Religious Freedom in Prison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Naming Conventions NAFSA TX State Mtg

1 2 3 4 1. Transcription is a more phonetic interpretation, while transliteration represents the letters exactly 2. Why transcription instead of transliteration? • Some English vowel sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some English consonant sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some languages are not written with letters 3. What issues are related to transcription and transliteration? • Lack of consistent rules from some languages or varying sets of rules • Country variation in choice of rules • Country/regional variations in pronunciation • Same name may be transcribed differently even within the same family • More confusing when common or religious names cross over several countries with different scripts (i.e., Mohammad et al) 5 Dark green countries represent those countries where Arabic is the official language. Lighter green represents those countries in which Arabic is either one of several official languages or is a language of everyday usage. Middle East and Central Asia: • Kurdish and Turkmen in Iraq • Farsi (Persian) and Baluchi in Iran • Dari, Pashto and Uzbek in Afghanistan • Uyghur, Kazakh and Kyrgyz in northwest China South Asia: • Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Baluchi in Pakistan • Urdu and Kashmiri in India Southeast Asia: • Malay in Burma • Used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, southern Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines Africa: • Bedawi or Beja in Sudan • Hausa in Nigeria • Tamazight and other Berber languages 6 The name Mohamed is an excellent example. The name is literally written as M‐H‐M‐D. However, vowels and pronunciation depend on the region. D and T are interchangeable depending on the region, and the middle “M” is sometimes repeated when transcribed. -

Religious and Cultural Beliefs

Document Type: Unique Identifier: GUIDELINE CORP/GUID/027 Title: Version Number: Religious and Cultural Beliefs 4 Status: Ratified Target Audience: Divisional and Trust Wide Department: Patient Experience Author / Originator and Job Title: Risk Assessment: Rev Jonathan Sewell, Chaplaincy Team Leader in consultation Not Applicable with Chaplaincy colleagues and representatives of local faith communities Replaces: Description of amendments: Version 3 Religious and Cultural Beliefs Updated information CORP/GUID/027 Validated (Technical Approval) by: Validation Date: Which Principles Chaplaincy Department Meeting 26/05/2016 of the NHS Chaplaincy Team Meeting 23/06/16 Constitution Apply? 3 Ratified (Management Approval) by: Ratified Date: Issue Date: Patient and Carer Experience and 18/07/2016 18/07/2016 Involvement Committee Review dates and version numbers may alter if any significant Review Date: changes are made 01/06/2019 Blackpool Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust aims to design and implement services, policies and measures that meet the diverse needs of our service, population and workforce, ensuring that they are not placed at a disadvantage over others. The Equality Impact Assessment Tool is designed to help you consider the needs and assess the impact of your policy in the final Appendix. CONTENTS 1 Purpose ....................................................................................................................... 3 2 Target Audience ......................................................................................................... -

AACR2: Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, 2Nd Ed. 2002 Revision

Cataloguing Code Comparison for the IFLA Meeting of Experts on an International Cataloguing Code July 2003 AACR2: Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, 2nd ed. 2002 revision. - Ottawa : Canadian Library Association ; London : Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals ; Chicago : American Library Association, 2002. AAKP (Czech): Anglo-americká katalogizační pravidla. 1.české vydání. – Praha, Národní knihovna ČR, 2000-2002 (updates) [translated to Czech from Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, 2nd ed. 2002 revision. - Ottawa : Canadian Library Association ; London : Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals ; Chicago : American Library Association, 2002. AFNOR: AFNOR cataloguing standards, 1986-1999 [When there is no answer under a question, the answer is yes] BAV: BIBLIOTECA APOSTOLICA VATICANA (BAV) Commissione per le catalogazioni AACR2 compliant cataloguing code KBARSM (Lithuania): Kompiuterinių bibliografinių ir autoritetinių įrašų sudarymo metodika = [Methods of Compilation of the Computer Bibliographic and Authority Records] / Lietuvos nacionalinė Martyno Mažvydo biblioteka. Bibliografijos ir knygotyros centras ; [parengė Liubovė Buckienė, Nijolė Marinskienė, Danutė Sipavičiūtė, Regina Varnienė]. – Vilnius : LNB BKC, 1998. – 132 p. – ISBN 9984 415 36 5 REMARK: The document presented above is not treated as a proper complex cataloguing code in Lithuania, but is used by all libraries of the country in their cataloguing practice as a substitute for Russian cataloguing rules that were replaced with IFLA documents for computerized cataloguing in 1991. KBSDB: Katalogiseringsregler og bibliografisk standard for danske biblioteker. – 2. udg.. – Ballerup: Dansk BiblioteksCenter, 1998 KSB (Sweden): