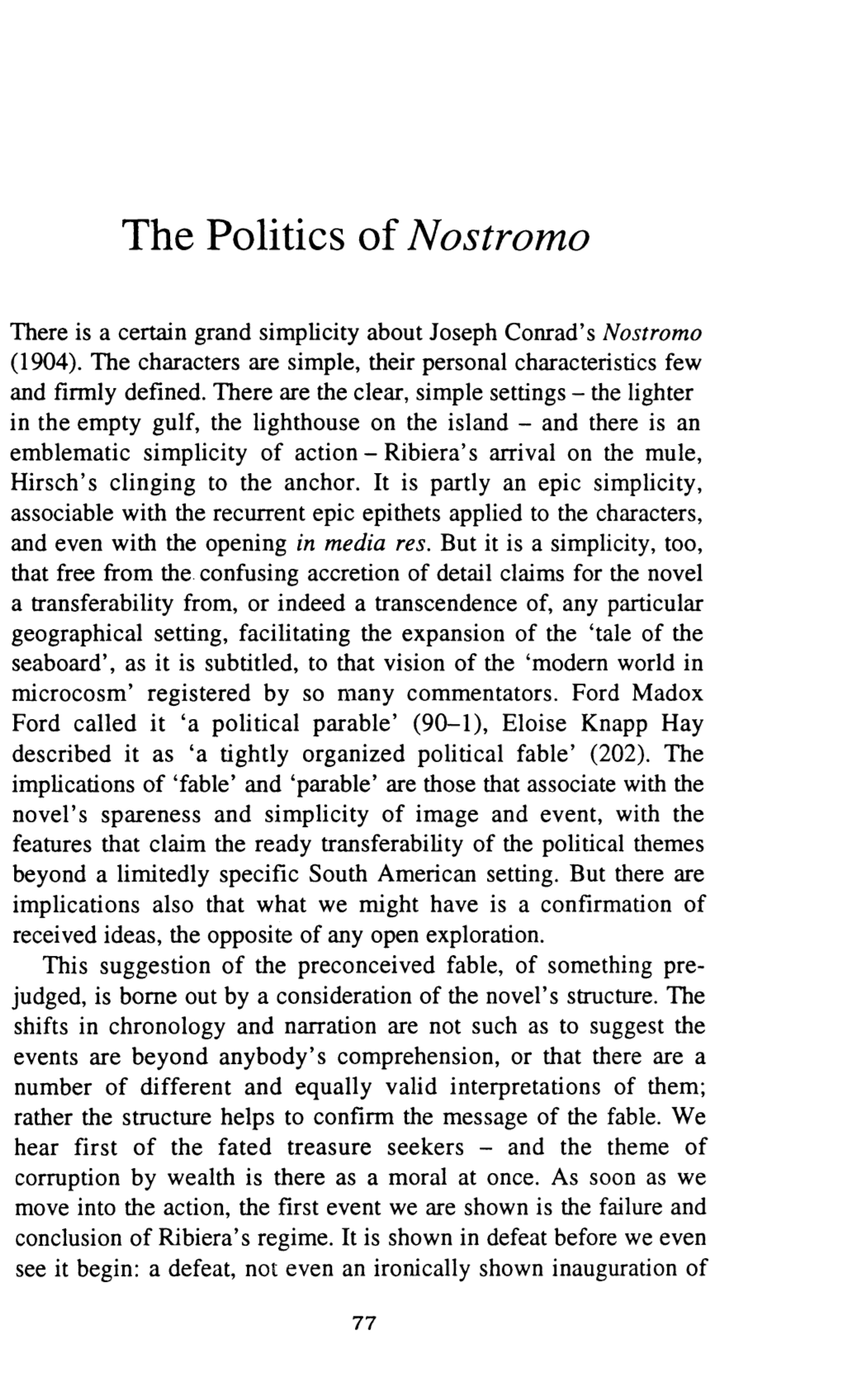

The Politics of Nostromo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nostromo a Tale of the Seaboard

NOSTROMO A TALE OF THE SEABOARD By Joseph Conrad "So foul a sky clears not without a storm." —SHAKESPEARE TO JOHN GALSWORTHY Prepared and Published by: Ebd E-BooksDirectory.com AUTHOR'S NOTE "Nostromo" is the most anxiously meditated of the longer novels which belong to the period following upon the publication of the "Typhoon" volume of short stories. I don't mean to say that I became then conscious of any impending change in my mentality and in my attitude towards the tasks of my writing life. And perhaps there was never any change, except in that mysterious, extraneous thing which has nothing to do with the theories of art; a subtle change in the nature of the inspiration; a phenomenon for which I can not in any way be held responsible. What, however, did cause me some concern was that after finishing the last story of the "Typhoon" volume it seemed somehow that there was nothing more in the world to write about. This so strangely negative but disturbing mood lasted some little time; and then, as with many of my longer stories, the first hint for "Nostromo" came to me in the shape of a vagrant anecdote completely destitute of valuable details. As a matter of fact in 1875 or '6, when very young, in the West Indies or rather in the Gulf of Mexico, for my contacts with land were short, few, and fleeting, I heard the story of some man who was supposed to have stolen single-handed a whole lighter-full of silver, somewhere on the Tierra Firme seaboard during the troubles of a revolution. -

Apocalypse Now

Sabrina Baiguera Università degli Studi di Bergamo Letteratura Anglo-americana LMI A.A. 2011/2012 Paolo Jachia’s Francis Ford Coppola: Apocalypse Now. Un’analisi semiotica , an intertextual reconstruction of the texts, of the cultural references that lie behind the film. Apocalypse Now (1979) Two versions: the orginal version (1979) and the extended version ( Apocalypse Now Redux: 2001 ), released in 2001. The film is set during the Vietnam war (the action takes place approximately in 1970) It tells the story of U.S. Army Captain Benjamin L. Willard who has the mission to proceed up the Nung river into Cambodia, find Colonel Kurtz and “terminate” his command, by whatever means available. Willard starts a journey up the Nung river on a PBR (Petrol Boat) with a four- man crew (Chef – a saucier; Chief – the chief of the boat; Clean – a 17 year- old young from Bronx; Lance – a professional surfer). Kurtz had deserted the U.S. Army to start his own private war in the middle of the jungle. There he is worshipped as a god by his own Montagnard army, but he has gone insane and his methods are “unsound”. The artistic dimension Source texts of Apocalypse Now : 1. Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (1899) 2. James G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890) 3. Jessie Weston’s From ritual to romance (1920) 4. Goethe’s Faust (1808) 5. The Holy Bible 6. T.S.Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922) and The Hollow Men (1925) 7. Baudelaire’s The Albatross (1861) 8. The Doors’ The End Heart of Darkness (1899) “In the case of “Apocalypse,” there was a script written by the great John Milius, but, I must say, what I really made the film from was the little green copy of Heart of Darkness that I had done all those lines in.” (Coppola) Heart of Darkness was not credited as a source text when the film first came out. -

The Ballyhooed Art of Governing Romance

5 The Ballyhooed Art of Governing Romance Interest in The Sheik continued to build and a studio press agent was assigned as a buffer between Valentino and the press. Irving Shulman, Valentino, 19671 One of the striking characteristics of the era of Coolidge Prosperity was the unparalleled rapidity and unanimity with which millions of men and women turned their attention, their talk, and their emotional interests upon a series of tremendous trifles—a heavyweight boxing-match, a murder trial, a new automobile model, a transatlantic flight. Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday, 19312 A “POISONOUSLY SALACIOUS” BESTSELLER The year 1921 turned out to be magical for Valentino even though the aftermath of the success of The Four Horsemen was anything but rosy. After Camille, he and Mathis left Metro Pictures to join Famous Players–Lasky. It was an ambitious move for both of them, but Valentino was also motivated by his frustrations with Metro’s unwillingness to raise his salary and public profile substantially despite the success of The Four Horsemen. Upon learning that Metro underappreciated Valentino’s star potential, Jesse Lasky hired him and then paired him with Mathis, whom he had just lured away from the same company, to work on The Sheik. Before their move, Lasky had acquired the filming rights to the eponymous British best-selling novel and for a while remained unsure whether to turn it into a film.The Sheik had first become a smashing success in the United Kingdom, eventually going through 108 printings between its release in 1919 and 1923, but as overwhelming as the novel’s British popularity was, it “could not compare with its bedazzling success in the United States.”3 The novel had something mysterious about it: the gender of the unknown author, E. -

