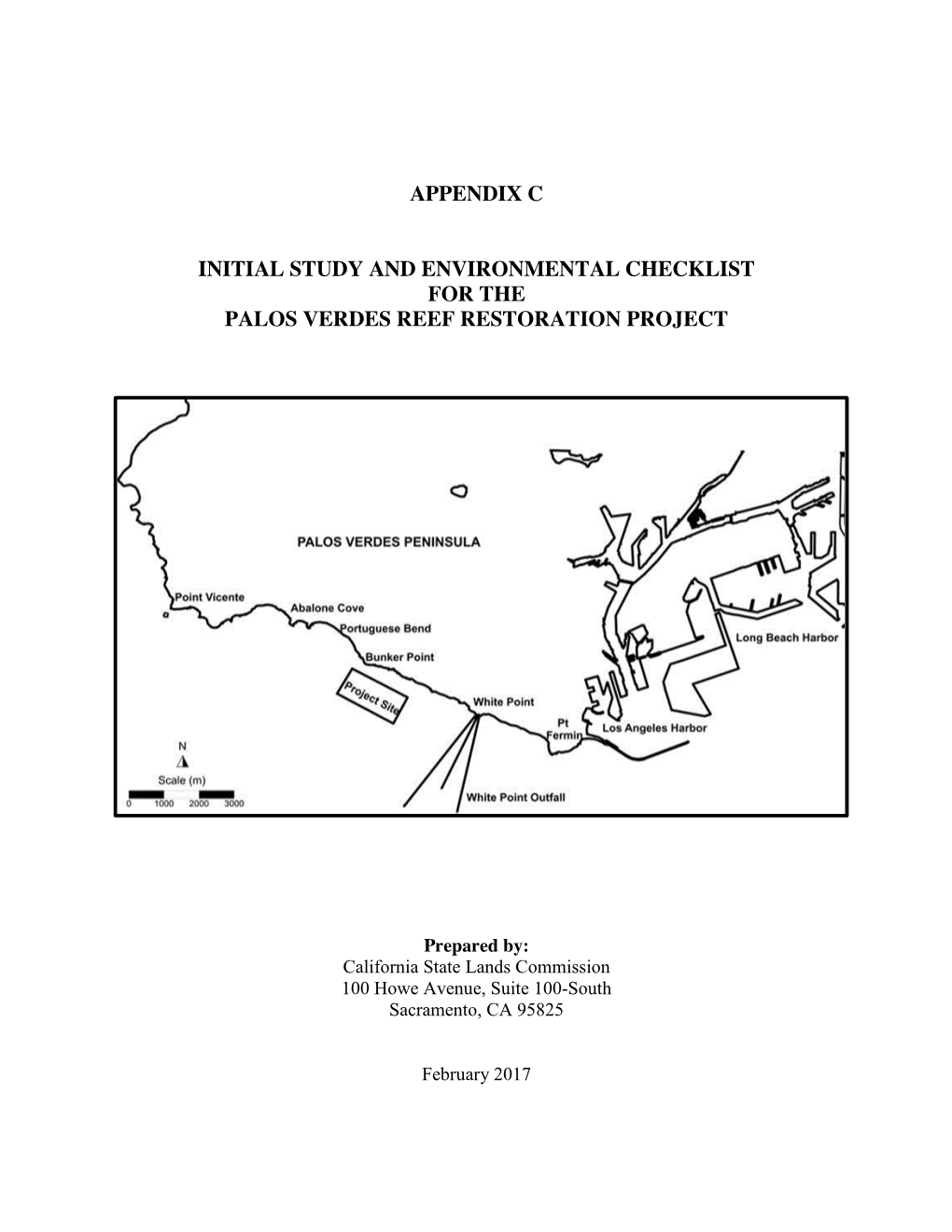

Initial Study and Environmental Checklist for the Palos Verdes Reef Restoration Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presented By

