ECL Submission for Solitary Confinement Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CTC Sentinel Objective

NOVEMBER 2010 . VOL 3 . ISSUE 11-12 COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT CTC Sentinel OBJECTIVE . RELEVANT . RIGOROUS Contents AQAP’s Soft Power Strategy FEATURE ARTICLE 1 AQAP’s Soft Power Strategy in Yemen in Yemen By Barak Barfi By Barak Barfi REPORTS 5 Developing Policy Options for the AQAP Threat in Yemen By Gabriel Koehler-Derrick 9 The Role of Non-Violent Islamists in Europe By Lorenzo Vidino 12 The Evolution of Iran’s Special Groups in Iraq By Michael Knights 16 Fragmentation in the North Caucasus Insurgency By Christopher Swift 19 Assessing the Success of Leadership Targeting By Austin Long 21 Revolution Muslim: Downfall or Respite? By Aaron Y. Zelin 24 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 28 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts l-qa`ida in the arabian AQAP has avoided many of the domestic Peninsula (AQAP) is currently battles that weakened other al-Qa`ida the most successful of the affiliates by pursuing a shrewd strategy at three al-Qa`ida affiliates home in Yemen.3 The group has sought to Aoperating in the Arab world.1 Unlike its focus its efforts on its primary enemies— sibling partners, AQAP has neither been the Yemeni and Saudi governments, as plagued by internecine conflicts nor has well as the United States—rather than it clashed with its tribal hosts. It has also distracting itself by combating minor launched two major terrorist attacks domestic adversaries that would only About the CTC Sentinel against the U.S. homeland that were only complicate its grand strategy. Some The Combating Terrorism Center is an foiled by a combination of luck and the analysts have argued that this stems independent educational and research help of foreign intelligence agencies.2 from the lessons the group learned from institution based in the Department of Social al-Qa`ida’s failed campaigns in countries Sciences at the United States Military Academy, such as Saudi Arabia and Iraq. -

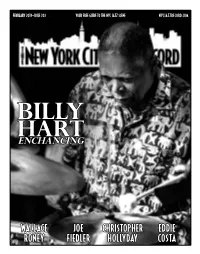

Wallace Roney Joe Fiedler Christopher

feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 YOUr FREE GUide TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BILLY HART ENCHANCING wallace joe christopher eddie roney fiedler hollyday costa Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : wallace roney 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist featUre : joe fiedler 7 by steven loewy [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : Billy hart 8 by jim motavalli [email protected] Advertising: encore : christopher hollyday 10 by robert bush [email protected] Calendar: lest we forGet : eddie costa 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotliGht : astral spirits 11 by george grella [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or oBitUaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] FESTIVAL REPORT 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, CD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Miscellany Tom Greenland, George Grella, 31 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event calendar Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, 32 Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, Steven Loewy, As unpredictable as the flow of a jazz improvisation is the path that musicians ‘take’ (the verb Francesco Martinelli, Annie Murnighan, implies agency, which is sometimes not the case) during the course of a career. -

War Crimes and the Devastation of Somalia WATCH

Somalia HUMAN “So Much to Fear” RIGHTS War Crimes and the Devastation of Somalia WATCH “So Much to Fear” War Crimes and the Devastation of Somalia Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-415-X Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2008 1-56432-415-X “So Much to Fear” War Crimes and the Devastation of Somalia Map of Somalia ............................................................................................................. 1 Map of Mogadishu ....................................................................................................... 2 Summary.......................................................................................................................3 Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 9 To the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia ................................................. 9 To the Alliance for the Re-Liberation of Somalia......................................................10 To Al-Shabaab and other Insurgent groups............................................................ -

Prefering Order to Justice Laura Rovner

American University Law Review Volume 61 | Issue 5 Article 3 2012 Prefering Order to Justice Laura Rovner Jeanne Theoharis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Courts Commons Recommended Citation Rovner, Laura, and Jeanne Theoharis. "Prefering Order to Justice." American University Law Review 61, no.5 (2012): 1331-1415. This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prefering Order to Justice This essay is available in American University Law Review: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol61/iss5/3 ROVNER‐THEOHARIS.OFF.TO.PRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 6/14/2012 7:12 PM PREFERRING ORDER TO JUSTICE ∗ LAURA ROVNER & JEANNE THEOHARIS In the decade since 9/11, much has been written about the “War on Terror” and the lack of justice for people detained at Guantanamo or subjected to rendition and torture in CIA black sites. A central focus of the critique is the unreviewability of Executive branch action toward those detained and tried in military commissions. In those critiques, the federal courts are regularly celebrated for their due process and other rights protections. Yet in the past ten years, there has been little scrutiny of the hundreds of terrorism cases tried in the Article III courts and the state of the rights of people accused of terrrorism-related offenses in the federal system. -

