Shrewbury: Topography and Domestic Architecture to the Middle of the Seventeenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shropshire Council HER: Monument Full Report 04/10/2019 Number of Records: 99

Shropshire Council HER: Monument Full Report 04/10/2019 Number of records: 99 HER Number Site Name Record Type 01035 Bradling Stone Monument This site represents: a non antiquity of unknown date. Monument Types and Dates NON ANTIQUITY (Unknown date) Evidence NATURAL FEATURE Description and Sources Description A possible chamber tomb <1> At Norton in Hales, are some remains which undoubtedly once formed part of a burial chamber <2a> A large stone standing on the green between the church and an inn associated with a Shrove Tuesday custom of great antiquity <2b> 0220In a plantation, (SJ30343861), formerly stood under a tree on the village green. Stone is natural and not an antiquity <2c> Roughly triangular stone with 1.8m sides and 0.5m thick. It is mounted on three smaller stones on the village green. OS FI 1975 <2> Sources (00) Card index: Site and Monuments Record (SMR) cards (SMR record cards) by Shropshire County Council SMR, SMR Card for PRN SA 01035. Location: SMR Card Drawers (01) Index: Print out by Birmingham University. Location: not given (02) Card index: Ordnance Survey Record Card SJ73NW14 (Ordnance Survey record cards) by Ordnance Survey (1975). Location: SMR OSRC Card Drawers (02a) Volume: Antiquity (Antiquity) by Anon (1927), p29. Location: not given (02b) Monograph: The History and Description of The County of Salop by Hulbert C (1837), p116. Location: not given (02c) Map annotation: Map annotation (County Series) by Anon. Location: Shropshire Archives Location National Grid Reference Centred SJ 7032 3864 (10m by 10m) SJ73NW -

Besford Gardens, Trinity Street, Belle Vue, Shrewsbury, SY3 7PQ

ESTATE & LETTINGS AGENTS | CHARTERED SURVEYORS HOW TO FIND THIS PROPERTY From the town centre, the development is best approached over the English Bridge and around the gyratory system into Coleham Head. Continue along Belle Vue Road, eventually turning left into Trinity Street. Continue to the top of Trinity Street and Besford Gardens will be found on the right hand side. SERVICES We understand that mains water, electricity, drainage and natural gas are connected. In partnership with Floreat Homes TENURE We are advised that the properties are freehold and this will be confirmed by the vendors' solicitors during pre-contract enquiries LOCAL AUTHORITIES Shropshire Council Frankwell, Shrewsbury Tel 0345 678 9000 2014-05-23 IMPORTANT NOTICE Our particulars have been prepared with care and are checked where possible by the vendor. They are however, intended as a guide. Measurements, areas and distances are approximate. Appliances, plumbing, heating and electrical fittings are noted, but not tested. Legal matters including Rights of Way, Covenants, Easements, Wayleaves and Planning matters have not been verified and you should take advice from your legal representatives and Surveyor. DO YOU HAVE A PROPEPROPERTYRTY TO SELL ??? We will always be pleased to give you a no obligation market assessment of your existing property to help you with your decision to move DO YOU NEED A SURVEYOR ? We are Chartered Surveyors and will be pleased to give advice on Surveys, Homebuyers Reports and other professional matters. Besford Gardens, Trinity Street, Belle Vue, Shrewsbury, SY3 7PQ To view this property please call us on 01743 236800 Ref: T 4971/SL/GA 3 Bedroomed, Semi-detached House Besford Gardens is an attractive development of 11 houses, set in the popular and established conservation area of Belle Vue. -

