Stroke Volume Variation “Can We Use Fluid to Improve Hemodynamics?”

Total Page:16

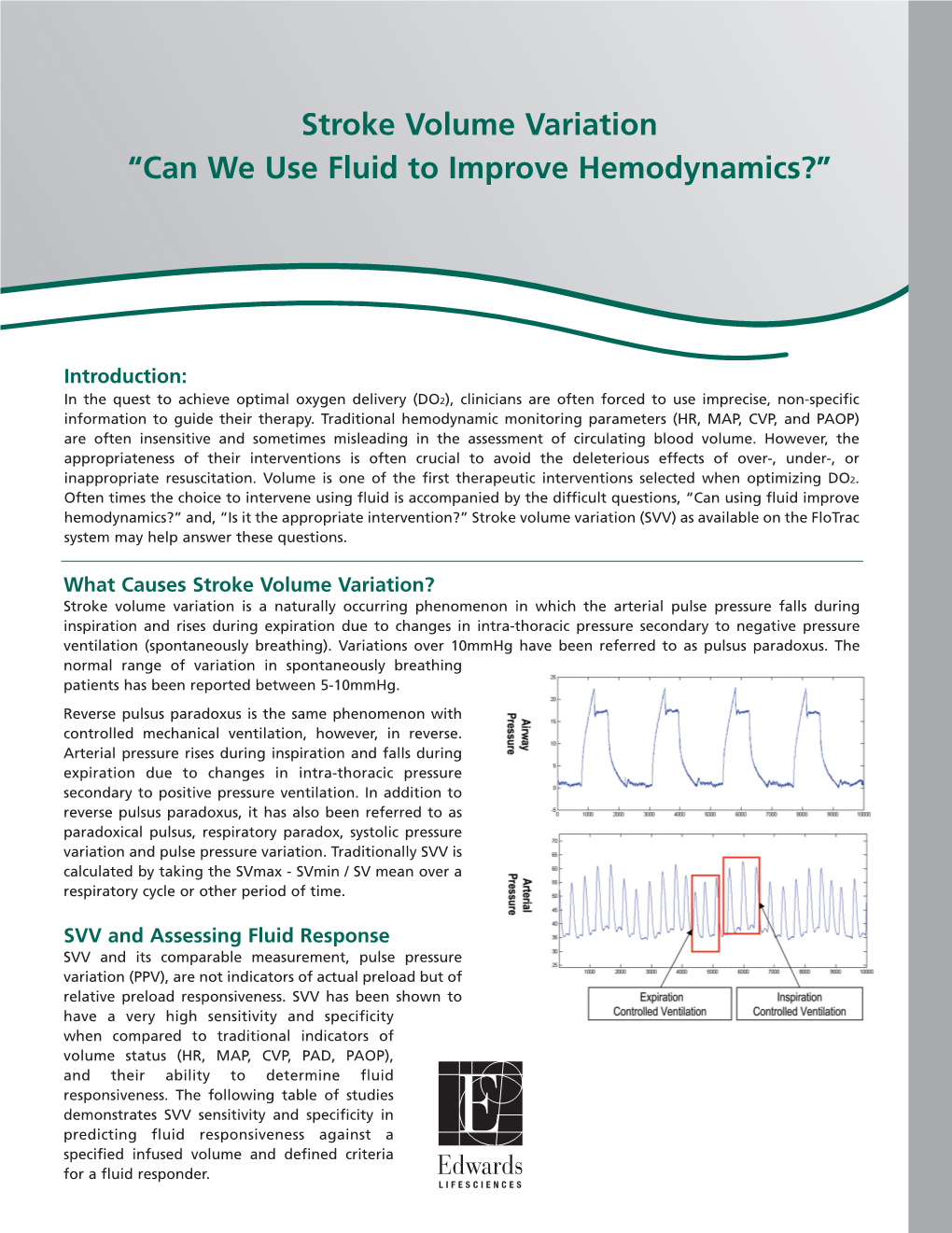

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Venous Pressure: Uses and Limitations

