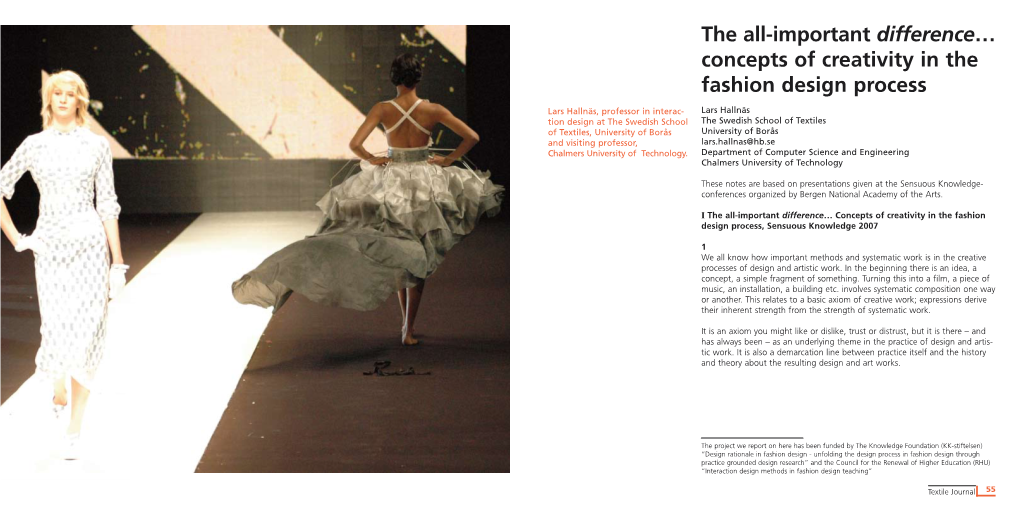

The All-Important Difference… Concepts of Creativity in the Fashion Design Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shaping New Knowledges

PAPER ABSTRACT BOOK SHAPINGSHAPING NEWNEW KNOWLEDGESKNOWLEDGES ROBERT CORSER SHARON HAAR 2016 ACSA 104TH ANNUAL MEETING Shaping New Knowledges CO-CHAIRS Robert Corser, University of Washington Sharon Haar, University of Michigan HOST SCHOOLS University of Washington Copyright © 2016 Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, Inc., except where otherwise restricted. All rights reserved. No material may be reproduced without permission of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture 1735 New York Ave., NW Washington, DC 20006 www.acsa-arch.org 2 – 2016 ACSA 104th Annual Meeting Abstract Book CONTENTS THURSDAY, MARCH 17 FRIDAY, MARCH 18 SATURDAY, MARCH 19 2:00PM - 3:30PM 11:00AM - 12:30PM 9:00AM - 10:30AM 05 Acting Out: The Politics and Practices of 15 Divergent Modes of Engagement: 31 Beginnings in the Context of New Interventions: Session 1 Exploring the Spectrum of Collaborative Knowledge Mireille Roddier, U. Michigan and Participatory Practices: Session 1 Catherine Wetzel, IIT Caryn Brause, U. Massachusetts, Amherst James Sullivan, Louisiana State U. 06 Architecture is Philosophy: Beyond the Joseph Krupczynski, U. Massachusetts, Post-Critical: Session 1 Amherst 32 Open: Hoarding, Updating, Drafting: Mark Thorsby, Lone Star College The Production of Knowledge in Thomas Forget, U. N. Carolina @ Charlotte 16 Knowledge Fields: Between Architecture Architectural History and Landscape: Session 1 Sarah Stevens, U. of British Columbia Cathryn Dwyre, Pratt Institute 07 Open: Challenging Materiality: Industry Chris Perry, RPI Collaborations Reshaping Design 33 Water, Water Everywhere…: Session 1 Julie Larsen, Syracuse U. Jori A. Erdman, Louisiana State U. Roger Hubeli, Syracuse U. 17 Knowledge in the Public Interest Nadia M. -

What Knowledge Is of Most Worth in Engineering Design Education?