Reading Conrad Through Cognitive Poetics

International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences Online: 2015-05-15 ISSN: 2300-2697, Vol. 52, pp 44-54 doi:10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILSHS.52.44 CC BY 4.0. Published by SciPress Ltd, Switzerland, 2015 ‘Minding’ the Style: Reading Conrad through Cognitive Poetics Alireza Parandeh, Hossein Pirnajmuddin Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Foreign Languages, University of Isfahan, Azadi Square, Isfahan, Iran E-mail address: [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Cognitive Poetics; Joseph Conrad; Mind Modeling; Theory of Mind; Impressionism; Deixis; Style ABSTRACT. Cognitive Poetics works on the triangle of author-text-reader. A main focus is the reader of literature, as a co-producer of the text alongside the author, in an attempt to explain how his/her knowledge and experiences are applied in reaching an understanding of a particular text in a particular context. In this paper several examples of how contextual frames can operate in a narrative are discussed in three works of short fiction by Joseph Conrad. Analyzed in the particular context of Conradian narrative and prose style are such points as: how the readers begin a story, how they enter into the interior levels of it in order to feel and touch the events in the way its characters do, how they follow every episode of it and, in other words, how the readers ‘comprehend’ the narrative. It is argued that the application of insights from cognitive poetics to Conrad’s fiction is of particular relevance as Conrad is a writer who embodies and foregrounds this very act and process of ‘comprehending’ in his fiction. -

UMA LEITURA DE NOSTROMO, DE JOSEPH CONRAD E HISTÓRIA SECRETA DE COSTAGUANA, DE JUAN GABRIEL VÁSQUEZ Lucilene Canilha Ribeiro (FURG)

A VOZ E A VEZ DO DISCURSO AMERICANO: UMA LEITURA DE NOSTROMO, DE JOSEPH CONRAD E HISTÓRIA SECRETA DE COSTAGUANA, DE JUAN GABRIEL VÁSQUEZ Lucilene Canilha Ribeiro (FURG) A conquista do continente americano pelos navegadores europeus sempre foi uma problemática mal resolvida do ponto de vista do “conquistado”. A aceitação da chegada dos aventureiros às praias do “Novo Mundo” – como foi chamado posteriormente – e a colonização desses povos ainda geram muita discussão. O que é irrefutável é nossa condição de sujeito híbrido, que vive as angústias de pertencer, ao mesmo tempo, a duas culturas que inicialmente se antagonizaram: somos fruto da união entre nativos e estrangeiros. Somos o amálgama que José de Alencar, magistralmente, relatou em seu romance Iracema na figura de Moacir, do filho de Iracema e Martim, que nasce na América, mas é levado para a Europa para ser educado. De todas as imagens que esse romance pode nos trazer, talvez essa seja a que mais alimente a angústia de um sujeito pertencente a dois mundos que coexistem ao mesmo tempo em que se interpõem. O americano de hoje já é um sujeito diferenciado com os acréscimos de todas as variáveis trazidas pela globalização. Apesar disso, algumas constantes ainda são pertinentes, tais como a apropriação do discurso acerca do território americano vista pelo europeu. A motivação para essa discussão parte da análise de dois romances, Nostromo (1904), de Joseph Conrad e História secreta de Costaguana (2007), de Juan Gabriel Vásquez, em que a visão sobre o continente americano é problematizada graças à modificação da perspectiva de quem conta a história. -

"Heart of Darkness" and Francis Ford Coppola's "Apocalypse Now" Author(S): Linda Costanzo Cahir Source: Literature/Film Quarterly, Vol

Narratological Parallels in Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness" and Francis Ford Coppola's "Apocalypse Now" Author(s): Linda Costanzo Cahir Source: Literature/Film Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 3 (1992), pp. 181-187 Published by: Salisbury University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43796548 Accessed: 09-10-2019 03:49 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Salisbury University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Literature/Film Quarterly This content downloaded from 143.107.252.211 on Wed, 09 Oct 2019 03:49:42 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Narratological Parallels in Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness and Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now The theme of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness is, as his character Charles Marlow states, the "fascination of the abomination" (31). The novella is a frame-story, won- derfully entangled by a narrative within a narrative, a flashback within a flashback, a series of quotes within quotes. It is a bildungsroman , an initiation into darkness and chaos, calmly framed by a prologue and an epilogue. Heart of Darkness opens with an unnamed narrator's account of an evening spent aboard the yawl Nellie. -

