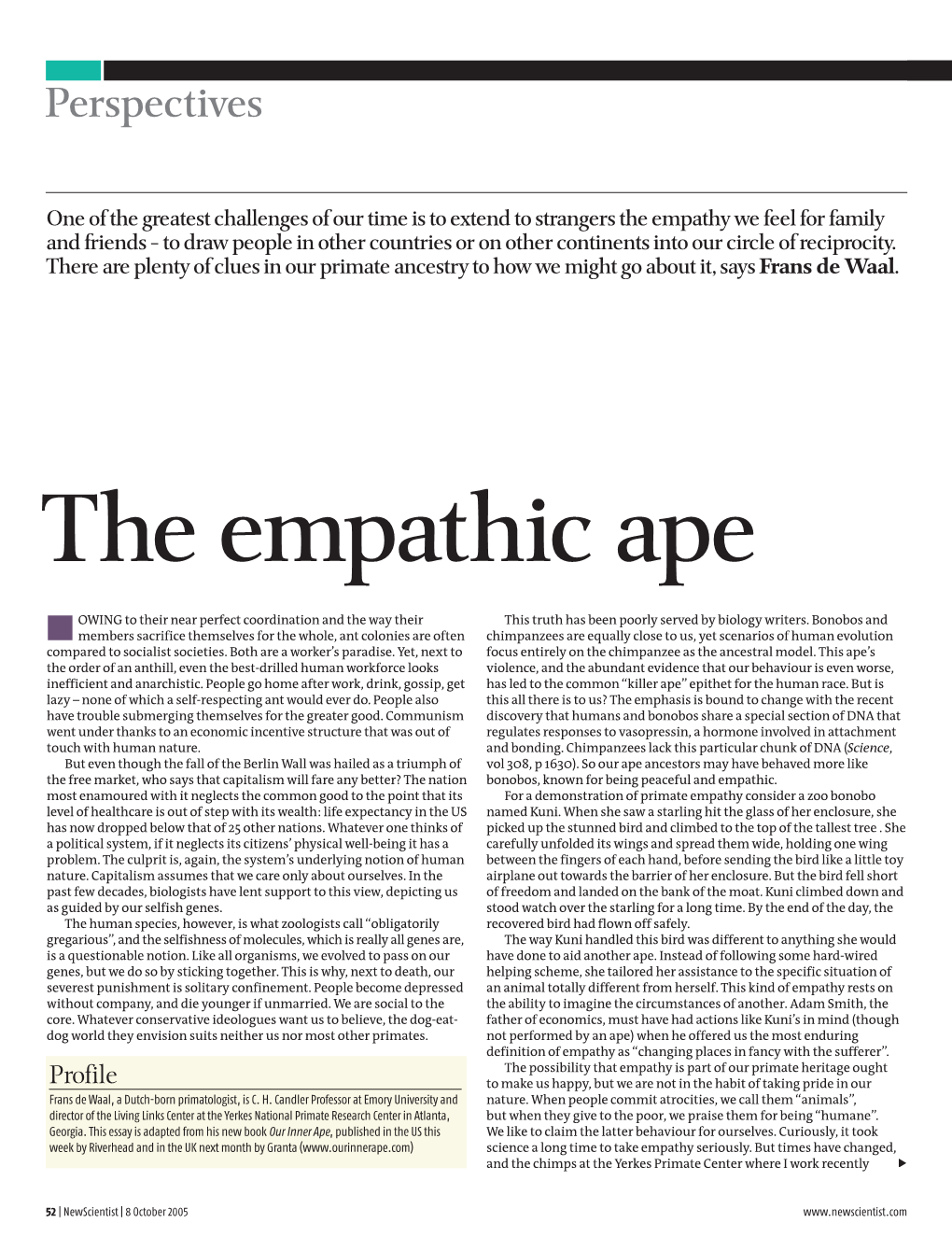

The Empathic Ape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021

More Fun Than Fun: The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021 An iconic photo of Konrad Lorenz with his favourite geese. Photo: Willamette Biology, CC BY-SA 2.0 This article is part of the ‘More Fun Than Fun‘ column by Prof Raghavendra Gadagkar. He will explore interesting research papers or books and, while placing them in context, make them accessible to a wide readership. RAGHAVENDRA GADAGKAR Among the books I read as a teenager, two completely changed my life. One was The Double Helix by Nobel laureate James D. Watson. This book was inspiring at many levels and instantly got me addicted to molecular biology. The other was King Solomon’s Ring by Konrad Lorenz, soon to be a Nobel laureate. The study of animal behaviour so charmingly and unforgettably described by Lorenz kindled in me an eternal love for the subject. The circumstances in which I read these two books are etched in my mind and may have partly contributed to my enthusiasm for them and their subjects. The Double Helix was first published in London in 1968 when I was a pre-university student (equivalent to 11th grade) at St Joseph’s college in Bangalore and was planning to apply for the prestigious National Science Talent Search Scholarship. By then, I had heard of the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA and its profound implications. I was also tickled that this momentous discovery was made in 1953, the year of my birth. I saw the announcement of Watson’s book on the notice board in the British Council Library, one of my frequent haunts. -

The Age of Empathy Is That Human Nature Offers a Dewa 9780307407764 5P 00 R1.Qxp 7/24/09 2:58 PM Page X

Age of Empathy 28/06/2011 10:16 Page 1 Age of Empathy 28/06/2011 10:16 Page 2 The Age of Empathy Copyright © 2009 by Frans de Waal This edition published by arrangement with Harmony Books, NATURE’S LESSONS an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division FOR A KINDER SOCIETY of Random House, Inc. First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Souvenir Press Ltd 43 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3PD This paperback edition first published in 2011 Reprinted 2012 The right of Frans de Waal to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Frans de Waal Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, With drawings by the author stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Copyright owner. ISBN 9780285640382 Design by Debbie Glasserman Souvenir Press This paperback published in 2019 First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Souvenir Press, an imprint of Profile Books Ltd 3 Holford Yard Bevin Way London WC1X 9HD www.profilebooks.com This edition published by arrangement with Harmony Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. Copyright © Frans de Waal, 2009, 2019 The right of Frans de Waal to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 All rights reserved. -

Korsgaard on De Waal

