INVENTING TERRORISTS the Lawfare of Preemptive Prosecution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CTC Sentinel Objective

NOVEMBER 2010 . VOL 3 . ISSUE 11-12 COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT CTC Sentinel OBJECTIVE . RELEVANT . RIGOROUS Contents AQAP’s Soft Power Strategy FEATURE ARTICLE 1 AQAP’s Soft Power Strategy in Yemen in Yemen By Barak Barfi By Barak Barfi REPORTS 5 Developing Policy Options for the AQAP Threat in Yemen By Gabriel Koehler-Derrick 9 The Role of Non-Violent Islamists in Europe By Lorenzo Vidino 12 The Evolution of Iran’s Special Groups in Iraq By Michael Knights 16 Fragmentation in the North Caucasus Insurgency By Christopher Swift 19 Assessing the Success of Leadership Targeting By Austin Long 21 Revolution Muslim: Downfall or Respite? By Aaron Y. Zelin 24 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 28 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts l-qa`ida in the arabian AQAP has avoided many of the domestic Peninsula (AQAP) is currently battles that weakened other al-Qa`ida the most successful of the affiliates by pursuing a shrewd strategy at three al-Qa`ida affiliates home in Yemen.3 The group has sought to Aoperating in the Arab world.1 Unlike its focus its efforts on its primary enemies— sibling partners, AQAP has neither been the Yemeni and Saudi governments, as plagued by internecine conflicts nor has well as the United States—rather than it clashed with its tribal hosts. It has also distracting itself by combating minor launched two major terrorist attacks domestic adversaries that would only About the CTC Sentinel against the U.S. homeland that were only complicate its grand strategy. Some The Combating Terrorism Center is an foiled by a combination of luck and the analysts have argued that this stems independent educational and research help of foreign intelligence agencies.2 from the lessons the group learned from institution based in the Department of Social al-Qa`ida’s failed campaigns in countries Sciences at the United States Military Academy, such as Saudi Arabia and Iraq. -

Special Administrative Measures and the War on Terror: When Do Extreme Pretrial Detention Measures Offend the Constitution?

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 19 2014 Special Administrative Measures and the War on Terror: When do Extreme Pretrial Detention Measures Offend the Constitution? Andrew Dalack University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew Dalack, Special Administrative Measures and the War on Terror: When do Extreme Pretrial Detention Measures Offend the Constitution?, 19 MICH. J. RACE & L. 415 (2014). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol19/iss2/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE MEASURES AND THE WAR ON TERROR: WHEN DO EXTREME PRETRIAL DETENTION MEASURES OFFEND THE CONSTITUTION? Andrew Dalack* Our criminal justice system is founded upon a belief that one is innocent until proven guilty. This belief is what foists the burden of proving a person’s guilt upon the government and belies a statutory presumption in favor of allowing a defendant to remain free pending trial at the federal level. Though there are certainly circum- stances in which a federal magistrate judge may—and sometimes must—remand a defendant to jail pending trial, it is well-settled that pretrial detention itself inher- ently prejudices the quality of a person’s defense. -

NYC News Summer 2014

NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD New York City News NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD – NYC CHAPTER SUMMER 2014 Mass Incarceration Launches Parole Preparation Project The NLG-NYC Mass Incarceration six to nine months. date to look at risk, rehabilitation, readiness Committee (MIC) has had an exciting sum- Volunteers will collaborate with parole for release, and an array of other factors mer! On June 11th, we held a training for applicants to gather necessary documentation when determining an individual’s eligibility volunteers interested in participating in for upcoming parole hearings, and work with for release, disproportionately emphasizing the Parole Preparation Project. The Project them on practicing for the actual interview. the seriousness of an individual’s crime of aims to pair volunteers (law students, social Volunteers will also support volunteers in conviction. The results are both unlawful workers, family and friends of incarcerated soliciting meaningful letters of support from and unethical. This flawed system weakens persons among others) with individuals who friends, family, co-workers, and the Project morale among those who have worked hard face long prison sentences and have been will write letters of support as well. to rehabilitate themselves only to find their repeatedly denied parole. Approximately 40 The Project exists in response to our efforts go unrewarded as they are repeatedly people attended the training, most commit- broken New York State parole system. The denied release. ting to working on the project over the next Board of Parole routinely violates its man- In addition, in part because of parole denials, nearly 9,000 elderly persons remain incarcerated throughout New York. Though these individuals recidivate at the low rate INSIDE THIS ISSUE: of approximately 3%, and many suffer from COMMITTEE UPDATES ................................................................................................ -