Accounts of the Constables of Bristol Castle

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A., Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M .A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXIV ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN 1HE THIRTEENTH AND EARLY FOURTEENTH CENTURIES ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN THE THIR1EENTH AND EARLY FOUR1EENTH CENTURIES EDITED BY MARGARET SHARP Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1982 ISSN 0305-8730 © Margaret Sharp Produced for the Society by A1an Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Limited Trowbridge CONTENTS Page Abbreviations VI Preface XI Introduction Xlll Pandulf- 1221-24 1 Ralph de Wiliton - 1224-25 5 Burgesses of Bristol - 1224-25 8 Peter de la Mare - 1282-84 10 Peter de la Mare - 1289-91 22 Nicholas Fermbaud - 1294-96 28 Nicholas Fermbaud- 1300-1303 47 Appendix 1 - Lists of Lords of Castle 69 Appendix 2 - Lists of Constables 77 Appendix 3 - Dating 94 Bibliography 97 Index 111 ABBREVIATIONS Abbrev. Plac. Placitorum in domo Capitulari Westmon asteriensi asservatorum abbrevatio ... Ed. W. Dlingworth. Rec. Comm. London, 1811. Ann. Mon. Annales monastici Ed. H.R. Luard. 5v. (R S xxxvi) London, 1864-69. BBC British Borough Charters, 1216-1307. Ed. A. Ballard and J. Tait. 3v. Cambridge 1913-43. BOAS Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Transactions (Author's name and the volume number quoted. Full details in bibliography). BIHR Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. BM British Museum - Now British Library. Book of Fees Liber Feodorum: the Book of Fees com monly called Testa de Nevill 3v. HMSO 1920-31. Book of Seals Sir Christopher Hatton's Book of Seals Ed. -

FARNDON 'Tilstone Fearnall' 1970 'Tiverton' 1971

Earlier titles in this series of histories of Cheshire villages are:— 'Alpraham' 1969 FARNDON 'Tilstone Fearnall' 1970 'Tiverton' 1971 By Frank A. Latham. 'Tarporley' 1973 'Cuddington & Sandiway' 1975 'Tattenhall' 1977 'Christleton' 1979 The History of a Cheshire Village By Local History Groups. Edited by Frank A. Latham. CONTENTS Page FARNDON Foreword 6 Editor's Preface 7 PART I 9 An Introduction to Farndon 11 Research Organiser and Editor In the Beginning 12 Prehistory 13 FRANK A. LATHAM The Coming of the Romans 16 The Dark Ages 18 The Local History Group Conquest 23 MARIE ALCOCK Plantagenet and Tudor 27 LIZ CAPLIN Civil War 33 A. J. CAPLIN The Age of Enlightenment 40 RUPERT CAPPER The Victorians 50 HAROLD T. CORNES Modern Times JENNIFER COX BARBARA DAVIES PART II JENNY HINCKLEY Church and Chapel 59 ARTHUR H. KING Strawberries and Cream 66 HAZEL MORGAN Commerce 71 THOMAS W. SIMON Education 75 CONSTANCE UNSWORTH Village Inns 79 HELEN VYSE MARGARET WILLIS Sports and Pastimes 83 The Bridge 89 Illustrations, Photographs and Maps by A. J. CAPLIN Barnston of Crewe Hill 93 Houses 100 Natural History 106 'On Farndon's Bridge' 112 Published by the Local History Group 1981 and printed by Herald Printers (Whitchurch) Ltd., Whitchurch, Shropshire. APPENDICES Second Edition reprinted in 1985 113 ISBN 0 901993 04 2 Hearth Tax Returns 1664 Houses and their Occupants — The Last Hundred Years 115 The Incumbents 118 The War Memorial 119 AH rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, The Parish Council 120 electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the editor, F. -

Statute Law Revision Bill 2007 ————————

———————— AN BILLE UM ATHCHO´ IRIU´ AN DLI´ REACHTU´ IL 2007 STATUTE LAW REVISION BILL 2007 ———————— Mar a tionscnaı´odh As initiated ———————— ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Definitions. 2. General statute law revision repeal and saver. 3. Specific repeals. 4. Assignment of short titles. 5. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1896. 6. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1962. 7. Miscellaneous amendments to post-1800 short titles. 8. Evidence of certain early statutes, etc. 9. Savings. 10. Short title and collective citation. SCHEDULE 1 Statutes retained PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 [No. 5 of 2007] SCHEDULE 2 Statutes Specifically Repealed PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 ———————— 2 Acts Referred to Bill of Rights 1688 1 Will. & Mary, Sess. 2. c. 2 Documentary Evidence Act 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. 37 Documentary Evidence Act 1882 45 & 46 Vict., c. 9 Dower Act, 1297 25 Edw. 1, Magna Carta, c. 7 Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) (No. 2) 1867 31 & 32 Vict., c. 3 Dublin Hospitals Regulation Act 1856 19 & 20 Vict., c. 110 Evidence Act 1845 8 & 9 Vict., c. 113 Forfeiture Act 1639 15 Chas., 1. c. 3 General Pier and Harbour Act 1861 Amendment Act 1862 25 & 26 Vict., c. -

