Spring Freeze Damage of Pecan Bloom: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA Spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION for COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE By Ana Maria Metaxas Approved: James Hill Craddock Jennifer Boyd Professor of Biological Sciences Assistant Professor of Biological and Environmental Sciences (Director of Thesis) (Committee Member) Gregory Reighard Jeffery Elwell Professor of Horticulture Dean, College of Arts and Sciences (Committee Member) A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of the Graduate School CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE by Ana Maria Metaxas A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science May 2013 ii ABSTRACT Chestnut cultivars were evaluated for their commercial applicability under the environmental conditions in Hamilton County, TN at 35°13ꞌ 45ꞌꞌ N 85° 00ꞌ 03.97ꞌꞌ W elevation 230 meters. In 2003 and 2004, 534 trees were planted, representing 64 different cultivars, varieties, and species. Twenty trees from each of 20 different cultivars were planted as five-tree plots in a randomized complete block design in four blocks of 100 trees each, amounting to 400 trees. The remaining 44 chestnut cultivars, varieties, and species served as a germplasm collection. These were planted in guard rows surrounding the four blocks in completely randomized, single-tree plots. In the analysis, we investigated our collection predominantly with the aim to: 1) discover the degree of acclimation of grower- recommended cultivars to southeastern Tennessee climatic conditions and 2) ascertain the cultivars’ ability to survive in the area with Cryphonectria parasitica and other chestnut diseases and pests present. -

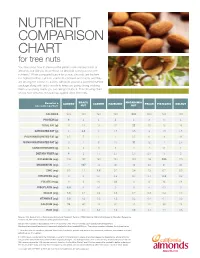

Nutrient Comparison Chart

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

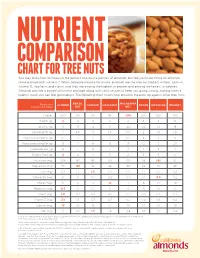

Chart for Tree Nuts

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART FOR TREE NUTS You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the highest in protein and among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a healthy snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT Calories 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 Protein (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 Total Fat (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 18 Saturated Fat (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 Polyunsaturated Fat (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 Monounsaturated Fat (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 Carbohydrates (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 Dietary Fiber (g) 4 2 1 3 2 3 3 2 Potassium (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 Magnesium (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 Zinc (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 Vitamin B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 Folate (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 Riboflavin (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 Niacin (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 Vitamin E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.2 Calcium (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 Iron (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

American Pecan

THE AMERICAN PECAN CRACKING OPEN THE NUTRITION STORY OF OUR NATIVE NUT Scientific evidence suggests but does not prove YOU THINK OF THEM FOR PIE. that eating 1.5 ounces per day of most nuts, YOU ADORE THEM IN PRALINES. such as pecans, as part of a diet low in saturated BUT DID YOU KNOW PECANS fat and cholesterol may reduce the risk of ARE ACTUALLY A NUTRITION heart disease.* POWERHOUSE? U.S. Food and Drug Administration Don’t be fooled by their rich, buttery texture and naturally sweet taste, pecans are extremely *One serving of pecans (28g) contains 18g of unsaturated fat and only 2g of saturated fat. nutrient dense. The macronutrient profile of pecans is appealing to many people: Pecans contain the same beneficial unsaturated protein (3 grams), carbohydrate (4 grams) and fat (20 grams). fats that are found in other nuts, and nearly two decades of research suggests that nuts, including A handful of pecans – about 19 halves – is a good source of fiber, pecans, may help promote heart health. thiamin, and zinc, and an excellent source of copper and manganese – a mineral that’s essential for metabolism and In each 1-ounce serving of raw pecans you’ll get bone health. 12 grams of “good” monounsaturated fat, with zero cholesterol or sodium.1 Compared to other To top it off, pecans contain polyphenols, specifically flavonoids nuts, pecans are among the lowest in carbs and – which are the types of bioactive compounds found in brightly highest in fiber. colored produce.2 So think of pecans as a supernut. -

