The Stour Valley Heritage Compendia the Built Heritage Compendium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shropshire Council HER: Monument Full Report 04/10/2019 Number of Records: 99

Shropshire Council HER: Monument Full Report 04/10/2019 Number of records: 99 HER Number Site Name Record Type 01035 Bradling Stone Monument This site represents: a non antiquity of unknown date. Monument Types and Dates NON ANTIQUITY (Unknown date) Evidence NATURAL FEATURE Description and Sources Description A possible chamber tomb <1> At Norton in Hales, are some remains which undoubtedly once formed part of a burial chamber <2a> A large stone standing on the green between the church and an inn associated with a Shrove Tuesday custom of great antiquity <2b> 0220In a plantation, (SJ30343861), formerly stood under a tree on the village green. Stone is natural and not an antiquity <2c> Roughly triangular stone with 1.8m sides and 0.5m thick. It is mounted on three smaller stones on the village green. OS FI 1975 <2> Sources (00) Card index: Site and Monuments Record (SMR) cards (SMR record cards) by Shropshire County Council SMR, SMR Card for PRN SA 01035. Location: SMR Card Drawers (01) Index: Print out by Birmingham University. Location: not given (02) Card index: Ordnance Survey Record Card SJ73NW14 (Ordnance Survey record cards) by Ordnance Survey (1975). Location: SMR OSRC Card Drawers (02a) Volume: Antiquity (Antiquity) by Anon (1927), p29. Location: not given (02b) Monograph: The History and Description of The County of Salop by Hulbert C (1837), p116. Location: not given (02c) Map annotation: Map annotation (County Series) by Anon. Location: Shropshire Archives Location National Grid Reference Centred SJ 7032 3864 (10m by 10m) SJ73NW -

Old Bake House Long

Old Bake House, Church Street, Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk, CO6 4QP Old Bake House StokeOffices at: by Leavenheath Nayland 01206 263007, Suffolk - Long Melford 01787 883144 - Clare 01787 277811 – Castle Hedingham 01787 463404 – Woolpit 01359 245245 – Newmarket 01638 669035 Bury St Edmunds 01284 725525 - London 0207 8390888 - Linton & Villages 01440 784346 Long Mel Old Bake House, Church Street, Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk, CO6 4QP Offices at: Leavenheath 01206 263007 - Long Melford 01787 883144 - Clare 01787 277811 – Castle Hedingham 01787 463404 – Woolpit 01359 245245 – Newmarket 01638 669035 Bury St Edmunds 01284 725525 - London 0207 8390888 - Linton & Villages 01440 784346 Old Bake House, Church Street, Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk, CO6 4QP Stoke by Nayland is one of the areas most favoured villages standing within a designated area of outstanding natural beauty captured in paintings by Gainsborough, Constable and Munnings. There are two award winning restaurants, a primary school and a lovely parish church complemented by a variety of medieval architecture. The A12 is 8 miles and Colchester with its comprehensive range of amenities and commuter rail link to London Liverpool Street Station is 9 miles. This elegant four-bedroom (one en-suite) Grade II listed period village house enjoys a highly accessible central location within the much sought after village of Stoke y Nayland, located on the Suffolk/Essex border. The property has undergone a comprehensive yet sympathetic restoration programme and in its current form the principle residence is complimented by the Old Bake House, a separate detached period cottage. The characterful living accommodation of the principle residence enjoys a seamless blend of both period and contemporary features with exposed timbers and studwork, sash windows and inglenook fire places blending with contemporary oak joinery, underfloor heating, Karndean flooring and bespoke, handmade hardwood shutters. -

Young Colchester: Life Chances, Assets and Anti-Social Behaviour

A LOCAL PARTNERSHIP IMPROVING COMMUNITY SERVICES YOUNG COLCHESTER: LIFE CHANCES, ASSETS AND ANTI-SOCIAL BEHAVIOUR YOUTH SERVICE The Catalyst Project is led by the University of Essex and received £2.2 million funding from the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) and is now monitored by the Office for Students (OfS). The project uses this funding across the following initiatives: Evaluation Empowering public services to evaluate the impact of their work Risk Stratification Using predictive analytics to anticipate those at risk and to better target resources Volunteer Connector Hub Providing benefits to local community and students through volunteering Contact us: E [email protected] T +44 (0) 1206 872057 www.essex.ac.uk/research/showcase/catalyst-project The Catalyst Project The University of Essex Wivenhoe Park Colchester Essex CO4 3SQ 3 Young Colchester: Life Chances, Assets and Anti-Social Behaviour 2018 Contents 0.0 Executive Summary 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Project scope and methods 3.0 Young people in Colchester 4.0 Youth offending, victimisation and safeguarding in Colchester 5.0 Anti-social behaviour in Colchester 6.0 Interventions 7.0 Young people and community assets in Colchester 8.0 Recommendations References Appendices Authors Carlene Cornish, Pamela Cox and Ruth Weir (University of Essex) with Mel Rundle, Sonia Carr and Kaitlin Trenerry (Colchester Borough Council) Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the following A LOCAL PARTNERSHIP IMPROVING organisations for their assistance with this COMMUNITY SERVICES project: Colchester Borough Council Safer Colchester Partnership; Colchester Borough Homes; Colchester Community Policing Team; Colchester Institute; Essex County Council (Organisational Intelligence, Youth Service, Youth Offending Service); Nova (Alternative Provision provider); University of Essex (Catalyst, Make Happen and outreach teams). -