Integrated Design: What Knowledge is of Most Worth in Engineering Design Education? Richard Devon Sven Bilén 213 Hammond 213 Hammond Pennsylvania State University Pennsylvania State University PA 16802 PA 16802 [email protected] sbilé[email protected] Alison McKay Alan de Pennington Dep’t. of Mechanical Engineering Dep’t. of Mechanical Engineering University of Leeds University of Leeds Leeds LS2 9JT, UK Leeds LS2 9JT, UK [email protected] [email protected] Patrick Serrafero Javier Sánchez Sierra Ecole Centrale de Lyon Esc. Sup. de Ingenieros de Tecnun 17 Chemin du Petit Bois Universidad de Navarra F-69130 Lyon-Ecully, France 20018 San Sebastián, Spain [email protected] [email protected] Abstract This paper is based on the premise that the design ideas and methods that cut across most fields of engineering, herein called integrated design, have grown rapidly in the last two or three decades and that integrated design now has the status of cumulative knowledge. This is old news for many, but a rather limited approach to teaching design knowledge is still common in the United States and perhaps elsewhere. In many engineering departments in the United States, students are only required to have a motivational and experiential introductory design course that is followed several years later by an experiential and discipline-specific capstone course [1]. Some limitations of the capstone approach, such as too little and too late, have been noted [2]. In some departments, and for some students, another experiential design course may be taken as an elective. A few non-design courses have an experiential design project added following a design across the curriculum approach. -

Budgen, Software Design Methods

David Budgen The Loyal Opposition Software Design Methods: Life Belt or Leg Iron? o software design methods have a correctly means “study of method.”) To address, but future? In introducing the January- not necessarily answer, this question, I’ll first consider D February 1998 issue of IEEE Software,Al what designing involves in a wider context, then com- Davis spoke of the hazards implicit in pare this with what we do, and finally consider what “method abuse,”manifested by a desire this might imply for the future. to “play safe.”(If things go well, you can take the credit, but if they go wrong, the organization’s choice of method can take the blame.) As Davis argues, such a THE DESIGN PROCESS policy will almost certainly lead to our becoming builders of what he terms “cookie-cutter, low-risk, low- Developing solutions to problems is a distinguish- payoff, mediocre systems.” ing human activity that occurs in many spheres of life. The issue I’ll explore in this column is slightly dif- So, although the properties of software-based systems ferent, although it’s also concerned with the problems offer some specific problems to the designer (such as that the use of design methods can present. It can be software’s invisibility and its mix of static and dynamic expressed as a question: Will the adoption of a design properties), as individual design characteristics, these method help the software development process (the properties are by no means unique. Indeed, while “life belt” role), or is there significant risk that its use largely ignored by software engineers, the study of the will lead to suboptimum solutions (the “leg iron”role)? nature of design activities has long been established Robert L. -

Generative Design Rationale: Beyond the Record and Replay Paradigm

Knowledge Systems Laboratory December 1991 Technical Report KSL 92-59 Updated February 1993 Generative Design Rationale: Beyond the Record and Replay Paradigm by Thomas R. Gruber Daniel M. Russell To appear in a forthcoming collection on design rationale edited by Thomas Moran and John Carroll, to be published by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. KNOWLEDGE SYSTEMS LABORATORY Computer Science Department Stanford University Stanford, California 94305 Generative Design Rationale: Beyond the Record and Replay Paradigm Thomas R. Gruber Daniel M. Russell Knowledge Systems Laboratory Systems Sciences Laboratory Stanford University Xerox Palo Alto Research Center 701 Welch Road, Building C 3333 Coyote Hill Road Palo Alto, CA 94304 Palo Alto, CA 94304 [email protected] [email protected] Updated February 1993 Abstract. Research in design rationale support must confront the fundamental questions of what kinds of design rationale information should be captured, and how rationales can be used to support engineering practice. This paper examines the kinds of information used in design rationale explanations, relating them to the kinds of computational services that can be provided. Implications for the design of software tools for design rationale support are given. The analysis predicts that the “record and replay” paradigm of structured note-taking tools (electronic notebooks, deliberation notes, decision histories) may be inadequate to the task. Instead, we argue for a generative approach in which design rationale explanations are constructed, in response to information requests, from background knowledge and information captured during design. Support services based on the generative paradigm, such as design dependency management and rationale by demonstration, will require more formal integration between the rationale knowledge capture tools and existing engineering software. -