Translator, Traitor: a Critical Ethnography of a U.S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 Translator, traitor: A critical ethnography of a U.S. terrorism trial Maya Hess Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/226 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] TRANSLATOR, TRAITOR: A CRITICAL ETHNOGRAPHY OF A U.S. TERRORISM TRIAL by MAYA HESS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii © 2014 MAYA HESS All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Criminal Justice in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Diana Gordon ______________________ _____________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Deborah Koetzle ______________________ _____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Susan Opotow __________________________________________ David Brotherton __________________________________________ Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract TRANSLATOR, TRAITOR: A CRITICAL ETHNOGRAPHY OF A U.S. TERRORISM TRIAL by Maya Hess Adviser: Professor Diana Gordon Historically, the role of translators and interpreters has suffered from multiple misconceptions. In theaters of war, these linguists are often viewed as traitors and kidnapped, tortured, or killed; if they work in the terrorism arena, they may be prosecuted and convicted as terrorist agents. -

Conference Program

First Class Mail U.S. Postage SCHOOL OF LAW PAID 121 Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York 11549-1210 Hofstra University Sunday, Monday and Tuesday October 14, 15 and 16, 2007 Conference Director Professor Roy D. Simon Conference Coordinator Dawn Marzella 7 0 / 9 : PROGRAM 0 9 3 7 LEGAL ETHICS: LAWYERING AT THE EDGE UNPOPULAR CLIENTS, DIFFICULT CASES, ZEALOUS ADVOCATES Stuart Rabinowitz Nora V. Demleitner Roy D. Simon President and Andrew M. Boas Interim Dean and Professor of Law Howard Lichtenstein Distinguished and Mark L. Claster Distinguished Hofstra Law School Professor of Legal Ethics Professor of Law, Hofstra University Hofstra Law School Conference Director KEYNOTE ADDRESS BANQUET ADDRESS Michael E. Tigar Gerald B. Lefcourt Research Professor of Law, Washington College of Law, Law Offices of Gerald B. Lefcourt Visiting Professor, Duke Law School New York, NY Professeur Invite, Universite Paul Cezanne CONFERENCE SPEAKERS Lonnie T. Brown, Jr. Glenda Grace Andrew Perlman Associate Professor of Law Visiting Assistant Professor Associate Professor University of Georgia School of Law Hofstra Law School Suffolk University Law School Raymond Brown Jeanne P. Gray Burnele V. Powell Attorney, Greenbaum, Rowe, Smith & Davis Director, Center for Professional Responsibility Miles and Ann Loadholt Professor of Law Woodbridge, NJ American Bar Association University of South Carolina School of Law Alafair S. Burke Bruce Green Roy D. Simon Associate Professor of Law Stein Professor of Law, Fordham University Howard Lichtenstein Distinguished Professor Hofstra Law School School of Law of Legal Ethics, Hofstra Law School James Farragher Campbell Joel Hirschhorn Abbe Smith Attorney, Campbell, DeMetrick & Jacobo Attorney, Hirschhorn & Bieber P.A . -

Wallace Roney Joe Fiedler Christopher

feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 YOUr FREE GUide TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BILLY HART ENCHANCING wallace joe christopher eddie roney fiedler hollyday costa Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : wallace roney 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist featUre : joe fiedler 7 by steven loewy [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : Billy hart 8 by jim motavalli [email protected] Advertising: encore : christopher hollyday 10 by robert bush [email protected] Calendar: lest we forGet : eddie costa 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotliGht : astral spirits 11 by george grella [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or oBitUaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] FESTIVAL REPORT 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, CD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Miscellany Tom Greenland, George Grella, 31 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event calendar Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, 32 Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, Steven Loewy, As unpredictable as the flow of a jazz improvisation is the path that musicians ‘take’ (the verb Francesco Martinelli, Annie Murnighan, implies agency, which is sometimes not the case) during the course of a career. -

War Crimes and the Devastation of Somalia WATCH

Somalia HUMAN “So Much to Fear” RIGHTS War Crimes and the Devastation of Somalia WATCH “So Much to Fear” War Crimes and the Devastation of Somalia Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-415-X Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2008 1-56432-415-X “So Much to Fear” War Crimes and the Devastation of Somalia Map of Somalia ............................................................................................................. 1 Map of Mogadishu ....................................................................................................... 2 Summary.......................................................................................................................3 Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 9 To the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia ................................................. 9 To the Alliance for the Re-Liberation of Somalia......................................................10 To Al-Shabaab and other Insurgent groups............................................................ -