Caerfallen, Ruthin LL15 1SN

Caerfallen, Ruthin LL15 1SN Researched and written by Zoë Henderson Edited by Gill. Jones & Ann Morgan 2017 HOUSE HISTORY RESEARCH Written in the language chosen by the volunteers and researchers & including information so far discovered PLEASE NOTE ALL THE HOUSES IN THIS PROJECT ARE PRIVATE AND THERE IS NO ADMISSION TO ANY OF THE PROPERTIES ©Discovering Old Welsh Houses Group [North West Wales Dendrochronolgy Project] Contents page no. 1. The Name 2 2. Dendrochronology 2 3. The Site and Building Description 3 4. Background History 6 5. 16th Century 10 5a. The Building of Caerfallen 11 6. 17th Century 13 7. 18th Century 17 8. 19th Century 18 9. 20th Century 23 10. 21st Century 25 Appendices 1. The Royal House of Cunedda 29 2. The De Grey family pedigree 30 3. The Turbridge family pedigree 32 4. Will of John Turbridge 1557 33 5. The Myddleton family pedigree 35 6. The Family of Robert Davies 36 7. Will of Evan Davies 1741 37 8. The West family pedigree 38 9. Will of John Garner 1854 39 1 Caerfallen, Ruthin, Denbighshire Grade: II* OS Grid Reference SJ 12755 59618 CADW no. 818 Date listed: 16 May 1978 1. The Name Cae’rfallen was also a township which appears to have had an Isaf and Uchaf area which ran towards Llanrydd from Caerfallen. Possible meanings of the name 'Caerfallen' 1. Caerfallen has a number of references to connections with local mills. The 1324 Cayvelyn could be a corruption of Caevelyn Field of the mill or Mill field. 2. Cae’rafallen could derive from Cae yr Afallen Field of the apple tree. -

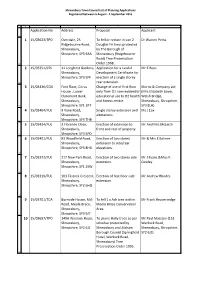

Application No Address Proposal Applicant 1 15/03623/TPO

Shrewsbury Town Council List of Planning Applications Registered between 5 August - 1 September 2015 A B C D E Application No Address Proposal Applicant 1 1 15/03623/TPO Overdale, 25 To fell or reduce in size 2 Dr Warren Perks Ridgebourne Road, Douglas Fir trees protected Shrewsbury, by The Borough of Shropshire, SY3 9AA Shrewsbury (Ridgebourne Road) Tree Preservation 472 Order 1968. 2 15/03351/CPL 11 Longhirst Gardens, Application for a Lawful Mr E Rees Shrewsbury, Development Certificate for Shropshire, SY3 5PF erection of a single storey 473 rear extension. 3 15/03436/COU First Floor, Cirrus Change of use of first floor Morris & Company Ltd House , Lower only from D1 non residential (Mrs Elizabeth Lowe, Claremont Bank, educational use to D2 health Welsh Bridge, Shrewsbury, and fitness centre. Shrewsbury, Shropshire, 474 Shropshire, SY1 1RT SY3 8LH) 4 15/03464/FUL 9 Vane Road, Single storey extension and Ms J Cox Shrewsbury, alterations. 475 Shropshire, SY3 7HB 5 15/03424/FUL 3 Florence Close, Erection of extension to Mr And Mrs McLeish Shrewsbury, front and rear of property. 476 Shropshire, SY3 5PD 6 15/03401/FUL 83 Woodfield Road, Erection of two storey Mr & Mrs E Balmer Shrewsbury, extension to side/rear Shropshire, SY3 8HU elevations. 477 7 15/03372/FUL 217 New Park Road, Erection of two storey side Mr J Evans &Miss K Shrewsbury, extension. Cowley Shropshire, SY1 2SW 478 8 15/03319/FUL 103 Tilstock Crescent, Erection of first floor side Mr Andrew Rhodes Shrewsbury, extension. Shropshire, SY2 6HQ 479 9 15/03701/TCA Burnside House, Mill To fell 1 x Ash tree within Mr Frank Heaversedge Road, Meole Brace, Meole Brace Conservation Shrewsbury, Area. -

10–14 Churchgate: Hallaton's Lost Manor House?

