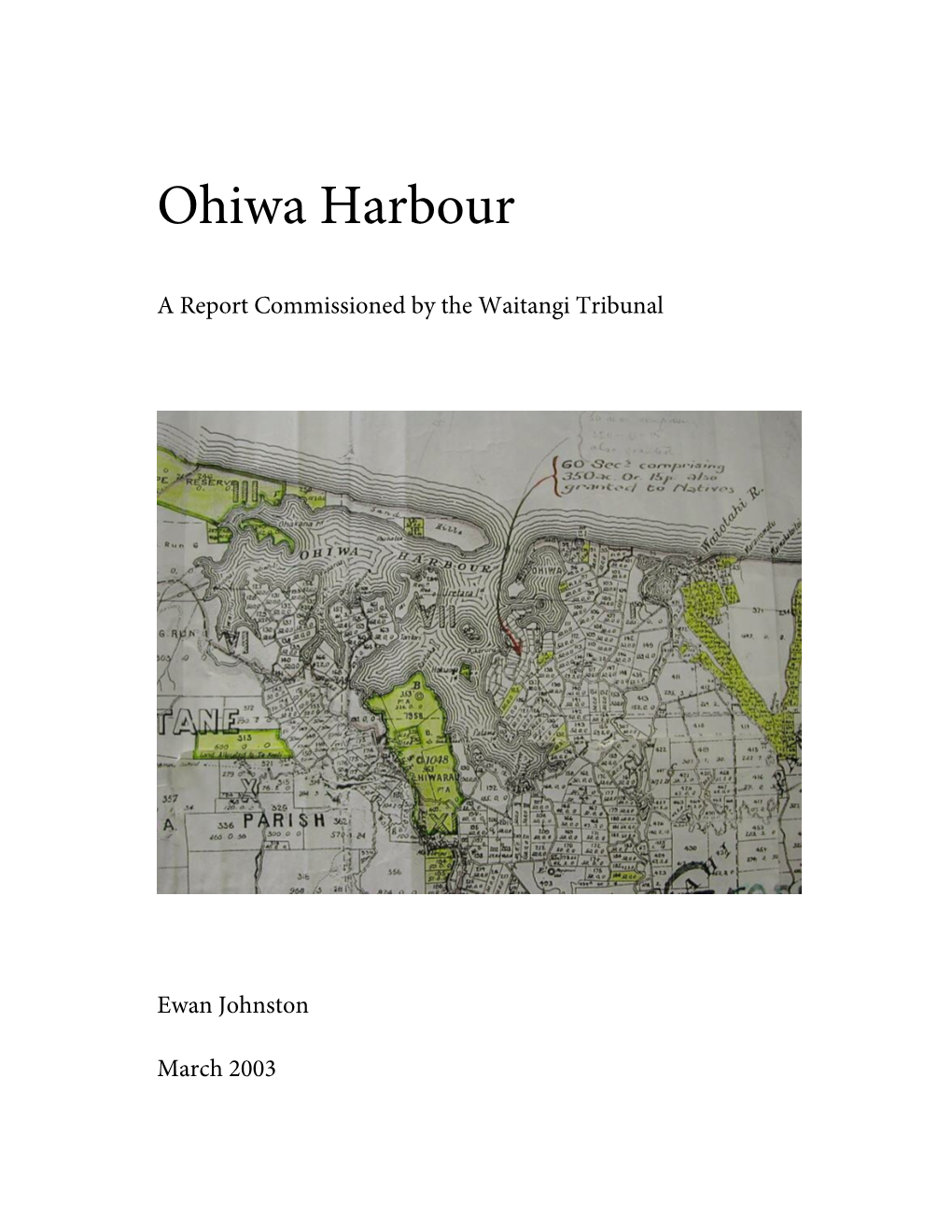

Ohiwa Harbour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Arboreal Heritage for Twenty-First-Century Aotearoa New Zealand