Central Venous Pressure: Uses and Limitations T. Smith, R. M. Grounds, and A. Rhodes Introduction A key component of the management of the critically ill patient is the optimization of cardiovascular function, including the provision of an adequate circulating volume and the titration of cardiac preload to improve cardiac output. In spite of the appearance of several newer monitoring technologies, central venous pressure (CVP) monitoring remains in common use [1] as an index of circulatory filling and of cardiac preload. In this chapter we will discuss the uses and limitations of this monitor in the critically ill patient. Defining Central Venous Pressure What is the Central Venous Pressure? Central venous pressure is the intravascular pressure in the great thoracic veins, measured relative to atmospheric pressure. It is conventionally measured at the junction of the superior vena cava and the right atrium and provides an estimate of the right atrial pressure. The Central Venous Pressure Waveform The normal CVP exhibits a complex waveform as illustrated in Figure 1. The waveform is described in terms of its components, three ascending ‘waves’ and two descents. The a-wave corresponds to atrial contraction and the x descent to atrial relaxation. The c wave, which punctuates the x descent, is caused by the closure of the tricuspid valve at the start of ventricular systole and the bulging of its leaflets back into the atrium. The v wave is due to continued venous return in the presence of a closed tricuspid valve. The y descent occurs at the end of ventricular systole when the tricuspid valve opens and blood once again flows from the atrium into the ventricle. -

Cardiovascular Physiology

CARDIOVASCULAR PHYSIOLOGY Ida Sletteng Karlsen • Trym Reiberg Second Edition 15 March 2020 Copyright StudyAid 2020 Authors Trym Reiberg Ida Sletteng Karlsen Illustrators Nora Charlotte Sønstebø Ida Marie Lisle Amalie Misund Ida Sletteng Karlsen Trym Reiberg Booklet Disclaimer All rights reserved. No part oF this book may be reproduced in any Form on by an electronic or mechanical means, without permission From StudyAid. Although the authors have made every efFort to ensure the inFormation in the booklet was correct at date of publishing, the authors do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any part For any inFormation that is omitted or possible errors. The material is taken From a variety of academic sources as well as physiology lecturers, but are Further incorporated and summarized in an original manner. It is important to note, the material has not been approved by professors of physiology. All illustrations in the booklet are original. This booklet is made especially For students at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow by tutors in the StudyAid group (students at JU). It is available as a PDF and is available for printing. If you have any questions concerning copyrights oF the booklet please contact [email protected]. About StudyAid StudyAid is a student organization at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. Throughout the academic year we host seminars in the major theoretical subjects: anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, immunology, pathophysiology, supplementing the lectures provided by the university. We are a group of 25 tutors, who are students at JU, each with their own Field oF specialty. To make our seminars as useful and relevant as possible, we teach in an interactive manner often using drawings and diagrams to help students remember the concepts. -

Effects of Vasodilation and Arterial Resistance on Cardiac Output Aliya Siddiqui Department of Biotechnology, Chaitanya P.G

& Experim l e ca n i t in a l l C Aliya, J Clinic Experiment Cardiol 2011, 2:11 C f a Journal of Clinical & Experimental o r d l DOI: 10.4172/2155-9880.1000170 i a o n l o r g u y o J Cardiology ISSN: 2155-9880 Review Article Open Access Effects of Vasodilation and Arterial Resistance on Cardiac Output Aliya Siddiqui Department of Biotechnology, Chaitanya P.G. College, Kakatiya University, Warangal, India Abstract Heart is one of the most important organs present in human body which pumps blood throughout the body using blood vessels. With each heartbeat, blood is sent throughout the body, carrying oxygen and nutrients to all the cells in body. The cardiac cycle is the sequence of events that occurs when the heart beats. Blood pressure is maximum during systole, when the heart is pushing and minimum during diastole, when the heart is relaxed. Vasodilation caused by relaxation of smooth muscle cells in arteries causes an increase in blood flow. When blood vessels dilate, the blood flow is increased due to a decrease in vascular resistance. Therefore, dilation of arteries and arterioles leads to an immediate decrease in arterial blood pressure and heart rate. Cardiac output is the amount of blood ejected by the left ventricle in one minute. Cardiac output (CO) is the volume of blood being pumped by the heart, by left ventricle in the time interval of one minute. The effects of vasodilation, how the blood quantity increases and decreases along with the blood flow and the arterial blood flow and resistance on cardiac output is discussed in this reviewArticle. -

