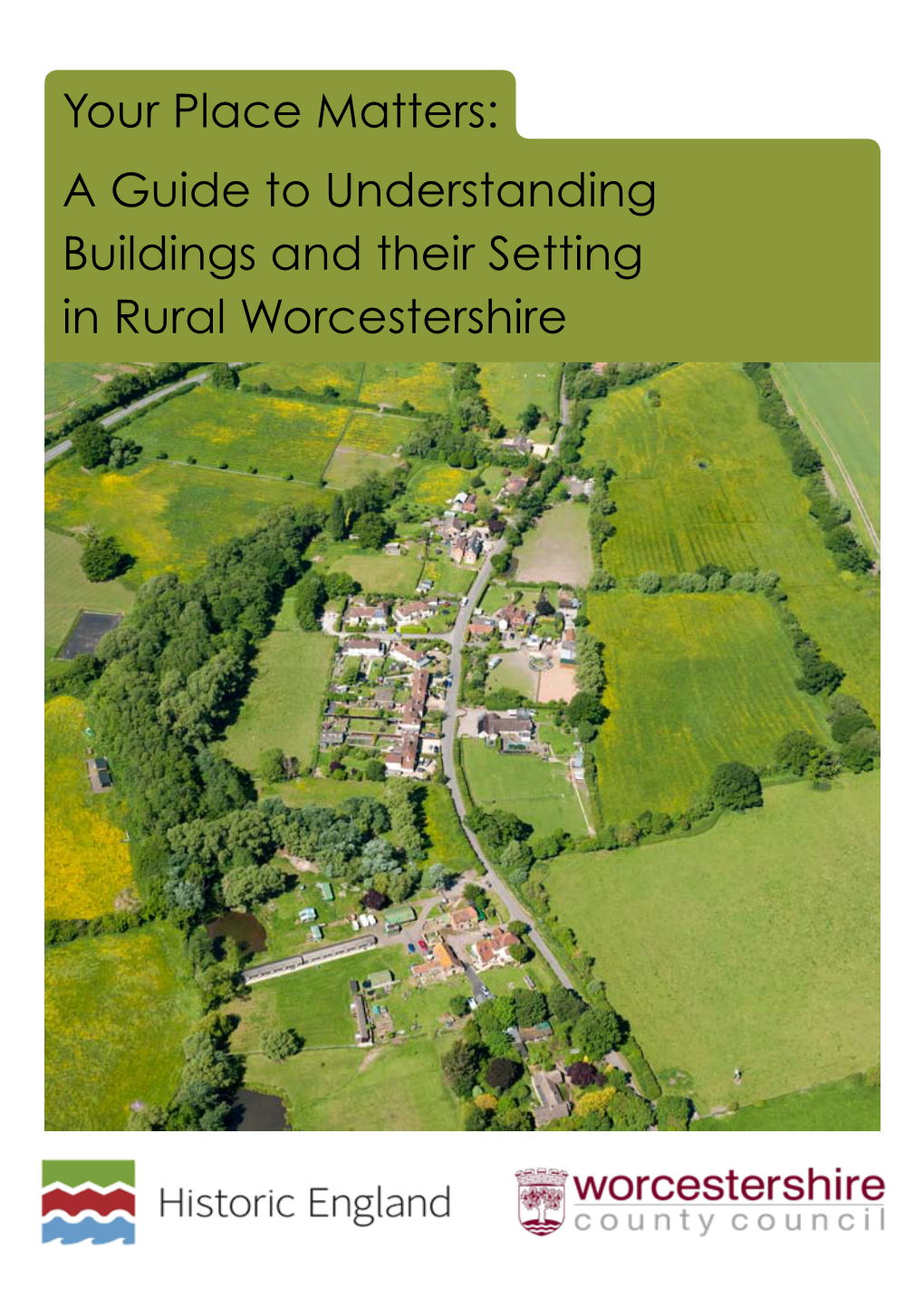

Your Place Matters, a Guide to Understanding Buildings and Their

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shropshire Council HER: Monument Full Report 04/10/2019 Number of Records: 99