Castanea Sativa Mill

Forest Ecology and Forest Management Group Tree factsheet images at pages 3, 4, 5, 6 Castanea sativa Mill. taxonomy author, year Miller, … synonym C. vesca Gaertn. Family Fagaceae Eng. Name Sweet Chestnut tree, Spanish Chestnut, European Chestnut Dutch name Tamme kastanje subspecies - varieties - hybrids - cultivars, frequently used references Weeda 2003, Nederlandse oecologische flora, vol.1 (Dutch) PFAF database http://www.pfaf.org/index.html morphology crown habit tree, round max. height (m) 30 max. dbh (cm) 300 actual size Europe 2000? years old, d(..) 197, Etna, Sicily , Italy actual size The Netherlands year 1600-1700, d (130) 270, h 25, Kabouterboom, Beek-Ubbergen year 1810-1820, d(130) 149, h 30 leaf length (cm) 10-27 leaf petiole (cm) 2-3 leaf colour upper surface green leaf colour under surface green leaves arrangement alternate flowering June flowering plant monoecious flower monosexual flower diameter (cm) 1 flower male catkins length (cm) 8-12 pollination wind fruit; length burr (Dutch: bolster) containing 2-3 nuts; 6-8 cm fruit petiole (cm) 1 seed; length nut; 5-6 cm seed-wing length (cm) - weight 1000 seeds (g) 300-1000 seeds ripen September seed dispersal rodents: Apodemus -species – Wood mice - bosmuizen rodents: Sciurus vulgaris - Squirrel - Eekhoorn birds: Garulus glandarius – Jay –Gaai habitat natural distribution Europe, West Asia in N.W. Europe since 9000 B.C. natural areas The Netherlands forests geological landscape types The Netherlands loss-covered terraces, ice pushed ridges (Hoek 1997) forested areas The Netherlands loamy and sandy soils. area Netherlands < 1700 (2002, Probos) % of forest trees in the Netherlands < 0,7 (2002, Probos) soil type pH-KCl indifferent soil fertility nutrient medium to rich light highly shade tolerant as a sapling, shade tolerant when mature shade tolerance 3.2 (0=no tolerance to 5=max. -

Juglans Nigra Juglandaceae L

Juglans nigra L. Juglandaceae LOCAL NAMES English (walnut,American walnut,eastern black walnut,black walnut); French (noyer noir); German (schwarze Walnuß); Portuguese (nogueira- preta); Spanish (nogal negro,nogal Americano) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Black walnut is a deciduous tree that grows to a height of 46 m but ordinarily grows to around 25 m and up to 102 cm dbh. Black walnut develops a long, smooth trunk and a small rounded crown. In the open, the trunk forks low with a few ascending and spreading coarse branches. (Robert H. Mohlenbrock. USDA NRCS. The root system usually consists of a deep taproot and several wide- 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office spreading lateral roots. guide to plant species) Leaves alternate, pinnately compound, 30-70 cm long, up to 23 leaflets, leaflets are up to 13 cm long, serrated, dark green with a yellow fall colour in autumn and emits a pleasant sweet though resinous smell when crushed or bruised. Flowers monoecious, male flowers catkins, small scaley, cone-like buds; female flowers up to 8-flowered spikes. Fruit a drupe-like nut surrounded by a fleshy, indehiscent exocarp. The nut has a rough, furrowed, hard shell that protects the edible seed. Fruits Bark (Robert H. Mohlenbrock. USDA NRCS. 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office produced in clusters of 2-3 and borne on the terminals of the current guide to plant species) season's growth. The seed is sweet, oily and high in protein. The bitter tasting bark on young trees is dark and scaly becoming darker with rounded intersecting ridges on maturity. BIOLOGY Flowers begin to appear mid-April in the south and progressively later until early June in the northern part of the natural range. -

Nutritive Value and Degradability of Leaves from Temperate Woody Resources for Feeding Ruminants in Summer

3rd European Agroforestry Conference Montpellier, 23-25 May 2016 Silvopastoralism (poster) NUTRITIVE VALUE AND DEGRADABILITY OF LEAVES FROM TEMPERATE WOODY RESOURCES FOR FEEDING RUMINANTS IN SUMMER Emile JC 1*, Delagarde R 2, Barre P 3, Novak S 1 Corresponding author: [email protected] mailto:(1) INRA, UE 1373 FERLUS, 86600 Lusignan, France (2) INRA, UMR 1348 INRA-Agrocampus Ouest, 35590 Saint-Gilles, France (3) INRA, UR 4 URP3F, 86600 Lusignan, France 1/ Introduction Integrating agroforestry in livestock farming systems may be a real opportunity in the current climatic, social and economic conditions. Trees can contribute to improve welfare of grazing ruminants. The production of leaves from woody plants may also constitute a forage resource for livestock (Papanastasis et al. 2008) during periods of low grasslands production (summer and autumn). To know the potential of leaves from woody plants to be fed by ruminants, including dairy females, the nutritive value of these new forages has to be evaluated. References on nutritive values that already exist for woody plants come mainly from tropical or Mediterranean climatic conditions (http://www.feedipedia.org/) and very few data are currently available for the temperate regions. In the frame of a long term mixed crop-dairy system experiment integrating agroforestry (Novak et al. 2016), a large evaluation of leaves from woody resources has been initiated. The objective of this evaluation is to characterise leaves of woody forage resources potentially available for ruminants (hedgerows, coppices, shrubs, pollarded trees), either directly by browsing or fed after cutting. This paper presents the evaluation of a first set of 12 woody resources for which the feeding value is evaluated through their protein and fibre concentrations, in vitro digestibility (enzymatic method) and effective ruminal degradability. -

Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Walnut (Juglans Regia L.) Pellicle Tissues Reveals the Regulation of Nut Quality Attributes

life Article Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Pellicle Tissues Reveals the Regulation of Nut Quality Attributes Paulo A. Zaini 1, Noah G. Feinberg 1, Filipa S. Grilo 2 , Houston J. Saxe 1 , Michelle R. Salemi 3, Brett S. Phinney 3 , Carlos H. Crisosto 1 and Abhaya M. Dandekar 1,* 1 Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] (P.A.Z.); [email protected] (N.G.F.); [email protected] (H.J.S.); [email protected] (C.H.C.) 2 Department of Food Sciences and Technology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] 3 Proteomics Core Facility, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] (M.R.S.); [email protected] (B.S.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 November 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 27 November 2020 Abstract: Walnuts (Juglans regia L.) are a valuable dietary source of polyphenols and lipids, with increasing worldwide consumption. California is a major producer, with ‘Chandler’ and ‘Tulare’ among the cultivars more widely grown. ‘Chandler’ produces kernels with extra light color at a higher frequency than other cultivars, gaining preference by growers and consumers. Here we performed a deep comparative proteome analysis of kernel pellicle tissue from these two valued genotypes at three harvest maturities, detecting a total of 4937 J. regia proteins. Late and early maturity stages were compared for each cultivar, revealing many developmental responses common or specific for each cultivar. Top protein biomarkers for each developmental stage were also selected based on larger fold-change differences and lower variance among replicates, including proteins for biosynthesis of lipids and phenols, defense-related proteins and desiccation stress-related proteins. -

Pecan Halves & Pieces

Fort Bend 4-H Pecan Sale 1402 Band Rd . Suite 100 Rosenberg,TX 77471 281-342-3034 PECAN HALVES & PIECES I lb. Bag Pecan Halves—$10.00 I lb. Bag Pecan Pieces—$9.00 3 lb. Box Pecan Halves—$29.00 3 lb. Box Pecan Pieces—$28.00 FLAVORED PECANS & GIFT BASKETS 1 lb. TX Basket Mixed Choc. Pecans 12 oz Praline Frosted Pecans $20.00 $8.00 12 oz Milk Choc. Pecans $7.00 1 lb. Pecan Sampler $14.00 SPECIALTY NUTS 1 lb. Bag Hot & Spicy Peanuts 1 lb. Bag Walnut Halves 12 oz Bag Chocolate Peanuts $4.00 $9.00 $5.00 1 lb. Bag R/S Redskin Peanuts $4.00 MIXES 1 lb. Bag Cran-Slam Mix 1 lb. Bag Fiesta Mix 1 lb. Bag Hunter’s Mix $7.00 $4.00 $6.00 Dried cranberries, walnut pieces, Bbq corn sticks, taco sesame Cashews, cocktail peanuts, roasted and salted almonds, sticks, nacho cheese pea- sesame sticks, sesame roasted and salted sunflower nuts, hot & spicy peanuts seeds, natural almonds, fan- seeds, diced pineapple, black rai- cy pecan halves, peanut oil, sins, roasted and salted pumpkin salt seeds 1 lb. Bag Mountain Mix 1 lb. Texas Deluxe Mix 1 lb. Trash Mix $6.00 $9.00 $4.00 Roasted and salted cocktail Pecan halves, cashews, nat. Cocktail peanuts, hot & spicy pea- peanuts, roasted and salted Almonds, brazil nuts, pea- nuts, pretzels, sesame sticks almonds, roasted and salted nut oil, salt. cashews, raisins, and m&m's WE delicious reach _______________________________________, Would ________________________________________. Turn 15. 14. 13. 12. 11. -

The Conversion of Abandoned Chestnut Forests to Managed Ones Does Not Affect the Soil Chemical Properties and Improves the Soil Microbial Biomass Activity

