Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perfil Del Proyecto

Perfil Técnico Económico Pavimentación del tramo: Aldea Panabaj Santiago Atitlán – Aldea Chicajay San Pedro La Laguna Dirección General de Caminos CONTENIDO GENERAL NUMERO CONTENIDO PÁGINA 1. CONSIDERACIONES GENERALES…………………. 01 1.1 Antecedentes del proyecto…………………………….. 01 2. INDENTIFICACIÓN DEL PROYECTO……………….. 01 3. ANALISIS DE LA PROBLEMATICA…………………... 01 3.1 Situación sin proyecto…………………………………… 01 3.2 Situación con proyecto………………………………….. 04 4. MARCO JURIDICO POLÍTICO DEL PROYECTO……. 04 5. LOCALIZACIÓN DEL PROYECTO……………………. 05 5.1 Macrolocalización………………………………………… 05 5.2 Microlocalización…………………………………………. 05 6. AREA DE INFLUENCIA…………………………..……… 05 7. OBJETIVOS GENERALES Y ESPECIFICOS………… 07 7.1 Objetivo general………………………………………….. 07 7.2 Objetivos específicos…………………………………….. 07 8. META………………………………………………………. 08 9. JUSTIFICACIÓN………………………………………….. 08 10. POBLACIÓN BENEFICIADA……………………………. 08 10.1 Población actual………………………………………….. 08 10.2 Población futura………………………………………….. 09 10.3 Servicios para uso de la población……………………… 09 11. ESTUDIO DE MERCADO………………………………. 10 11.1 Transito promedio diario anual TPDA………..………… 10 11.2 Proyección del tránsito promedio diario anual…..……. 11 12. CRONOGRAMA DE ACTIVIDADES…………………… 12 13. COSTO DEL PROYECTO………………………………. 13 13.1 Costo de ejecución………………………………………. 13 13.2 Costo de mantenimiento………………………………… 14 14. ESPECIFICACIONES TÉCNICAS…………………….. 14 15. DERECHO DE VÍA………………………………………. 15 16. FUENTE FINANCIERA DEL PROYECTO……………. 15 17. CONCLUSIONES Y RECOMENDACIONES…………. 18 17.1 Conclusiones……………………………………………… -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Divination & Decision-Making: Ritual Techniques of Distributed Cognition in the Guatemalan Highlands Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2v42d4sh Author McGraw, John Joseph Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Divination and Decision-Making: Ritual Techniques of Distributed Cognition in the Guatemalan Highlands A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology and Cognitive Science by John J. McGraw Committee in charge: Professor Steven Parish, Chair Professor David Jordan, Co-Chair Professor Paul Goldstein Professor Edwin Hutchins Professor Craig McKenzie 2016 Copyright John J. McGraw, 2016 All rights reserved. The dissertation of John J. McGraw is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ Co-chair ___________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page …....……………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents ………………….……………………………….…………….. iv List of Figures ….…………………………………………………….…….……. -

Santiago Atitlán

AMSCLAE AUTORIDAD PARA EL MANEJO SUSTENTABLE DE LA CUENCA DEL LAGO DE AT ITLÁN Y SU ENTORNO – AMSCLAE - INGA. LUISA CIFUENTES AGUILAR D I R E C TO R A EJECUTIVA SITUACIÓN ACTUAL DEL LAGO DE ATITLÁN 2019 TRANSPARENCIA 2016-2018 Fechas de muestreo 2016 2017 2018 W14 WA WB WC WD WE WG WP W14 WA WB WC WD WE WG WP SA WA WB WC WD CWG WP 0 2 4 6 Profundidad(m) 8 10 Valores promedio de transparencia por sitio de marzo a noviembre del 2018 (DICA/AMSCLAE, 2018). En los 60´s Presente NIVEL DEL LAGO DE ATITLÁN 2016-2019 1557.5 Nivel Promedio Nivel Máximo 1557.0 1556.5 1556.0 1555.5 Oscilación Oscilación Nivel (msnm) 1555.0 1554.5 Ene Feb Mar Abr May Jun Jul Ago Sep Oct Nov Dic Ene Feb Mar Abr May Jun Jul Ago Sep Oct Nov Dic Ene Feb Mar Abr May Jun Jul Ago Sep Oct Nov Dic 2016 2017 2018 Fechas de Muestreo Logros en Manejo de Residuos líquidos – Aguas Residuales, etc. ➢Diagnóstico de poblados urbanos ➢Estrategia para el manejo integral de aguas residuales aprobada ➢Avances en solución Integral: Avances en Ortofotos, diseño de drenajes y redes de agua potable, estudio técnico de una propuesta de solución (AALA) Avances en propuestas de financiamiento (BCIE y BID). ➢Estudio Técnico de Aguas Residuales en seis (6) municipios de la cuenca (San Andrés Semetabaj, Panajachel, Santa Catarina Palopó, Santiago Atitlán, San Juan la Laguna y San Antonio Palopó) ➢Construcción o ampliación de sistemas de tratamiento de aguas residuales (SNIP) ➢2016 - San José Chacayá ➢2017 - San Marcos la Laguna y San Andrés Semetabaj ➢2018 – (8) Concepción, Panajachel, San Juan -

