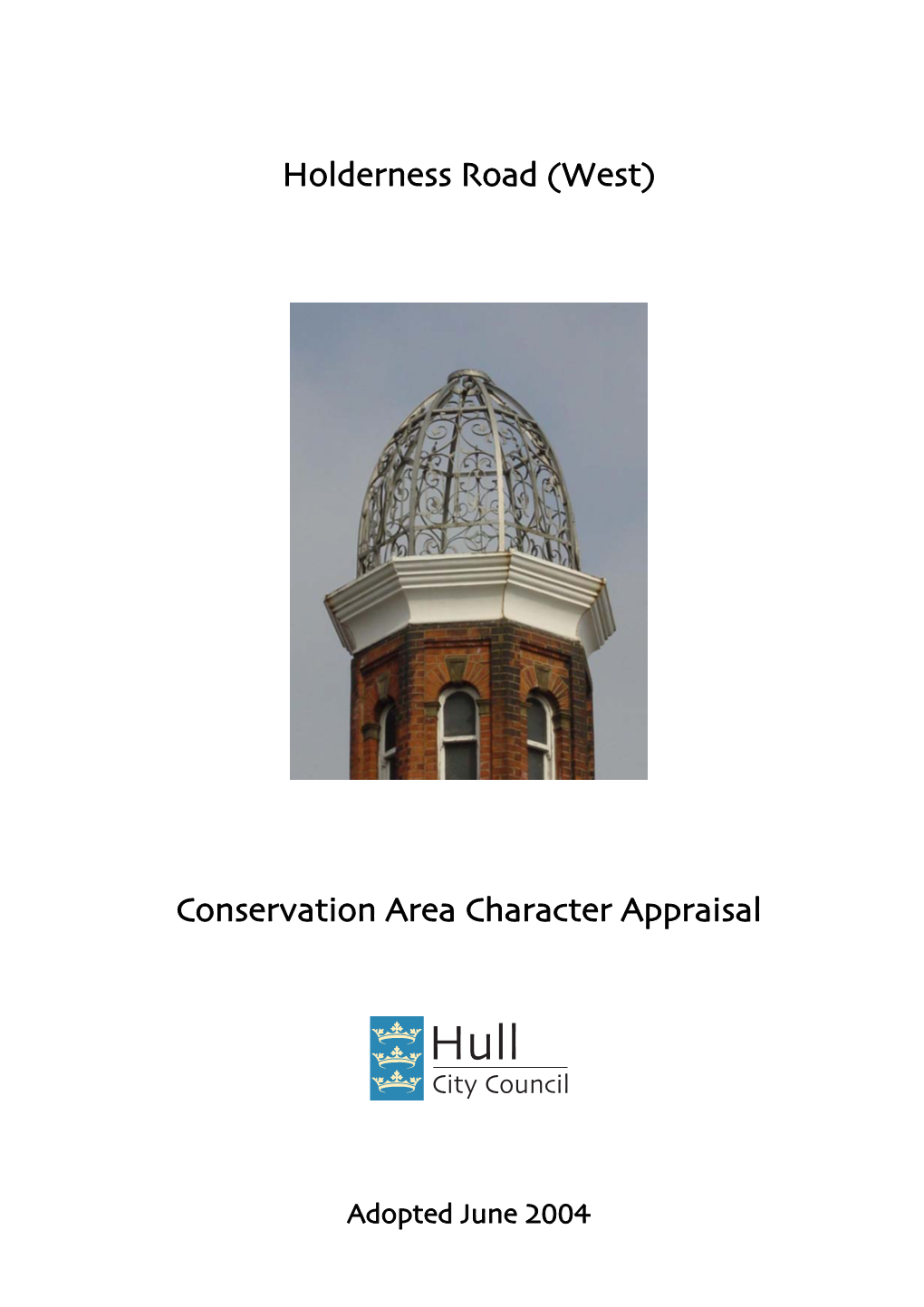

Holderness Road West Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Bus Services in the East Riding (Revised Following Public Consultation)