Article The Conversion of Abandoned Chestnut Forests to Managed Ones Does Not Affect the Soil Chemical Properties and Improves the Soil Microbial Biomass Activity Mauro De Feudis 1,* , Gloria Falsone 1, Gilmo Vianello 2 and Livia Vittori Antisari 1 1 Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences, Alma Mater Studiorum—University of Bologna, Via Fanin, 40, 40127 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] (G.F.); [email protected] (L.V.A.) 2 Centro Sperimentale per lo Studio e l’Analisi del Suolo (CSSAS), Alma Mater Studiorum—University of Bologna, 40127 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 June 2020; Accepted: 19 July 2020; Published: 22 July 2020 Abstract: Recently, several hectares of abandoned chestnut forests (ACF) were recovered into chestnut stands for nut or timber production; however, the effects of such practice on soil mineral horizon properties are unknown. This work aimed to (1) identify the better chestnut forest management to maintain or to improve the soil properties during the ACF recovery, and (2) give an insight into the effect of unmanaged to managed forest conversion on soil properties, taking in consideration sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) forest ecosystems. The investigation was conducted in an experimental chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) forest located in the northern part of the Apennine chain (Italy). We identified an ACF, a chestnut forest for wood production (WCF), and chestnut forests 1 for nut production with a tree density of 98 and 120 plants ha− (NCFL and NCFH, respectively). WCF, NCFL and NCFH stands are the result of the ACF recovery carried out in 2004. -

Naturalization of Almond Trees (Prunus Dulcis) in Semi-Arid Regions

*Manuscript Click here to view linked References 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Naturalization of almond trees (Prunus dulcis) in semi-arid 10 11 regions of the Western Mediterranean. 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 1 2 1,3 19 Pablo Homet-Gutierrez , Eugene W. Schupp , José M. Gómez * 20 1Departamento de Ecología, Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad de Granada, España. 21 2 22 Department of Wildland Resources and the Ecology Center. Utah State University. USA. 23 3Dpt de Ecología Evolutiva y Funcional, Estación Experimental de Zonas Aridas (EEZA-CSIC), 24 25 Almería, España. 26 27 28 *Corresponding author 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 1 63 64 65 Abstract 1 Agricultural land abandonment is rampant in present day Europe. A major consequence of this 2 3 phenomenon is the re-colonization of these areas by the original vegetation. However, some 4 agricultural, exotic species are able to naturalize and colonize these abandoned lands. In this 5 6 study we explore the ability of almonds (Prunus dulcis D.A. Webb.) to establish in abandoned 7 croplands in semi-arid areas of SE Iberian Peninsula. Domesticated during the early Holocene 8 9 in SW Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean, the almond has spread as a crop all over the world. 10 We established three plots adjacent to almond orchards on land that was abandoned and 11 12 reforested with Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) and Holm oak (Quercus ilex L.) about 20 13 years ago. -

Easyclean® Matt Emulsion [email protected]

MyRoomPainter Download our free Myroompainter app Win to visualise your colour scheme. crownpaints.co.uk Visit our website for our full range of £100 colours and more inspiration. worth of high street vouchers We to see how your Look Book love For more colour inspiration painting projects turn out – share see our latest Look Book available from our website. your photos on Instagram by tagging us in @crownpaintsuk and tell us what colours you’ve used with the hashtag #crownpaints and #colourwithcrown Matchpots & And you could win £100 Pure Paint® worth of high street vouchers Colour Samples to complete your scheme. If you want to see how these colours look in your home, try our Matchpots® available in store or A5 Pure Paint® Colour The Palette Samples from crownpaints.co.uk Alternatively email us your images at Aftershow® Easyclean® Matt Emulsion [email protected] T&C’s apply, see website for details. Follow us on new colours Our colours Lines open Monday - Friday 8.30 am - 5.30 pm Please recycle after use. ] (except Bank Holidays) 0330 0240281 Calls charged at the national rate. at a glance Advice from Crown. new ® Crown, the Crown Logo, Breatheasy®, Matchpots®, If you are using more than one pack of paint of the same colour, in the same area, mix Superscrubbable™, Mouldguard+™, Antibacterial+™, together in a large container to ensure you get consistency of colour. Some colours easyclean Crown Pure Paint® Colours, Crown Colour Match® may require additional coats to give complete coverage. We make every effort to All the emulsion colours for walls & ceilings from all and all the colours marked TM or ® are trade marks of ensure perfect colour reproduction, but owing to print limitations the colours may matt emulsion Crown Brands Ltd.