Naylandct February2021 For

Nayland with Wissington Community Times YOUR LOCAL MAGAZINE FOR NEWS AND VIEWS NAYLAND MOURNS ITS RESIDENT GOOSE February 2021 No: 189 SPECIAL INTEREST Coronavirus Information Local Volunteers Community Litterpick Nayland Calendar Village Hall AGM Conservation Soc: ‘John Nash’ THIS ISSUE See It Snap It Remembering Gordon Nayland Bear Christmas Activities Nayland Meadow Improvements Nayland Weather Records Sweet dreams Gordon, photo by Brian Sanders. Tributes to Gordon on pages 21 & 29 River Watch & Stour Notes Nayland History Books THE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF Community Defibrillators NAYLAND WITH WISSINGTON REGULARS COMMUNITY COUNCIL Community Council News Reg Charity No 304926 Parish Council Reports Wednesday 3rd March Village Hall Updates by Zoom at 8pm Society News (CC Executive meeting at 7.30pm) Nayland Surgery News All welcome Church Pages If you wish to attend please contact Rachel Hitchcock [email protected] who will forward you a link to the meeting Garden Notes Further details will be included on the Agenda available from 3rd February Village History at naylandcommunitycouncil.org.uk PLUS Please support YOUR Community Dates for your Diary Anyone interested in joining the Community Council Executive Committee Local Information should contact Rachel Hitchcock 263169 or Julie Clark 263251 Contact Details (on back pages) View the CT in colour on: www.naylandcommunitycouncil.org.uk Page 1 Nayland with Wissington Community Times Nayland with Wissington Parish Council Notes on the summer meeting : 9th December 2020 (Minutes will be available on PC notice board in the High Street or www.naylandandwiston.net after the next meeting) PLANNING for the Clerk to contact Kevin Verlander, the Public Right of Councillors heard that Babergh have given permission to Way Officer at Suffolk CC to seek further support. -

Excursions 2012

SIAH 2013 010 Bu A SIAH 2012 00 Bu A 31 1 1 10 20 12 127 EXCURSIONS 2012 Report and notes on some findings 21 April. Clive Paine and Edward Martin Eye church and castle Eye, Church of St Peter and St Paul (Clive Paine) (by kind permission of Fr Andrew Mitchell). A church dedicated to St Peter was recorded at Eye in 1066. The church was endowed with 240 acres of glebe land, a sure indication that this was a pre-Conquest minster church, with several clergy serving a wide area around Eye. The elliptical shaped churchyard also suggests an Anglo-Saxon origin. Robert Malet, lord of the extensive Honour of Eye, whose father William had built a castle here by 1071, founded a Benedictine priory c. 1087, also dedicated to St Peter, as part of the minster church. It seems that c. 1100–5 the priory was re-established further to the east, at the present misnamed Abbey Farm. It is probable that at the same time the parish church became St Peter and St Paul to distinguish itself from the priory. The oldest surviving piece of the structure is the splendid early thirteenth-century south doorway with round columns, capitals with stiff-leaf foliage, and dog-tooth carving around the arch. The doorway was reused in the later rebuilding of the church, a solitary surviving indication of the high-status embellishment of the early building. The mid fourteenth-century rebuilding was undertaken by the Ufford family of Parham, earls of Suffolk, who were lords of the Honour of Eye 1337–82. -