Time-Varying Elastance and Left Ventricular Aortic Coupling Keith R

Walley Critical Care (2016) 20:270 DOI 10.1186/s13054-016-1439-6 REVIEW Open Access Left ventricular function: time-varying elastance and left ventricular aortic coupling Keith R. Walley Abstract heart must have special characteristics that allow it to respond appropriately and deliver necessary blood flow Many aspects of left ventricular function are explained and oxygen, even though flow is regulated from outside by considering ventricular pressure–volume characteristics. the heart. Contractility is best measured by the slope, Emax, of the To understand these special cardiac characteristics we end-systolic pressure–volume relationship. Ventricular start with ventricular function curves and show how systole is usefully characterized by a time-varying these curves are generated by underlying ventricular elastance (ΔP/ΔV). An extended area, the pressure– pressure–volume characteristics. Understanding ventricu- volume area, subtended by the ventricular pressure– lar function from a pressure–volume perspective leads to volume loop (useful mechanical work) and the ESPVR consideration of concepts such as time-varying ventricular (energy expended without mechanical work), is linearly elastance and the connection between the work of the related to myocardial oxygen consumption per beat. heart during a cardiac cycle and myocardial oxygen con- For energetically efficient systolic ejection ventricular sumption. Connection of the heart to the arterial circula- elastance should be, and is, matched to aortic elastance. tion is then considered. Diastole and the connection of Without matching, the fraction of energy expended the heart to the venous circulation is considered in an ab- without mechanical work increases and energy is lost breviated form as these relationships, which define how during ejection across the aortic valve. -

Passive Leg Raising: Five Rules, Not a Drop of Fluid! Xavier Monnet1,2* and Jean-Louis Teboul1,2

Monnet and Teboul Critical Care (2015) 19:18 DOI 10.1186/s13054-014-0708-5 EDITORIAL Open Access Passive leg raising: five rules, not a drop of fluid! Xavier Monnet1,2* and Jean-Louis Teboul1,2 In acute circulatory failure, passive leg raising (PLR) is a Third, the technique used to measure cardiac output test that predicts whether cardiac output will increase during PLR must be able to detect short-term and tran- with volume expansion [1]. By transferring a volume of sient changes since the PLR effects may vanish after around 300 mL of venous blood [2] from the lower body 1 minute [1]. Techniques monitoring cardiac output in toward the right heart, PLR mimics a fluid challenge. ‘real time’, such as arterial pulse contour analysis, echo- However, no fluid is infused and the hemodynamic effects cardiography, esophageal Doppler, or contour analysis of are rapidly reversible [1,3], thereby avoiding the risks of the volume clamp-derived arterial pressure, can be used fluid overload. This test has the advantage of remaining [6]. Conflicting results have been reported for bioreac- reliable in conditions in which indices of fluid responsive- tance [7,8]. The hemodynamic response to PLR can even ness that are based on the respiratory variations of stroke be assessed by the changes in end-tidal exhaled carbon volume cannot be used [1], like spontaneous breathing, dioxide, which reflect the changes in cardiac output in arrhythmias, low tidal volume ventilation, and low lung the case of constant minute ventilation [5]. compliance. Fourth, cardiac output must be measured not only The method for performing PLR is of the utmost before and during PLR but also after PLR when the importance because it fundamentally affects its hemody- patient has been moved back to the semi-recumbent namic effects and reliability. -

