Chapter 8: Preservation Expenditures and Funding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

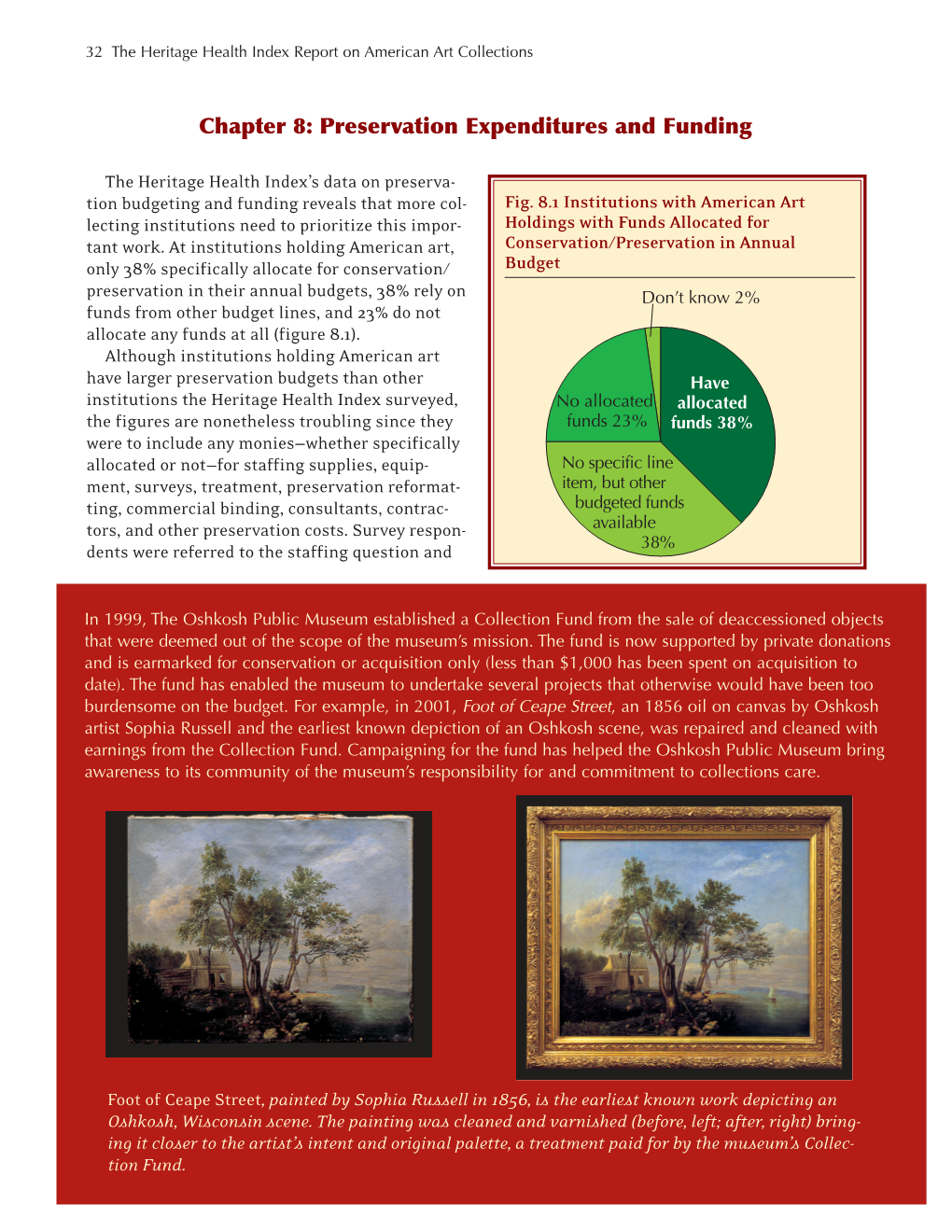

Recommended publications

-

Introducticn Tc Ccnservoticn

introducticntc ccnservoticn UNITED NATTONSEDUCATIONA],, SCIEIilIIFTC AND CULTIJRALOROANIZATTOII AN INIRODUCTION TO CONSERYATIOI{ OF CULTURAT PROPMTY by Berr:ar"d M. Feilden Director of the Internatlonal Centre for the Preservatlon and Restoratlon of Cultural Property, Rome Aprll, L979 (cc-ig/ws/ttt+) - CONTENTS Page Preface 2 Acknowledgements Introduction 3 Chapter* I Introductory Concepts 6 Chapter II Cultural Property - Agents of Deterioration and Loss . 11 Chapter III The Principles of Conservation 21 Chapter IV The Conservation of Movable Property - Museums and Conservation . 29 Chapter V The Conservation of Historic Buildings and Urban Conservation 36 Conclusions ............... kk Appendix 1 Component Materials of Cultural Property . kj Appendix 2 Access of Water 53 Appendix 3 Intergovernmental and Non-Governmental International Agencies for Conservation 55 Appendix k The Conservator/Restorer: A Definition of the Profession .................. 6? Glossary 71 Selected Bibliography , 71*. AUTHOR'S PREFACE Some may say that the attempt to Introduce the whole subject of Conservation of Cultural Propety Is too ambitious, but actually someone has to undertake this task and it fell to my lot as Director of the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cxiltural Property (ICCROM). An introduction to conservation such as this has difficulties in striking the right balance between all the disciplines involved. The writer is an architect and, therefore, a generalist having contact with both the arts and sciences. In such a rapidly developing field as conservation no written statement can be regarded as definite. This booklet should only be taken as a basis for further discussions. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In writing anything with such a wide scope as this booklet, any author needs help and constructive comments. -

January 28, 2021 Introductions Faculty

Art Conservation Open House January 28, 2021 Introductions Faculty Debra Hess Norris Dr. Jocelyn Alcántara-García Brian Baade Maddie Hagerman Dr. Joyce Hill Stoner Nina Owczarek Photograph Conservator Conservation Scientist Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Chair and Professor of Photograph Associate Professor Assistant Professor Instructor Edward F. and Elizabeth Goodman Rosenberg Assistant Professor Conservation Professor of Material Culture Unidel Henry Francis du Pont Chair Students Director, Preservation Studies Doctoral Program Annabelle