NATURAL MONUMENTS: RETHINKING ARBOREAL HERITAGE FOR TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND Susette Goldsmith A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2018 ABSTRACT The twenty-first century is imposing significant challenges on nature in general with the arrival of climate change, and on arboreal heritage in particular through pressures for building expansion. This thesis examines the notion of tree heritage in Aotearoa New Zealand at this current point in time and questions what it is, how it comes about, and what values, meanings and understandings and human and non-human forces are at its heart. While the acknowledgement of arboreal heritage can be regarded as the duty of all New Zealanders, its maintenance and protection are most often perceived to be the responsibility of local authorities and heritage practitioners. This study questions the validity of the evaluation methods currently employed in the tree heritage listing process, tree listing itself, and the efficacy of tree protection provisions. The thesis presents a multiple case study of discrete sites of arboreal heritage that are all associated with a single native tree species—karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus). The focus of the case studies is not on the trees themselves, however, but on the ways in which the tree sites fill the heritage roles required of them entailing an examination of the complicated networks of trees, people, events, organisations, policies and politics situated within the case studies, and within arboreal heritage itself. Accordingly, the thesis adopts a critical theoretical perspective, informed by various interpretations of Actor Network Theory and Assemblage Theory, and takes a ‘counter-’approach to the authorised heritage discourse introducing a new notion of an ‘unauthorised arboreal heritage discourse’. -

Kaihu Valley and the Ripiro West Coast to South Hokianga

~ 1 ~ KAIHU THE DISTRICT NORTH RIPIRO WEST COAST SOUTH HOKIANGA HISTORY AND LEGEND REFERENCE JOURNAL FOUR EARLY CHARACTERS PART ONE 1700-1900 THOSE WHO STAYED AND THOSE WHO PASSED THROUGH Much has been written by past historians about the past and current commercial aspects of the Kaipara, Kaihu Valley and the Hokianga districts based mostly about the mighty Kauri tree for its timber and gum but it would appear there has not been a lot recorded about the “Characters” who made up these districts. I hope to, through the following pages make a small contribution to the remembrance of some of those main characters and so if by chance I miss out on anybody that should have been noted then I do apologise to the reader. I AM FROM ALL THOSE WHO HAVE COME BEFORE AND THOSE STILL TO COME THEY ARE ME AND I AM THEM ~ 2 ~ CHAPTERS CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY CHARACTERS NAME YEAR PLACE PAGE Toa 1700 Waipoua 5 Eruera Patuone 1769 Northland 14 Te Waenga 1800 South Hokianga 17 Pokaia 1805 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 30 Murupaenga 1806 South Hokianga – Ripiro Coast 32 Kawiti Te Ruki 1807 Ahikiwi – Ripiro Coast 35 Hongi Hika 1807 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 40 Taoho 1807 Kaipara – Kaihu Valley 44 Te Kaha-Te Kairua 1808 Ripiro Coast 48 Joseph Clarke 1820 Ripiro Coast 49 Samuel Marsden 1820 Ripiro Coast 53 John Kent 1820 South Hokianga 56 Jack John Marmon 1820 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 58 Parore Te Awha 1821 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 64 John Martin 1827 South Hokianga 75 Moetara 1830 South Hokianga - Waipoua 115 Joel Polack -

The Ngati Awa Raupatu Report

THE NGATI AWA RAUPATU REPORT THE NGAT I AWA RAUPATU REPORT WA I 46 WAITANGI TRIBUNAL REPORT 1999 The cover design by Cliä Whiting invokes the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the consequent interwoven development of Maori and Pakeha history in New Zealand as it continuously unfolds in a pattern not yet completely known A Waitangi Tribunal report isbn 1-86956-252-6 © Waitangi Tribunal 1999 Edited and produced by the Waitangi Tribunal Published by Legislation Direct, Wellington, New Zealand Printed by PrintLink, Wellington, New Zealand Text set in Adobe Minion Multiple Master Captions set in Adobe Cronos Multiple Master LIST OF CONTENTS Letter of transmittal. ix Chapter 1Chapter 1: ScopeScopeScope. 1 1.1 Introduction. 1 1.2 The raupatu claims . 2 1.3 Tribal overlaps . 3 1.4 Summary of main åndings . 4 1.5 Claims not covered in this report . 10 1.6 Hearings. 10 Chapter 2: Introduction to the Tribes. 13 2.1 Ngati Awa and Tuwharetoa . 13 2.2 Origins of Ngati Awa . 14 2.3 Ngati Awa today . 16 2.4 Origins of Tuwharetoa. 19 2.5 Tuwharetoa today . .20 2.6 Ngati Makino . 22 Chapter 3: Background . 23 3.1 Musket wars. 23 3.2 Traders . 24 3.3 Missionaries . 24 3.4 The signing of the Treaty of Waitangi . 25 3.5 Law . 26 3.6 Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. 28 Chapter 4: The Central North Island Wars . 33 4.1 The relevance of the wars to Ngati Awa. 33 4.2 Conclusion . 39 Chapter 5: The Völkner And Fulloon Slayings . -

