component. -

Managing Dangerous Pathogens: Challenges in the Wake of the Recent West African Ebola Outbreak

Global Security: Health, Science and Policy An Open Access Journal ISSN: (Print) 2377-9497 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rgsh20 Managing dangerous pathogens: challenges in the wake of the recent West African Ebola outbreak Akin Abayomi, Rebecca Katz, Scott Spence, Brian Conton & Sahr M. Gevao To cite this article: Akin Abayomi, Rebecca Katz, Scott Spence, Brian Conton & Sahr M. Gevao (2016): Managing dangerous pathogens: challenges in the wake of the recent West African Ebola outbreak, Global Security: Health, Science and Policy To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23779497.2016.1228431 © 2016 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 25 Oct 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rgsh20 Download by: [71.219.210.146] Date: 25 October 2016, At: 20:05 GLOBAL SECURITY: HEALTH, SCIENCE AND POLICY, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23779497.2016.1228431 OPEN ACCESS Managing dangerous pathogens: challenges in the wake of the recent West African Ebola outbreak Akin Abayomia, Rebecca Katzb, Scott Spencec,d, Brian Contone and Sahr M. Gevaof aDivision of Haematology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Tygerberg Hospital, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa; bDepartment of International Health, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA; cGeneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP), Geneva, Switzerland; dVERTIC, London, UK; ePhysio-Fitness Rehabilitation Centre, Freetown, Sierra Leone; fUniversity of Sierra Leone, Freetown, Sierra Leone ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY In the aftermath of the 2014–2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak, there are a multitude of Ebola samples Received 13 May 2016 that are unaccounted for as well as virus samples stored in facilities that do not have an appropriate Accepted 10 August 2016 level of biosecurity and biosafety, creating serious threats to public health and security. -

Essentials of Public Health Preparedness / Rebecca Katz

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE\ OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Essentials of Public Health © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION PreparednessNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Rebecca Katz, MPH, PhD © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © JonesAssistant & Bartlett Professor Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION GeorgeNOT Washington FOR SALE University OR DISTRIBUTION School of Public Health and Health Services Washington, DC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION. 79832_ch00_FM_5987.indd 1 8/24/11 9:22:38 PM © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION World Headquarters Jones & Bartlett Learning 5 Wall Street Burlington, MA 01803 978-443-5000 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC [email protected] NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION www.jblearning.com Jones & Bartlett Learning books and products are available through most bookstores and online booksellers. -

Learning from the 2017 Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 64 Number 1 Internationalism and Sovereignty Article 6 (Fall 2019) 4-23-2020 International Institutions and Ebola Response: Learning from the 2017 Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo Sam Halabi University of Missouri School of Law, [email protected] Rebecca Katz Georgetown University Medical Center, [email protected] Amanda McClelland Resolve to Save Lives, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Sam Halabi, Rebecca Katz & Amanda McClelland, International Institutions and Ebola Response: Learning from the 2017 Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 64 St. Louis U. L.J. (2020). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol64/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTIONS AND EBOLA RESPONSE: LEARNING FROM THE 2017 OUTBREAK IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO† SAM HALABI,* REBECCA KATZ** & AMANDA MCCLELLAND*** INTRODUCTION On July 17, 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the Ebola outbreak in east Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) under the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR), the fifth declaration since the agreement entered into force in 2007.1 Despite availability of a vaccine and the introduction of a second vaccine candidate, the current Ebola outbreak has not been brought under control. -

Has Global Health Law Risen to Meet the COVID-19 Challenge? Revisiting the International Health Regulations to Prepare for Future Threats

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2020 Has Global Health Law Risen to Meet the COVID-19 Challenge? Revisiting the International Health Regulations to Prepare for Future Threats Lawrence O. Gostin Roojin Habibi Benjamin Mason Meier This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2264 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3598165 This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, and the International Humanitarian Law Commons Global Health Law Column Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics Forthcoming June 2020 Has Global Health Law Risen to Meet the COVID-19 Challenge? Revisiting the International Health Regulations to Prepare for Future Threats Lawrence O. Gostin, Roojin Habibi & Benjamin Mason Meier Introduction Global health law is essential in responding to the infectious disease threats of a globalizing world, where no single country, or border, can wall off disease. Yet, the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic has tested the essential legal foundations of the global health system. Within weeks, the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus has circumnavigated the globe, bringing the world to a halt and exposing the fragility of the international legal order. Reflecting on how global health law will emerge in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, it will be crucial to examine the lessons learned in the COVID-19 response and the reforms required to rebuild global health institutions while maintaining core values of human rights, rule of law, and global solidarity in the face of unprecedented threats. -

The Revised International Health Regulations: a Framework for Global Pandemic Response

The Revised International Health Regulations: A Framework for Global Pandemic Response Rebecca Katz and Julie Fischer The 2009 H1N1 influenza outbreak tested the revised International Health Regulations [IHR (2005)] robustly for the first time. The IHR (2005) contributed to swift international notification, allowing nations to implement their pandemic preparedness plans while Mexico voluntarily adopted stringent social distancing measures to limit further disease spread – factors that probably delayed sustained human-to-human transmission outside the Americas. While the outbreak revealed unprecedented efficiency in international communications and cooperation, it also revealed weaknesses at every level of government. The response raises questions regarding the extent to which the IHR (2005) can serve as a framework for global pandemic response and the balance between global governance of disease control measures and national sovereignty. INTRODUCTION On April 25, 2009, the Director General of the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel H1N1 influenza virus outbreak unfolding in North America a public health emergency of international concern. The notification, communications, and international collaboration leading up to this declaration all took place within the framework of the Revised International Health Regulations [IHR (2005)]. The 2009 H1N1 pandemic marked the first use of the IHR (2005) to address a global public health emergency and was for the most part successfully. This experience, however, raises larger questions about how the IHR (2005) and the associated powers conferred on WHO contribute to and operationalize the concept of global governance of disease. As much as the H1N1 experience demonstrated the power of the IHR (2005), it also highlighted the shortcomings, particularly reliance on uneven national capacities and limited responses to states that exceeded evidence-based public health, trade, and travel recommendations. -