Privacy When Form Doesn't Follow Function

Privacy When Form Doesn’t Follow Function Roger Allan Ford University of New Hampshire [email protected] Privacy When Form Doesn’t Follow Function—discussion draft—3.6.19 Privacy When Form Doesn’t Follow Function Scholars and policy makers have long recognized the key role that design plays in protecting privacy, but efforts to explain why design is important and how it affects privacy have been muddled and inconsistent. Tis article argues that this confusion arises because “design” has many different meanings, with different privacy implications, in a way that hasn’t been fully appreciated by scholars. Design exists along at least three dimensions: process versus result, plan versus creation, and form versus function. While the literature on privacy and design has recognized and grappled (sometimes implicitly) with the frst two dimensions, the third has been unappreciated. Yet this is where the most critical privacy problems arise. Design can refer both to how something looks and is experienced by a user—its form—or how it works and what it does under the surface—its function. In the physical world, though, these two conceptions of design are connected, since an object’s form is inherently limited by its function. Tat’s why a padlock is hard and chunky and made of metal: without that form, it could not accomplish its function of keeping things secure. So people have come, over the centuries, to associate form and function and to infer function from form. Software, however, decouples these two conceptions of design, since a computer can show one thing to a user while doing something else entirely. -

Introduction: Design Epistemology

Design Research Society DRS Digital Library DRS Biennial Conference Series DRS2016 - Future Focused Thinking Jun 17th, 12:00 AM Introduction: Design Epistemology Derek Jones The Open University Philip Plowright Lawrence Technological University Leonard Bachman University of Houston Tiiu Poldma Université de Montréal Follow this and additional works at: https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/drs-conference-papers Citation Jones, D., Plowright, P., Bachman, L., and Poldma, T. (2016) Introduction: Design Epistemology, in Lloyd, P. and Bohemia, E. (eds.), Future Focussed Thinking - DRS International Conference 20227, 27 - 30 June, Brighton, United Kingdom. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2016.619 This Miscellaneous is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at DRS Digital Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in DRS Biennial Conference Series by an authorized administrator of DRS Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction: Design Epistemology Derek Jonesa*, Philip Plowrightb, Leonard Bachmanc and Tiiu Poldmad a The Open University b Lawrence Technological University c University of Houston d Université de Montréal * [email protected] DOI: 10.21606/drs.2016.619 “But the world of design has been badly served by its intellectual leaders, who have failed to develop their subject in its own terms.” (Cross, 1982) This quote from Nigel Cross is an important starting point for this theme: great progress has been made since Archer’s call to provide an intellectual foundation for design as a discipline in itself (Archer, 1979), but there are fundamental theoretical and epistemic issues that have remained largely unchallenged since they were first proposed (Cross, 1999, 2007). -

Design for an Unknown Future: Amplified Roles for Collaboration, New Design Knowledge, and Creativity Stephanie Wilson, Lisa Zamberlan

Design for an Unknown Future: Amplified Roles for Collaboration, New Design Knowledge, and Creativity Stephanie Wilson, Lisa Zamberlan Introduction The field of design has expanded significantly in recent years. In Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/desi/article-pdf/31/2/3/1715404/desi_a_00318.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 addition to engaging in the design of artifacts, designers are apply- ing their skills in a wide range of areas that include organizational design, service design, strategic design, interaction design, and design for social innovation. The rapid development of these areas is, in part, propelled by a broad recognition of design thinking and practice as a significant driver of innovation. This recognition is reflected in the establishment of government-funded design labs, such as MindLab in Denmark and Helsinki Design Lab in Finland. The potential of design to transform the public sector has also recently been recognized in Australia through the development of the Centre for Excellence in Public Service Design. Although recent research has identified new and emerging roles for design and the designer in the twenty-first century, a num- ber of areas remain underexplored in the literature. This article examines several of these areas, including the designer’s role as co- creator in collaborative and interdisciplinary teams, as well as the designer’s role in generating new design knowledge and in devel- oping and contributing to cultures of creativity. Examples from practice are used to illuminate the growing importance of these roles in design and for designers as they navigate the complexity of today’s design challenges. -