Notice of an Ordinary Council Meeting

NOTICE OF AN ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING Ōpōtiki District Council Chambers, 108 St John Street, Ōpōtiki Thursday, 5 September 2019 Commencing at 9.00am ORDER PAPER OPENING KARAKIA / PRAYER / INSPIRATIONAL READING – Councillor McRoberts APOLOGIES DECLARATION OF ANY INTERESTS IN RELATION TO OPEN MEETING AGENDA ITEMS PUBLIC FORUM Extinction Rebellion representatives – Climate Change Declaration Page ITEM 01 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES – ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING 23 JULY 2019 4 ITEM 02 MINUTES – COAST COMMUNITY BOARD MEETING 18 JUNE 2019 18 ITEM 03 MINUTES – CIVIL DEFENCE EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT GROUP JOINT 23 COMMITTEE MEETING 21 JUNE 2019 ITEM 04 MAYORAL REPORT – 19 JULY 2019 – 30 AUGUST 2019 31 ITEM 05 ŌPŌTIKI MARINE ADVISORY GROUP (OMAG) UPDATE 36 ITEM 06 DELEGATIONS TO THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER DURING INTERIM ELECTION 39 PERIOD ITEM 07 TE TAHUHU O TE RANGI – LIBRARY REDEVELOPMENT 45 and separate document ITEM 08 OPTIONS FOR MAKING A DECLARATION ON CLIMATE CHANGE 65 ITEM 09 ŌPŌTIKI DISTRICT COUNCIL RESERVE MANAGEMENT PLAN POLICIES AND 84 PROCEDURES and separate document ITEM 10 REPEAL OF THE ŌPŌTIKI DISTRICT COUNCIL EARTHQUAKE-PRONE BUILDINGS 90 POLICY 2006 ITEM 11 PROGRESS REPORT ON THE IDENTIFICATION OF ‘PRIORITY’ EARTHQUAKE- 93 PRONE BUILDINGS AND CONSULTATION ON THOROUGHFARES (Continued over page) ITEM 12 2019 REVIEW OF THE ŌPŌTIKI DISTRICT COUNCIL DANGEROUS AND 107 INSANITARY BUILDINGS POLICY ITEM 13 WAINUI ROAD SAFETY IMPROVEMENTS FUNDING 119 ITEM 14 LAND TRANSPORT FUNDING 2019-20 122 ITEM 15 SUMMER FESTIVAL FUNDING APPLICATIONS 125 ITEM -