RESOLUTION WHEREAS, July 19, 2013 marks the 10th anniversary of the opening of the Port of Los Angeles Waterfront Red Car Line, and WHEREAS, since :its opening on July 19, 2003, the Waterfront Red Car Line has carried nearly one millionpassengers, and WHEREAS, the Waterfront Red Car Line was the first major project to be completed on the San Pedro Waterfront, which now includes the Waterfront Promenade, the Gateway Plaza Fanfare Fountains, the USS IOWA battleship, CRAFTED at the Port of Los Angeles and the Cabrillo Way Marina, and will soon include a new downtown harbor development and a revitalized Ports O'Call Village, and WHEREAS, when the Waterfront Red Car line opened in July, 2003 :itwas the first time that Red Cars had roo in Los Angeles in over 40 years, and WHEREAS, Waterfront Red Cars 500 and 501 are exact replicas of the original Pacific Electric Red Cars that ran to San Pedro in the 1920's, and WHEREAS, Waterfront Red Cars 500 and 501 were constructed using the immense skills and talents of the crafts persons of the Harbor Department's Construction and Maintenance Division, and WHEREAS, the Waterfront Red Cars operate Friday through Sunday every week of the year and are a particularly important transportation link during Port of Los Angeles special events, carrying hundreds ofvis:itors to the Cars and Stripes July 4th event, the Summer Concerts at the fountains and the Port of Los Angeles Lobster Festival, and WHEREAS, the Waterfront Red Cars offer a "trip back in time" to those people who remember the original Red Cars and to those who want to learn about Los Angeles history, and also provide a :fun trolley ride for children of all ages, NOW, 1HEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED, that by adoption of this resolution, the Los Angeles C:ityCouncil, along with the Mayor, hereby commemorates the 10th anniversary ofthe opening of the Port of Los Angeles Waterfront Red Car Line and sends its heartfelt congratulations on this momentous occasion. -

Federal Transit Administration

Finding of No Significant Impact Grant Applicant: City of Los Angeles Project: Restoration of Historic Streetcar Service in Downtown Los Angeles Project Location: City of Los Angeles, California The Environmental Assessment (EA) for the Restoration of Historic Streetcar Service in Downtown Los Angeles (Project) was prepared in cooperation with the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969 (42 United States Code [U.S.C.] 4332); the Federal Transit Laws (49 U.S.C. 5301(e), 5323(b), and 5324(b)); Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act of 1966 (49 U.S.C. 303); and Executive Order 12898 (Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations). FTA is the federal lead agency for the Project under the NEPA. Development of the Project and its environmental review process are being managed through the joint cooperation of the City of Los Angeles (City) Department of Transportation (LADOT), Bureau of Engineering (LABOE), and the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro). Additional support is being provided by City Council District 14 and Los Angeles Streetcar Inc. (LASI), an independent non-profit agency. The Project will be constructed in accordance with the design features and mitigation measures presented in the EA. The full text of the EA, prepared by the City of Los Angeles and approved and issued by FTA, is hereby incorporated by reference in this Finding of No Significant Impact. PROJECT DESCRIPTION The Project proposes to enhance mobility options to residents, employees and visitors of downtown Los Angeles through expanded transit circulation service and as well as support the growth and revitalization of downtown Los Angeles. -

BULLETIN BOARD Metrolink Leases Cars MEMBERS in ACTION

BULLETIN BOARD The member site links page of our website is being updated, so anyone who would like Our Jan. 10th meeting will be held in the their transit-related website included send auditorium adjacent to our usual meeting the URL to [email protected]. If anyone space. The guest speaker is Alan Mittel• needs a password reset for access to the staedt, formerly the news editor of the L.A. member board, send to the aforementioned Weekly and L.A. CityBeat. His presentation e-mail address your login name and choice will begin at 1 p.m. After the meeting, an of password. ad-hoc committee will meet to discuss pro• posed service changes by Metro and deter• The environmental documents for the pro• mine So.CA.TA's official positions on them. posed extension of the Orange Line along The speaker at our Feb. meeting will be Co• Canoga are posted on the Metro web- nan Cheung, Deputy Executive Officer for site: http://metro. net/projects_studies/ Operations Service Planning and Develop• canoga_corridor /meeti ngs. htm ment at Metro. Fixing Angelinos Stuck in Traffic (FAST) is a The annual holiday banquet held this year non-profit working to implement the recent at Clifton's Cafeteria was a rousing success. RAND report on reducing congestion: Trinkets and door prizes were donated http://www.fastla.org/ ~. ~ ~ by Culver CityBus, MTS, Gold Coast Transit, Torrance Transit, Caltrans Division of Rail, Omnitrans, Santa Monica Big Blue Bus. MEMBERS IN ACTION Foothill Transit and Metro plus Steve Cromser, Dana Gabbard, Dave Snowden, Ken Ruben attended the Metro Westside Carlos Osuna and Mark Strickert. -