Juan Skinner Alvarado, Msc Member of the Scientific Committee AGENDA

Integrated Lake Basin Management (ILBM): obstacles and opportunities for wastewater management in the lake Atitlán basin Juan Skinner Alvarado, MSc Member of the Scientific Committee AGENDA: 1. Integrated Lake Basin Management - ILBM 2. Background of wastewater management infrastructure development in the lake Atitlán basin – lessons learned 3. Obstacles in wastewater management at the lake Atitlán Basin 4. Opportunities in wastewater management for lake Atitlán. 1. Integrated Lake Basin Management ILBM Manejo Integrado de Cuencas de Lagos LBMILBMI– Lake Basin Management Initiative Una revisión global sobre el manejo de cuencas de lagos Analiza e identifica las lecciones aprendidas de la experiencia de manejo de 28 lagos del mundo. Análisis de las amenazas A definition of Integrated Lake Basin Management (ILBM) is coined with the LBMI Integrated Lake Basin Management (ILBM) is an approach to achieve the sustainable management of lakes and reservoirs through gradual, continuous and comprehensive improvements in the governance of the basin, including efforts to integrate institutional responsibilities, public policies, participation of interest groups, scientific and traditional knowledge, technological options, and financing prospects and their restrictions. La gobernanza es una noción que busca -antes que imponer un modelo- describir una transformación sistémica compleja, que se produce a distintos niveles -de lo local a lo mundial- y en distintos sectores -público, privado y civil-.(Fuente: wikipedia) The 6 lake basin governance pillars Un marco teórico para el análisis y planificación de la gestión de lagos ILEC Scicom More Sustainable 3. Seek ways to strengthen the governance pillars 2. Identify issues, needs and challenges Monitoring, Reconnaissance Survey, Inventory and Databases LevelofSustainability 1. -

Departamento De Sololá Municipio De San Juan La Laguna

CODIGO: AMENAZA POR DESLIZAMIENTOS E INUNDACIONES 717 DEPARTAMENTO DE SOLOLÁ 8 MUNICIPIO DE SAN JUAN LA LAGUNA AMEN AZA POR DESLIZAMIEN TOS 410000.000000 415000.000000 91°21'W " 91°18'W Tzumajui La p re d ic c ión d e e sta am e naza utiliza la m e tod ología re c onoc id a te " a l " Sierra Cerro u d e Mora-V ahrson, p ara e stim ar las am e nazas d e d e slizam ie ntos a h Parraxquim Chuichich a " N un nive l d e d e talle d e 1 kilóm e tro. Esta c om p le ja m od e lac ión utiliza ío R una c om b inac ión d e d atos sob re la litología, la hum e d ad d e l sue lo, p e nd ie nte y p ronóstic os d e tie m p o e n e ste c aso p re c ip itac ión ac um ulad a que CATHALAC ge ne ra d iariam e nte a través d e l m od e lo m e sosc ale PSU/N CAR, e l MM5. "Camanoj Río Ugualeox Se e stim a e sta am e naza e n térm inos d e ‘Baja’, ‘Me d ia’ y ‘Alta‘. x o e Tzumajul l " Río Uga ualeox u g Finca Las U Delicias o " í R Alta á z t A a y Z a rián A P o Xip N o í E Rí R M A E D L Media E V I Santa Clara la Laguna San Pablo La Laguna N "Pak ‹Wex " Cerro Chicut ^ (Santa Baja Clara) "Xiprian AMEN AZA R "Chuipoj ío Na Chacap hu " la POR IN UN DACION ES te La p re d ic c ión d e e sta am e naza utiliza la m e tod ología d e Te rraV ie w SAN TA MARIA "Pala V ISITACION ^4.2.2 y su p lugin Te rraHyd ro (S.Rossini). -