Camp Kelsey Marino Katie Rovito Miriam-Helene Rudd Art conservation major, Class of 2019 Art conservation major, Class of 2020 WUDPAC Class of 2022 Senior art conservation major, WUDPAC Class of 2022 Preprogram conservator Paintings major Class of 2021 Textile major, organic objects minor President of the Art Conservation Club What is art conservation? • Art conservation is the field dedicated to preserving cultural property • Preventive and interventive • Conservation is an interdisciplinary field that relies heavily on chemistry, art history, history, anthropology, ethics, and art Laura Sankary cleans a porcelain plate during an internship at UD Art Conservation at the University of Delaware • Three programs • Undergraduate degree (BA or BS) • Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation or WUDPAC (MS) at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library near Wilmington, DE • Doctorate in Preservation Studies (PhD) Miriam-Helene Rudd cleans a -

CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015

CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015 **THE HOOD MUSEUM OF ART DOES NOT RECOMMEND SPECIFIC CONSERVATORS. THIS LISTING IS MADE FOR PURPOSES OF INFORMATION ONLY.** Online directory of members of AIC (American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic works): www.conservation-us.org/membership/find-a-conservator GENERAL – Also see individual media below Straus Center for conservation and Technical Studies Harvard University Art Museums 32 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Paper, Objects, Textiles P: 617/495.2392 F: 617/495.0322 Website: www.harvardartmuseums.org Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum 25 Evans Way Boston, MA 02115 P: 617/566.1401 Paper, Objects, Textiles F: 617/278.5167 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gardnermuseum.org Vermont Museum and Gallery Alliance C/O Fairbanks Museum Referrals. Good source for general 1302 Main Street information on storage, packing, and St. Johnsbury, VT 05819 care of artwork. P: 802/751.8381 Williamstown Art Conservation Center, Inc. 227 South Street Williamstown, MA 02167 Paintings, paper, objects, furniture, P: 413/458.5741 sculpture, frames, analytical F: 413/458.2314 Email: [email protected] Website: www.williamstownart.org Worcester Art Museum 55 Salisbury Street Worcester, MA 01609 Paper, Paintings P: 508/799.4406 Email: [email protected] Website: www.worcesterart.org CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015 General Continued Art Conservation Resource Center 262 Beacon Street, #4 Paintings, paper, photographs, textiles, Boston, MA 02116 objects and sculpture P: -