East Riding of Yorkshire Council Review of Bus Services in the East Riding (Revised following Public Consultation) December 2016 1 Review of Bus Services in the East Riding 2016 (Revised following Public Consultation) Table of Contents Page SECTION 1 The Review of Bus Services in the East Riding 2016: Background and Context. 5 SECTION 2 The Public Consultation on our proposals in the Review of Bus Services in the 7 East Riding 2016: Results and Analysis. SECTION 3 Summary by contract of our conclusions following analysis of the results of the 12 public consultation SECTION 4 Our Finalised Proposal for the future of supported bus services in the East 16 Riding and individual Bus Timetables for services which would be affected. 3 4 Section 1 The Review of Bus Services in the East Riding 2016: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 1.1 Following a comprehensive Parish Transport Needs Assessment journeys. We stated our intention to seek to develop alternative process the council developed a proposal for the future of mitigating transport options for the loss of these 59 contracts. supported bus services in the East Riding of Yorkshire. This These potential mitigation measures included either existing or proposal was subject to a full public consultation which ran proposed demand responsive transport options, or the possibility for 8 weeks from 27 June 2016 to 28 August 2016. We have of travelling on a different bus or at a different time. given due regard to what residents have told us through the consultation process, and have revised our original proposal to 1.7 We consulted on this proposal, through advertising a survey ensure that we can maintain a public and community transport online at: www.eastriding.gov.uk/haveyoursay network that meets people’s strategic transport needs. -

View in Website Mode

8 bus time schedule & line map 8 Hull Interchange, Hull View In Website Mode The 8 bus line (Hull Interchange, Hull) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Hull Interchange, Hull: 7:32 AM - 8:10 PM (2) Hull Interchange, Hull: 6:00 AM - 7:40 PM (3) North Point Shopping Centre, Bransholme - Hull Interchange, Hull: 5:53 AM - 6:23 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 8 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 8 bus arriving. Direction: Hull Interchange, Hull 8 bus Time Schedule 80 stops Hull Interchange, Hull Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:55 AM - 5:55 PM Monday 7:32 AM - 8:10 PM Hull Interchange, Hull Margaret Moxon Way, Kingston Upon Hull Tuesday 7:32 AM - 8:10 PM Trafalgar Street, Sculcoates Wednesday 7:32 AM - 8:10 PM Leonard Street, Sculcoates Thursday 7:32 AM - 8:10 PM Friday 7:32 AM - 8:10 PM Wellington Lane, Sculcoates Saturday 9:02 AM - 8:10 PM Endeavour School, Sculcoates Cave Street, Sculcoates Grove Street, Sculcoates 8 bus Info 250 Beverley Road, Kingston Upon Hull Direction: Hull Interchange, Hull Stops: 80 Pearson Avenue, Sculcoates Trip Duration: 68 min Line Summary: Hull Interchange, Hull, Trafalgar Lambert Street, Newland Street, Sculcoates, Leonard Street, Sculcoates, Wellington Lane, Sculcoates, Endeavour School, Washington Street, Newland Sculcoates, Cave Street, Sculcoates, Grove Street, Sculcoates, Pearson Avenue, Sculcoates, Lambert Street, Newland, Washington Street, Newland, Ash Ash Grove, Newland Grove, Newland, Haworth Street, Newland, Desmond Avenue, Newland, -