Morality and the Distinctiveness of Human Action Christine M. Korsgaard Harvard University What is different about the way we act that makes us, and not any other species, moral beings? - Frans de Waal1 A moral being is one who is capable of comparing his past and future actions or motives, and of approving or disapproving of them. We have no reason to suppose that any of the lower animals have this capacity. - Charles Darwin2 Two issues confront us. One concerns the truth or falsehood of what Frans de Waal calls “Veneer Theory.” This is the theory that morality is a thin veneer on an essentially amoral human nature. According to Veneer Theory, we are ruthlessly self-interested creatures, who conform to moral norms only to avoid punishment or disapproval, only when others are not watching us, or only when our commitment to these norms is not tested by strong temptation. The second concerns the question whether morality has its roots in our evolutionary past, or represents some sort of radical break with that past. De Waal proposes to address these two questions together, by adducing evidence that our closest relatives in the natural world exhibit tendencies that seem intimately related to morality – sympathy, empathy, sharing, conflict resolution, and so on. He concludes that the roots of 1 In Good-Natured: The Origins of Right and Wrong in Humans and Other Animals. Cambridge, USA: Harvard University Press, 1996, p. 111 2 In The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981, pp. 88-89. -

01De Waal Part I 1-80.Qxd

We approve and we disapprove because we cannot do otherwise. Can we help feeling pain when the fire burns us? Can we help sympathizing with our friends? —Edward Westermarck (1912 [1908]: 19) Why should our nastiness be the baggage of an apish past and our kindness uniquely human? Why should we not seek continuity with other animals for our “noble” traits as well? —Stephen Jay Gould (1980: 261) 0 omo homini lupus —“man is wolf to man”—is an ancient Roman proverb popularized by Thomas H Hobbes. Even though its basic tenet permeates large parts of law, economics, and political science, the proverb contains two major flaws. First, it fails to do justice to canids, which are among the most gregarious and cooperative ani mals on the planet (Schleidt and Shalter 2003). But even worse, the saying denies the inherently social nature of our own species. Social contract theory, and Western civilization with it, seems saturated with the assumption that we are asocial, even nasty creatures rather than the zoon politikon that Aristotle saw in us. Hobbes explicitly rejected the Aristotelian view by proposing that our ancestors started out autonomous and combative, establishing community life only when the cost of strife became unbearable. According to Hobbes, social life 4 FRANS DE WAAL never came naturally to us. He saw it as a step we took reluc tantly and “by covenant only, which is artificial” (Hobbes 1991 [1651]: 120). More recently, Rawls (1972) proposed a milder version of the same view, adding that humanity’s move toward sociality hinged on conditions of fairness, that is, the prospect of mutually advantageous cooperation among equals. -