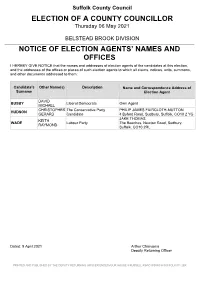

Notice of Election Agents Babergh

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR Thursday 06 May 2021 BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS’ NAMES AND OFFICES I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them: Candidate's Other Name(s) Description Name and Correspondence Address of Surname Election Agent DAVID BUSBY Liberal Democrats Own Agent MICHAEL CHRISTOPHER The Conservative Party PHILIP JAMES FAIRCLOTH-MUTTON HUDSON GERARD Candidate 4 Byford Road, Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 2 YG JAKE THOMAS KEITH WADE Labour Party The Beeches, Newton Road, Sudbury, RAYMOND Suffolk, CO10 2RL Dated: 9 April 2021 Arthur Charvonia Deputy Returning Officer PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY THE DEPUTY RETURNING OFFICER ENDEAVOUR HOUSE 8 RUSSELL ROAD IPSWICH SUFFOLK IP1 2BX Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR Thursday 06 May 2021 COSFORD DIVISION NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS’ NAMES AND OFFICES I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them: Candidate's Other Name(s) Description Name and Correspondence Address of Surname Election Agent GORDON MEHRTENS ROBERT LINDSAY Green Party Bildeston House, High Street, Bildeston, JAMES Suffolk, IP7 7EX JAKE THOMAS CHRISTOPHER -

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

Descendants of Thomas S. Appleby

Descendants of Thomas S. Appleby Thomas S. Appleby Mary Adkin b: Abt 1667 b: Abt 1668 c: 22 Feb 1668-22 Feb 1669 in Boxted, Essex, m: 5 Apr 1688 in St James, Colchester, Essex, England England bu: 26 Mar 1762 in Boxted, Essex, England Thomas S. Appleby Hannah Hart John Appleby Elizabeth Hart Mary Fenn b: Boxted, Essex, England b: Abt 1702 in Boxted ?, Essex, England c: 22 Sep 1691 in Boxted, Essex, England b: Abt 1693 b: Abt 1709 c: 5 Aug 1688 in Boxted, Essex, England m: 22 Oct 1723 in Boxted, Essex, England bu: 21 Feb 1778 in Boxted, Essex, England m: 1713 in Dedham, Essex, England m: 23 Jul 1732 in Boxted, Essex, England d: 15 Nov 1775 in Boxted, Essex, England Thomas Appleby Mary Steady John Appleby Elizabeth Wenlock James Appleby Elizabeth Downes Hannah Appleby John Springet John Appleby Ann Appleby Thomas Grove Mary Appleby Isaac Blyth Sarah Ap c: 18 Oct 1724 in Boxted, Essex, England b: Abt 1740 c: 15 Oct 1727 in Boxted, Essex, England b: Abt 1728 c: 20 Dec 1730 in Boxted, Essex, England b: Abt 1733 c: 8 Sep 1733 in Boxted, Essex, England b: Abt 1733 c: 27 Sep 1736 in Boxted, Essex, England c: 24 Nov 1740 in Boxted, Essex, England b: Abt 1751 b: 21 Mar 1737 in Boxted, Essex, England b: Abt 1741 b: Boxte m: 22 Mar 1761 in Great Horkesley, Essex, bu: 29 May 1804 in Boxted, Essex, England m: 10 Oct 1749 in Boxted, Essex, England m: 8 Jan 1754 in Great Horkesley, Essex, m: 5 Oct 1756 in Boxted, Essex, England d: Jan 1736/1737 m: 24 Oct 1772 in Boxted, Essex, England m: 27 Jan 1763 in Boxted, Essex, England c: 31 Ma England bu: 18 Mar -

Minute Man National Historical Park Concord, Massachusetts

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Historic Architecture Program Northeast Region BATTLE ROAD STRUCTURE SURVEY PHASE II (Phase I included as Appendix) Minute Man National Historical Park Concord, Massachusetts Historic Architecture Program Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation October 2005 Minute Man National Historical Park Battle Road Structure Survey Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………..…………...1 Use Types with Associated Uses for Historic Structures and Associated Landscapes…………………………………………………..………….4 Impact Assessment per Structure and Landscape……………………...…...………...6 Specific Sites: John Nelson House, Barn and Landscape……………………………….……7 Farwell Jones House, James Carty Barn and Landscape…………………...17 McHugh Barn and Landscape…………………………………………………27 Major John Buttrick House and Landscape…………………………...…….32 Noah Brooks Tavern, Rogers Barn and Landscape……………...…………38 Stow- Hardy House, Hovagimian Garage and Landscape…………………46 Joshua Brooks Jr. House and Landscape……………………………………..50 George Hall House and Landscape…………………………………………...54 Gowing- Clarke House and Landscape………………………………………59 Samuel Brooks House and Landscape………………………………………..62 Appendix (Phase I Report)…………………..…………………………………………65 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………...92 i Introduction Purpose of Project The Minute Man National Historical Park Battle Road Structure Survey project was completed in two phases. Phase I, completed in October 2004, determined an impact assessment for the 14 structures and 10 sites included in the project. -