Wilberforce Court

WILBERFORCE COURT ALFRED GELDER STREET • HULL • HU1 1NE OVERVIEW 04 - 05 THE VISION 06 - 07 THE LIFESTYLE 08 - 11 EASILY ACCESSIBLE 12 - 13 KINGSTON UPON HULL 14 - 17 DISTINGUISHED THE PROPERTY 18 - 23 THE INTERIORS 24 - 33 LIVING IN THE FINISHES 34 - 37 OUTSTANDING IDEALLY CONNECTED 38 - 39 OWNERSHIP MADE EASIER 40 - 41 SURROUNDINGS FLEXIBLE OWNERSHIP 42 - 43 THE DEVELOPER 44 - 45 SUMMARY 46 - 47 WILBERFORCE COURT 04 05 The result of a visionary £14 million redevelopment project, Wilberforce Court is set to produce some of the most desirable residential units in Hull’s city centre. Originally built as high-end offices, the building is now witnessing an OVERVIEW internal transformation. The work, which will be completed in two phases with the first phase completing Q1 2023, will create light, beautifully equipped apartments over four levels, all built over secure on-site parking. Standing at the eastern side of the city centre, immediately adjacent to the historic ‘Old Town’ museum quarter, this is a property that boasts character, convenience and exceptional quality. AT A GLANCE A lavish multimillion pound redevelopment Attractive pre-market prices Phase one comprises of a mix of 112 studio, single-bedroom and two-bedroom units CHARACTER, An outstanding specification CONVENIENCE AND EXCEPTIONAL Secure, light and energy efficient QUALITY Exceptionally convenient city-centre location Phase one completion Q1 2023 ELEGANT LIVING 06 07 THE VISION Featuring four residential storeys rising above private undercroft parking, Wilberforce Court offers a rare combination of convenience, modernity and seclusion. The private residents’ courtyard affords an area for quiet retreat, yet the property itself is situated close to all the amenities of the city centre. -

Hull Labour Group Responds to This Further Consultation Wholly Bemused by This Unusual Irregular Process

THE HULL CITY COUNCIL LABOUR GROUP SUBMISSION TO THE FURTHER DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HULL CITY COUNCIL WARDS TH 8 AUGUST 2017 1 Contents Page Preface & Introduction 3 East Hull Wards 6 Sutton, Ings, Longhill & Bilton Grange, Marfleet and 6 Southcoates Drypool and Holderness 8 North Hull Wards 22 Avenue Ward 22 Kingswood, West Carr, North Carr Wards 25 Beverley Sculcoates Ward 33 Central Ward 54 Orchard Park, University Wards 58 Wyke Ward 59 West Hull Wards 60 Pickering 60 Newington & Gipsyville 63 St. Andrew’s & Docklands 72 Derringham 79 Boothferry 80 Concluding Statement 81 Appendices – scans of surveys sent separately due to volume. 2 Preface The Hull Labour Group responds to this further consultation wholly bemused by this unusual irregular process. Our unhappiness stems from the fact that we believe we were fundamentally misled by Commission staff who unequivocally stated that the first set of draft recommendations from the LGBCE would be based on a three- member Ward settlement. This LGBCE advice was given at the Labour Group Briefing with Officers and Members (including a Conservative Councillor) present). This then informed our initial response in October 2016. The alleged rationale and premature dismissal of a three-member Warding Settlement as proposed by Labour, seems to stem from the LGBCE’s refusal to consider a cross-river Ward. It is regrettable that the LGBCE continually refers to “’…our decision in relation to the River Hull…” [LGBCE Page 21 Paragraph 85, June 2017]. At this stage the LGBCE should have ONLY been dealing with recommendations, but it is clear, despite a lack of strong evidence, the LGBCE had made their mind up, preferring the repetition against such a ward by one political party. -