January 2016 Board Meeting

Los Angeles County Metro Metropolitan Transportation Authority One Gateway Plaza 3rd Floor Board Room Board Report Los Angeles, CA File #:2015-1662, File Type:Informational Report Agenda Number:62. REGULAR BOARD MEETING JANUARY 28, 2016 SUBJECT: SAN PEDRO RED CAR LINE MOTION RESPONSE ACTION: RECEIVE AND FILE RECOMMENDATION RECEIVE AND FILE response to Motion #39 in September 2015 by Director Knabe on the San Pedro Red Car Line. ISSUE In September 2015, a motion by Director Don Knabe (Attachment A) directed the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) to report on items related to the operations of the San Pedro Red Car Line. DISCUSSION A 1990s study of the San Pedro waterfront envisioned significant development along the waterfront, from the Catalina and World Cruise Terminals on the north to Ports O’ Call Village and the 22nd St. / East Channel / West Channel / Los Angeles Harbor on the south. One of the components of this study was for a rail line to operate between the locations. In turn, the Port of Los Angeles (POLA) opened the 1.5 mile Waterfront Red Car Line on July 19, 2003 with four high platform stations serving the World Cruise Center, Downtown San Pedro, Ports O’ Call, and the Marina. Initial operation provided regular service Fridays thru Mondays, using two trolleys from 10am to 6pm and on days when cruise ships were in Port. In 2010, regular service was reduced to Fridays thru Sundays using one trolley car, operating from 12pm to 9pm with a $1 fare for the entire day and free during special events. Findings From 2005 through 2009, annual ridership was reported to have about 103,000 passengers on average. -

2013 Logistics Planner | Digital Edition

SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT LOGISTICS PLANNER f the “new normal” has taught industry anything, it’s that flexibility is compul- sory in today’s environment. Everywhere you look, forces at play threaten to tip the scales and derail even the most resilient supply chains. Whether it’s accounting for potential labor strife, insulating against natural disasters, confronting regulatory barriers, accessing capacity, or managing inven- tory against uncertain demand, shippers are challenged with finding balance within their organization as they optimize their cost-to-serve. Partnering with the right carrier, technology or logistics provider is one important way you can marshal your supply chain to act as a force equalizer – multiplier even – and tackle these challenges head-on while enhancing velocity and service to your customers. Logistics practitioners turn to transportation and logistics intermediaries for countless rea- sons: to variabilize cost structures, divest non-core business functions, execute supply chain strategies, avert risk, tap new technologies, and manage growth without capital investment. In different ways, supply chain partners can help you replace inventory with information, increase visibility, and more effectively match demand signals to supply. January 2013 • Inbound Logistics 335 This year’s Logistics Planner features an exclusive group of com- segment, type of solutions provided, and more. A number of com- panies across all areas of the supply chain. These “force multipliers” panies have included corporate videos so be sure to check out their have the requisite tools and expertise to aggregate and align your sup- multimedia profiles. ply chain management efforts with go-to-market strategies. They can If you want to download the entire Logistics Planner, point and help create synergies within your transportation and logistics func- click your way to inboundlogistics.com/digital. -

MTA Report May 2003

metro.net: Archives Metro Report Archives May 2003 Articles MTA Report Bulletin Board MTA to Increase Schedule for Metro Gold Line Testing (May 30, 2003) In preparation for the opening of the Metro Gold Line this summer, MTA has begun increased operational testing from Union Station in Los Angeles to Sierra Madre Villa Station in Pasadena. LASD Fare Inspectors Now Aboard Metro Rail (May 29, 2003) Fare inspectors have been deployed on the Metro Red Line this week under a partnership between MTA and the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department to supplement law enforcement on Metro Rail. Transit Police Chief Urges Employees to be Alert (May 28, 2003) With the nation’s terrorist threat alert level now set at “Orange,” Transit Police Chief Dan Finkelstein is asking MTA employees to “maintain a heightened interest in their surroundings.” UPDATE: FY-04 Budget, Fare Restructuring Approved at May Board Meeting Memorial Service Set, May 28, for SCRTD’s John Dyer (May 22, 2003) A memorial service celebrating the life of former SCRTD General Manager John A. Dyer is scheduled Wednesday, May 28. Paleontologists Unearth Mammoth Tusk Fossil on MTA Property (May 21, 2003) Paleontologists working on MTA property have unearthed a small section of a mammoth tusk approximately 10,000 to 70,000 years old. MTA has donated the fossil, which is believed to date to the late Pleistocene era, to the Museum of Natural History of Los Angeles County for study and preservation. FY-04 Budget, Fare Restructuring Lead May Board Agenda (May 20, 2003) Adoption of the FY 2004 budget and a motion to restructure Metro fares for the first time in eight years are likely to dominate Thursday’s MTA Board meeting, but there are other items of interest on the agenda. -