Shropshire Council HER: Monument Full Report 04/10/2019 Number of records: 99 HER Number Site Name Record Type 01035 Bradling Stone Monument This site represents: a non antiquity of unknown date. Monument Types and Dates NON ANTIQUITY (Unknown date) Evidence NATURAL FEATURE Description and Sources Description A possible chamber tomb <1> At Norton in Hales, are some remains which undoubtedly once formed part of a burial chamber <2a> A large stone standing on the green between the church and an inn associated with a Shrove Tuesday custom of great antiquity <2b> 0220In a plantation, (SJ30343861), formerly stood under a tree on the village green. Stone is natural and not an antiquity <2c> Roughly triangular stone with 1.8m sides and 0.5m thick. It is mounted on three smaller stones on the village green. OS FI 1975 <2> Sources (00) Card index: Site and Monuments Record (SMR) cards (SMR record cards) by Shropshire County Council SMR, SMR Card for PRN SA 01035. Location: SMR Card Drawers (01) Index: Print out by Birmingham University. Location: not given (02) Card index: Ordnance Survey Record Card SJ73NW14 (Ordnance Survey record cards) by Ordnance Survey (1975). Location: SMR OSRC Card Drawers (02a) Volume: Antiquity (Antiquity) by Anon (1927), p29. Location: not given (02b) Monograph: The History and Description of The County of Salop by Hulbert C (1837), p116. Location: not given (02c) Map annotation: Map annotation (County Series) by Anon. Location: Shropshire Archives Location National Grid Reference Centred SJ 7032 3864 (10m by 10m) SJ73NW -

FARNDON 'Tilstone Fearnall' 1970 'Tiverton' 1971

Earlier titles in this series of histories of Cheshire villages are:— 'Alpraham' 1969 FARNDON 'Tilstone Fearnall' 1970 'Tiverton' 1971 By Frank A. Latham. 'Tarporley' 1973 'Cuddington & Sandiway' 1975 'Tattenhall' 1977 'Christleton' 1979 The History of a Cheshire Village By Local History Groups. Edited by Frank A. Latham. CONTENTS Page FARNDON Foreword 6 Editor's Preface 7 PART I 9 An Introduction to Farndon 11 Research Organiser and Editor In the Beginning 12 Prehistory 13 FRANK A. LATHAM The Coming of the Romans 16 The Dark Ages 18 The Local History Group Conquest 23 MARIE ALCOCK Plantagenet and Tudor 27 LIZ CAPLIN Civil War 33 A. J. CAPLIN The Age of Enlightenment 40 RUPERT CAPPER The Victorians 50 HAROLD T. CORNES Modern Times JENNIFER COX BARBARA DAVIES PART II JENNY HINCKLEY Church and Chapel 59 ARTHUR H. KING Strawberries and Cream 66 HAZEL MORGAN Commerce 71 THOMAS W. SIMON Education 75 CONSTANCE UNSWORTH Village Inns 79 HELEN VYSE MARGARET WILLIS Sports and Pastimes 83 The Bridge 89 Illustrations, Photographs and Maps by A. J. CAPLIN Barnston of Crewe Hill 93 Houses 100 Natural History 106 'On Farndon's Bridge' 112 Published by the Local History Group 1981 and printed by Herald Printers (Whitchurch) Ltd., Whitchurch, Shropshire. APPENDICES Second Edition reprinted in 1985 113 ISBN 0 901993 04 2 Hearth Tax Returns 1664 Houses and their Occupants — The Last Hundred Years 115 The Incumbents 118 The War Memorial 119 AH rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, The Parish Council 120 electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the editor, F. -

Caerfallen, Ruthin LL15 1SN

Caerfallen, Ruthin LL15 1SN Researched and written by Zoë Henderson Edited by Gill. Jones & Ann Morgan 2017 HOUSE HISTORY RESEARCH Written in the language chosen by the volunteers and researchers & including information so far discovered PLEASE NOTE ALL THE HOUSES IN THIS PROJECT ARE PRIVATE AND THERE IS NO ADMISSION TO ANY OF THE PROPERTIES ©Discovering Old Welsh Houses Group [North West Wales Dendrochronolgy Project] Contents page no. 1. The Name 2 2. Dendrochronology 2 3. The Site and Building Description 3 4. Background History 6 5. 16th Century 10 5a. The Building of Caerfallen 11 6. 17th Century 13 7. 18th Century 17 8. 19th Century 18 9. 20th Century 23 10. 21st Century 25 Appendices 1. The Royal House of Cunedda 29 2. The De Grey family pedigree 30 3. The Turbridge family pedigree 32 4. Will of John Turbridge 1557 33 5. The Myddleton family pedigree 35 6. The Family of Robert Davies 36 7. Will of Evan Davies 1741 37 8. The West family pedigree 38 9. Will of John Garner 1854 39 1 Caerfallen, Ruthin, Denbighshire Grade: II* OS Grid Reference SJ 12755 59618 CADW no. 818 Date listed: 16 May 1978 1. The Name Cae’rfallen was also a township which appears to have had an Isaf and Uchaf area which ran towards Llanrydd from Caerfallen. Possible meanings of the name 'Caerfallen' 1. Caerfallen has a number of references to connections with local mills. The 1324 Cayvelyn could be a corruption of Caevelyn Field of the mill or Mill field. 2. Cae’rafallen could derive from Cae yr Afallen Field of the apple tree. -