April Alford, Mary Shielding the Amish Witness

The Elyria Public Library System Fiction List Spring 2021 provided by your librarians April Alford, Mary Shielding the Amish Witness – When Faith Cooper seeks refuge in Amish Country she puts everyone she loves in danger, and it is up to her childhood friend Eli to protect her against a ruthless killer who has nothing left to lose. Ames, Jonathan A Man Named Doll -mystery - Happy Doll is a PI living with his dog, George, and working at a local Thai spa.He has two rules: bark loudly and act first. When faced with a violent patron he finds himself out of his depth. Anderson, Natalie Stranded for One Scandalous Week – romance – (Book One in the Rebels, Brothers, Billionaires Series) The innocent, the playboy, and their seven night passion – is it enough to ignite a lifetime of love? Archer, Jeffrey Turn a Blind Eye-mystery- (Book 3 in the William Warwick Chronicle Series) New Detective Inspector William Warwick is tasked to go undercover and expose corruption at the heart of the Metropolitan Police Force. Baldacci, David A Gambling Man -mystery- (Book 2 in the Aloysius Archer Series) When two seemingly unconnected people are murdered at a burlesque club, Archer must dig deep to reveal the connection between the victims. Bannalec, Jean-Luc The Granite Coast Murders -mystery- (Book 6 in the Brittany Mystery Series) Commissaire Dupin returns to investigate a murder at a gorgeous Brittany beach resort. Beck, Kristin Courage My Love -romance- When the Nazi occupation of Rome begins, two courageous young women are plunged deep into the Italian Resistance to fight for their freedom in this captivating debut novel. -

A That Its Tone Is Provided by an Atmosphere of Sinister Darkness Which Is Penetrated Spasnlodically by the Blood-Red Glare of Gaslight

THE "ILLUMINATING QUALITY": IMAGERY AND THEME IN THE SECRET AGENT S ONE reads The Secret Agent he is aware of the fact A that its tone is provided by an atmosphere of sinister darkness which is penetrated spasnlodically by the blood-red glare of gaslight. The object of this study is to make a sys- tematic analysis of this imagery, indicating how it arose from Conrad's inspiration for the novel; how it aids in the presen- tation of character and theme; and how it serves as a device for furthering the author's artistic purp0se.l In the preface to this narrative, Conrad gives the baclc- ground of his inspiration for the subject and for its develop- ment. There were two distinct impressions, derived from two separate occasions, which gave him the idea of writing Winnie Verloc's story, The first of these occasions occurred as Conrad and a friend sat in desultory conversation, during which an attempted bombing of the Greenwich Observatory was mentioned. The friend remarked that the bombing was perpetrated by a man who was "half an idiot" and that his sister committed suicide later. Conrad was conscious that there was an "illuminating quality" about this story: "One felt like a man walking out of a forest on to a plain-there was not much to see but one had plenty of light. No, there was not much to see and, frankly, for a considerable time I didn't even attempt to perceive anything. It was only the illuminating impression that remained" (pp. x-xi)." The second impression was gathered from an obscure book, "the rather summary recollections of an Assistant Commissioner of Police," and the only distinct remembrance Conrad had of the book was of about ten lines of dialogue, The Rice Institute Pamphlet in which Sir William Harcourt, the Home Secretary, re- marked to the Assistant Commissioner that the latter's "idea of secrecy . -

Conrad's Nostromo: Reception, Theme, Technique

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1961 Conrad's Nostromo: Reception, Theme, Technique Jerome A. Long Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Long, Jerome A., "Conrad's Nostromo: Reception, Theme, Technique" (1961). Master's Theses. 1624. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/1624 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1961 Jerome A. Long CONRAD'S NOSTROMO: RECEPTION, THEME .. TECHNIQUE By Jerome A. Long A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty ot the Graduate School ot Loyola University in Partial Fulf11lment ot the Requ1rements for the Degree of Master of Arts February 1961 LIPS Jerome A. Long wa. born in Chicago. Illinois. December 20. 1935. He wa. graduated from Loyola Academy, Chioago. Illinois, June. 1953. and .a. graduated trom Loyola University. Chicago, June. 1957. with the degree ot Bachelor ot Sclence. , He .as enrolled in the Graduate School of Lolol a university in June. 1957. as a candidate tor the degree ot Master of Arts. The following lear he .8S an Instructor in English at Xavier university ot Loui.iana. lew Orleans. In 1959. he became a text book editor at Scott ,oresman and Company. -

IN Ronald J. Ambrosetti a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School