San Pedro Red Car Line Motion Response Action: Receive and File

Los Angeles County Metro Metropolitan Transportation Authority One Gateway Plaza 3rd Floor Board Room Board Report Los Angeles, CA File #: 2015-1662, File Type: Informational Report Agenda Number: 62. REGULAR BOARD MEETING JANUARY 28, 2016 SUBJECT: SAN PEDRO RED CAR LINE MOTION RESPONSE ACTION: RECEIVE AND FILE RECOMMENDATION RECEIVE AND FILE response to Motion #39 in September 2015 by Director Knabe on the San Pedro Red Car Line. ISSUE In September 2015, a motion by Director Don Knabe (Attachment A) directed the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) to report on items related to the operations of the San Pedro Red Car Line. DISCUSSION A 1990s study of the San Pedro waterfront envisioned significant development along the waterfront, from the Catalina and World Cruise Terminals on the north to Ports O’ Call Village and the 22nd St. / East Channel / West Channel / Los Angeles Harbor on the south. One of the components of this study was for a rail line to operate between the locations. In turn, the Port of Los Angeles (POLA) opened the 1.5 mile Waterfront Red Car Line on July 19, 2003 with four high platform stations serving the World Cruise Center, Downtown San Pedro, Ports O’ Call, and the Marina. Initial operation provided regular service Fridays thru Mondays, using two trolleys from 10am to 6pm and on days when cruise ships were in Port. In 2010, regular service was reduced to Fridays thru Sundays using one trolley car, operating from 12pm to 9pm with a $1 fare for the entire day and free during special events. Findings From 2005 through 2009, annual ridership was reported to have about 103,000 passengers on average. -

Archaeological Survey Report

F.2 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY REPORT CULTURAL RESOURCES SURVEY REPORT FOR THE SAN PEDRO WATERFRONT PROJECT LOCATED IN THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES LOS ANGELES COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: Los Angeles Harbor Department Environmental Management Division 425 South Palos Verdes Street San Pedro, California 90733 Prepared by: ICF Jones & Stokes 811 West 7th Street, Suite 800 Los Angeles, California 90017 213/627-5376 August 2008 Table of Contents SUMMARY OF FINDINGS ......................................................................................................... 1 I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 2 II. REGULATORY SETTING ................................................................................ 3 FEDERAL REGULATIONS ................................................................................ 3 STATE REGULATIONS ...................................................................................... 4 LOCAL REGULATIONS ..................................................................................... 6 III. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................. 7 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT .............................................................................. 7 PREHISTORIC CULTURAL SETTING .............................................................. 7 ETHNOGRAPHY ................................................................................................. 9 HISTORIC BACKGROUND ............................................................................. -

The Port of Los Angeles Waterfront Red Car Line Exciting Attractions Are Just a Stop Away!

The Waterfront Red Car Line Fare The Pacific Electric Railway was once America's One-Day Unlimited Ride Fare: $1.00 largest interurban railway system. The "Big Red Cars" Children 6 and under are free when accompanied by traversed the Los Angeles region on more than 1,000 an adult. miles of rail lines. The last Red Car was retired from service in 1961. Red Car ticket is transferable for FREE rides on the San Pedro Electric Trolleys and the Cruise Center Today, the Red Car heritage lives on in the Port of Los shuttle. (See map inside) Angeles Waterfront Red Car Line. Replica Cars 500 and 501 were constructed by Port of Los Angeles Hours of Operation craftsmen and patterned after an early 1900s Pacific Electric 500-class design. The exterior paint color and Days of Operation: Friday through Monday interior woodwork are exact replicas of the original 500 class cars that ran on the Pacific Electric from Hours: 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. 1903-1930 including routes to the San Pedro Station Service every 20 minutes at 5th Street and Harbor Boulevard. The Red Cars will also run on SELECT Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays when cruise ships are in the Port. Rules for Riding • Stay off the boarding ramp until the car is stopped in the station. • Have your $1.00 fare ready as you enter. Conductors carry no change. • Shoes and shirt are required. • Children under 12 must be accompanied by an adult. The Port of • Bicycles and roller skates are not allowed. -

LA Waterfront Land for Residential Development 54 Residential Units/Retail Or 98 Residential Units 319-327 N Harbor Blvd | San Pedro, CA 90731