10–14 Churchgate: Hallaton's Lost Manor House?

12 10–14 Churchgate: Hallaton’s Lost Manor House? Nick Hill This building, a high quality timber-framed structure dating to the late fifteenth century, has been the subject of a recent programme of detailed recording and analysis, accompanied by dendrochronology. It is located on a prominent site, just opposite the church, at the centre of the village of Hallaton in south-east Leicestershire (OS ref: SP787966). The building, of six bays, had timber-framed walls with heavy close-studding throughout. Three bays originally formed an open hall, with a high arch-braced roof truss of an unusual ‘stub tie beam’ form, a rare Midlands type associated with high status houses. Although this was an open hall, the absence of smoke blackening indicates that there must have been a chimneystack from the beginning rather than an open hearth, an unusually early feature for the late fifteenth century. The whole timber-framed structure is of sophisticated, high class construction, and contrasts strongly with other houses of the period in the village, which are cruck-built. It is suggested that, though subsequently reduced in status and subdivided into four cottages, it was once one of the two main manor houses of Hallaton. The location of this second manor house has been lost since it was merged with the other main manor in the early seventeenth century. Introduction The pair of cottages, now known as 10/12 and 14 Churchgate, stands on a corner site, at the junction of Churchgate with Hunts Lane, immediately to the north-east of Hallaton church. Externally, the building has few features of interest, with cement-rendered walls under a thatched roof (illus. -

{PDF} the New Timber-Frame Home: Design, Construction and Finishing

THE NEW TIMBER-FRAME HOME: DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION AND FINISHING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tedd Benson | 240 pages | 03 Jan 1998 | Taunton Press Inc | 9781561581290 | English | Connecticut, United States The Timber-Frame Home by Tedd Benson - Home Design - Design Guides - Hardcover Book If you can reduce the number of timbers used in your home, it can yield a nice savings to your budget. We design and craft many hybrid homes now. In fact, these hybrid homes have become more common than fully timber-framed homes. How you plan to finish your new timber frame home is perhaps the biggest unknown variable. One good thing about interior finishes is that it is more controllable. Again, this percentage can easily go up or down depending on your choices. As you can tell, there are a lot of components that go into building a new home and much of the overall cost to build a new home, a timber frame, will be dependent upon your choices in the design of your home and interior finishes. Interested in learning more about planning and budgeting your timber frame home? Call us today at Big Ticket Budget Items to Consider: Land This home site in Connecticut needed major blasting, adding a huge chunk to the overall budget. Design Complexity A complex home design is shown in this picture. Hybrid VS. Full Timber Frame Example of a hybrid timber frame home. Interior Finishings How you plan to finish your new timber frame home is perhaps the biggest unknown variable. Share on Facebook Share. Perhaps the most critical part of planning to build a timber frame home is to determine what your overall budget is. -

Agenda Reports Pack (Public) 24/11/2010, 14.00

Public Document Pack Southern Planning Committee Agenda Date: Wednesday, 24th November, 2010 Time: 2.00 pm Venue: Council Chamber, Municipal Buildings, Earle Street, Crewe CW1 2BJ Members of the public are requested to check the Council's website the week the Southern Planning Committee meeting is due to take place as Officers produce updates for some or all of the applications prior to the commencement of the meeting and after the agenda has been published. The agenda is divided into 2 parts. Part 1 is taken in the presence of the public and press. Part 2 items will be considered in the absence of the public and press for the reasons indicated on the agenda and at the foot of each report. PART 1 – MATTERS TO BE CONSIDERED WITH THE PUBLIC AND PRESS PRESENT 1. Apologies for Absence To receive apologies for absence. 2. Declarations of Interest/Pre-Determination To provide an opportunity for Members and Officers to declare any personal and/or prejudicial interests and for Members to declare if they have pre-determined any item on the agenda. 3. Minutes of Previous Meeting (Pages 1 - 8) To approve the minutes of the meeting held on 3 November 2010. 4. Public Speaking A total period of 5 minutes is allocated for each of the planning applications for Ward Councillors who are not Members of the Planning Committee. Please contact Julie Zientek on 01270 686466 E-Mail: [email protected] with any apologies, requests for further information or to arrange to speak at the meeting A period of 3 minutes is allocated for each of the planning applications for the following individual groups: • Members who are not members of the Planning Committee and are not the Ward Member • The Relevant Town/Parish Council • Local Representative Groups/Civic Society • Objectors • Supporters • Applicants 5. -

