Language Contact in Gibraltar English: a Pilot Study with ICE-GBR*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hearing on the Report of the Chief Justice of Gibraltar

[2009] UKPC 43 Privy Council No 0016 of 2009 HEARING ON THE REPORT OF THE CHIEF JUSTICE OF GIBRALTAR REFERRAL UNDER SECTION 4 OF THE JUDICIAL COMMITTEE ACT 1833 before Lord Phillips Lord Hope Lord Rodger Lady Hale Lord Brown Lord Judge Lord Clarke ADVICE DELIVERED ON 12 November 2009 Heard on 15,16, 17, and 18 June 2009 Chief Justice of Gibraltar Governor of Gibraltar Michael Beloff QC Timothy Otty QC Paul Stanley (Instructed by Clifford (Instructed by Charles Chance LLP) Gomez & Co and Carter Ruck) Government of Gibraltar James Eadie QC (Instructed by R J M Garcia) LORD PHILLIPS : 1. The task of the Committee is to advise Her Majesty whether The Hon. Mr Justice Schofield, Chief Justice of Gibraltar, should be removed from office by reason of inability to discharge the functions of his office or for misbehaviour. The independence of the judiciary requires that a judge should never be removed without good cause and that the question of removal be determined by an appropriate independent and impartial tribunal. This principle applies with particular force where the judge in question is a Chief Justice. In this case the latter requirement has been abundantly satisfied both by the composition of the Tribunal that conducted the initial enquiry into the relevant facts and by the composition of this Committee. This is the advice of the majority of the Committee, namely, Lord Phillips, Lord Brown, Lord Judge and Lord Clarke. Security of tenure of judicial office under the Constitution 2. Gibraltar has two senior judges, the Chief Justice and a second Puisne Judge. -

The Book of Abstract

JADH 2018 “Leveraging Open Data” September 9-11, 2018 Hitotsubashi Hall, Tokyo https://conf2018.jadh.org Proceedings of the 8th Conference of Japanese Association for Digital Humanities Co-hosted by: Center for Open Data in the Humanities, Joint Support-Center for Data Science Research, Research Organization of Information and Systems Hosted by: JADH2018 Organizing Committee under the auspices of the Japanese Association for Digital Humanities TEI 2018 “TEI as a Global Language” September 9-13, 2018 Hitotsubashi Hall, Tokyo https://tei2018.dhii.asia Book of Abstracts The 18th Annual TEI Conference Hosted by: Center for Evolving Humanities, Graduate School of and Members’ Meeting Humanities and Sociology, The University of Tokyo Joint Keynote Session JADH and TEI Joint Keynote Session The NIJL Database of Pre-modern Japanese Works .................................................. iv Robert Campbell Amsterdam 4D: Navigating the History of Urban Creativity through Space and Time .......................................................................................................................................... v Julia Noordegraaf Creating Collections of Social Relevance ................................................................... vii Susan Schreibman iii Joint Keynote Session The NIJL Database of Pre-modern Japanese Works Robert Campbell1 Abstract NIJL (the National Insitute of Japanese Literature) is currently engaged in digitizing, tagging and developing new ways to search the uniquely rich heritage of pre-modern (prior to -

An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar

.............................................................................................................................................................................................................WORK IN PROGESS WORK IN PROGRESS TOMASZ PACIORKOWSKI DOI: 10.15290/CR.2018.23.4.05 Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar Abstract. Gibraltar, popularly known as “The Rock”, has been a British overseas territory since the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1713. The demographics of this unique colony reflect its turbulent past, with most of the population being of Spanish, Portuguese or Italian origin (Garcia 1994). Additionally, there are prominent minorities of Indians, Maltese, Moroccans and Jews, who have also continued to influence both the culture and the languages spoken in Gibraltar (Kellermann 2001). Despite its status as the only English overseas territory in continental Europe, Gibraltar has so far remained relatively neglected by scholars of sociolinguistics, new dialect formation, and World Englishes. The paper provides a summary of the current state of sociolinguistic research in Gibraltar, focusing on such aspects as identity formation, code-switching, language awareness, language attitudes, and norms. It also delineates a plan for further research on code-switching and national identity following the 2016 Brexit referendum. Keywords: Gibraltar, code-switching, sociolinguistics, New Englishes, dialect formation, Brexit. 1. Introduction Gibraltar is located on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula and measures just about 6 square kilometres. This small size, however, belies an extraordinarily complex political history and social fabric. In the Brexit referendum of 23rd of June 2016, the inhabitants of Gibraltar overwhelmingly expressed their willingness to continue belonging to the European Union, yet at the moment it appears that they will be forced to follow the decision of the British govern- ment and leave the EU (Garcia 2016). -