LA Waterfront Land for Residential Development 54 Residential Units/Retail or 98 Residential Units 319-327 N Harbor Blvd | San Pedro, CA 90731 ➢ 24,205 SF Zoned C2-RD-CDO / Located in the Tier 2 TOC / 60% density bonus / over R4 density 98 residential units total ➢ Fully entitled for 54 multi-residential apartments over 1,470 square feet of commercial space with spectacular bridge to break water views ➢ Located in an Opportunity Zone - Tax Incentives & Preferential Tax Treatment ➢ Opportunity for investor/developer to build to in place entitlements or increased density ➢ Immediate area is undergoing major redevelopment along the waterfront | LA Waterfronts Project Website STEPHEN LAMPE OLGA WRIGHT RE/MAX COMMERCIAL & INVESTMENT REALTY Executive Vice President Senior Investment Associate 23001 Hawthorne Blvd, Suite 205 (310) 802-2501 (310) 802-2550 Torrance, CA 90505 [email protected] [email protected] (310) 802-2500 BRE #01164364 BRE #01315042 www.remaxcir.com Each office independently owned and operated LA WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT SITE 319-327 N Harbor Blvd | San Pedro, CA 90731 SITE SURVEY ADDRESS: 319 & 327 North Harbor Boulevard ASSESOR PARCEL NUMBER(S): 7449-014-013 & 7449-014-014 TOTAL LOT AREA: 24,205 Square Feet / Vacant TOPOGRAPHY: Flat corner lot with access from three sides, signalized intersection ZONING: [T] [Q] C2-2D-CDO T.O.C. (Transportation Oriented Corridor): Yes, Tier 2 ENTITLEMENTS: APPROVED FOR: 54 residential units & 1,470 square feet commercial ENTITLED BUILDING FOOTPRINT: As per setbacks ENTITLED BUIDLING ENVELOPE: 70,671 square feet ENTITLED HEIGHT: 69 feet from grade ENTITLED F.A.R.: 3 to 1 POTENTIAL DEVELOPMENT WITH T.O.C. -

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES.1 Introduction

ES 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 ES.1 Introduction 3 This draft environmental impact report (EIR) assesses impacts related to the 4 Wilmington Waterfront Development Project proposed by the Los Angeles Harbor 5 Department (LAHD). LAHD administers development within the Port of Los 6 Angeles (Port) and overall Port operations. The proposed Project is located in the 7 Port of Los Angeles Plan area and in the Wilmington-Harbor City Community Plan 8 area. The western portion of the proposed Project is adjacent to the community of 9 San Pedro in the City of Los Angeles. 10 This draft EIR fulfills the requirements of the California Environmental Quality Act 11 (CEQA) (California Public Resources Code [PRC] Section 21000 et seq.) and the 12 Guidelines for Implementation of the California Environmental Quality Act of 1970 13 (CEQA Guidelines) (14 California Code of Regulations [CCR] Section 15000 et 14 seq.). LAHD is the CEQA lead agency. 15 The draft EIR describes the environmental resources that would be affected by the 16 proposed Project and evaluates the significance of the potential impacts to those 17 resources as a result of constructing and operating the proposed Project. 18 ES.1.1 Project Boundary 19 The proposed Project site is generally bounded by Lagoon Avenue to the west, Broad 20 Avenue to the east, C Street to the north, and Slip 5 to the south, where over-water 21 viewing piers and floating docks are proposed. The site includes the Waterfront Red 22 Car Line and the multi-modal California Coastal Trail (CCT) linkages beginning in 23 the west at Swinford Street, moving along Front Street to John S. -

![Survey of Streetcar Cities] Summaries of the Various Streetcar Projects from Around the United States](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7631/survey-of-streetcar-cities-summaries-of-the-various-streetcar-projects-from-around-the-united-states-2967631.webp)

Survey of Streetcar Cities] Summaries of the Various Streetcar Projects from Around the United States

2012 [SURVEY OF STREETCAR CITIES] SUMMARIES OF THE VARIOUS STREETCAR PROJECTS FROM AROUND THE UNITED STATES Introduction Streetcars are enjoying a national revival in these early years of the 21st century. As communities across the nation rediscover the charm and efficiency of this short distance transit option, they are investing in new streetcar lines or extensions of existing operations. This survey in support of The Community Streetcar Coalition (CSC) was commissioned to track important streetcar development projects, planned or underway, in major U.S. cities. Portland Streetcar Inc. funded this work with the partial proceeds of its 2005 Rudy Bruner Gold Medal Award for Urban Excellence. This survey report is a living, working document. It will be updated regularly, and shared with policymakers, opinion leaders, interested municipalities, and those involved in streetcar issues and technologies. Cities wishing to be included in subsequent iterations of this document should contact Julie Gustafson, [email protected]. The Community Streetcar Coalition The Community Streetcar Coalition was established in 2004. It is comprised of cities, transit authorities and private sector that are focused on supporting the Small Starts program and establishment of a program that supports streetcars in the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU) and advocating with Federal Transit Administration (FTA) to implement the Small Starts program. The CSC conducts monthly phone calls for members and twice