Agenda Reports Pack (Public) 21/12/2011, 10.30

Public Document Pack Strategic Planning Board Agenda Date: Wednesday, 21st December, 2011 Time: 10.30 am – PLEASE NOTE THIS IS A CHANGE OF START TIME FROM THE ORIGINALLY ADVERTISED TIME OF 2.00 PM Venue: Meeting Room, Macclesfield Library, Jordangate, Macclesfield, SK10 1EE Members of the public are requested to check the Council's website the week the Strategic Planning Board meeting is due to take place as Officers produce updates for some or all of the applications prior to the commencement of the meeting and after the agenda has been published. The agenda is divided into 2 parts. Part 1 is taken in the presence of the public and press. Part 2 items will be considered in the absence of the public and press for the reasons indicated on the agenda and at the foot of each report. Please note the original order of items has been changed and the sequence will be as follows : PART 1 – MATTERS TO BE CONSIDERED WITH THE PUBLIC AND PRESS PRESENT Morning Session 1. Apologies for Absence To receive any apologies for absence. 2. Declarations of Interest To provide an opportunity for Members and Officers to declare any personal and/or prejudicial interests and for Members to declare if they have a pre-determination in respect of any item on the agenda. For any apologies or requests for further information, or to arrange to speak at the meeting Contact : Gaynor Hawthornthwaite Tel: 01270 686467 E-Mail: [email protected] 3. Minutes of the Previous Meeting (Pages 1 - 6) To approve the minutes of the meeting held on 29 th November 2011 as a correct record. -

The Stour Valley Heritage Compendia the Built Heritage Compendium

The Stour Valley Heritage Compendia The Built Heritage Compendium Written by Anne Mason BUILT HERITAGE COMPENDIUM Contents Introduction 5 Background 4 High Status Buildings 5 Churches of the Stour Valley and Dedham Vale 6 Vernacular Buildings 11 The Vernacular Architecture of the Individual Settlements of the Stour Valley and Dedham Vale 18 Conclusion: The Significance of the Built Heritage of the Stour Valley and Dedham Vale 42 Archival Sources for the Built Heritage 43 Bibliography 43 Glossary 44 2 Introduction Buildings are powerful and evocative symbols in the landscape, showing how people have lived and worked in the past. They can be symbols of authority; of opportunity; of new technology, of social class and fluctuations in the local, regional and national economy. Traditional buildings make a major contribution to understanding about how previous generations lived and worked. They also contribute to local character, beauty and distinctiveness as well as providing repositories of local skills and building techniques. Historic buildings are critical to our understanding of settlement patterns and the development of the countryside. Hardly any buildings are as old as the history of a settlement because buildings develop over time as they are extended, rebuilt, refurbished or decay. During the Roman period the population of the Stour Valley increased. The majority of settlements are believed to have been isolated farmsteads along the river valley and particularly at crossing points of the Stour. During the Saxon and medieval periods many of the settlement and field patterns were formed and farmsteads established whose appearance and form make a significant contribution to the landscape character of the Stour Valley. -

