Opinion No. 07-67

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tennessee Valley Texas 1851 – 1951 Ann Joseph

Tennessee Valley Texas 1851 – 1951 Ann Joseph © 1986 by Ann Joseph All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America by Stillhouse Hollow Publishers Inc. P.O. Box 769, Temple, Texas 76503 DEDICATION This hook is dedicated to all those descendants who graciously shared their memories and photos of family and neighbor, to their ancestors whose courage and contributions inspired this modest memorial to the pioneer spirit, and to m y parents, Cecil and Mae Francis, whose love of the land and its people was passed on to their children. Austin, Texas August, 1985 Table of Contents FOREWORD ................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. THE SETTLEMENT: 1851 -1951............... Error! Bookmark not defined. ALLEN-DRAPER-HOWELL...................... Error! Bookmark not defined. BIGHAM ........................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. BIRDSONG ..................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. BOUNDS .......................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. CORNELISON - CROW - WHITELEY .. Error! Bookmark not defined. COX ................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. CRASS ................................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. EUBANKS ........................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. FRANCIS .......................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. -

Tennessee, 2015: Highlights

IWPR #R453 www.statusofwomendata. org The Status of Women in Tennessee, 2015: Highlights Women in Tennessee have made considerable advances in recent years but still face inequities that often prevent them from reaching their full potential. Since the 2004 Status of Women in the States report was published, the gender wage gap in Tennessee has narrowed, a higher percentage of women have bachelor’s degrees, and women are more likely to work in managerial or professional occupations. Yet, as in all other states, women in Tennessee are less likely than men to be in the labor force and more likely to live in poverty. Women also continue to be underrepresented in the state legislature. If current trends continue, women in Tennessee Women hold 17.4% will not see equal pay until the year 2057.* of seats in the state legislature. Key Findings Tennessee . Tennessee’s best grade is in the area of employment and earnings, for Report Card Summary which it receives a C-. Its worst grades are in health and well-being, Political Participation D- reproductive rights, and political participation, for which it gets a D-. Employment & Earnings C- . Tennessee women who work full-time, year-round earn 84 cents on the dollar compared with similarly employed men. Work & Family D . Approximately 30.1 percent of those working in science, technology, Poverty & Opportunity D engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields in Tennessee are women, compared with 28.8 percent nationwide. Reproductive Rights D- . As of 2015, there are no women of color from Tennessee in the U.S. Health & Well-Being D- Congress. -

State Abbreviations

State Abbreviations Postal Abbreviations for States/Territories On July 1, 1963, the Post Office Department introduced the five-digit ZIP Code. At the time, 10/1963– 1831 1874 1943 6/1963 present most addressing equipment could accommodate only 23 characters (including spaces) in the Alabama Al. Ala. Ala. ALA AL Alaska -- Alaska Alaska ALSK AK bottom line of the address. To make room for Arizona -- Ariz. Ariz. ARIZ AZ the ZIP Code, state names needed to be Arkansas Ar. T. Ark. Ark. ARK AR abbreviated. The Department provided an initial California -- Cal. Calif. CALIF CA list of abbreviations in June 1963, but many had Colorado -- Colo. Colo. COL CO three or four letters, which was still too long. In Connecticut Ct. Conn. Conn. CONN CT Delaware De. Del. Del. DEL DE October 1963, the Department settled on the District of D. C. D. C. D. C. DC DC current two-letter abbreviations. Since that time, Columbia only one change has been made: in 1969, at the Florida Fl. T. Fla. Fla. FLA FL request of the Canadian postal administration, Georgia Ga. Ga. Ga. GA GA Hawaii -- -- Hawaii HAW HI the abbreviation for Nebraska, originally NB, Idaho -- Idaho Idaho IDA ID was changed to NE, to avoid confusion with Illinois Il. Ill. Ill. ILL IL New Brunswick in Canada. Indiana Ia. Ind. Ind. IND IN Iowa -- Iowa Iowa IOWA IA Kansas -- Kans. Kans. KANS KS A list of state abbreviations since 1831 is Kentucky Ky. Ky. Ky. KY KY provided at right. A more complete list of current Louisiana La. La. -

METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT of NASHVILLE and DAVIDSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE V