Frans De Waal and Pragmatist Naturalism

Contemporary Pragmatism Editions Rodopi Vol. 10, No. 1 (June 2013), 29–59 ©2013 What Piece of Work is Man? Frans de Waal and Pragmatist Naturalism Wouter de Been and Sanne Taekema Frans de Waal has questioned the liberal notion that humans are primarily defined by selfishness. De Waal claims that primates are gregarious and guided by empathy. Hence, he argues we should return to Adam Smith’s focus on empathy. We believe a return to pragmatism would be more appropriate. Pragmatism largely conforms to the view of human nature that De Waal’s research now supports and can provide a more sophisticated framework to integrate recent insights about primate sociality into political and legal theory. The intelligent acknowledgment of the continuity of nature, man and society will alone secure a growth of morals which will be serious without being fanatical, aspiring without sentimentality, adapted to reality without conventionality, sensible without taking the form of calculation of profits, idealistic without being romantic. – John Dewey, 1922 (1983, 13) 1. Introduction At the core of much present-day, liberal, legal and political theory there is a notion of human nature defined in terms of individualism, rationality and self- interest.1 This definition is central to most forms of contract theory. People are assumed to be calculating and self-regarding loners, reluctant to join the bonds of social union. An autonomous individual can only be asked to suffer the burdens of community, many legal and political theorists suggest, if certain preconditions are met and individual freedoms are guaranteed. Primatologist Frans de Waal has become increasingly vocal in his criticism of these presuppositions of modern liberal thought and the bleak view of human nature implicit in them. -

Neural Substrates of Decision-Making in Economic Games

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Neural Substrates of Decision-Making in Economic Games Stanton, Angela A. Claremont Graduate University 12 May 2007 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/4030/ MPRA Paper No. 4030, posted 13 Jul 2007 UTC Volume 1, Issue 1, 2007 Neural Substrates of Decision-Making in Economic Games Angela A. Stanton, Assistant Professor of Economics, Argyros School of Business & Economics, Chapman University, California. Email: [email protected] Abstract In economic experiments decisions often differ from game-theoretic predictions. Why are people generous in one-shot ultimatum games with strangers? Is there a benefit to generosity toward strangers? Research on the neural substrates of decisions suggests that some choices are hormone-dependent. By artificially stimulating subjects with neuroactive hormones, we can identify which hormones and brain regions participate in decision- making, to what degree and in what direction. Can a hormone make a person generous while another stingy? In this paper, two laboratory experiments are described using the hormones oxytocin (OT) and arginine vasopressin (AVP). Concentrations of these hormones in the brain continuously change in response to external stimuli. OT enhances trust (Michael Kosfeld et al. 2005b), reduce fear from strangers (C. Sue Carter 1998), and has anti-anxiety effects (Kerstin Uvnäs-Moberg, Maria Peterson 2005). AVP enhances attachment and bonding with kin in monogamous male mammals (Jennifer N. Ferguson et al. 2002) and increases reactive aggression (C. Sue Carter 2007). Dysfunctions of OT and/or AVP reception have been associated with autism (Miranda M. Lim et al. 2005). In Chapter One I review past experiments with the ultimatum (UG) and dictator (DG) games and visit some of the major results in the literature. -

Frans B. M. De Waal Joint Ventures Require Joint Payoffs: Fairness Among Primates