Assessing Cardiac Preload by the Initial Systolic Time Interval Obtained from Impedance Cardiography

J Electr Bioimp, vol. 1, pp. 80–83, 2010 Received: 4 Nov 2010, published: 10 Dec 2010 http://dx.doi.org/10.5617/jeb.141 Assessing cardiac preload by the Initial Systolic Time Interval obtained from impedance cardiography Jan H. Meijer 1,3, Annemieke Smorenberg 2, Erik J. Lust 2, Rudolf M. Verdaasdonk 1 and A. B. Johan Groeneveld 2 1. Department of Physics and Medical Technology, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands 2. Department of Intensive Care for Adults, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands 3. E-mail any correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract cardiac cycle [2], while the ECG reflects the electrical The Initial Systolic Time Interval (ISTI), obtained from the aspect of the heart. Therefore, the time difference between electrocardiogram (ECG) and impedance cardiogram (ICG), is specific moments in the two signals can be interpreted as considered to be a measure for the time delay between the the time difference between the electrical and mechanical electrical and mechanical activity of the heart and reflects an early activity of the heart and may contain valuable clues about active period of the cardiac cycle. The clinical relevance of this time interval is subject of study. This paper introduces a method the functioning of the heart, also as controlled by the using ISTI to evaluate and predict the circulatory response to fluid autonomic nervous system, and the condition of the administration in patients after coronary artery bypass graft circulation. Both ECG and ICG signals can be obtained fast surgery and presents preliminary results of a pilot study by and easily. -

Cardiac Preload Evaluation Using Echocardiographic Techniques

Cardiac Preload Evaluation Using Echocardiographic Techniques M. Slama Introduction For many decades, central venous (CVP) pulmonary artery occlusion pressures (PAOP), assumed to reflect of right and left filling pressures, respectively, have been used to assess right and left cardiac preload. Although they are obtained from invasive catheterization, they are still used by a lot of physicians in their fluid infusion decision making process [1]. Many approaches have been proposed to assess preload using non-invasive techniques. Echocardiography and cardiac Doppler have been extensively used in the cardiologic field but have taken time to be widely used in the intensive care unit (ICU). However, echocardiography is now considered by most European ICU physicians as the first line method to evaluate cardiac function in patients with hemodynamic instability, not only in terms of diagnosis but also in terms of the therapeutic decision making process [2–3]. Regarding cardiac preload and cardiac preload reserve, cardiac echo-Dop- pler can provide important information. Echocardiographic Indices Vena Cava Size and Size Changes The inferior vena cava is a highly compliant vessel that changes its size with changes in CVP. The inferior vena cava can be visualized using transthoracic echocardiography. Short axis or long axis views from a sub costal view are used to measure the diameter or the area of this vessel [4]. For a long time, attempts were made to estimate CVP from measurements of inferior vena caval dimensions. Because of the complex relationship between CVP, right heart function, blood volume, and intrathoracic pressures, divergent results were reported depending on the disease category of patients, the timing in measurement in the respiratory cycle, the presence of significant tricuspid regurgitation, etc. -

JUGULAR VENOUS PRESSURE Maddury Jyotsna

INDIAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES JOURNAL in women (IJCD) 2017 VOL 2 ISSUE 2 CLINICAL ROUNDS 1 WINCARS JVP- JUGULAR VENOUS PRESSURE Maddury Jyotsna DEFINITION OF JUGULAR VENOUS PULSE AND The external jugular vein descends from the angle of the PRESSURE mandible to the middle of the clavicle at the posterior Jugular venous pulse is defined as the oscillating top of border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The external vertical column of blood in the right Internal Jugular jugular vein possesses valves that are occasionally Vein (IJV) that reflects the pressure changes in the right visible. Blood flow within the external jugular vein is atrium in cardiac cycle. In other words, Jugular venous nonpulsatile and thus cannot be used to assess the pressure (JVP) is the vertical height of oscillating column contour of the jugular venous pulse. of blood (Fig 1). Reasons for Internal Jugular Vein (IJV) preferred over Fig 1: Schematic diagram of JVP other neck veins are IJV is anatomically closer to and has a direct course to right atrium while EJV does not directly drain into Superior vena cava. It is valve less and pulsations can be seen. Due to presence of valves in External Jugular vein, pulsations cannot be seen. Vasoconstriction secondary to hypotension (as in congestive heart failure) can make EJV small and barely visible. EJV is superficial and prone to kinking. Partial compression of the left in nominate vein is usually relieved during modest inspiration as the diaphragm and the aorta descend and the pressure in the two internal -