933 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

933 bus time schedule & line map 933 Burstwick - Wyke College View In Website Mode The 933 bus line (Burstwick - Wyke College) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bricknell Estate <-> Burstwick: 4:15 PM (2) Burstwick <-> Bricknell Estate: 7:20 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 933 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 933 bus arriving. Direction: Bricknell Estate <-> Burstwick 933 bus Time Schedule 57 stops Bricknell Estate <-> Burstwick Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 4:15 PM Bishop Alcock Road, Bricknell Estate Tuesday 4:15 PM Leyburn Avenue, Bricknell Estate Wednesday 4:15 PM Welton Grove, Bricknell Estate Thursday 4:15 PM Arram Grove, Inglemire Friday 4:15 PM Endyke Lane, Inglemire Saturday Not Operational Lastingham Close, Orchard Park 32nd Avenue, Orchard Park 933 bus Info 22nd Avenue, Orchard Park Direction: Bricknell Estate <-> Burstwick Stops: 57 Trip Duration: 71 min Greenwood Ave Library, Orchard Park Line Summary: Bishop Alcock Road, Bricknell Estate, Ada Holmes Circle, Kingston Upon Hull Leyburn Avenue, Bricknell Estate, Welton Grove, Bricknell Estate, Arram Grove, Inglemire, Endyke 6th Avenue, Orchard Park Lane, Inglemire, Lastingham Close, Orchard Park, 32nd Avenue, Orchard Park, 22nd Avenue, Orchard 2nd Avenue, Orchard Park Park, Greenwood Ave Library, Orchard Park, 6th Avenue, Orchard Park, 2nd Avenue, Orchard Park, Beverley Road, Ghost Estate Beverley Road, Ghost Estate, Elston Close, Ghost Estate, Ennerdale Leisure Centre, Sutton Park, -

677 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

677 bus time schedule & line map 677 Hull Interchange - Preston Cranswick Foods View In Website Mode The 677 bus line (Hull Interchange - Preston Cranswick Foods) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Hull Interchange, Hull - Preston Main Road, Preston: 5:00 AM - 5:30 AM (2) Preston Main Road, Preston - Hull Interchange, Hull: 5:50 AM - 6:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 677 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 677 bus arriving. Direction: Hull Interchange, Hull - Preston Main 677 bus Time Schedule Road, Preston Hull Interchange, Hull - Preston Main Road, Preston 41 stops Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:00 AM - 5:30 AM Hull Interchange, Hull Tuesday 5:00 AM - 5:30 AM Trafalgar Street, Sculcoates Wednesday 5:00 AM - 5:30 AM Leonard Street, Sculcoates Thursday 5:00 AM - 5:30 AM Wellington Lane, Sculcoates Friday 5:00 AM - 5:30 AM Endeavour School, Sculcoates Saturday Not Operational Cave Street, Sculcoates Grove Street, Sculcoates 677 bus Info 250 Beverley Road, Kingston Upon Hull Direction: Hull Interchange, Hull - Preston Main Pearson Avenue, Sculcoates Road, Preston Stops: 41 Trip Duration: 40 min Lambert Street, Newland Line Summary: Hull Interchange, Hull, Trafalgar Street, Sculcoates, Leonard Street, Sculcoates, Washington Street, Newland Wellington Lane, Sculcoates, Endeavour School, Sculcoates, Cave Street, Sculcoates, Grove Street, Ash Grove, Newland Sculcoates, Pearson Avenue, Sculcoates, Lambert Street, Newland, Washington Street, Newland, -

4 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

4 bus time schedule & line map 4 Greatƒeld - Orchard Park View In Website Mode The 4 bus line (Greatƒeld - Orchard Park) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bilton Grange: 5:50 AM - 7:30 PM (2) Hull: 10:37 PM (3) Hull: 6:18 PM - 8:26 PM (4) North Hull Estate: 6:46 AM - 10:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 4 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 4 bus arriving. Direction: Bilton Grange 4 bus Time Schedule 68 stops Bilton Grange Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:07 AM - 6:07 PM Monday 5:50 AM - 7:30 PM Orchard Park Tesco, North Hull Estate Tuesday 5:50 AM - 7:30 PM Sirius North Academy, North Hull Estate Wednesday 5:50 AM - 7:30 PM Thorpepark Academy, North Hull Estate Thursday 5:50 AM - 7:30 PM 8th Avenue, Kingston Upon Hull Friday 5:50 AM - 7:30 PM Pint & Pot, North Hull Estate Saturday 5:50 AM - 7:30 PM Dringshaw, North Hull Estate Rampant Horse, North Hull Estate Ainshaw, North Hull Estate 4 bus Info Bardshaw, Kingston Upon Hull Direction: Bilton Grange Stops: 68 Cladshaw, North Hull Estate Trip Duration: 55 min Line Summary: Orchard Park Tesco, North Hull Catherine Ellis House, North Hull Estate Estate, Sirius North Academy, North Hull Estate, Thorpepark Academy, North Hull Estate, Pint & Pot, 24th Avenue, North Hull Estate North Hull Estate, Dringshaw, North Hull Estate, Rampant Horse, North Hull Estate, Ainshaw, North Hull Estate, Cladshaw, North Hull Estate, Catherine 14th Avenue, Orchard Park Ellis House, North Hull Estate, 24th Avenue, North Hull Estate, 14th Avenue, -