Frans B. M. de Waal Joint Ventures Require Joint Payoffs: Fairness among Primates wall street is sometimes compared to a darwinian jungle. Nice guys finish last, it is said, and only the strong survive. This is an adequate enough description, but not entirely true, neither for the stock market nor for life in the jungle. When Richard Grasso, head of the New York Stock Exchange, revealed a pay package for himself of close to $200 million, there was public outcry. As it happened, on the very same day that Grasso was forced to resign, my team published a study on monkey fairness. Commentators could not resist contrast- ing Grasso with capuchin monkeys, suggesting he could have learned a thing or two from them (Surowiecki, 2003). Obviously, in a social system built on individual strength, the strong have an advantage. But as soon as the system introduces addi- tional factors relevant for survival, the picture changes. The present topic of fairness deals with the influence of cooperation: obviously there would be no need to worry about fairness if everyone acted inde- pendently. Cooperation is widespread in the animal kingdom. Even the simple act of living together represents cooperation. In the absence of predators or enemies, animals do not need to stick together, and they would in fact be better off living alone. The first reason for group life is security. On top of this, many animals actively pursue common goals. By working together they attain benefits they could not attain alone. This social research Vol 73 : No 2 : Summer 2006 349 means that each individual needs to monitor the division of spoils. -

Primates, Monks and the Mind the Case of Empathy

Frans de Waal and Evan Thompson Interviewed by Jim Proctor Primates, Monks and the Mind The Case of Empathy Jim Proctor: It’s Monday, February 14th, Valentine’s Day, 2005. I’m pleased to welcome Evan Thompson and Frans de Waal, who have joined us as distin- guished guest scholars for a series of events in connection with a program spon- sored by UC Santa Barbara titled New Visions of Nature, Science, and Religion.1 The theme of their visit is ‘Primates, Monks, and the Mind’. What we’re going to discuss this morning — empathy — is quite appropriate to Valentine’s Day, and is one of many ways to bring primates, monks, and the mind together. I know that empathy has been important to both of you in your research. So we will explore possible overlap in the ways that someone inter- ested in the relationship between phenomenology and neuroscience — or ‘neurophenomenology’ — and someone with a background in cognitive ethol- ogy come at the question of empathy. I’d like to start by making sure we frame empathy in a common way. What would you say are the defining features of this capacity we’re calling empathy? Frans De Waal: At a very basic level, it is connecting with others, both emo- tionally and behaviourally. So, if you show a gesture or a facial expression, I may actually mimic it. There’s evidence that people unconsciously mimic the facial expression of others, so that when you smile, I smile (Dimberg et al., 2000). At the higher levels, of course, it is more of an emotional connection — I am affected by your emotions; if you’re sad, that gives me some sadness. -

Monkeys, Men, and Moral Responsibility: a Neo-Aristotelian

Monkeys, Men, and Moral Responsibility: A Neo-Aristotelian Case for a Qualitative Distinction Paul Carron, Baylor University Forthcoming in Southwestern Philosophical Review 33 (1) I. Introduction On February 17, 2009, a large chimp named Travis attacked a friend of his owner, blinding her, severing her nose, ears, hands, and severely lacerating her face. The police subsequently shot and killed Travis. The Primatologist Frans de Waal wrote about the incident on several occasions, bemoaning the state of the laws that allow humans to own chimps as pets.1 But one thing was curiously absent from de Waal’s comments: he never blamed Travis for his actions. Surely if Travis were a mentally competent human male there would be no doubt about who to blame – we would blame Travis. But no one – including one of the foremost advocates of continuity between primate behavior and human morality – blames a chimp for a brutal murder. Initially this doesn't surprise us. After all, we don’t hold very young children morally responsible for their actions in the same way that we hold adults accountable. Furthermore, many of us accept that non-human primates do not have the cognitive and psychological faculties necessary for responsibility ascriptions. Humans can deliberate and weigh reasons about whether or not to harm another person or animal, and can form an intention based on that deliberation and act on that intention; primates and other non-human animals are not privy to the same complex mental processes. But de Waal has spent his career arguing for continuity between primate behavior and human morality. -