Full Publication

COVER IMAGE Leafa Wilson/Olga Krause Ich Heisse Olga Krause, Deutsche Kuenstlerin 2005 Poster print (detail). Image reproduced in full below. The life-long work of performance artist Leafa Wilson/Olga Krause began in 2005. These propagandist poster-styled works are loosely based around the Russian Constructivist design aesthetic adopted by the German band ‘Kraftwerk’. With both Samoan and German ancestry, the artist reconciles their past and present by creating utopic race relations in the site of their body: I am Olga Krause, German artist (Ich Heisse Olga Krause, Deutsche Kuenstlerin) GUEST EDITOR Amelia Williams EDITOR Nadia Gush EDITORIAL ADVISORY GROUP Giselle Byrnes, Massey University Te Kunenga Ki Purehuroa, Palmerston North. Catharine Coleborne, University of Newcastle, Australia. Nadia Gush, Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato, Hamilton; University of Waikato Te Whare Wānanga o Waikato, Hamilton. Stephen Hamilton, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Australia; Massey University Te Kunenga Ki Purehuroa, Palmerston North. Bronwyn Labrum, Canterbury Museum, Christchurch. Mark Smith, Oamaru Whitestone Civic Trust, Oamaru. NZJPH7.1 2020 ISSN 2253-153X © 2020 The New Zealand Journal of Public History 7.1 HISTORY AND RECONCILIATION Amelia Williams EDITORIAL 1 Leah Bell DIFFICULT HISTORIES 7 Vincent O’Malley STREET TALK: HISTORY, MYTH AND MEMORY ON THE WAIKATO FRONTIER 13 Graeme Ball THE LONG HISTORY OF LEARNING ABOUT OUR OWN HISTORY 20 Renika Sicilliano ‘IWI’ HISTORIES IN TE TIRITI O WAITANGI SETTLEMENTS: THE IMPACT OF A CROWN FRAMEWORK ON OUR NARRATIVE HISTORIES 31 Geoff Canham KOPURERERUA AUETU: THE VALE OF TEARS 39 Nicholas Haig SUMMARY: Once More, With Feeling 47 Charlotte Greenhalgh REVIEW: Past Caring? Women, Work and Emotion 51 HISTORY AND RECONCILIATION, MĀ MURI Ā MUA KA TIKA. -

And Taewa Māori (Solanum Tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Traditional Knowledge Systems and Crops: Case Studies on the Introduction of Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and Taewa Māori (Solanum tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of AgriScience in Horticultural Science at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand Rodrigo Estrada de la Cerda 2015 Kūmara and Taewa Māori, Ōhakea, New Zealand i Abstract Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and taewa Māori, or Māori potato (Solanum tuberosum), are arguably the most important Māori traditional crops. Over many centuries, Māori have developed a very intimate relationship to kūmara, and later with taewa, in order to ensure the survival of their people. There are extensive examples of traditional knowledge aligned to kūmara and taewa that strengthen the relationship to the people and acknowledge that relationship as central to the human and crop dispersal from different locations, eventually to Aotearoa / New Zealand. This project looked at the diverse knowledge systems that exist relative to the relationship of Māori to these two food crops; kūmara and taewa. A mixed methodology was applied and information gained from diverse sources including scientific publications, literature in Spanish and English, and Andean, Pacific and Māori traditional knowledge. The evidence on the introduction of kūmara to Aotearoa/New Zealand by Māori is indisputable. Mātauranga Māori confirms the association of kūmara as important cargo for the tribes involved, even detailing the purpose for some of the voyages. -

New Zealand G.Azette

Jumb. 5. 233 THE NEW ZEALAND G.AZETTE WELLINGTON, THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 1937. Land taken for the Purposes of a Road in Block XV, Land taken for the Purposes of paddocking Driven Cattle in I:leretaunga Survey District, Iiawke's Bay County. Block XV, Iieretaunga Survey District, 'Jlawke's Bay County. [L.S.] GALWAY, Governor-General. A PROCLAMATION. [L.S.] GALvVAY, Governor-General. N pursuance and exercise of the powers and authorities A PROCLAMATION. I vested in me by the Public Works Act, 1928, and of every other power and authority in anywise enabling me in N pursuance and exercise of the powers and authorities this behalf, I, George Vere Arundell, Viscount Galway, I vested in me by the Public Works Act, 1928, and of Governor-General of the Dominion of New Zealand, do hereby every other power and authority in anywise enabling me in proclaim and declare that the land described in tho Schedule this behalf, I, George Vere Arundell, Viscount Galway, hereto is hereby taken for the purposes of a road; and I Governor-General of the Dominion of New Zealand, do hereby do also declare that this Proclamation shall take effect on proclaim and declare that the land described in the Schedule and after the first day of February, one thousand nine hereto is hereby taken for the purposes of paddocking driven hundred and thirty-seven. cattle, and shall vest in the Chairman, Councillors, and Inhabitants of the County of Hawke's Bay as from the date hereinafter mentioned; and I do also declare that this Procla SCHEDULE. -

Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand

A supplementary finding-aid to the archives relating to Maori Schools held in the Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand MAORI SCHOOL RECORDS, 1879-1969 Archives New Zealand Auckland holds records relating to approximately 449 Maori Schools, which were transferred by the Department of Education. These schools cover the whole of New Zealand. In 1969 the Maori Schools were integrated into the State System. Since then some of the former Maori schools have transferred their records to Archives New Zealand Auckland. Building and Site Files (series 1001) For most schools we hold a Building and Site file. These usually give information on: • the acquisition of land, specifications for the school or teacher’s residence, sometimes a plan. • letters and petitions to the Education Department requesting a school, providing lists of families’ names and ages of children in the local community who would attend a school. (Sometimes the school was never built, or it was some years before the Department agreed to the establishment of a school in the area). The files may also contain other information such as: • initial Inspector’s reports on the pupils and the teacher, and standard of buildings and grounds; • correspondence from the teachers, Education Department and members of the school committee or community; • pre-1920 lists of students’ names may be included. There are no Building and Site files for Church/private Maori schools as those organisations usually erected, paid for and maintained the buildings themselves. Admission Registers (series 1004) provide details such as: - Name of pupil - Date enrolled - Date of birth - Name of parent or guardian - Address - Previous school attended - Years/classes attended - Last date of attendance - Next school or destination Attendance Returns (series 1001 and 1006) provide: - Name of pupil - Age in years and months - Sometimes number of days attended at time of Return Log Books (series 1003) Written by the Head Teacher/Sole Teacher this daily diary includes important events and various activities held at the school. -

Indigenous Bodies: Ordinary Lives

CHAPTER 8 Indigenous Bodies: Ordinary Lives Brendan Hokowhitu Ōpōtiki Red with cold Māori boy feet speckled with blades of colonial green Glued with dew West water wept down from Raukūmara mountains Wafed up east from the Pacifc Anxiety, ambiguity, madness1 mbivalence is the overwhelming feeling that haunts my relationship with physicality. Not only my body, but the bodies of an imagined multitude of AIndigenous peoples dissected and made whole again via the violent synthesis of the colonial project. Like my own ambivalence (and by “ambivalence” I refer to simultaneous abhorrence and desire), the relationship between Indigenous peoples and physicality faces the anxiety of representation felt within Indigenous studies in general. Tis introduction to the possibilities of a critical pedagogy is one of biopolitical transformation, from the innocence of jumping for joy, to the moment I become aware of my body, the moment of self-consciousness in the archive, in knowing Indigenous bodies written upon and etched by colonization, and out the other side towards radical Indigenous scholarship. Tis is, however, not a narrative of modernity, of transformation, of transcendence of the mind through the body. I didn’t know it then, but this transformation was a genealogical method un- folding through the production of corporeality: part whakapapa (genealogy), part comprehension of the biopolitics that placate and make rebellious the Indigenous 164 Indigenous Bodies: Ordinary Lives body. Plato’s cave, Descartes’ blueprint, racism, imperial discourse, colonization, liberation, the naturalness of “physicality” and “indigeneity.” Tis madness only makes sense via the centrality of Indigenous physicality. Physicality is that terminal hub, the dense transfer point where competing, contrasting, synthesizing, and dissident concepts hover to make possible the various ways that the Indigenous body materializes through and because of colonization. -

Developing a National Framework for Monitoring the Grey-Faced Petrel (Pterodroma Gouldi) As an Indicator Species