Chapter 9 Monitoring of the Heart and Vascular System

Chapter 9 Monitoring of the Heart and Vascular System David L. Reich, MD • Alexander J. Mittnacht, MD • Martin J. London, MD • Joel A. Kaplan, MD Hemodynamic Monitoring Cardiac Output Monitoring Arterial Pressure Monitoring Indicator Dilution Arterial Cannulation Sites Analysis and Interpretation Indications of Hemodynamic Data Insertion Techniques Systemic and Pulmonary Vascular Resistances Central Venous Pressure Monitoring Frank-Starling Relationships Indications Monitoring Coronary Perfusion Complications Electrocardiography Pulmonary Arterial Pressure Monitoring Lead Systems Placement of the Pulmonary Artery Catheter Detection of Myocardial Ischemia Indications Intraoperative Lead Systems Complications Arrhythmia and Pacemaker Detection Pacing Catheters Mixed Venous Oxygen Saturation Catheters Summary References HEMODYNAMIC MONITORING For patients with severe cardiovascular disease and those undergoing surgery associ- ated with rapid hemodynamic changes, adequate hemodynamic monitoring should be available at all times. With the ability to measure and record almost all vital physi- ologic parameters, the development of acute hemodynamic changes may be observed and corrective action may be taken in an attempt to correct adverse hemodynamics and improve outcome. Although outcome changes are difficult to prove, it is a rea- sonable assumption that appropriate hemodynamic monitoring should reduce the incidence of major cardiovascular complications. This is based on the presumption that the data obtained from these monitors are interpreted correctly and that thera- peutic decisions are implemented in a timely fashion. Many devices are available to monitor the cardiovascular system. These devices range from those that are completely noninvasive, such as the blood pressure (BP) cuff and ECG, to those that are extremely invasive, such as the pulmonary artery (PA) catheter. To make the best use of invasive monitors, the potential benefits to be gained from the information must outweigh the potential complications. -

Drugs That Affect the Cardiovascular System

PharmacologyPharmacologyPharmacology DrugsDrugs thatthat AffectAffect thethe CardiovascularCardiovascular SystemSystem TopicsTopicsTopics •• Electrophysiology Electrophysiology •• Vaughn-Williams Vaughn-Williams classificationclassification •• Antihypertensives Antihypertensives •• Hemostatic Hemostatic agentsagents CardiacCardiacCardiac FunctionFunctionFunction •• Dependent Dependent uponupon –– Adequate Adequate amountsamounts ofof ATPATP –– Adequate Adequate amountsamounts ofof CaCa++++ –– Coordinated Coordinated electricalelectrical stimulusstimulus AdequateAdequateAdequate AmountsAmountsAmounts ofofof ATPATPATP •• Needed Needed to:to: –– Maintain Maintain electrochemicalelectrochemical gradientsgradients –– Propagate Propagate actionaction potentialspotentials –– Power Power musclemuscle contractioncontraction AdequateAdequateAdequate AmountsAmountsAmounts ofofof CalciumCalciumCalcium •• Calcium Calcium isis ‘glue’‘glue’ that that linkslinks electricalelectrical andand mechanicalmechanical events.events. CoordinatedCoordinatedCoordinated ElectricalElectricalElectrical StimulationStimulationStimulation •• Heart Heart capablecapable ofof automaticityautomaticity •• Two Two typestypes ofof myocardialmyocardial tissuetissue –– Contractile Contractile –– Conductive Conductive •• Impulses Impulses traveltravel throughthrough ‘action‘action potentialpotential superhighway’.superhighway’. A.P.A.P.A.P. SuperHighwaySuperHighwaySuperHighway •• Sinoatrial Sinoatrial node node •• Atrioventricular Atrioventricular nodenode •• Bundle Bundle ofof -