Hull Times Index 1857-66

Table of Contents Agriculture ........................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Antiquities ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Army .................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Art ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Associations ......................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Banks & Finance ................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Books ................................................................................................................................................................................. 12 Bridges ............................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Buildings ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

East Area Committee

Please ask for: Jordan Scott Telephone: 01482 613026 Fax: 01482 614804 Email: [email protected] Text phone: 01482 300349 Date: Wednesday, 28 June 2017 Dear Councillor, East Area Committee The next meeting of the East Area Committee will be held at 09:30 on Thursday, 06 July 2017 in Kingston Wesley Church . The Agenda for the meeting is attached and reports are enclosed where relevant. Please Note: It is likely that the public, (including the Press) will be excluded from the meeting during discussions of exempt items since they involve the possible disclosure of exempt information as describe in Schedule 12A of the Local Government Act 1972. Yours faithfully, Democratic Services Officer for the Chief Executive Town Clerk Services, Hull City Council, The Guildhall, AlfredPage Gelder1 of 110 Street, Hull, HU1 2AA www.hullcc.gov.uk Tel: 01482 300300 East Area Committee To: Membership: Councillors Black, Clarkson, Craker, Gardiner, Hewitt, Keal, Thompson D, Thompson M and Turner Officers: Mark McEgan, Assistant City Manager (Housing Management) Alastair Shaw Community Manager (Neighbourhood Housing) Jordan Scott, Assistant Democratic Services Officer (x5) Public Sets: Reference Library Page 2 of 110 East Area Committee 09:30 on Thursday, 06 July 2017 Kingston Wesley Church A G E N D A PROCEDURAL ITEMS 1 Apologies To receive apologies for those Members who are unable to attend the meeting. 2 Declarations of Interest To remind Members of the need to record the existence and nature of any Personal and Discloseable Pecuniary interest in items on the agenda, in accordance with the Member Code of Conduct. -

81 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

81 bus time schedule & line map 81 Beverley View In Website Mode The 81 bus line (Beverley) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Beverley: 4:20 PM (2) Sutton Ings: 7:40 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 81 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 81 bus arriving. Direction: Beverley 81 bus Time Schedule 46 stops Beverley Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 4:20 PM Wilberforce College, Sutton Ings Tuesday 4:20 PM Camberwell Close, Sutton Ings Wednesday 4:20 PM St Bartholomew's Way, Sutton Ings Thursday 4:20 PM Pinderƒeld Close, Kingston Upon Hull Friday 2:50 PM Battersea Close, Sutton Ings Saturday Not Operational Elgin House, Sutton Ings Lanyon Close, Bransholme Mullion Close, Sutton-On-Hull 81 bus Info Mullion Close, Kingston Upon Hull Direction: Beverley Stops: 46 Sutton Close, Bransholme Trip Duration: 45 min Madron Close, Kingston Upon Hull Line Summary: Wilberforce College, Sutton Ings, Camberwell Close, Sutton Ings, St Bartholomew's Swinderby Garth, Bransholme Way, Sutton Ings, Battersea Close, Sutton Ings, Elgin Swinderby Garth, Kingston Upon Hull House, Sutton Ings, Lanyon Close, Bransholme, Mullion Close, Sutton-On-Hull, Sutton Close, Porlock Drive, Bransholme Bransholme, Swinderby Garth, Bransholme, Porlock Drive, Bransholme, Haydock Garth, Bransholme, Haydock Garth, Bransholme Foredyke Bridge, North Bransholme, Sedgebrook Grove, Kingswood, Emberton Park, Kingswood, Foredyke Bridge, North Bransholme Parnham Drive, Kingswood, Salcey Close, Kingswood, -