'Health-Care Reform' Aims to Cut Social Wage

· AUSTRALIA $1.50 · CANADA $1.25 · FRANCE 1.00 EURO · NEW ZEALAND $1.50 · SWEDEN KR10 · UK £.50 · U.S. $1.00 INSIDE Venezuela Int’l Book Fair spreads access to culture — PAGE 7 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 73/NO. 46 NOVEMBER 30, 2009 Foreclosures ‘Health-care reform’ Washington mount as aims to cut social wage prepares capitalist Bill imposes fines for those without plans new moves crisis deepens against Iran BY BRIAN WILLIAMS BY CINDY JAQUITH Despite government programs at- November 16—As relations be- tempting to stem the crisis in the tween Washington and Tehran de- capitalist housing market, foreclo- teriorate, the Iranian government is sures continue to rise. The number shifting its tone on President Barack hit a record high in the third quarter Obama, whose election it welcomed. with more than 937,000 filings. So far Moscow, meanwhile, has signaled its this year 3.8 million notices of default willingness to back further actions have been filed, according to Moody’s against Iran if it continues to enrich Economy.com. uranium for its nuclear program. The crisis goes far beyond those Washington and the imperialist who have taken out subprime mort- powers in Europe have demanded gage loans, which require no money Tehran cease enriching uranium, down but have interest rate payments charging it is doing so to build an that increase. Millions who had signed atomic bomb. Tehran denies this, say- up for adjustable rate mortgages AP Photo/Paul Beaty ing it will use the uranium as fuel for (ARM) are facing similar prospects Crowded emergency room at Stroger Hospital in Chicago July 30. -

Prefering Order to Justice Laura Rovner

American University Law Review Volume 61 | Issue 5 Article 3 2012 Prefering Order to Justice Laura Rovner Jeanne Theoharis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Courts Commons Recommended Citation Rovner, Laura, and Jeanne Theoharis. "Prefering Order to Justice." American University Law Review 61, no.5 (2012): 1331-1415. This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prefering Order to Justice This essay is available in American University Law Review: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol61/iss5/3 ROVNER‐THEOHARIS.OFF.TO.PRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 6/14/2012 7:12 PM PREFERRING ORDER TO JUSTICE ∗ LAURA ROVNER & JEANNE THEOHARIS In the decade since 9/11, much has been written about the “War on Terror” and the lack of justice for people detained at Guantanamo or subjected to rendition and torture in CIA black sites. A central focus of the critique is the unreviewability of Executive branch action toward those detained and tried in military commissions. In those critiques, the federal courts are regularly celebrated for their due process and other rights protections. Yet in the past ten years, there has been little scrutiny of the hundreds of terrorism cases tried in the Article III courts and the state of the rights of people accused of terrrorism-related offenses in the federal system. -

Ohio Terrorism N=30

Terry Oroszi, MS, EdD Advanced Technical Intelligence Center ABC Boonshoft School of Medicine, WSU Henry Jackson Foundation, WPAFB The Dayton Think Tank, Dayton, OH Definitions of Terrorism International Terrorism Domestic Terrorism Terrorism “use or threatened use of “violent acts that are “the intent to instill fear, and violence to intimidate a dangerous to human life the goals of the terrorists population or government and and violate federal or state are political, religious, or thereby effect political, laws” ideological” religious, or ideological change” “Political, Religious, or Ideological Goals” The Research… #520 Charged (2001-2018) • Betim Kaziu • Abid Naseer • Ali Mohamed Bagegni • Bilal Abood • Adam Raishani (Saddam Mohamed Raishani) • Ali Muhammad Brown • Bilal Mazloum • Adam Dandach • Ali Saleh • Bonnell (Buster) Hughes • Adam Gadahn (Azzam al-Amriki) • Ali Shukri Amin • Brandon L. Baxter • Adam Lynn Cunningham • Allen Walter lyon (Hammad Abdur- • Brian Neal Vinas • Adam Nauveed Hayat Raheem) • Brother of Mohammed Hamzah Khan • Adam Shafi • Alton Nolen (Jah'Keem Yisrael) • Bruce Edwards Ivins • Adel Daoud • Alwar Pouryan • Burhan Hassan • Adis Medunjanin • Aman Hassan Yemer • Burson Augustin • Adnan Abdihamid Farah • Amer Sinan Alhaggagi • Byron Williams • Ahmad Abousamra • Amera Akl • Cabdulaahi Ahmed Faarax • Ahmad Hussam Al Din Fayeq Abdul Aziz (Abu Bakr • Amiir Farouk Ibrahim • Carlos Eduardo Almonte Alsinawi) • Amina Farah Ali • Carlos Leon Bledsoe • Ahmad Khan Rahami • Amr I. Elgindy (Anthony Elgindy) • Cary Lee Ogborn • Ahmed Abdel Sattar • Andrew Joseph III Stack • Casey Charles Spain • Ahmed Abdullah Minni • Anes Subasic • Castelli Marie • Ahmed Ali Omar • Anthony M. Hayne • Cedric Carpenter • Ahmed Hassan Al-Uqaily • Antonio Martinez (Muhammad Hussain) • Charles Bishop • Ahmed Hussein Mahamud • Anwar Awlaki • Christopher Lee Cornell • Ahmed Ibrahim Bilal • Arafat M. -