Conservation of Cultural and Scientific Objects

CHAPTER NINE 335 CONSERVATION OF CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC OBJECTS In creating the National Park Service in 1916, Congress directed it "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life" in the parks.1 The Service therefore had to address immediately the preservation of objects placed under its care. This chapter traces how it responded to this charge during its first 66 years. Those years encompassed two developmental phases of conservation practice, one largely empirical and the other increasingly scientific. Because these tended to parallel in constraints and opportunities what other agencies found possible in object preservation, a preliminary review of the conservation field may clarify Service accomplishments. Material objects have inescapably finite existence. All of them deteriorate by the action of pervasive external and internal agents of destruction. Those we wish to keep intact for future generations therefore require special care. They must receive timely and. proper protective, preventive, and often restorative attention. Such chosen objects tend to become museum specimens to ensure them enhanced protection. Curators, who have traditionally studied and cared for museum collections, have provided the front line for their defense. In 1916 they had three principal sources of information and assistance on ways to preserve objects. From observation, instruction manuals, and formularies, they could borrow the practices that artists and craftsmen had developed through generations of trial and error. They might adopt industrial solutions, which often rested on applied research that sought only a reasonable durability. And they could turn to private restorers who specialized in remedying common ills of damaged antiques or works of art. -

4-10 Matting and Framing.Pdf

PRESERVATION LEAFLET CONSERVATION PROCEDURES 4.10 Matting and Framing for Works on Paper and Photographs NEDCC Staff NEDCC Andover, MA The importance of proper matting, mounting and framing Do not use any type of foam board such as Fom-cor®, is often overlooked as a key part of collections care and “archival” paper faced foam boards, Gator board, preventative conservation. Poor quality materials and expanded PVC boards such as Sintra® or Komatex®, any improper framing techniques are a common source of lignin containing paper-based mat boards, kraft (brown) damage to artwork and cultural heritage materials that paper, non-archival or self-adhesive tapes (i.e. document are in otherwise good condition. Staying informed about repair tapes), or ATG (adhesive transfer gum), all of which proper framing practices and choosing conservation-grade are used in the majority of frame shops. mounting, matting and framing can prevent many problems that in the future will be much more difficult to MATTING solve or even completely irreversible. As Benjamin Franklin said, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of The window mat is the standard mount for works on cure.” paper. The ideal window mat will be aesthetically pleasing while safely protecting the piece from exterior damage. Mats are an excellent storage method for works on paper CHOICE OF A FRAMER and can minimize the damage caused from handling in When choosing a framer it is important to find someone collections that are used for exhibition and study. Some well-informed about best conservation framing practices institutions simplify their framing and storage operations and experienced in implementing them. -

QAR Field Operations – May 2005

QAR Field Operations – October 2006 Artifact Conservation & Documentation Sarah Watkins-Kenney – QAR Project Chief Conservator Wendy Welsh—QAR Assistant Conservator I. Personnel: At least two members of the QAR Conservation & Documentation (C&D) team will be on site for each day of field operations. C&D Team: Sarah Watkins-Kenney (SWK) QAR Project Chief Conservator Wendy Welsh (WMW) QAR Assistant Conservator/(C&D Field Team Leader) Valerie Grussing (VJG) QAR Conservation Technician Franklin Price (FHP) Underwater Archaeology Technician Anne Corscadden-Knox (ACK) Underwater Archaeology Technician Steve Lambert (S L) Underwater Archaeology Technician Johnny Masters (JPM) Underwater Archaeology Technician Linda Carnes McNaughton (LCMN) Volunteer, Historian/Conservation assistant III. Documentation ON SITE includes: i TAGS- - Mylar or Tyvek are available from C&D team. - Must be tied to all artifact/concretions with cable ties so that tag lies on top surface as in situ. Provenance E & N taken to tag. - QAR# marked in industrial permanent black marker on both sides of the tag – while tag dry. For Fall 2006 – tags will be pre-numbered. - Additional information -marked in pencil (both types of tag can be written on with pencil underwater). - Information that must be on each tag, attached to artifacts, before they are brought to the surface: QAR#. - Additional information to be put on tag (either by field C&D or lab based C&D), Unit number in circle, E, N provenance, diver initials, date recovered. - For ballast, dredge/sieve material – one tag should be place inside bag and one tied to outside of container as appropriate. ii BAG & CONTAINER LABELS - - Each bag should be marked on outside, in permanent marker, with Unit #, E&N provenance, QAR#. -

Integrating Archaeology and Conservation of Archaeology and Conservation the Past, Forintegrating the Future