Developing a national framework for monitoring the grey-faced petrel (Pterodroma gouldi) as an indicator species J.C. Russell, J.R. Welch, S. Dromzée, K. Bourgeois, J. Thoresen, R. Earl, B. Greene, I. Westbrooke and K. McNutt DOC RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT SERIES 350 Contributors: JR, KM, BG and JW wrote the manuscript JR, KM, BG and IW designed the study JW and IW analysed the data JW, KB, SD and JT undertook fieldwork RE drew the maps DOC Research & Development Series is a published record of scientific research carried out, or advice given, by Department of Conservation staff or external contractors funded by DOC. It comprises reports and short communications that are peer-reviewed. This report is available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Series. © Copyright December 2017, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1177–9306 (web PDF) ISBN 978–1–98–478–851445–1 (web PDF) This report was prepared for publication by the Publishing Team; editing by Amanda Todd and Lynette Clelland; layout by Lynette Clelland. Publication was approved by the Director, Planning and Support Unit, Biodiversity Group, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. Published by Publishing Team, Department of Conservation, PO Box 10420, The Terrace, Wellington 6143, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. CONTENTS Abstract 1 1. Introduction 2 1.1 Grey-faced petrel as an indicator species 2 1.1.1 Natural history 2 1.1.2 Population regulation 3 1.1.3 Measures of population size 4 1.1.4 Survey methods 4 1.2 Objectives 5 2. -

First Years at Hokianga 1827 – 1836

First Years at Hokianga 1827-1836 by Rev.C.H.Laws FIRST YEARS AT HOKIANGA 1827 – 1836 In a previous brochure, entitled "Toil and Adversity at Whangaroa," the story of the Methodist Mission to New Zealand is told from its initiation in 1823 to its disruption and the enforced flight of the missionaries in 1827. After a brief stay with members of the Anglican Mission at the Bay of Islands the Methodist party sailed for Sydney in the whaler "Sisters" on January 28th, 1827, arriving at their destination on February 9th. It consisted of Nathaniel Turner and Mrs. Turner, with their three children, John Hobbs, James Stack and Mr. and Mrs. Luke Wade, and they took with them a Maori girl and two native lads. William White had left Whangaroa for England on September 19th, 1825, and at the time of the flight had not returned. The catastrophe to the Mission was complete. The buildings had been burned to the ground, the live stock killed; books and records destroyed, and the property of the Mission now consisted only of a few articles in store in Sydney which had not been forwarded to New Zealand. Wesley Historical Society (NZ) Publication #4(2) 1943 Page 1 First Years at Hokianga 1827-1836 by Rev.C.H.Laws Chapter I The departure of the Mission party for Sydney is seen, as we look back upon it, to have been the right course. Sydney was their headquarters, they were a large party and could not expect to stay indefinitely with their Anglican friends, and it could not be foreseen when they would be able to re-establish the work. -

Te Pai Tawhiti: Exploring the Horizons of Māori Economic Performance Through Effective Collaboration

Te Pai Tawhiti: Exploring the Horizons of Māori Economic Performance through Effective Collaboration Final Report 2016 Te Pai Tawhiti: Exploring the Horizons of Māori Economic Performance through Effective Collaboration Prepared by Dr Robert Joseph ArapetaFinal Tahana Report Jonathan Kilgour2016 Dr Jason Mika Te Mata Hautū Taketake GHA Pare Consulting GHA University of Waikato MylenePrepared Rakena by Te Puritanga Jefferies UniversityDr Robert of JosephWaikato GHAArapeta Tahana Jonathan Kilgour Dr Jason Mika Te Mata Hautū Taketake GHA Pare Consulting GHA PreparedUniversity for of Waikato Ngā Pae o Te Māramatanga Mylene Rakena Te Puritanga Jefferies 2016 University of Waikato GHA Prepared for Ngā Pae o Te Māramatanga Research Partners 2016 Research Partners Ngāti Pikiao iwi and hapū Ngāti Pikiao iwi and hapū Above Illustration The above illustration is a view of Lake Rotoehu, looking at the Ngāti Pikiao maunga Matawhaura. Most Ngāti Pikiao people view Matawhaura from Lake Rotoiti. Viewing Matawhaura from a different perspective to what Ngāti Pikiao are used to offers a valuable analogy of viewing what Ngāti Pikiao have from a different perspective which aligns with the theses of this report. CONTENTS DIAGRAMS, TABLES, MAPS & GRAPHS .................................................................................. 7 HE MIHI ................................................................................................................................. 8 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................