More Than Just a Few" Bad Apples

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Resist Newsletters Resist Collection 8-30-2004 Resist Newsletter, July-Aug 2004 Resist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter Recommended Citation Resist, "Resist Newsletter, July-Aug 2004" (2004). Resist Newsletters. 364. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter/364 Inside: Resisting Prison and Military Abuse ISSN 0897-2613 • Vol. 13 #6 A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority July/August 2004 More Than Just a Few "Bad Apples" Confronting Prison Problems in Iraq and in the US Zimbardo had students play the roles of ROSEBRAZ guards and prisoners. The study had to be halted after only a few days when the ondemning the abuse of Iraqi pris "guards" began to abuse their fellow stu oners as "fundamentallyun-Ameri dent "prisoners." In a recent Boston Globe Ccan," Donald Rumsfeld ignores the editorial (May 9, 2004) comparing his strikingly similar circumstances facing two experiment's finding with the abuses in million US prisoners. Abu Ghraib, Zimbardo wrote: While Congress, the military-and pun Some of the necessary ingredients [ for dits alike argue that the Abu Ghraib pho stirring human nature in negative direc tos do not depict conditions in American tions] are: diffusion of responsibility, prisons, they forget that a few months be anonymity, dehumanization, peers who fore atrocities were caught on tape at Abu model harmful behavior, bystanders who. Ghraib, we watched our own videotape of A banner depicting abuse at Abu Ghraib do not intervene, and a setting of power guards at the California Youth Authority prison spans a Los Angeles overpass. -

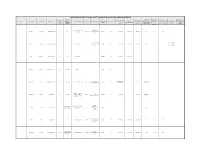

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11/01-12/31/14 Date of Initial Terrorist Country or If Parents Are Defendant's Immigration Status If a U.S. Citizen, Entry or Immigration Status Current Organization Conviction Current Territory of Origin, Citizens, Natural- Number Charge Date Conviction Date Defendant Age at Conviction Offenses Sentence Date Sentence Imposed Last U.S. Residence at Time of Natural-Born or Admission to at Time of Initial Immigration Status Affiliation or District Immigration Status If Not a Natural- Born or Conviction Conviction Naturalized? U.S., If Entry or Admission of Parents Inspiration Born U.S. Citizen Naturalized? Applicable 243 months 18/2339B; 18/922(g)(1); 1 5/27/2014 10/30/2014 Donald Ray Morgan 44 ISIS 5/13/15 imprisonment; 3 years MDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Natural-Born N/A N/A N/A 18/924(a)(2) SR 3 years imprisonment; Unknown. Mother 2 8/29/2013 10/28/2014 Robel Kidane Phillipos 19 2x 18/1001(a)(2) 6/5/15 3 years SR; $25,000 DMA MA U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Naturalized Ethiopia came as a refugee fine from Ethiopia. 3 4/1/2014 10/16/2014 Akba Jihad Jordan 22 ISIS 18/2339A EDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen 4 9/24/2014 10/3/2014 Mahdi Hussein Furreh 31 Al-Shabaab 18/1001 DMN MN 25 years Lawful Permanent 5 11/28/2012 9/25/2014 Ralph Kenneth Deleon 26 Al-Qaeda 18/2339A; 18/956; 18/1117 2/23/15 CDCA CA N/A Philippines imprisonment; life SR Resident 18/2339A; 18/2339B; 25 years 6 12/12/2012 9/25/2014 Sohiel Kabir 37 Al-Qaeda 18/371 (1812339D 2/23/15 CDCA CA U.S.