SC 13357-2 11/30/05 2:39 PM Page 1 PROCEEDINGS PROCEEDINGS The Getty Conservation Institute The Conservation Los Angeles Theme of the 5th World Archaeological Congress Of the Past, for the Future: Washington, D.C. Printed in Canada June 2003 Integrating Archaeology and Conservation Of the Past, for the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation The Getty Conservation Institute i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page i Of the Past, for the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page ii i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page iii Of the Past, for the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation Proceedings of the Conservation Theme at the 5th World Archaeological Congress, Washington, D.C., 22–26 June 2003 Edited by Neville Agnew and Janet Bridgland The Getty Conservation Institute Los Angeles i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page iv The Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, Director Jeanne Marie Teutonico, Associate Director, Field Projects and Science The Getty Conservation Institute works internationally to advance conserva- tion and to enhance and encourage the preservation and understanding of the visual arts in all of their dimensions—objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research; education and training; field projects; and the dissemination of the results of both its work and the work of others in the field. In all its endeavors, the Institute is committed to addressing unanswered questions and promoting the highest possible standards of conservation practice. -

LARA KAPLAN 5105 Kennett Pike OBJECTS CONSERVATOR Winterthur, DE 19735 [email protected]

Winterthur Museum LARA KAPLAN 5105 Kennett Pike Winterthur, DE 19735 OBJECTS CONSERVATOR [email protected] EDUCATION Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, Winterthur, DE M.S./Certificate in Art Conservation, objects major – August 2003 Rice University, Houston, TX B.A. Art/Art History and Linguistics, cum laude – May 1997 CONSERVATION EXPERIENCE 7/19-Present: Objects Conservator; Affiliated Assistant Professor Winterthur Museum, Library and Gardens; Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC) – Winterthur, DE At Winterthur, preserving three-dimensional objects in the museum collection, conducting technical examinations and treatment, and consulting on proper handling, storage, transport, and exhibition requirements. For WUDPAC, leading the Organic Block portion of the 1st-year curriculum, covering plant materials, skin/leather, keratins, ivory, bone, and related materials, and plastics; supervising 2nd- and 3rd-year objects majors; serving on student advisory committees; teaching advanced seminars on specialized topics, including characterization and treatment of skin/leather artifacts, conservation of basketry, feathers, and plastics, ethical issues in the conservation of modern/contemporary collections and objects from indigenous cultures, and opening a conservation private practice. 1/05-Present: Freelance Conservator Baltimore, MD (1/05-12/18); Philadelphia, PA (1/19-Present) Working as an independent conservator for institutions, galleries, and private individuals. Services include examination, treatment, surveys, art historical research, and sampling/testing of art and artifacts made of a wide range of materials (glass, ceramics, stone, plaster, metals, lacquer, wood and other plant materials, skin and leather, horn, tortoiseshell, feather, ivory, bone, shell, rubber, and plastics), as well as consultation and preparing objects for storage, transportation, and exhibition. -

MCI Interns and Volunteers

MCI Weekly Highlight 13 August 2010 Understanding the American Experience, Valuing World Cultures , Unlocking the Mysteries of the Universe, Understanding and Sustaining a Biodiverse Planet The Museum Conservation Institute hosted 10 interns and volunteers this summer. These individuals significantly increase research and conservation treatment productivity at MCI. We would like to take the opportunity to acknowledge their contributions and wish them the best in their future endeavors. • In the Paintings Conservation Laboratory under the mentorship of Senior Paintings Conservator, Jia-sun Tsang, Laura King worked on Sam Gilliam’s Muse I from 1965 which is a stained acrylic painting, and James Aiken’s Swedish Cottage and Shakespeare Garden from 1959 which is an oil painting—both paintings from the Anacostia Community Museum. Allison Martin continued to work with Jia-sun Tsang on several paintings conservation-related projects. Rebecca Gieseking worked with Jia-sun on a manuscript based on a plastics conservation project that they began two years ago. • E. Keats Webb worked with Senior Conservator, Mel Wachowiak, on an in-depth exploration of 3D scanning, Quick Time Virtual Reality, High Definition digital video, and Reflectance Transformation Imaging. A publication is pending that will compare the strengths and weaknesses of the techniques in cultural heritage applications. • In the Textile Conservation Studio, Mary Ballard, Senior Textiles Conservator, oversaw the work of several intern projects focusing on the Black Fashion Museum collection acquired by the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Cathleen Zaret finished re-housing the McGee collection of garments,and will turn to repairs on a lovely honeymoon peignoir as she finishes her internship August 30. -