A STUDY OP THE SPY GENRE IN RECENT POPULAR LITERATURE Ronald J. Ambrosetti A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY August 1973 11 ABSTRACT The literature of espionage has roots which can be traced as far back as tales in the Old Test ament. However, the secret agent and the spy genre remained waiting in the wings of the popular stage until well into the twentieth century before finally attracting a wide audience. This dissertation analyzed the spy genre as it reflected the era of the Cold War. The Damoclean Sword of the mid-twentieth century was truly the bleak vision of a world devastated by nuclear pro liferation. Both Western and Communist "blocs" strove lustily in the pursuit of the ultimate push-button weapons. What passed as a balance of power, which allegedly forged a détente in the hostilities, was in effect a reign of a balance of terror. For every technological advance on one side, the other side countered. And into this complex arena of transis tors and rocket fuels strode the secret agent. Just as the detective was able to calculate the design of a clock-work universe, the spy, armed with the modern gadgetry of espionage and clothed in the accoutrements of the organization man as hero, challenged a world of conflicting organizations, ideologies and technologies. On a microcosmic scale of literary criticism, this study traced the spy genre’s accurate reflection of the macrocosmic pattern of Northrop Frye’s continuum of fictional modes: the initial force of verisimili tude was generated by Eric Ambler’s early realism; the movement toward myth in the technological romance of Ian Fleming; the tragic high-mimesis of John Le Carre' and the subsequent devolution to low-mimesis in the spoof; and the final return to myth in religious affir mation and symbolism. -

Mimesis, Romance, Novel: Representation of Milieu in the Monk and Nostromo

MIMESIS, ROMANCE, NOVEL: REPRESENTATION OF MILIEU IN THE MONK AND NOSTROMO. A Thesis submitted to the faculty of ry < San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for ^3^ thC Degree Master of Arts In English: Literature by Sudarshan Ramani San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Sudarshan Ramani 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Mimesis, Romance, Novel: Representation of Milieu in The Monk and Nostromo by Sudarshan Ramani, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in English: Literature at San Francisco State University. MIMESIS, ROMANCE, NOVEL: REPRESENTATION OF MILIEU IN THE MONK AND NOSTROMO Sudarshan Ramani San Francisco, California 2018 ABSTRACT: The century that separates M. G. Lewis’s The Monk (1796) and Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo (1904) is a century of historical and aesthetic revolution. Paired together, both novels reveal the continuity of the problem of representing reality. Both of these novels are original products of an international outlook that mixes high and low culture, the experimental and the popular, the folkloric and the avant-garde. When viewed in this context, it becomes possible to see the historical and the contemporary in a gothic novel like The Monk, and the gothic and the fantastic in a historical novel like Nostromo. Following the example of Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis, this thesis focuses on the presence of contingent and dynamic elements in the narrative style of these two novels so as to better explain their originality, and the ways in which both authors continue to challenge the static pillars of tradition and cultural inheritance. -

Warm up Discuss These Questions with a Partner

2 LOVE AND ATTRACTION Lovebirds mate for life, and mating pairs are often seen sitting close together for long periods of time. Warm Up Discuss these questions with a partner. 1. What are some things that animals do to attract a mate? 2. What is it that makes one person attractive to another? 3. In what ways do you think science might explain feelings of love? 25 46927_ch02_ptg01_hr_025-042_06.indd 25 9/25/14 10:59 PM Before You Read A. Discussion. Check (✓) whether you agree or disagree with the following statements about love. Then explain your answers to a partner. Agree Disagree 1. The idea of romantic love is a modern one. 2. The feeling of love is caused by chemicals in the brain. 3. Attitudes about love are basically the same in all cultures. 4. The feeling of romantic love usually only lasts a short time. 5. Arranged marriages are likely to last longer than ones started in romance. B. Scan. You are going to read about some specialists’ beliefs about love. Quickly scan the reading on pages 27–29. Then match the people on the left with their professions on the right. 1. Thomas Lewis a. Swiss university professor 2. Claus Wedekind b. Italian university professor 3. Donatella Marazziti c. American anthropologist 4. Helen Fisher d. American psychiatrist 26 Unit 2A 46927_ch02_ptg01_hr_025-042_06.indd 26 9/25/14 10:59 PM 2A LOVE: A CHEMICAL REACTION? Newlyweds dressed in Han-dynasty costumes face each other during a traditional group wedding ceremony in Xi’an, China. 1 SOME ANTHROPOLOGISTS1 ONCE THOUGHT that In India, marriages have traditionally been romance was a Western idea, developed in arranged, usually by the bride’s and groom’s the Middle Ages.2 Non-Western societies, they parents, but today love marriages appear to thought, were too occupied with social and be on the rise, often in defiance of parents’ 5 family relationships for romance.