ECG Workshop the Fundamentals

ECG Workshop The Fundamentals Darrell E. Jones, DO David Kassop, MD, FACC ACTIVITY DISCLAIMER The material presented here is being made available by the American Academy of Family Physicians for educational purposes only. Please note that medical information is constantly changing; the information contained in this activity was accurate at the time of publication. This material is not intended to represent the only, nor necessarily best, methods or procedures appropriate for the medical situations discussed. Rather, it is intended to present an approach, view, statement, or opinion of the faculty, which may be helpful to others who face similar situations. The AAFP disclaims any and all liability for injury or other damages resulting to any individual using this material and for all claims that might arise out of the use of the techniques demonstrated therein by such individuals, whether these claims shall be asserted by a physician or any other person. Physicians may care to check specific details such as drug doses and contraindications, etc., in standard sources prior to clinical application. This material might contain recommendations/guidelines developed by other organizations. Please note that although these guidelines might be included, this does not necessarily imply the endorsement by the AAFP. DISCLOSURE It is the policy of the AAFP that all individuals in a position to control content disclose any relationships with commercial interests upon nomination/invitation of participation. Disclosure documents are reviewed for potential conflict of interest (COI), and if identified, conflicts are resolved prior to confirmation of participation. Only those participants who had no conflict of interest or who agreed to an identified resolution process prior to their participation were involved in this CME activity. -

Navigating Preload Assessment

NAVIGATING PRELOAD ASSESSMENT CHOOSING THE RIGHT PATHWAY Cecilia Baylon & Sarah Neville LEARNING OBJECTIVES • Explain the relationship between preload and fluid responsiveness (FR) • Review the different methods of assessing preload and FR • Analyze the current research in regard to their use in the critical care setting O2 demand CARDIAC OUTPUT Respiratory Lung Muscle Compliance Patient’s Venous Vessel Diameter Function Pre-existing Alveoli Return (Peripheral Medical Perfused? Vascular Condition Blood Work of Resistance) Viscosity Breathing Total Alveoli Thickness of Circulating Ventilated? Alveolar-Capillary Membrane Volume Aortic Physical Tidal Volume etc Impedence Activity Respiratory Vital Capacity Rate Functional Resid. Capac V/Q Emotional Diffusion pH, PC02 Matching Contractility Preload Temperature Stress 2,3 DPG Afterload Ventilation ie: pain PaCO2 Oxygen ALVEOLAR Hgb Hgb Level GAS EXCHANGE Affinity METABOLIC STROKE HEART RATE DEMANDS Pa02 Oxygen VOLUME ARTERIAL OXYGEN transported SATURATION in blood Sa02 ARTERIAL OXYGEN CARDIAC OUTPUT CONTENT OXYGEN OXYGEN SUPPLY DEMAND BALANCE End organ perfusion OXYGEN SUPPLY & DEMAND (HEMODYNAMIC) FRAMEWORK CONTRACTILITY PRELOAD AFTERLOAD STROKE VOLUME X HEART RATE CARDIAC OUTPUT EOP FRANK-STARLING’S LAW FRANK-STARLING’S LAW • “the force of ventricular ejection is directly related to…” VOLUME IN THE VENTRICLE AT END-DIASTOLE (PRELOAD) AMOUNT OF MYOCARDIAL STRETCH PLACED ON THE VENTRICLE AS A RESULT Urden, Stacy, Lough (2018), p. 214 Ejection Phase Hyperinotropy Contractility Norminotropy