Php Editor Mac Freeware Download

Php editor mac freeware download Davor's PHP Editor (DPHPEdit) is a free PHP IDE (Integrated Development Environment) which allows Project Creation and Management, Editing with. Notepad++ is a free and open source code editor for Windows. It comes with syntax highlighting for many languages including PHP, JavaScript, HTML, and BBEdit costs $, you can also download a free trial version. PHP editor for Mac OS X, Windows, macOS, and Linux features such as the PHP code builder, the PHP code assistant, and the PHP function list tool. Browse, upload, download, rename, and delete files and directories and much more. PHP Editor free download. Get the latest version now. PHP Editor. CodeLite is an open source, free, cross platform IDE specialized in C, C++, PHP and ) programming languages which runs best on all major Platforms (OSX, Windows and Linux). You can Download CodeLite for the following OSs. Aptana Studio (Windows, Linux, Mac OS X) (FREE) Built-in macro language; Plugins can be downloaded and installed from within jEdit using . EditPlus is a text editor, HTML editor, PHP editor and Java editor for Windows. Download For Mac For macOS or later Release notes - Other platforms Atom is a text editor that's modern, approachable, yet hackable to the core—a tool. Komodo Edit is a simple, polyglot editor that provides the basic functionality you need for programming. unit testing, collaboration, or integration with build systems, download Komodo IDE and start your day trial. (x86), Mac OS X. Download your free trial of Zend Studio - the leading PHP Editor for Zend Studio - Mac OS bit fdbbdea, Download. -

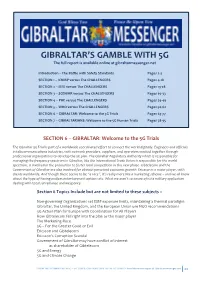

Gibraltar-Messenger.Net

GIBRALTAR’S GAMBLE WITH 5G The full report is available online at gibraltarmessenger.net Introduction – The Battle with Safety Standards Pages 2-3 SECTION 1 – ICNIRP versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 4-18 SECTION 2 – IEEE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 19-28 SECTION 3 – SCENIHR versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 29-33 SECTION 4 – PHE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 34-49 SECTION 5 – WHO versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 50-62 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials Pages 63-77 SECTION 7 – GIBRALTARIANS: Welcome to the 5G Human Trials Pages 78-95 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials The Gibraltar 5G Trial is part of a worldwide coordinated effort to connect the world digitally. Engineers and officials in telecommunications industries, with network providers, suppliers, and operators worked together through professional organizations to develop the 5G plan. The Gibraltar Regulatory Authority which is responsible for managing the frequency spectrum in Gibraltar, like the International Trade Union is responsible for the world spectrum, is involved in the promotion to foster local competition in this new phase. Gibtelecom and the Government of Gibraltar are also involved for obvious perceived economic growth. Ericsson is a major player, with clients worldwide. And though there seems to be “a race”, it’s really more like a marketing scheme – and we all know about the hype of having endless entertainment options etc. What we aren’t so aware of is its military application dealing with total surveillance and weaponry. Section 6 Topics Include but -