Animal Consciousness: Paradigm Change in the Life Sciences

Animal Consciousness: Paradigm Change in the Life Sciences Martin Schönfeld University of South Florida This paper is a review of the breakthroughs in the empirical study of ani- mals. Over the past ªve years, a change in basic assumptions about ani- mals and their inner lives has occurred. (For a recent illustration of this paradigm change in the news, see van Schaik 2006.) Old-school scientists proceeded by and large as if animals were merely highly complex ma- chines. Behaviorism was admired for its consistently rigorous methodol- ogy, mirroring classical physics in its focus on quantiªable observation. In the old analytic climate, claims that animals are sentient raised method- ological and ideological problems and seemed debatable at best. Bolder claims, that animals are intelligent, or even self-aware in a way that is for all practical purposes human, were regarded as unfounded. Empirical trials to substantiate such claims were nipped in the bud, since it appeared that such inquiries would unduly humanize nonhuman beings. Scientists are not supposed to project their own intuitions, feelings, or thoughts on ob- jects of their investigation. Studying the afªnities of humans and animals would appear to violate this well-established rule, and would risk sliding down the slippery slope from fawns to Bambi, from rabbits to Thumper, and from science to myth. The task of science in the past four centuries had been to demythologize the past. Erasing myths had been the hallmark of progress; it turned astrology into astronomy, alchemy into -

Among Apes 1982) and Jane Goodall (In the Shadow of Man, 1971; the Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior, 1986) Are Examined in a Postmodern Perspective

31 AN INVESTIGATION OF THE HERMENEUTIC PROPERTIES OF WRITING PRIMATOLOGY Amy Todd ABSTRACT: The works of Frans de Waal (Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex Among Apes 1982) and Jane Goodall (In the Shadow of Man, 1971; The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior, 1986) are examined in a postmodern perspective. Ethnographers and primatologists traditionally leave the comfort of familiar surroundings to engage in a relatively long-term observa- tional, interactive and interpretive experience with the members of another society or the members of another species. The writing strategies of these two "chimpographers", as well as the ways in which these strategies influence the presentation of the authors' interpretations of their fieldwork experiences are examined for their hermeneutic qualities. An investigation of the hermeneutic properties of interpretation allows one to critically read an ethnography (or primatological work) and remain sensitive to its possible underlying political, historical, economic, racial and gender related motivations or determinants (Clifford 1986:6; Haraway 1989:8). Introduction The more [we] learn about these great apes, the deeper our identity crisis seems to become...If we look straight and deep into a chimpanzee's eyes, an intelligent, self-assured personality looks back at us.If they are animals, what must we be? (Franz de Waal 1982:18). It has come to me, quite recently, that it is only through a real understanding of the ways in which chimpanzees and man share similarities in behavior that we can reflect with meaning on the ways in which men and chimpanzees differ. And only then can we really begin to appreciate, in a biological and spiritual manner, the full extent of man's uniqueness (Jane Goodall 1971:251). -

Chapter 2 of Cetaceans and Ships; Or, the Moorings of Our Being

Chapter 2 Of Cetaceans and Ships; or, The Moorings of Our Being “L’imagination . se lassera plutôt de concevoir que la nature de fournir.” (Te imagination runs dry sooner than nature does.) —Pascal, Pensées Is the Sea a Medium? To understand media, we should start not on land but at sea. Te sea has long seemed the place par excellence where history ends and the wild be- gins: the abyss, a vast deep and dark mystery, unrecorded, unknown, un- mapped. Melville called the sea “Inviolate Nature primeval.” It has long been a profoundly unnatural environment for humans in both life and in thought. Seventy- one percent of the earth’s surface has been a sub- lime, uncanny place without limits and beyond understanding, the ulti- mate wasteland. Te ocean was once roiling with dragons, Leviathans, and pirates— a merciless mix of fate, wind, and weather that imperiled anyone brave or foolish enough to risk their life on ship. It is still a very dangerous place, a kind of planetary waste dump and graveyard for many forms of life, including hapless immigrants. Only recently have humans dipped much below its surface, with depth exploration historically having been limited to the shoreline. Both Babylonian and Hebrew ori- gin myths describe creation as the conquest of chaotic uncreated waters (tiamat, tehom). Te Book of Revelation, at the opposite end of the Bible from Genesis, seals this conquest by announcing a new heaven and earth 53 54 CHAPTER TWO in which the sea is no more, abolished as if in a fnal act of spite (Revela- tions 21:1).