12/16/2020 IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF TENNESSEE AT NASHVILLE September 2, 2020 Session METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT OF NASHVILLE AND DAVIDSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE v. CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION OF THE METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT OF NASHVILLE AND DAVIDSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE ET AL. Appeal from the Chancery Court for Davidson County No. 18-987-II Anne C. Martin, Chancellor ___________________________________ No. M2019-01587-COA-R3-CV ___________________________________ In this judicial review of an administrative decision, the trial court reversed the civil service commission’s decision to reinstate a police officer to his position upon finding that the commission’s reversal of the police department’s termination of the employee was arbitrary and capricious. The employee has appealed. Having determined that the findings of the civil service commission were supported by substantial and material evidence but that its ultimate decision was arbitrary and capricious, we affirm the judgment of the trial court reversing the commission’s decision. Tenn. R. App. P. 3 Appeal as of Right; Judgment of the Chancery Court Affirmed; Case Remanded THOMAS R. FRIERSON, II, J., delivered the opinion of the court, in which JOHN W. MCCLARTY and KRISTI M. DAVIS, JJ., joined. Kim C. Gilleland and Lisa G. Woolley, Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and Jack Byrd, Nashville, Tennessee, for the appellant, David Terrazas. Robert E. Cooper, Jr., and Allison L. Bussell, Nashville, Tennessee, for the appellee, Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County. OPINION I. Factual and Procedural History The respondent, David Terrazas, had been employed as a police officer with the Metropolitan Nashville Police Department (“MNPD”) for approximately eight years prior to his termination from that position. -

Tennessee Supreme Court Order Extending Limits on In-Person

03/25/2020 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE AT NASHVILLE IN RE: COVID-19 PANDEMIC ______________________ No. ADM2020-00428 ______________________ ORDER CONTINUING SUSPENSION OF IN-PERSON COURT PROCEEDINGS AND EXTENSION OF DEADLINES On March 13, 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chief Justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court declared a state of emergency for the Judicial Branch of Tennessee government and activated a Continuity of Operations Plan for the courts of Tennessee. See Tenn. Const. Art. VI, § 1; Tenn. Code Ann. §§ 16-3-501 to 16-3-504 (2009); Moore-Pennoyer v. State, 515 S.W.3d 271, 276-77 (Tenn. 2017); Tenn. Sup. Ct. R. 49. This state of emergency constitutes a “disaster” for purposes of Tenn. Sup. Ct. R. 49 and Tenn. Code Ann. § 28-1-116. In light of ongoing concerns, the Tennessee Supreme Court hereby continues the suspension of in-person court proceedings and the extension of deadlines as set forth in this order. We again emphasize that the local and state courts of the State of Tennessee are open and will remain open under all circumstances, subject to the provisions of this order. Under the constitutional, statutory, and inherent authority of the Tennessee Supreme Court, we adopt the following provisions. All in-person proceedings in all state and local courts in Tennessee, including but not limited to municipal, juvenile, general sessions, trial, and appellate courts, shall be suspended from the close of business on Friday, March 13, 2020, through Thursday, April 30, 2020, subject to the exceptions below. -

West Virginia Contractor License Tennessee - West Virginia Reciprocity Agreement Application

WEST VIRGINIA CONTRACTOR LICENSE TENNESSEE - WEST VIRGINIA RECIPROCITY AGREEMENT APPLICATION Please complete and forward this form to the West Virginia Contractor Licensing Board, 1900 Kanawha Boulevard East - State Capitol Complex - Building 3, Room 200 - Charleston, WV 25305 Email: [email protected] Telephone: (304) 558-7890 Facsimile: (304) 558-5174 (PLEASE TYPE OR PRINT CLEARLY) Current Tennessee Electrical Contractor License #: Current Tennessee General Building Contractor License #: Current Tennessee HVAC License #: Current Tennessee Masonry Contractor License #: Current Tennessee Multi-Family Contractor License #: Current Tennessee Plumbing Contractor License #: Current Tennessee Residential Contractor License #: Current Tennessee Sprinkler & Fire Protection Contractor License #: Exact Name In Which The Applicant's Tennessee Contractor License Is Issued: Mailing Address: City: State: Zip Code: Email Address: Name Of Person Who Qualified For Tennessee License By Passing The Required Examination Administered By The Tennessee Board for Licensing Contractors And The Date The Examination Was Passed: Name Date Qualified By Examination Was This License Issued Pursuant To An Agreement Between The Tennessee Board for Licensing Contractors And Another State? Yes: No: If Yes, Please List The State: Signature Title Date FOR TENNESSEE BOARD FOR LICENSING CONTRACTORS USE ONLY Confirmation by the Tennessee Board for Licensing Contractors that the above information provided by the Applicant for a West Virginia Contractor License is accurate. Signature Title Date Upon approval of this form, the applicant will be eligible to apply for a West Virginia Contractor License. Please visit labor.wv.gov to print forms. 12/17/2020. -

Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Great Smoky Mountains National Park

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Service National Park Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Resource Historic Park National Mountains Smoky Great Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 April 2016 VOL Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 1 As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historic places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration. GRSM 133/134404/A April 2016 GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 FRONT MATTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... -

A History of Tennessee.Indd

352 TENNESSEE BLUE BOOK A HISTORY OF TENNESSEE 353 SECTION VI Tennessee 354 TENNESSEE BLUE BOOK A HISTORY OF TENNESSEE 355 A HISTORY OF TENNESSEE The Land and Native People Tennessee’s great diversity in land, climate, rivers, and plant and animal life is mirrored by a rich and colorful past. For all but the last 200 years of the 12,000 years or so that this country has been inhabited, the story of Tennessee is the story of its native peoples. The fact that Tennessee and many of the places in it still carry Indian names serves as a lasting reminder of the significance of its native inhabit- ants. Since much of Tennessee’s appeal for her ancient people as well as for later pioneer settlers lay with the richness and beauty of the land, it seems fitting to begin by considering some of the state’s generous natural gifts. Tennessee divides naturally into three “grand divisions”—upland, often moun- tainous, East Tennessee, Middle Tennessee with its foothills and basin, and the low plain of West Tennessee. Travelers coming to the state from the east encounter first the lofty Unaka and Smoky Mountains, flanked on their western slope by the Great Valley of East Tennessee. Moving across the Valley floor, they next face the Cumberland Plateau, which historically attracted little settlement and presented a barrier to westward migration. West of the Plateau, one descends into the Cen- tral Basin of Middle Tennessee—a rolling, fertile countryside that drew hunters and settlers alike. The Central Basin is surrounded on all sides by the Highland Rim, the western ridge of which drops into the Tennessee River Valley. -

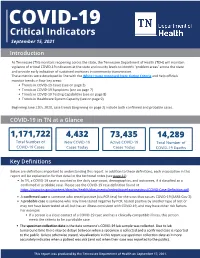

Critical Indicator Report

COVID-19 Critical Indicators September 15, 2021 Introduction As Tennessee (TN) monitors reopening across the state, the Tennessee Department of Health (TDH) will maintain vigilance of cri cal COVID-19 indicators at the state and county levels to iden fy ‘problem areas’ across the state and provide early indica on of sustained increases in community transmission. These metrics were developed in line with the White House proposed State Ga ng Criteria and help officials monitor trends in four key areas: • Trends in COVID-19 Cases (see on page 2) • Trends in COVID-19 Symptoms (see on page 7) • Trends in COVID-19 Tes ng Capabili es (see on page 8) • Trends in Healthcare System Capacity (see on page 9) Beginning June 12th, 2020, case trends (beginning on page 2) include both confirmed and probable cases. COVID-19 in TN at a Glance 1,171,722 4,432 73,435 14,289 Total Number of New COVID-19 Active COVID-19 Total Number of COVID-19 Cases Cases Today Cases Today COVID-19 Deaths Key Definitions Below are defini ons important to understanding this report. In addi on to these defini ons, each visuaiza on in this report will be explained in further detail in the technical notes (see page 11): • In TN, a COVID-19 case is counted in the daily case count, demographics, and outcomes, if it classified as a confirmed or probable case. Please see the COVID-19 case defini on found at h ps://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/health/documents/cedep/novel-coronavirus/COVID-Case-Defini on.pdf. -