12 10–14 Churchgate: Hallaton’s Lost Manor House? Nick Hill This building, a high quality timber-framed structure dating to the late fifteenth century, has been the subject of a recent programme of detailed recording and analysis, accompanied by dendrochronology. It is located on a prominent site, just opposite the church, at the centre of the village of Hallaton in south-east Leicestershire (OS ref: SP787966). The building, of six bays, had timber-framed walls with heavy close-studding throughout. Three bays originally formed an open hall, with a high arch-braced roof truss of an unusual ‘stub tie beam’ form, a rare Midlands type associated with high status houses. Although this was an open hall, the absence of smoke blackening indicates that there must have been a chimneystack from the beginning rather than an open hearth, an unusually early feature for the late fifteenth century. The whole timber-framed structure is of sophisticated, high class construction, and contrasts strongly with other houses of the period in the village, which are cruck-built. It is suggested that, though subsequently reduced in status and subdivided into four cottages, it was once one of the two main manor houses of Hallaton. The location of this second manor house has been lost since it was merged with the other main manor in the early seventeenth century. Introduction The pair of cottages, now known as 10/12 and 14 Churchgate, stands on a corner site, at the junction of Churchgate with Hunts Lane, immediately to the north-east of Hallaton church. Externally, the building has few features of interest, with cement-rendered walls under a thatched roof (illus. -

Shrewsbury Night Magazine Final Art.Indd 1 10/06/2015 17:21 Be Savvy in Shrewsbury

EAT MEET DANCE SLEEP DISCOVER SHREWSBURY AFTER HOURS Shrewsbury Night Magazine Final art.indd 1 10/06/2015 17:21 BE SAVVY IN SHREWSBURY • If you work locally make sure you take originalshrewsbury.co.uk your Original Shrewsbury loyalty card out and about with you /originalshrewsbury • Download the infoBeetle app for all the @originalshrews latest offers plus direct links to taxi firms to take you home originalshrewsbury • Follow Original Shrewsbury on The magazine was published by Shrewsbury BID. Images courtesy Facebook and Twitter for the latest of Danny Beath, Rachael Chidlow, updates and competitions John Kenyon, Victoria Macken and Richard Wilkinson. • Visit originalshrewsbury.co.uk for news, E: [email protected] T: 01743 358 625 events and local information W: originalshrewsbury.co.uk Shrewsbury BID • Go online and sign up for regular Windsor House, Windsor Place email newsletters Shrewsbury, SY1 2BY Shrewsbury Night Magazine Final art.indd 2 10/06/2015 17:21 WELCOME FEEL LIKE FILLING A NIGHT OUT? THIS IS YOUR GUIDE TO SHREWSBURY AFTER HOURS. FROM HAPPY HOURS TO THE BEST DEALS ON DINNER, WHERE TO GO FOR THE LATEST CINEMA SCREENINGS PLUS PLACES TO RETREAT TO SLEEP. If you like to listen to new music in very old For those trying to savour the last rays of venues, mix mojitos in cool cocktail lounges or sunshine don’t miss a sail along the River feast with friends until late, then you really will Severn or a seat in a secluded beer garden with be spoilt for choice for original night-time fi nds in a fi ne local beverage. -