Fashion Design

FASHION DESIGN FAS 112 Fashion Basics (3-0) 3 crs. FAS Fashion Studies Presents fashion merchandise through evaluation of fashion products. Develops awareness of construction, as well as FAS 100 Industrial Sewing Methods (1-4) 3 crs. workmanship and design elements, such as fabric, color, Introduces students to basic principles of apparel construction silhouette and taste. techniques. Course projects require the use of industrial sewing equipment. Presents instruction in basic sewing techniques and FAS 113 Advanced Industrial Sewing Methods (1-4) 3 crs. their application to garment construction. (NOTE: Final project Focuses on application and mastery of basic sewing skills in should be completed to participate in the annual department Little pattern and fabric recognition and problem solving related to Black Dress competition.) individual creative design. Emphasis on technology, technical accuracy and appropriate use of selected materials and supplies. FAS 101 Flat Pattern I (1-4) 3 crs. (NOTE: This course is intended for students with basic sewing Introduces the principles of patternmaking through drafting basic skill and machine proficiency.) block and pattern manipulation. Working from the flat pattern, Prerequisite: FAS 100 with a grade of C or better or placement students will apply these techniques to the creation of a garment as demonstrated through Fashion Design Department testing. design. Accuracy and professional standards stressed. Pattern Contact program coordinator for additional information. tested in muslin for fit. Final garment will go through the annual jury to participate in the annual department fashion show. FAS 116 Fashion Industries Career Practicum and Seminar Prerequisite: Prior or concurrent enrollment in FAS 100 with a (1-10) 3 crs. -

Theoretically Comparing Design Thinking to Design Methods for Large- Scale Infrastructure Systems

The Fifth International Conference on Design Creativity (ICDC2018) Bath, UK, January 31st – February 2nd 2018 THEORETICALLY COMPARING DESIGN THINKING TO DESIGN METHODS FOR LARGE- SCALE INFRASTRUCTURE SYSTEMS M.A. Guerra1 and T. Shealy1 1Civil Engineering, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, USA Abstract: Design of new and re-design of existing infrastructure systems will require creative ways of thinking in order to meet increasingly high demand for services. Both the theory and practice of design thinking helps to exploit opposing ideas for creativity, and also provides an approach to balance stakeholder needs, technical feasibility, and resource constraints. This study compares the intent and function of five current design strategies for infrastructure with the theory and practice of design thinking. The evidence suggests the function and purpose of the later phases of design thinking, prototyping and testing, are missing from current design strategies for infrastructure. This is a critical oversight in design because designers gain much needed information about the performance of the system amid user behaviour. Those who design infrastructure need to explore new ways to incorporate feedback mechanisms gained from prototyping and testing. The use of physical prototypes for infrastructure may not be feasible due to scale and complexity. Future research should explore the use of prototyping and testing, in particular, how virtual prototypes could substitute the experience of real world installments and how this influences design cognition among designers and stakeholders. Keywords: Design thinking, design of infrastructure systems 1. Introduction Infrastructure systems account for the vast majority of energy use and associated carbon emissions in the United States (US EPA, 2014). -

A Prototype Framework for Knowledge-Based Analog Circuit Synthesis* Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Background