C DSLC Records of the Leonard Chamberlain Trust 1699-2006

Hull History Centre: Records of the Leonard Chamberlain Trust C DSLC Records of the Leonard Chamberlain Trust 1699-2006 Accession Numbers: 96/282 and 13/69 Historical Background: Leonard Chamberlain (1642-1716) was a woollen draper, and had a business in the Market Place in Hull but lived in Selby. For many years he was a dissenting Presbyterian but would eventually become a Unitarian. By will of 1716 Chamberlain devised various properties in Hull, Selby, Hessle and Sutton and Stoneferry to provide weekly pensions to poor people of Hull and Sutton and Stoneferry. Eventually the Trust would use this provision to endow almshouses in Sutton and Selby. In addition, there were some educational and religious provisions included in Chamberlain's will. These covered the same geographical areas as well as parts of the East Riding. It would provide, for example, schoolmasters and funds for the Bowlalley Lane Chapel. These provisions would later be modernised to include, for instance, support for young people in education. The Trust continues today, and covers the same aspects as Leonard Chamberlain identified in his original will. Custodial History: The first deposit was in 1996 by the then secreary of the trust, Mrs Caley. The second deposit, the collection of deeds for properties owned by the Trust, was by Alison Nicholson in 2013. Description: Minutes, orders, payment books, accounts and balances, building plans and deeds Arrangement: C DSLC/1 Administrative records 1719 -1981 C DSLC/2 Deeds of properties owned by the Trust 1699-2006 Extent: 3 boxes 65 items, 3 volumes Related material: A history of the charity entitled 'The History of the Leonard Chamberlain Trust' by Bryan Burgess can be located at L.362.5. -

Sutton-In-Holderness. the Manor, the Berewic, and the Village Community

/SM. SUTTON-IN-HOLDERNESS. SUTTON-IN-HOLDERNESS THE MANOR, THE BEREWIC, AND THE VILLAGE COMMUNITY. BY THOMAS BLASHILL, F.R.I. B.A., The Superintending Architect of Metropolifan Buildings. SEAL OF SIR THOMAS DE SUTTON. HULL : WILLIAM ANDREWS & CO. AND A. BROWN & SONS, LTD. AND AT 5, FARRINGDON AVENUE, LONDON, E.G. I«96. SATHEF PREFACE. Domesday record of the Manor and the THEBerewic which, at the time of the Conquest, were intermixed under the name of Sudtone, describes a tract of land containing no more than a fifth of the area of mediaeval and modern Sutton. It is in the earlier chapters of the Chronica Monasterii cie Melsa, which deal with the twelfth century, that we first recognise the broad meadows and far-stretching pastures out of the midst of which there rose, on a group of gently swelling hills, the carucates and oxgangs of the more ancient town. But since the days of our great-grandfathers, both the older and the newer lands have been seen in a changed aspect, under the network of hedges, tree-bedecked, which, since 1767, has covered the old meadows and pastures and the open arable fields. Long ago I formed the idea of making more familiarly known the condition of the parish at two or three of the most notable periods of its history. In 1892, impressed with the accuracy and the interest of the monastic Chronicle, I read before the British " Archaeological Association a paper on Sutton-in- Holderness and the Monks of Meaux."* In the Transactions of the East Riding Anticjuarian Society, * Pron.