Framlingham Conservation Area Appraisal

FRAMLINGHAM CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL December 2013 On 1 April 2019, East Suffolk Council was created by parliamentary order, covering the former districts of Suffolk Coastal District Council and Waveney District Council. The Local Government (Boundary Changes) Regulations 2018 (part 7) state that any plans, schemes, statements or strategies prepared by the predecessor council should be treated as if i t had been prepared and, if so required, published by the successor council - therefore this document continues to apply to East Suffolk Council until such time that a new document is published. Bibliography Alexander, Magnus. Framlingham Castle, Suffolk: The Landscape Context, English Heritage Research Department Report No 106-2007. (London, 2007) Bridges, John F. Framlingham, Portrait of a Suffolk Town (Long Melford, 1975) Bridges, John F. The Commercial Life of a Suffolk Town, Framlingham around 1900, (Cromer, 2007) Brodie, A & Felstead A. Directory of British Architects 1834-1914 (London, 2001) English Heritage. The National Heritage List for England – Website http://list.english-heritage.org.uk/ English Heritage. Understanding Place: Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management (London, 2011) Framlingham and District Local History and Preservation Society, Fram: The Journal of the Framlingham and District Local History and Preservation Society (Framlingham) Framlingham and District Local History and Preservation Society – Website http://framlinghamarchive.org.uk/about/ Hawes, Robert & Loder, Robert. The History of Framlingham in the County of Suffolk (Woodbridge, 1798) Kilvert, Muriel L. A History of Framlingham, (Ipswich, 1995) Mc Ewan, John. Lambert’s Framlingham 1871-1916, (Framlingham, 2000) Pevsner N & Radcliffe E. The Buildings of England, Suffolk (Harmondsworth, 2000) Sandon, Eric. Suffolk Houses, A Study of Domestic Architecture (Woodbridge, 2003) Stacey, Nichola. -

Tree-Ring Dates

Tree-ring dated roofs VAG © 2021 INDEX OF TREE-RING DATED BUILDINGS IN ENGLAND NATIONAL LIST approximately in chronological order, revised to VA51 (2020). © Vernacular Architecture Group 2021 These files may be copied for personal use, but should not be published or further distributed without written permission from the Vernacular Architecture Group. Always access these tables via the VAG website. Unauthorised copies released without prior consent on search engines may be out of date and unreliable. Since 2016 a very small number of construction date ranges from historical sources have been added. These entries are entirely in italics. Before using the index you are recommended to read or print the introduction and guidance, which includes a key to the abbreviations used on the tables. 1550 -1599 Place Felling date County- Placename Address VA ref; HE ref; Description / keywords NGR holder range historic (other ref) (later) 1550 1536 -63 ? Cumb Heslington Sizergh Castle 31.120 Sh Rural. Stone. Pele tower. This date is for roof. (Also see 1530 -64). SD 499879 1550 1537 -62 Derbs Dronfield 7 -12 Church Street 46.98 Notm Agricultural bldg., now stone. Cruck trusses C, D and E. (For cruck trusses A & B SK 353783 RRS 55/2014 see 1450s to 1460s) 1550 1550 c. Dors Toller Fratrum Little Toller 48.95 Notm Stone main range. Fire-damaged roof – coupled rafters, collars, arch-braces [i.e. SY 578947 Farmhouse RRS 30-2016 wagon roof]. 1550 1527 -72 Ess Abbess Roding Rookwood Hall 24.50 MoL Maltings. No roof details. TL 562111 1550 1549 /50 Hamps Froxfield Trees Cottage 23.48 Oxf Rebuilt service end. -

Bramall Hall & Park Conservation Management Plan

DONALD INSALL ASSOCIATES Chartered Architects, Historic Building & Planning Consultants BRAMALL HALL, STOCKPORT Conservation Management Plan September 2010 BRAMALL HALL Conservation Management Plan This page has been left blank intentionally Donald Insall Associates Ltd STBH.03 c.002 Final Version – September 2010 BRAMALL HALL Conservation Management Plan BRAMALL HALL CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN for STOCKPORT METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL Prepared by Donald Insall Associates Ltd. Bridgegate House 5 Bridge Place Chester CH1 1SA Tel. 01244 350063 Fax. 01244 350064 www.insall-architects.co.uk SEPTEMBER 2010 Donald Insall Associates Ltd i STBH.03 c.002 Final Version – September 2010 BRAMALL HALL Conservation Management Plan This page has been left blank intentionally Donald Insall Associates Ltd STBH.03 c.002 Final Version –September 2010 BRAMALL HALL Conservation Management Plan BRAMALL HALL CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................1 1.1 Background to the Plan ...............................................................................................1 1.2 Production of the Plan and Copyright .........................................................................1 1.3 The Site Location, its Setting and Notes on Orientation .............................................2 1.4 General Purpose and Scope of the Plan.......................................................................2 1.5 Structure -

Vernacular Houses Listing Selection Guide Summary

Domestic 1: Vernacular Houses Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of- selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. This guide, one of four on different types of Domestic Buildings, covers vernacular houses, that is dwellings erected mainly before the Victorian period when increasing standardisation of materials and design became widespread.