A Prototype Framework for Knowledge-Based Analog Circuit Synthesis* Ramesh Harjani, Rob A. Rutenbar and L. Richard Carley Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Carnl:gie Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 Abstract Analog design is commonly perceived to be one of the most knowledge-intensive of design tasks: the techniques needed to An organization for a knowledge-based analog (circuit build good analog circuits seem to exist solely as expertise in- synthesis tool is described. Analog circuit topologies are vested in individual designers. represented as a hierarchy of functional blocks; a planning This paper describes a knowledge-based framework for an mechanism is introduced to translate performance specifica- analog circuit synthesis tool. Although “knowledge-based” tions between levels in this circuit hierarchy. A prototype im- has come to be synonymous with “rule-based” in CAD ap- plementation, OASYS, synthesizes sized transistor schematics plications, our prototype implementation relies more heavily for simple CMOS operational amplifiers from performance on planning mechanisms than on rule execution. We attack specifications and process parameters, and demonstrates the the behavior-tc+structure portion of the synthesis task; our workability of the a.pproach. goal is to produce circuit schematics including device sizes, from performance specifications for common analog functional 1. Introduction blocks. This approach is motivated by the lack of tools to Design automation ideas from digital VLSI have only support the design of custom analog circuits. In particular, recently begun to migrate into analog circuit design. In part there are emerging semi-custom methodologies to lay out a this reflects the inherent complexities of the analog design given circuit schematic, but as yet no real tools to help design process. -

Design Thinking Methods and Techniques in Design Education

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ENGINEERING AND PRODUCT DESIGN EDUCATION 7 & 8 SEPTEMBER 2017, OSLO AND AKERSHUS UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF APPLIED SCIENCES, NORWAY DESIGN THINKING METHODS AND TECHNIQUES IN DESIGN EDUCATION Ana Paula KLOECKNER1, Cláudia de Souza LIBÂNIO1,2 and José Luis Duarte RIBEIRO1 1PPGEP/UFRGS, Brazil 2UFCSPA, Brazil ABSTRACT Design Thinking is a human-centred innovation process, with an emphasis on deep understanding of consumers, holistically, integratively, creatively, and awe-inspiring. Design Thinking methods and techniques represents how the theory will be operationalized by following the process steps. These methods and techniques can assist in the project management, especially in the initial phase of inspiration and ideation. Another strategy that can collaborate in project management is agile management, mainly in the execution phase of a project. Agile management prioritizes individuals, interactions between them, customers, appropriate software to operate, and prompt response to changes. Thus, this study aims to propose a model to integrate design thinking and project management methods and techniques and to analyze students’ projects and interactions to verify the applicability of these in ergonomic project management. For the development of the method, it was used the design science methodology, in four main steps called: Research Clarification, Descriptive Study I, Prescriptive Study, and Descriptive Study II. From the use of tools and techniques of design thinking in a project management exercise for students of two classes, it was revealed that the tools used facilitated the project development, helping from the search and organization of information until the deadline established for the delivery of the project. Keywords: Design Thinking, Design Education, Project Management. -

Understanding the Creative Mechanisms of Design Thinking: an Evolutionary Approach

!"#$%&'("#)"*+',$+-%$(').$+/$0,(")&1&+23+4$&)*"+5,)"6)"*7+ 8"+9.2:;')2"(%<+8==%2(0,+ Katja Thoring Roland M. Müller Department of Design Faculty of Business and Economics Anhalt University of Applied Sciences Berlin School of Economics and Law Seminarplatz 2a, 06846 Dessau/Germany Badensche Str. 50/51, 10825 Berlin/Germany +49 (0) 340 5197-1747 +49 (0) 30 85789-387 [email protected] [email protected] 8>?5@8-5+ Since generating creative concepts is one of the core aims In this article, we analyse the concept of design thinking of design thinking, we try to analyse how this is actually with its process, the team structure, the work environment, achieved. The first part of this article presents a short the specific culture, and certain brainstorming rules and overview of the design thinking process, as well as the techniques. The goal of this work is to understand how the involved artefacts and team members, and the underlying creative mechanisms of design thinking work and how they principles and guidelines for the process. In the second might be improved. For this purpose, we refer to the idea of section, we present an overview of the evolutionary theory creativity as an evolutionary process, which is determined of creativity. Both sections also cover the analysis of by generation (i.e., recombination and mutation), selection, existing literature in each area. The third section describes and retention of ideas. We evaluate the design thinking the used methodology, while in the fourth section, the main process in terms of its capabilities to activate these part of this article, we draw a comparison between the two mechanisms, and we propose possible improvements.