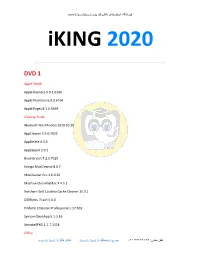

Iking 2020 Daneshland.Pdf

ﻓروﺷﮕﺎه ایﻧﺗرﻧتی داﻧش ﻟﻧد www.Daneshland.com iKING 2020 ├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ DVD 1 Apple iWork Apple Keynote 9.0.1.6196 Apple Numbers 6.0.0.6194 Apple Pages 8.1.0.6369 Cleanup Tools Abelssoft WashAndGo 2020 20.20 AppCleaner 3.5.0.3922 AppDelete 4.3.3 AppZapper 2.0.2 BlueHarvest 7.2.0.7025 Koingo MacCleanse 8.0.7 MacCleaner Pro 1.6.0.26 MacPaw CleanMyMac X 4.5.2 Northern Soft Catalina Cache Cleaner 15.0.1 OSXBytes iTrash 5.0.3 Piriform CCleaner Professional 1.17.603 Synium CleanApp 5.1.3.16 UninstallPKG 1.1.7.1318 Office ﺗﻠﻔن ﺗﻣﺎس: ۶۶۴۶۴۱۲۳-۰۲۱ پیج ایﻧﺳﺗﺎﮔرام: danesh_land ﮐﺎﻧﺎل ﺗﻠﮕرام: danesh_land ﻓروﺷﮕﺎه ایﻧﺗرﻧتی داﻧش ﻟﻧد www.Daneshland.com DEVONthink Pro 3.0.3 LibreOffice 6.3.4.2 Microsoft Office 2019 for Mac 16.33 NeoOffice 2017.20 Nisus Writer Pro 3.0.3 Photo Tools ACDSee Photo Studio 6.1.1536 ArcSoft Panorama Maker 7.0.10114 Back In Focus 1.0.4 BeLight Image Tricks Pro 3.9.712 BenVista PhotoZoom Pro 7.1.0 Chronos FotoFuse 2.0.1.4 Corel AfterShot Pro 3.5.0.350 Cyberlink PhotoDirector Ultra 10.0.2509.0 DxO PhotoLab Elite 3.1.1.31 DxO ViewPoint 3.1.15.285 EasyCrop 2.6.1 HDRsoft Photomatix Pro 6.1.3a IMT Exif Remover 1.40 iSplash Color Photo Editor 3.4 JPEGmini Pro 2.2.3.151 Kolor Autopano Giga 4.4.1 Luminar 4.1.0 Macphun ColorStrokes 2.4 Movavi Photo Editor 6.0.0 ﺗﻠﻔن ﺗﻣﺎس: ۶۶۴۶۴۱۲۳-۰۲۱ پیج ایﻧﺳﺗﺎﮔرام: danesh_land ﮐﺎﻧﺎل ﺗﻠﮕرام: danesh_land ﻓروﺷﮕﺎه ایﻧﺗرﻧتی داﻧش ﻟﻧد www.Daneshland.com NeatBerry PhotoStyler 6.8.5 PicFrame 2.8.4.431 Plum Amazing iWatermark Pro 2.5.10 Polarr Photo Editor Pro 5.10.8 -

Wednesday 17Th March 2021

P R O C E D I N G S O F T H E G I B R A L T A R P A R L I A M E N T AFTERNOON SESSION: 3.40 p.m. – 7.40 p.m. Gibraltar, Wednesday, 17th March 2021 Contents Questions for Oral Answer ..................................................................................................... 3 Employment, Health and Safety and Social Security........................................................................ 3 Q519/2020 Health and safety inspections at GibDock – Numbers in 2019 and 2020 ............. 3 Q520/2020 Maternity grants and allowances – Reason for delays in applications ................. 3 Q521/2020 Carers’ allowance – How to apply ......................................................................... 5 Environment, Sustainability, Climate Change and Education .......................................................... 6 Q547/2021 Dog fouling – Number of fines imposed ................................................................ 6 Q548-50/2020 Barbary macaques – Warning signs and safety measures ............................... 7 Q551/2020 Governor’s Street – Tree planting ......................................................................... 8 Q552/2020 School buses – Rationale for cancelling ................................................................ 9 Q553/2020 Fly tipping – Number of complaints and prosecutions ......................................... 9 Q554/2020 Waste Treatment Plan – Update ......................................................................... 11 Q555/2020 Water production – Less energy-intensive -