Pick of the Churches

Pick of the Churches The East of England is famous for its superb collection of churches. They are one of the nation's great treasures. Introduction There are hundreds of churches in the region. Every village has one, some villages have two, and sometimes a lonely church in a field is the only indication that a village existed there at all. Many of these churches have foundations going right back to the dawn of Christianity, during the four centuries of Roman occupation from AD43. Each would claim to be the best - and indeed, all have one or many splendid and redeeming features, from ornate gilt encrusted screens to an ancient font. The history of England is accurately reflected in our churches - if only as a tantalising glimpse of the really creative years between the 1100's to the 1400's. From these years, come the four great features which are particularly associated with the region. - Round Towers - unique and distinctive, they evolved in the 11th C. due to the lack and supply of large local building stone. - Hammerbeam Roofs - wide, brave and ornate, and sometimes strewn with angels. Just lay on the floor and look up! - Flint Flushwork - beautiful patterns made by splitting flints to expose a hard, shiny surface, and then setting them in the wall. Often it is used to decorate towers, porches and parapets. - Seven Sacrament Fonts - ancient and splendid, with each panel illustrating in turn Baptism, Confirmation, Mass, Penance, Extreme Unction, Ordination and Matrimony. Bedfordshire Ampthill - tomb of Richard Nicholls (first governor of Long Island USA), including cannonball which killed him. -

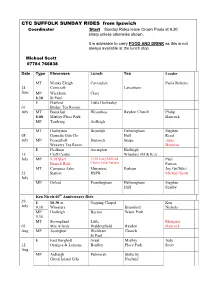

CTC SUFFOLK SUNDAY RIDES from Ipswich Coordinator Start Sunday Rides Leave Crown Pools at 9.30 Sharp Unless Otherwise Shown

CTC SUFFOLK SUNDAY RIDES from Ipswich Coordinator Start Sunday Rides leave Crown Pools at 9.30 sharp unless otherwise shown. It is advisable to carry FOOD AND DRINK as this is not always available at the lunch stop Michael Scott 07784 766838 Date Type Elevenses Lunch Tea Leader MT Monks Eleigh Cavendish Paula Roberts 24 Corncraft Lavenham June MP Wickham Clare 8.30 St Paul E Flatford Little Horkesley 01 Bridge Tea Rooms July MT Breakfast Wivenhoe Raydon Church Philip 8.00 Mistley Place Park Hancock MP Tendring Ardleigh MT Hacheston Brundish Helmingham Stephen 08 Garnetts Gdn Ctr Hall Read July MP Peasenhall Dunwich Snape Anna Weavers Tea Room Brennan E Dedham Assington Hadleigh 15 Craft Centre Wheelers (M & K’s) July MP 9.30 Start 11.30 Long Melford Paul Brunch Ride Cherry Lane Nursery Fenton MT Campsea Ashe Minsmere Parham Joy Griffiths/ 22 Station RSPB Michael Scott July MP Orford Framlingham Helmingham Stephen Hall Searby Ken Nicols 60th Anniversary Ride 29 E 10.30 at Gipping Chapel Ken July 9.30 Wheelers Bramford Nichols MP Hadleigh Bacton Water Park 9.30 MT Stowupland Little Margaret 05 Mrs Allards Waldingfield Raydon Hancock Aug MP Assington Wickham Church St Paul E East Bergholt Great Mistley Judy 12 Oranges & Lemons Bentley Place Park Scott Aug MP Ardleigh Pebmarsh Stoke by Green Island Gdn Nayland Date Type Elevenses Lunch Tea MT Breakfast South Stowmarket Michael 19 7.30 Stoke Ash Lopham Scott Aug MP Breakfast Surlingham Train Home Colin 7.30 Tivetshall Clarke E Debenham Thornham Needham Mkt River Green Alder Carr E Hollesley -

Draft Site Allocations & Development Management Plan

Braintree District Council Draft Site Allocations and Development Management Policies Plan Sustainability Appraisal and Strategic Environmental Assessment Environmental Report – Non Technical Summary January 2013 Environmental Report Non-Technical Summary January 2013 Place Services at Essex County Council Environmental Report Non-Technical Summary January 2013 Contents 1 Introduction and Methodology ........................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Draft Site Allocations and Development Management Plan ........................................ 1 1.3 Sustainability Appraisal and Strategic Environmental Assessment .................................... 1 1.4 Progress to Date ................................................................................................................. 2 1.5 Methodology........................................................................................................................ 3 1.6 The Aim and Structure of this Report .................................................................................. 3 2 Sustainability Context, Baseline and Objectives.............................................................. 4 2.1 Introduction.......................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Plans & Programmes .........................................................................................................