Wastewater Management in the Basin of Lake Atitlan: a Background Study

WASTEWATER MANAGEMENT IN THE BASIN OF LAKE ATITLAN: A BACKGROUND STUDY LAURA FERRÁNS, SERENA CAUCCI, JORGE CIFUENTES, TAMARA AVELLÁN, CHRISTINA DORNACK, HIROSHAN HETTIARACHCHI WORKING PAPER - No. 6 WORKING PAPER - NO. 6 WASTEWATER MANAGEMENT IN THE BASIN OF LAKE ATITLAN: A BACKGROUND STUDY LAURA FERRÁNS, SERENA CAUCCI, JORGE CIFUENTES, TAMARA AVELLÁN, CHRISTINA DORNACK, HIROSHAN HETTIARACHCHI Table of Contents 1. Introduction 5 2. Regional Settings of the Study Area 7 2.1 General Aspects of Guatemala 7 2.2 Location and Population of the Lake Atitlan Basin 8 2.3 Economy of the Region 9 2.4 Hydraulic Characteristics of Lake Atitlan 9 2.5 Water Quality of Lake Atitlan 9 2.5.1 Pollution by Organic and Inorganic Substances 10 2.5.2 Pollution by Pathogens 11 2.6 Impacts on the Region due to Inappropriate Wastewater Management 12 2.6.1 Impacts on Human Health 12 2.6.2 Environmental Impacts on the Lake 13 2.6.3 Economic Impacts 13 3. Wastewater Management in Lake Atitlan 13 3.1 Status of Sanitation Services in the Lake Atitlan Basin 14 3.2 Amount of Wastewater Produced in the Lake Atitlan Basin 15 3.3 Available WWTPs at the Lake Atitlan Basin 16 3.4 Performance of WWTPs Located in the Lake Atitlan Basin 18 3.5 Operation and Maintenance of WWTPs Located in the Lake Atitlan Basin 20 3.5.1 Bottlenecks 20 3.5.2 Potential Solutions 22 4. Major Findings: A Summary 24 Acknowledgment 25 References 26 Wastewater Management in the Basin of Lake Atitlan: A Background Study Laura Ferráns1, Serena Caucci1, Jorge Cifuentes2, Tamara Avellán1, Christina Dornack3, Hiroshan Hettiarachchi1 1 UNU-FLORES, Dresden, Germany 2 Department of Engineering and Nanotechnology of Materials, University of San Carlos of Guatemala, Guatemala City, Guatemala 3 Institute of Waste Management and Circular Economy, TU Dresden, Dresden, Germany ABSTRACT This working paper presents a study on the current wastewater management situation in the basin of Lake Atitlan, Guatemala. -

El Municipio De Nahualá, Actualmente Cuenta Con

SISTEMAS INFRAESTRUCTURALES Red de Carreteras y Caminos Rurales Carreteras: El municipio de Nahualá, actualmente cuenta con una cinta asfáltica, que es la carretera interamericana, desde la ciudad capital de Guatemala, pasa por la ciudad de Sololá, directamente hacia este municipio, esta cinta asfáltica en todas las épocas del año se mantiene en buenas condiciones, por lo que los visitantes locales, nacionales como extranjeras no tienen por que preocuparse a la llegada en el municipio. Además de la carretera interamericana, el municipio de Nahualá, cuenta con dos estradas principales hacia la cabecera municipal, la primera en el lado ESTE del municipio y la segunda en el OESTE camino que dirige hacia la ciudad de Quetzaltenango, Totonicapán y cuatro caminos. Dichas entradas, están asfaltadas, se encuentran en buenas condiciones durante todas las épocas del año, el tiempo máximo a recorrer de los dos entradas hacia la cabecera municipal son de 5 minutos. Servicios Básicos El nivel de cobertura y calidad de servicios básicos con que cuenta el Municipio son: educación, salud, energía eléctrica, agua potable, alumbrado público, drenajes, letrinas, extracción de basura., mercado, cementerio, rastro, seguridad y otros, sirven de parámetro para la medición del nivel de vida de la población en general. Agua El servicio de agua que se presta en el área urbana y rural del Municipio no se le practica ningún proceso de purificación por lo que no puede considerarse como agua potable, es agua entubada que es extraída de los nacimientos naturales que generan las zonas montañosas del mismo. Letrinas En la mayoría de comunidades rurales utilizan las letrinas como medio de saneamiento de excrementos humanos, porque no cuenta con sistema de drenajes. -