Why the U.S. Should Back British Sovereignty Over Gibraltar Luke Coffey

BACKGROUNDER No. 2879 | FEBRUARY 13, 2014 Self-Determination and National Security: Why the U.S. Should Back British Sovereignty over Gibraltar Luke Coffey Abstract The more than three-centuries-long dispute between Spain and Key Points the United Kingdom over the status of Gibraltar has been heating up again. The U.S. has interests at stake in the dispute: It benefits n Gibraltar’s history is important, from its close relationship with Gibraltar as a British Overseas Ter- and the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht ritory. The Anglo–American Special Relationship means that the is clear that Gibraltar is British today, but most important is U.S. enjoys access to British overseas military bases unlike any other the right of the Gibraltarians to country in the world. From America’s first overseas military inter- self-determination. vention in 1801 against the Barbary States to the most recent military n Since 1801, the U.S. has ben- overseas intervention in 2011 against Qadhafi’s regime in Libya, the efited from its relationship with U.S. has often relied on Gibraltar’s military facilities. An important Gibraltar as a British Overseas part of the Gibraltar dispute between the U.K. and Spain is the right Territory in a way that would not of self-determination of the Gibraltarians—a right on which America be possible with Gibraltar under was founded, and a right that Spain regularly ignores. Spain is an Spanish control. British control of important NATO ally, and home to several U.S. military installations, Gibraltar ensures virtually guar- but its behavior has a direct impact on the effectiveness of U.S. -

Multiculturalism in the Creation of a Gibraltarian Identity

canessa 6 13/07/2018 15:33 Page 102 Chapter Four ‘An Example to the World!’: Multiculturalism in the Creation of a Gibraltarian Identity Luis Martínez, Andrew Canessa and Giacomo Orsini Ethnicity is an essential concept to explain how national identities are articulated in the modern world. Although all countries are ethnically diverse, nation-formation often tends to structure around discourses of a core ethnic group and a hegemonic language.1 Nationalists invent a dominant – and usually essentialised – narrative of the nation, which often set aside the languages, ethnicities, and religious beliefs of minori- ties inhabiting the nation-state’s territory.2 In the last two centuries, many nation-building processes have excluded, removed or segregated ethnic groups from the national narrative and access to rights – even when they constituted the majority of the population as in Bolivia.3 On other occasions, the hosting state assimilated immigrants and ethnic minorities, as they adopted the core-group culture and way of life. This was the case of many immigrant groups in the USA, where, in the 1910s and 1920s, assimilation policies were implemented to acculturate minorities, ‘in attempting to win the immigrant to American ways’.4 In the 1960s, however, the model of a nation-state as being based on a single ethnic group gave way to a model that recognised cultural diver- sity within a national territory. The civil rights movements changed the politics of nation-formation, and many governments developed strate- gies to accommodate those secondary cultures in the nation-state. Multiculturalism is what many poly-ethnic communities – such as, for instance, Canada and Australia – used to redefine their national identi- ties through the recognition of internal cultural difference. -

Tuesday 11Th June 2019

P R O C E E D I N G S O F T H E G I B R A L T A R P A R L I A M E N T MORNING SESSION: 10.01 a.m. – 12.47 p.m. Gibraltar, Tuesday, 11th June 2019 Contents Appropriation Bill 2019 – For Second Reading – Debate continued ........................................ 2 The House adjourned at 12.47 p.m. ........................................................................................ 36 _______________________________________________________________________________ Published by © The Gibraltar Parliament, 2019 GIBRALTAR PARLIAMENT, TUESDAY, 11th JUNE 2019 The Gibraltar Parliament The Parliament met at 10.01 a.m. [MR SPEAKER: Hon. A J Canepa CMG, GMH, OBE, in the Chair] [CLERK TO THE PARLIAMENT: P E Martinez Esq in attendance] Appropriation Bill 2019 – For Second Reading – Debate continued Clerk: Tuesday, 11th June 2019 – Meeting of Parliament. Bills for First and Second Reading. We remain on the Second Reading of the Appropriation 5 Bill 2019. Mr Speaker: The Hon. Dr John Cortes. Minister for the Environment, Energy, Climate Change and Education (Hon. Dr J E Cortes): Good morning, Mr Speaker. I rise for my eighth Budget speech conscious that being the last one in the electoral cycle it could conceivably be my last. While resisting the temptation to summarise the accomplishments of this latest part of my life’s journey, I must however comment very briefly on how different Gibraltar is today from an environmental perspective. In 2011, all you could recycle here was glass. There was virtually no climate change awareness, no possibility of a Parliament even debating let alone passing a motion on the climate emergency. -