Shrewsbury in Bloom Portfolio

2019 Portfolio 2019 MAYOR OF SHREWSBURY Contents Councillor Phil Gillam To plant a garden is to believe in tomorrow. So said the great A Warm Welcome 1 film actress and humanitarian Audrey Hepburn. Shrewsbury in Bloom Committee 2 I rather like that quote as it immediately turns all gardeners Review of the Year 4 - 7 and all lovers of flowers into optimists, philosophers and prophets too; and striving for a better tomorrow is surely Illustrating your Achievements something to which we can all relate. Horticultural Achievement 8 - 12 As Mayor of Shrewsbury, it is my very great pleasure to welcome you to our beautiful, historic and enchanting town. Environmental Responsibility 13 - 19 Of course, it is a real privilege to be able to promote our Community Participation 20 - 25 town’s horticultural excellence as we once again enter into the competition season. Conclusion and Future Developments I’d especially like to take this opportunity to thank the Key Achievements in 2018/19 26 volunteers, business sponsors, community groups and other organisations who work together so brilliantly on these Key Aims and Objectives for 2019/20 27 occasions, and I’d like to pay tribute to the Shrewsbury in Appendices 28-29 Bloom Committee for the way in which they encourage everyone to join together to uphold our traditions of horticultural distinction. The Shrewsbury in Bloom Committee takes its environmental responsibilities seriously, and Welcome to beautiful Shrewsbury! we have therefore printed this Bloom portfolio on 100% recycled paper using eco-friendly ink. The Shrewsbury in Bloom Committee asked members of the public to submit their favourite photos of the town as part of their annual photo competition, with the winning entries featured on the front and back covers of the Portfolio. -

Edward II, Vol. 3, P

13 EDWARD II. 395 MEMBRANE 30. Oct. 12. Pardon, at the instance of Geoffrey de Welleford, king's clerk, to the prior York. and convent of Newstead (de Novo Loco) upon Ancolne for acquiring in mortmain, without licence of Edward I or of the present king, from Ralph son of Constance a messuage in Bliburgh, from Patrick Snart a toft in Hibaldestowe, from Reginald de Friseby a toft in the same town, from Adam Strok a toft in the same town, from John Oliver 30 acres of marsh there, from Hugh Odelyn a messuage, 2 acres of land and 1 acre of meadow in Cadenay Husum, and from Robert Snarry 3 acres of land, 1 acre of meadow and a moiety of a messuage in the same town; with licence to retain the said messuages and lands. By p.s. •& € Simple protection for one year for Roger Easy of York. f I Oct. 28. The like for the under-mentioned persons, viz.— j | York. James de Houton, parson of the church of Houton. | Thomas de London, parson of the church of Barton Hanred. I The prior and convent of Boulton in Cravene. I Master John Busshe, sacristan of the chapel of St. Mary and the Holy •| Angels, York. Oct. 14. The prior of Bath, staying in England, has letters nominating Nicholas York. de Weston and Ralph de Sobbury his attorneys in Ireland for two years. Oct. 16. Grant of the king's gift to Geoffrey de Say, in consideration of expenses York. incurred by him in the service of the late king, of the 168£., which by summons of the Exchequer are required for the time of William de Say his father for the scutages on account of the armies for Wales in the fifth and tenth years of the reign of Edward I. -

SHREWSBURY TOWN COUNCIL Planning Committee Meeting Held in the Guildhall, Frankwell Quay, Shrewsbury, SY3 8HR at 6.00Pm on Thurs

SHREWSBURY TOWN COUNCIL Planning Committee Meeting held in the Guildhall, Frankwell Quay, Shrewsbury, SY3 8HR At 6.00pm on Thursday 10 March 2020 PRESENT Councillors N Green (Chairman), J Dean, Ms K Halliday, P Moseley (substituting for P Gillam), K Pardy and Mrs B Wall. IN ATTENDANCE Helen Ball (Town Clerk), Hilary Humphries (Communications Officer) and three members of the pubic. APOLOGIES Apologies were received from Councillors P Gillam, P Nutting and K Roberts. 95/19 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CODE OF CONDUCT (i) Declarations of Pecuniary Interest There were no pecuniary interests declared. (ii) Declarations of Non-Pecuniary Interest Shropshire • Those twin-hatted members declared a personal interest in any matters Councillors relating to the Town Council’s relationship with Shropshire Council. • Declared a personal interest in application 20/00660/VAR as Shropshire Council is the applicant. Councillors J • As a member of Shropshire Council Northern Planning Committee, they Dean and N reserve the right to take a different view of the same applications Green considered in light of any additional information presented to the Northern Planning Committee. All Councillors • Declared a personal interest in application 20/00743/TCA as the Town Council is the applicant. Councillor K • Declared a personal interest in application 20/00770/FUL as he is a Pardy Governor at the school. 96/19 MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING The minutes of the Planning Committee meeting held on 20 February 2020 were submitted as circulated and read. RESOLVED: That the minutes of the Planning Committee meeting held on 20 February 2020 be approved and signed as a correct record.