Georgetown Global Health Center Issues Pandemic Preparedness Report and COVID-19 Lessons 14 September 2020

Georgetown Global Health Center issues pandemic preparedness report and COVID-19 lessons 14 September 2020 SJD, LLM, LLB and global health security expert Rebecca Katz, Ph.D., MPH. The work of this report informed the GPMB 2020 Annual Report also released today. Phelan and Katz have identified key strategies to re- center and improve governance preparedness: 1. Re-establish global norms of solidarity and multilateral cooperation, including through critical reform of the International Health Regulations; 2. Consider new mechanisms to support data sharing, research and development, and Credit: CC0 Public Domain equitable access to diagnostics, treatments, vaccines, and medical goods; 3. Immediately address funding constraints on the World Health Organization through In a new report commissioned by the Global increases in assessed contributions; Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB), 4. Develop frameworks and processes for Georgetown global health experts say the success more cohesive and responsive coordination of any effort to redress pandemic preparedness between international institutions and failures demonstrated by COVID-19 requires a re- instilling pandemic preparedness in all centering of governance that would include greater policies at the international level; and accountability, transparency, equity, participation 5. Actively incorporate principles of good and the rule of law. governance into international and national decision-making bodies and processes. The report, Governance Preparedness: Initial Lessons from COVID-19, was published today by Using lessons from governance of other global the Center for Global Health Science and Security challenges, the authors say these strategies would at Georgetown University Medical Center. ensure better preparedness for collective action and financing in the medium- and long-term future. -

Curriculum Vitae Autobiographical Article: from A

LAWRENCE O. GOSTIN Curriculum Vitae Phone: +1 202 662-9373 Georgetown University Law Center Email: [email protected] 600 New Jersey Ave., NW Washington, DC 20001 WEBSITES INTERNET RESOURCES Autobiographical Article: From a Civil Libertarian to a Sanitarian, 34 J. LAW & SOCIETY 594-616 (Dec 2007) The Lancet Profile: Lawrence Gostin: Legal Activist in the Cause of Global Health, 386 THE LANCET 2133 (Nov 28, 2015). Faculty Profile O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law: Global Health & Human Rights Database, in partnership with the WHO and Lawyers’ Collective of India. O’Neill Institute, Prof. Gostin’s Health Tips Georgetown Law Faculty Profile Public Health Post Profile SCHOLARLY PRODUCTIVITY AND IMPACT A systematic empirical analysis of legal scholarship, independent researchers ranked Prof. Gostin 1st in the nation in productivity among all law professors, and 11th in impact and influence. In 2017, researchers ranked Professor Gostin 1st in the nation in citations for health law. Prof. Gostin is also ranked first among health law professors on Google Scholar and on West Law (2018). He is in the top 10% worldwide for downloads on SSRN. MAJOR GLOBAL HEALTH CAMPAIGNS THE JOINT ACTION AND LEARNING INITIATIVE: TOWARDS A FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON GLOBAL HEALTH In 2008, at the founding of the O’Neill Institute, Prof. Gostin proposed a Framework Convention on Global Health founded on the right to health, published in the Georgetown Law Journal. A decade later, in 2018, civil society organizations from every region of the world launched the Framework Convention on Global Health Alliance. The groundwork for the Alliance had been laid by the Joint Action and Learning Initiative on National and Global Responsibilities for Health and the Platform for an FCGH. -

The US and Global Health Security at a Time of Transition

The U.S. and Global Health Security at a Time of Transition Monday, March 12, 2018 2:00 – 3:30 p.m. BIOGRAPHIES Beth Cameron Beth Cameron is NTI’s vice president for global biological policy and programs. Cameron previously served as the senior director for global health security and biodefense on the White House National Security Council (NSC) staff, where she was instrumental in developing and launching the Global Health Security Agenda and addressed homeland and national security threats surrounding biosecurity and biosafety, biodefense, emerging infectious disease threats, biological select agents and toxins, dual‐use research, and bioterrorism. From 2010‐2013, Cameron served as office director for Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) and senior advisor for the Assistant Secretary of Defense for nuclear, chemical and biological defense programs. In this role, she oversaw implementation of the geographic expansion of the Nunn‐Lugar CTR program. For her work, she was awarded the Office of the Secretary of Defense Medal for Exceptional Civilian Service. From 2003‐2010 Cameron oversaw expansion of Department of State Global Threat Reduction programs and supported the expansion and extension of the Global Partnership Against the Spread of Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction, a multilateral framework to improve global CBRN security. Cameron served as an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) fellow in the health policy office of Senator Edward M. Kennedy where she worked on the Patients’ Bill of Rights, medical privacy, and legislation to improve the quality of cancer care. From 2001‐2003, she served as a manager of policy research for the American Cancer Society.