H. Corson Bremer Email: [email protected] Technical Communicator

FAX: (+33) (0)2.72.68.58.93 H. Corson Bremer Email: [email protected] Technical Communicator Nationality: Double nationality: American and French SKILLS Media & Communications: Writer, editor, and translator of end-user technical documents, manuals, online help, and training and promotional materials concerning documentation in IT, Telecommunications, Medical Technology, and Finance, among others. Voice Actor for corporate, Internet, general market, radio, and TV projects. Skilled in recorded and broadcast communications. Video & Audio Producer, writer, & director of multimedia in English. Information Mapping: General concepts and applied experience (i.e., No formal training). Structured Documentation: HTML, SGML, XHTML, XML, XSL (notions), DocBook (notions), DITA (notions). Read and speak French. Micro-computing: Structured Document management: XML, HTML, XSL, JavaScript, CSS, and version management. Knowledge (w/o work experience) of DITA and DocBook. Software use experience: Windows 95/98/NT/2000/XP: MS-Office Pro, Framemaker+SGML, Interleaf (Quicksilver), RoboHelp Office X3, Doc-to-Help 6.0, OpenOffice, Adept/Epic Editor, oXygen XML Editor, Adobe Acrobat, Adobe Master Collection (Illustrator, Photoshop, Dreamweaver, etc.), Paint Shop Pro, Camtasia, Adobe Audition, Sound Forge, Pro Tools, and others. LINUX/UNIX: Framemaker, Interleaf, Netscape, WebWorks Publisher, and others. Macintosh: MS-Office, Framemaker, Photoshop, Acrobat, and others. PROFESSIONAL HIGHLIGHTS (in France) April 2009 – Present Freelance Consultant in Technical Writing and Voice Acting: Self Employed; Neuf- Marché, France : Client: Big Wheels Studio, Montreuil, France. Duration: 1 day. Project: “Demo level Adrift - DontNod Productions”. English “Voice off” interpretation for 7 video game characters. Client: Reuters Financial Software, Puteux {Paris], France. Duration: 5 months. Project: Kondor+ Trade Processing documentation set: Creation and updating of user documentation for banking and trading risk management software. -

A Tale of Four Caves: Esr Dating of Mousterian Layers at Iberian Archaeological Sites

A TALE OF FOUR CAVES A TALE OF FOUR CAVES: ESR DATING OF MOUSTERIAN LAYERS AT IBERIAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES BY VITO VOLTERRA, M. A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctorate of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Vito Volterra, May, 2000 . DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (2000) McMaster University (Anthropology) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: A Tale of Four Caves: ESR Dating of Mousterian Layers at Iberian Archaeological Sites AUTHOR: Vito Volterra, M. A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor H. P. Schwarcz NUMBER OF PAGES: xviii, 250 Abstract This study was undertaken to provide supporting evidence for the late presence of Neanderthals in Iberia at the end of the Middle Paleolithic. This period is almost impossible to date accurately by the conventional radiocarbon method. Accordingly electron spin resonance (ESR) was used to obtain ages for four Spanish sites. They were EI Pendo in the Cantabrian north, Carihuela in Andalusia and Gorham's and Vanguard caves at Gibraltar. The sites were chosen to allow the greatest variety in geographic settings, latitudes and sedimentation. They were either under exca vation or had been excavated recently following modem techniques. A multidisciplinary approach to dating the archaeological contexts was being proposed for all the sites except EI Pendo whose deposits had been already dated but only on the basis ofsedimentological and faunal analyses. This was the first research program to apply ESR to such a variety ofsites and compare its results with that ofsuch a variety of other archaeometric dating teclmiques. The variety allowed a further dimension to the research that is the opportunity ofappraising first hand the applicability and advantages ofa new dating technique and determining its accuracy as an archaeological dating method incomparison with other techniques.