Ohio Terrorism N=30

Terry Oroszi, MS, EdD Advanced Technical Intelligence Center ABC Boonshoft School of Medicine, WSU Henry Jackson Foundation, WPAFB The Dayton Think Tank, Dayton, OH Definitions of Terrorism International Terrorism Domestic Terrorism Terrorism “use or threatened use of “violent acts that are “the intent to instill fear, and violence to intimidate a dangerous to human life the goals of the terrorists population or government and and violate federal or state are political, religious, or thereby effect political, laws” ideological” religious, or ideological change” “Political, Religious, or Ideological Goals” The Research… #520 Charged (2001-2018) • Betim Kaziu • Abid Naseer • Ali Mohamed Bagegni • Bilal Abood • Adam Raishani (Saddam Mohamed Raishani) • Ali Muhammad Brown • Bilal Mazloum • Adam Dandach • Ali Saleh • Bonnell (Buster) Hughes • Adam Gadahn (Azzam al-Amriki) • Ali Shukri Amin • Brandon L. Baxter • Adam Lynn Cunningham • Allen Walter lyon (Hammad Abdur- • Brian Neal Vinas • Adam Nauveed Hayat Raheem) • Brother of Mohammed Hamzah Khan • Adam Shafi • Alton Nolen (Jah'Keem Yisrael) • Bruce Edwards Ivins • Adel Daoud • Alwar Pouryan • Burhan Hassan • Adis Medunjanin • Aman Hassan Yemer • Burson Augustin • Adnan Abdihamid Farah • Amer Sinan Alhaggagi • Byron Williams • Ahmad Abousamra • Amera Akl • Cabdulaahi Ahmed Faarax • Ahmad Hussam Al Din Fayeq Abdul Aziz (Abu Bakr • Amiir Farouk Ibrahim • Carlos Eduardo Almonte Alsinawi) • Amina Farah Ali • Carlos Leon Bledsoe • Ahmad Khan Rahami • Amr I. Elgindy (Anthony Elgindy) • Cary Lee Ogborn • Ahmed Abdel Sattar • Andrew Joseph III Stack • Casey Charles Spain • Ahmed Abdullah Minni • Anes Subasic • Castelli Marie • Ahmed Ali Omar • Anthony M. Hayne • Cedric Carpenter • Ahmed Hassan Al-Uqaily • Antonio Martinez (Muhammad Hussain) • Charles Bishop • Ahmed Hussein Mahamud • Anwar Awlaki • Christopher Lee Cornell • Ahmed Ibrahim Bilal • Arafat M. -

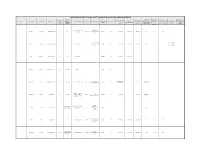

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11/01-12/31/14 Date of Initial Terrorist Country or If Parents Are Defendant's Immigration Status If a U.S. Citizen, Entry or Immigration Status Current Organization Conviction Current Territory of Origin, Citizens, Natural- Number Charge Date Conviction Date Defendant Age at Conviction Offenses Sentence Date Sentence Imposed Last U.S. Residence at Time of Natural-Born or Admission to at Time of Initial Immigration Status Affiliation or District Immigration Status If Not a Natural- Born or Conviction Conviction Naturalized? U.S., If Entry or Admission of Parents Inspiration Born U.S. Citizen Naturalized? Applicable 243 months 18/2339B; 18/922(g)(1); 1 5/27/2014 10/30/2014 Donald Ray Morgan 44 ISIS 5/13/15 imprisonment; 3 years MDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Natural-Born N/A N/A N/A 18/924(a)(2) SR 3 years imprisonment; Unknown. Mother 2 8/29/2013 10/28/2014 Robel Kidane Phillipos 19 2x 18/1001(a)(2) 6/5/15 3 years SR; $25,000 DMA MA U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Naturalized Ethiopia came as a refugee fine from Ethiopia. 3 4/1/2014 10/16/2014 Akba Jihad Jordan 22 ISIS 18/2339A EDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen 4 9/24/2014 10/3/2014 Mahdi Hussein Furreh 31 Al-Shabaab 18/1001 DMN MN 25 years Lawful Permanent 5 11/28/2012 9/25/2014 Ralph Kenneth Deleon 26 Al-Qaeda 18/2339A; 18/956; 18/1117 2/23/15 CDCA CA N/A Philippines imprisonment; life SR Resident 18/2339A; 18/2339B; 25 years 6 12/12/2012 9/25/2014 Sohiel Kabir 37 Al-Qaeda 18/371 (1812339D 2/23/15 CDCA CA U.S. -

Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans Author: David Schanzer, Charles Kurzman, Ebrahim Moosa Document No.: 229868 Date Received: March 2010 Award Number: 2007-IJ-CX-0008 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Anti- Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans DAVID SCHANZER SANFORD SCHOOL OF PUBLIC POLICY DUKE UNIVERSITY CHARLES KURZMAN DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL EBRAHIM MOOSA DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION DUKE UNIVERSITY JANUARY 6, 2010 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Project Supported by the National Institute of Justice This project was supported by grant no. -

A Film by Lyric R. Cabral and David Felix Sutcliffe

A film by Lyric R. Cabral and David Felix Sutcliffe (T)ERROR is the first film to infiltrate a covert counterterrorism sting, with filmmakers documenting the action in real time as it unfolds on the ground. Viewers get an unfettered glimpse of the government's counterterrorism tactics and the murky justifications behind them through the perspective of a 63-year-old Black revolutionary turned FBI informant. 84 minutes Domestic Sales Contact: CAA Tristen Tuckfield, [email protected], 424-288-2000 International Sales Contact: ro*co Annie Rooney, [email protected], 415-332-6471 x200 SYNOPSIS (T)ERROR is the first documentary to place filmmakers on the ground during an active FBI counterterrorism sting operation. Through the perspective of "Shariff," a 63-year-old Black revolutionary turned informant, viewers get an unfettered glimpse of the government's counterterrorism tactics and the murky justifications behind them. The film begins in an undisclosed location in eastern United States. Shariff (whose legal name is Saeed Torres) works as a cook in a middle school cafeteria, but is struggling to make ends meet. When the FBI calls, inviting him to work on a terrorism investigation in Pittsburgh, Shariff reluctantly leaves his young son behind, for what he hopes will be his last case, and a chance to make several hundred thousand dollars. Upon arrival in Pittsburgh, Shariff informs the filmmakers that the FBI has ordered him to befriend a white Muslim convert named Khalifah Al-Akili, and assess his interest in attending a terrorist training camp abroad. As his investigation of Khalifah unfolds, a parallel examination of Shariff begins as well. -

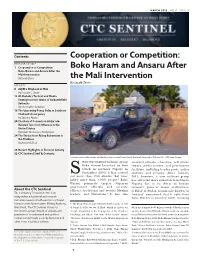

CTC Sentinel 6

MARCH 2013 . VOL 6 . ISSUE 3 Contents Cooperation or Competition: FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Cooperation or Competition: Boko Haram and Ansaru After Boko Haram and Ansaru After the Mali Intervention By Jacob Zenn the Mali Intervention By Jacob Zenn REPORTS 9 AQIM’s Playbook in Mali By Pascale C. Siegel 12 Al-Shabab’s Tactical and Media Strategies in the Wake of its Battlefield Setbacks By Christopher Anzalone 16 The Upcoming Peace Talks in Southern Thailand’s Insurgency By Zachary Abuza 20 The Role of Converts in Al-Qa`ida- Related Terrorism Offenses in the United States By Robin Simcox and Emily Dyer 24 The Threat from Rising Extremism in the Maldives By Animesh Roul 28 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 32 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts A Cameroonian soldier stands in Dabanda by the car of the French family that was kidnapped on February 19. - AFP/Getty Images ince the nigerian militant group attacked schools, churches, cell phone Boko Haram1 launched its first towers, media houses, and government attack in northern Nigeria in facilities, including border posts, police September 2010, it has carried stations and prisons. Since January Sout more than 700 attacks that have 2012, however, a new militant group killed more than 3,000 people.2 Boko has attracted more attention in northern Haram primarily targets Nigerian Nigeria due to its threat to foreign government officials and security interests. Jama`at Ansar al-Muslimin About the CTC Sentinel officers, traditional and secular Muslim fi Bilad al-Sudan (commonly known as The Combating Terrorism Center is an leaders, and Christians.3 It has also Ansaru)4 announced that it split from independent educational and research Boko Haram in January 2012, claiming institution based in the Department of Social Sciences at the United States Military Academy, 1 The group Boko Haram identifies itself as Jama`at Ahl West Point. -

Immigration and Terrorism: Moving Beyond the 9/11 Staff Report on Terrorist Travel Janice L