References: Acknowledgements

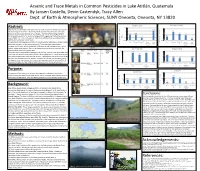

Arsenic and Trace Metals in Common Pesticides in Lake Atitlán, Guatemala By Jansen Costello, Devin Castendyk, Tracy Allen Dept. of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences, SUNY Oneonta, Oneonta, NY 13820 Arsenic (As) Manganese (Mn) Abstract: 100 - 10 Lake Atitlán in Guatemala is the main drinking water source for several communities 13.38 3.2 10 µg/L situated along the shoreline. Studies by SUNY Oneonta show that lake water has - 1.5 0.79 0.56 dissolved arsenic concentrations of 11-13 µg/L. The World Health Organization’s 1 1 0.8 drinking water guideline for arsenic is 10 µg/L (REF), suggesting that lake water may 0.5 0.07 per Liter pose a health risk. This study seeks to determine whether local pesticide use may µg/L 0.1 0.21 contribute to observed arsenic levels. 0.01 0.1 The watershed surrounding Lake Atitlán is heavily used for agriculture. Farmers apply Rival Tambo 44 Totem 72 Super Lake Rival Tambo 44 Totem 72 Super Lake Microgram Microgram pesticides to crops in order to increase yields. These pesticides many contain per Liter MIcrogram EC SL Herbaxon Atitlan EC SL Herbaxon Atitlán Figure #7 inorganic constituents which are harmful to humans at high concentrations, such as 20 SL 20 SL Table #1 arsenic, copper, and mercury. Rain rinses these constituents from corps and into Chromium (Cr) Image Pesticide Manufacturer Solution pH Electric Copper (Cu) 9.5 streams, which then flow into the lake. Name Conductivity 10 7.4 10 This experiment measured the composition of the four most common pesticides used (µS/cm) 6.9 Rival Duwest, 50g per 16 L 4.13 1198 µg/L µg/L 4.9 - - 2 in the watershed which we purchased from a farm supply store in Sololá in 2014, plus Honduras 0.7 0.702 two unknown pesticides collected from farmers. -

Situación De Agua Y Saneamiento En La Cuenca Del Lago De Atitlán

SITUACIÓN DE AGUA Y SANEAMIENTO EN LA CUENCA DEL LAGO DE ATITLÁN AUTORIDAD PARA EL MANEJO SUSTENTABLE DE LA CUENCA DEL LAGO DE AT ITLÁN Y SU ENTORNO – AMSCLAE - INGA. LUISA CIFUENTES AGUILAR DIRECTORA EJECUTIVA NOVIEMBRE 2018 Morfología de la Cuenca del Lago Atitlán Área: 546 km2 Área espejo de agua: 125.7 km2 Perímetro: 101.6 km Volumen de agua que almacena: 25.4 km3 Profundidad máxima: 327.5 m Profundidad media: 202.4 m Tiempo de retención hidráulica: 80 años Romero 2009. Densidad poblacional: 800 hab/km2 (media nacional 150 hab/km2). Erosión promedio: 18-24 ton/ha/año Desechos sólidos: Arpox. 40,800 TM/año Lago en transición de Oligotrófico a Mesotrófico Romero 2009. PROBLEMÁTICA CALIDAD DE AGUA DEL LAGO DE ATITLÁN TRANSPARENCIA A TRAVÉS DE LOS AÑOS En los 60´s Presente PROBLEMÁTICA CALIDAD DEL AGUA EN CUERPOS DE AGUA SUPERFICIAL Se tienen monitoreados 15 cuerpos de agua superficial, de los cuales únicamente 3 presentan un índice ICA arriba de 71 (considerados con calidad Buena), el resto se encuentran por debajo (de Regular a Mala). SITUACIÓN DEL SUMINISTRO DE AGUA EN LOS PROBLEMÁTICA POBLADOS DE LA CUENCA DEL LAGO DE ATITLÁN No. De sistemas de No. DE SISTEMAS CON POBLACION abastecimiento de agua para RANGO DE CONTAMINACION No. MUNICIPIO TOTAL CLORACION TOTAL TOTAL 2018 INE el consumo URBANA RURAL URBANA RURAL URBANA RURAL 1 SOLOLÁ 156,807 6 165 171 5 1 6 0 2 a INCONTABLES 2 CONCEPCIÓN 8,041 4 6 10 3 1 4 1 a 16 2 a INCONTABLES 3 PANAJACHEL 21,011 3 1 4 3 0 3 1 a 44 1 a 3 4 SAN ANDRÉS SEMETABAJ 14,955 2 19 21 2 9 11 1 a 12 -