Tennessee Texas

TENNESSEE COURSE AT MSU AS OF Austin Peay State Univ FIN 1000 - Personal Finance FIN 251 9/2/2015 East Tennessee State Univ MATH 1530-Prob/Stat Non-Calculus Math 210 2/12/2016 Nashville Community College, TNPST 1000 - Intro to CJ CJ 201 7/23/2013 Nashville Community College, TNPST 2000 - Drug Identification and Effects CJ Required Elective 7/23/2013 Pellissippi State CC Math 1010 - Survey of Math Math 102 10/30/2012 Pellissippi State CC Math 1530 - Elem Prob & Stat Math 210 10/30/2012 Pellissippi State CC SPH 2400 - Bus & Professional Spekaing Comm 110 10/30/2012 Southwest Tennessee CC MATH 1920-Calc & Analytic Geom II MATH 166 1/12/2016 Southwest Tennessee CC MATH 2110-Calc & Analytic Geom III MATH 265 1/12/2016 Univ of Tennessee-Knoxville BIOL 140-Organization & Function of a cell BIOL 150 12/4/2015 Univ of Tennessee-Knoxville ENGL 131-Comp/Non-Native Speakers of Eng ENGL 110 5/16/2016 Walers State ART 110 Basic Design I ART 122 3/25/2013 TEXAS COURSE AT MSU AS OF Angelina College ACCT 2301-Princ of Acct I ACCT 200 9/23/2013 Angelina College MSUCI 1306-Music Appreciation MUSC 100 9/3/2013 Angelo State Univ Hist 1302-Hist of US 1865-Pres Hist 104 7/15/2013 Central Texas College BUS 132-Bus & Professional Speaking COMM 110 1/12/2015 Central Texas College CJLE 1345 - Intermediate Crime Scene Inv CJ 226 7/23/2013 Central Texas College CJLE 1358 - Rights of Prisoners CJ Required Elective 7/23/2013 Central Texas College CJSA 1170 - Alcohol Awareness CJ Required Elective 7/23/2013 Central Texas College CJSA 1318 - Court Management CJ Required -

Geologic Map of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park Region, Tennessee and North Carolina

Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Geologic Map of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park Region, Tennessee and North Carolina By Scott Southworth, Art Schultz, John N. Aleinikoff, and Arthur J. Merschat Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 2997 Supersedes USGS Open-File Reports 03–381, 2004–1410, and 2005–1225 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Southworth, Scott, Schultz, Art, Aleinikoff, J.N., and Merschat, A.J., 2012, Geologic map of the Great Smoky Moun- tains National Park region, Tennessee and North Carolina: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 2997, one sheet, scale 1:100,000, and 54-p. pamphlet. (Supersedes USGS Open-File Reports 03–381, 2004–1410, and 2005–1225.) ISBN 978-1-4113-2403-9 Cover: Looking northeast toward Mount Le Conte, Tenn., from Clingmans Dome, Tenn.-N.C. -

The New Deal in East Tennessee

The New Deal in East Tennessee Grade Level: 5th & 11th Grade Standards/Unit: 5th Grade Unit 4: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945) Local I.D. #: 5.4.03: Explain how the New Deal addressed social and economic programs caused by the Great Depression (i.e. Social security, FDIC, CCC, WPA, PWA.) Local I.D. #5.4.04: Analyze the impact of TVA on the Tennessee valley (i.e. loss of land, flood control, electric power.) 11th Grade Unit 3: Roaring Twenties through the Great Depression Local I.D. #3.02: Identify New Deal Programs/Initiatives (i.e. Social Security, WPA, TVA, Indian Reorganization Act, FDIC, CCC, Wagner/Fair Labor Standards’ Act). Lesson Time: One class period Objective/Purpose: Students will understand the local historic significance of the New Deal in Knoxville and the surrounding area and be able to locate historic structures and places that were associated with the New Deal in East Tennessee. Materials: PowerPoint Strategies/Procedures: Teachers will present the PowerPoint and then engage the students in a discussion using the following question(s). If time allows you may use one question or all. 1. Describe the objectives of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and how it impacted the Smoky Mountains. 2. If you were a CCC worker assigned to work in the Smoky Mountains what job assignment would you like and why? 3. What two buildings were used as the first headquarters for TVA and why do you think downtown Knoxville selected as the headquarters for the TVA? 4. What was the first major project for the Tennessee Valley Authority? Activities: if time permits teachers can assign in-class enrichment projects for extra credit.