Immigration and Terrorism: Moving Beyond the 9/11 Staff Report on Terrorist Travel Janice L. Kephart ∗ OH GOD, you who open all doors, please open all doors for me, open all venues for me, open all avenues for me. – Mohammed Atta Introduction In August 2004, on the last day the 9/11 Commission was statutorily permitted to exist, a 240-page staff report describing the 9/11 Commission border team’s fifteen months of work in the area of immigration, visas, and border control was published on the 1 web. Our report, 9/11 and Terrorist Travel, focused on answering the question of how the hijackers of September 11 managed to enter and stay in the United States.2 To do so, we looked closely at the immigration records of the individual hijackers, along with larger policy questions of how and why our border security agencies failed us. The goal of this essay is to build on that report in two areas: • To provide additional facts about the immigration tactics of indicted and con- victed operatives of Al Qaeda, Hamas, Hezbollah, and other terrorist groups from the 1990s through the end of 2004. • To enlarge the policy discussion regarding the relationship between national security and immigration control. This report does not necessarily reflect the views of the 9/11 Commission or its staff. ∗ Janice Kephart is former counsel to the September 11 Commission. She has testified before the U.S. Congress, and has made numerous appearances in print and broadcast media. Re- search used in preparing portions of this report was conducted with the assistance of (former) select staff of the Investigative Project on Terrorism, Josh Lefkowitz, Jacob Wallace, and Jeremiah Baronberg. -

Townload Printable Flyer Regarding Tarik Shah's Case

Some Background for (T)ERROR Included: • Overview of the Tarik Shah “Martial Arts” case • My Story by Tarik Shah • Resources: available reports on preemptive prosecution, book and documentary film about informants, petition for Tarik Shah Justice For Tarik Shah The Facts of the Tarik Shah “Martial Arts” Case Three months after 9/11, on December 1, 2001 provide medical assistance to injured combat- the FBI directed an agent provocateur to go to ants; Sabir, who lived in Florida, was in town Abdulrahman Farhane’s Islamic bookstore in visiting Tarik. The New York Times wrote that New York City and say that he wanted to send “the tapes reveal a plot that was almost entirely some money to jihadist brothers overseas. Far- talk…No weapons appear to have been bought, hane refused to help, and no martial arts but referred the pro- training took place.” vocateur to Tarik The “plot” went on Shah, a well-known for two years, and jazz bass player, self- became a joint FBI/ defense trainer, and NYPD sting operation. martial arts teacher Tarik was arrested in in New York City who May 2005. had played at Presi- At his arrest, Tarik dent Clinton’s inau- was refused legal rep- guration. Tarik did resentation and was nothing, but the pro- threatened with the vocateur, Mohamed PATRIOT Act and ren- Alanssi, continued dition. Neither his at- to try to get Tarik to torney nor his family do something ille- knew where he was gal for three years. until three days after He was reportedly his arrest, when he paid $100,000 for was finally able to get his work. -

Prophetics and Aesthetics of Muslim Jazz Musicians in 20Th Century America Parker Mcqueeney Committee: Marty Ehrlich and Carl Clements

1 S ultans of Swing: Prophetics and Aesthetics of Muslim Jazz Musicians in 20th Century America Parker McQueeney Committee: Marty Ehrlich and Carl Clements 2 3 Table of Contents Introduction….4 West African Sufism in the Antebellum South….12 Developing Islamic Infrastructure….20 Bebop’s “Mohammedan Leanings”....23 Hard Bop Jihad….26 A Different Kind of Cat….37 Islam for the Soul of Jazz….41 Bibliography….51 4 Introduction The arrival of Christopher Columbus to the beaches of San Salvador did not only symbolize the New World’s first contact with white Christian Europeans- but black Muslims as well. Since 1492, Islam has been an essential, yet concealed presence in African diasporic identities. In the the continental US, Muslim slaves often held positions of power on plantations- and in several instances became leaders of revolts. Islam became a tool of resistance and resilience, and a way for a kidnapped people to preserve tradition, knowledge, and spirit. It should come as no surprise to learn that when Islam re-emerged in the African-American consciousness in the postbellum period 1, eventually in harmony with the Black Arts Movement, it not only retained these characteristics, but took on new meanings of prophetics, aesthetics, and resistance in cultural, spiritual, and political contexts. Even in the pre-9/11 dominant American narrative, images of Black Islam conjured up fearful and vague memories of the political and militant Nation of Islam of the 1960s. The popularity of Malcolm X’s autobiography brought this to the forefront of perceptions of Black Islam, and its place in the Black psyche was further cemented by Spike Lee’s 1992 film Malcolm X.