The Towns Op Lake Atitlan by Sol Tax

THE TOWNS OP LAKE ATITLAN BY SOL TAX MICROFILM COLLECTION OP MANUSCRIPTS ON MIDDLE AMERICAN CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY No. 13 UNIVERSITY OP CHICAGO LIBRARY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 1946 // INTRODUCTION In October of 1936, the author and his wife settled In Panajaohel, on the north shore of Atitlan, to pursue investigations of the Indians of Guatemala undertaken by the Carnegie Institution of Washington. The field season, which lasted eight months, was to be devoted to the study of several of the towns of the lake. With the aid of a fast launch, we began periodic visits to several of the towns, especially Santa Catarina Palop6 and San Marcos la laguna. Before the season was over, we were joined by Dr. Manuel J. Andrade, who was undertaking a linguistic survey of th^&ame communities, and for part of the time, we travelled together. His notes on the lake towns are published in this microfilm collection (No. 11). Also during the season we were joined by Dr. Lila M. O'Neale, who undertook a study of the textiles of Highland Guatemala. The results of her studies are published as, "Textiles of Highland Guatemala", Ca-'negir Institution of Washington. Publication 567. 1945. In succeeding years, the authors made a thorough study of the town of Panajachel itself, the results of which are to be printed; SeRor Juan Rosales made a thorough study of the town of San Pedro la laguna, the results of which are also publishedjby the Guatemalan government; and Dr. Robert Redfield spent considerable time in the town of San Antonio Palopo and the ladino community of Agua Escondida of the same municipio. -

Municipio De San Juan La Laguna Departamento De Sololá

MUNICIPIO DE SAN JUAN LA LAGUNA DEPARTAMENTO DE SOLOLÁ “COSTOS Y RENTABILIDAD DE UNIDADES ARTESANALES (TEJIDOS TÍPICOS)”. MARIO RENÉ URBINA CASTRO TEMA GENERAL “DIAGNÓSTICO SOCIOECONÓMICO, POTENCIALIDADES PRODUCTIVAS Y PROPUESTAS DE INVERSIÓN”. MUNICIPIO DE SAN JUAN LA LAGUNA DEPARTAMENTO DE SOLOLÁ TEMA INDIVIDUAL “COSTOS Y RENTABILIDAD DE UNIDADES ARTESANALES (TEJIDOS TIPICOS)”. FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA 2,008 2,008 (c) FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS EJERCICIO PROFESIONAL SUPERVISADO UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA SAN JUAN LA LAGUNA – VOLUMEN 13 2-60-75-CPA-2008 Impreso en Guatemala, C.A. UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS “COSTOS Y RENTABILIDAD DE UNIDADES ARTESANALES (TEJIDOS TÍPICOS)” MUNICIPIO DE SAN JUAN LA LAGUNA DEPARTAMENTO DE SOLOLÁ INFORME INDIVIDUAL Presentado a la Honorable Junta Directiva y al Comité Director del Ejercicio Profesional Supervisado de la Facultad de Ciencias Económicas por MARIO RENÉ URBINA CASTRO previo a conferírsele el título de CONTADOR PÚBLICO Y AUDITOR en el Grado Académico de LICENCIADO Guatemala, mayo de 2,008 ACTO QUE DEDICO A DIOS Por darme la vida, ser fortaleza, esperanza y fuente de sabiduría y permitirme alcanzar este triunfo. A LA VIRGEN DEL ROSARIO Por escuchar mis oraciones. A MI PAÌS Que sea como un granito de arena para su engrandecimiento y desarrollo. A MIS PADRES José Raúl (+) y Blanca Armenia Por su amor, confianza y ser la fuente de valores y principios que conducen mi vida. A MI ESPOSA Myrna Elizabeth Por el apoyo brindado durante la carrera y comprender que el sacrificio es la base del éxito. -

0705 PPM Nahualá Sololá

1 2 ÍNDICE Contenido INTRODUCCIÓN .................................................................................................................................. 5 CAPITULO I .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Marco Legal e Institucional ...................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Marco Institucional ................................................................................................................... 9 CAPITULO II ....................................................................................................................................... 10 2 Marco de Referencia ................................................................................................................. 10 2.1 Ubicación Geográfica .......................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Educación ............................................................................................................................ 11 2.3 Proyección Poblacional ...................................................................................................... 15 2.4 Sistema de Salud ................................................................................................................. 16 2.5 Seguridad y Justicia ...........................................................................................................