Three Basic Book Repair Procedures - 1 | Back

Three Basic Book Repair Procedures - 1 | Back By Carole Dyal and Pete Merrill-Oldham Introduction Hinge Tightening I Hinge Tightening II Tipping-In Loose Pages Conclusions - References In libraries large and small, minor repair is a critical component in overall efforts to care for collections of books and journals. Bound volumes mended as soon as they show signs of damage may never require more complex repair or binding. A book with tightened hinges is sometimes more sturdy after treatment than it was at the time of purchase. Following are instructions for carrying out three basic cost-effective procedures for repairing hard-cover volumes. They were prepared to accompany all- day demonstrations presented at the 1998 Annual Meeting of the American Library Association in Washington, DC. The Library of Congress generously offered space in the LC exhibit booth in support of this pilot project. It focuses on early intervention as a means of delaying or eliminating the need for more time consuming and expensive treatment. This project was made possible through generous support from Acme Bookbinding (Charlestown, MA), Bridgeport National Bindery (Agawam, MA), Conservation Resources International (Springfield, VA), Gaylord Bros. (Syracuse, NY), Information Conservation Incorporated and the Etherington Conservation Center (Brown Summit, NC), the Library Binding Institute (Edina, MN), Library Binding Service (Des Moines, IA), Ocker & Trapp Library Bindery (Emerson, NJ), SOLINET (Atlanta, GA), and University Products (Holyoke, MA). Hinge Tightening I Inspect the hinge of the volume at the head and tail to see if the text block has become loose in its case. If the endpapers are pulling away from the inside of the case but are still securely attached to the text block, Hinge Tightening I may be an appropriate treatment. -

Conservation Technician Associate Conservator

POSITION DATA JOB TITLE: Conservation Technician DEPARTMENT: Collections REPORTS TO: Associate Conservator CLASSIFICATION: Nonexempt DATE: August 2021 POSITION OVERVIEW: The National September 11 Memorial & Museum seeks a Conservation Technician (CT) to serve as a ‘hands-on’ collections-care provider in the public spaces and storage areas of the Museum. The CT’s responsibilities will primarily support preventive conservation efforts at the Museum, working primarily with physical objects in the collection but supporting stewardship of the Museum’s accessioned digital assets. The CT will assist in the safe handling/transit, storage, exhibition and outgoing loan preparation, and routine maintenance of objects in the collection. The scope of these holdings is diverse in medium, scale, type, and inherent condition, and includes material evidence, memorial and tribute items, artwork, historical records, and web- based artifacts relating to the terrorist attacks of February 26, 1993, and September 11, 2001, and their repercussions. The incumbent reports to the Museum’s Associate Conservator. Work will generally take place during standard business hours. However, with advance notice, schedules may be adjusted to accommodate special projects which involve early morning or evening hours. Comprehensive training will be provided to familiarize the CT with the Museum’s equipment, software, art handling and PPE protocols and other collection policies. ESSENTIAL FUNCTIONS • Maintains and cleans open mount artifacts in the Museum’s exhibition spaces and monitors for any changes in condition. • Locates and moves objects to/from the Museum’s storage spaces and update locations in Collective Access, its collections management system. • Assists with preventive conservation activities including monitoring and collecting environmental data using data loggers and liaising with the Museum’s Integrated Pest Management vendor. -

Curation Standards and Procedures, As Amended

COUNCIL OF TEXAS ARCHEOLOGISTS GUIDELINES AND STANDARDS FOR CURATION Prepared by the Curation Committee Revised Spring 2020 COUNCIL OF TEXAS ARCHEOLOGISTS - GUIDELINES AND STANDARDS FOR CURATION CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 2 GUIDELINES FOR SUBMITTING COLLECTIONS FOR CURATION .................................... 2 2.1 Pre-Curation Field Strategies ........................................................................................................ 2 2.1.1 Excavation and Field Conservation .................................................................................... 3 2.2 Arranging for Curation with an Archeological Repository .......................................................... 5 2.2.1 Letter of Request for Housing ............................................................................................. 5 2.2.2 Letter of Transfer/Ownership ............................................................................................. 6 2.2.3 Letter of Acceptance ........................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Standards for Preparing Archeological Records ........................................................................... 7 2.3.1 Guidelines for Environmental Conditions by Material Type (adapted from NPS Museum Handbook, Part I [NPS 2019b]) ........................................................................... 8 2.3.2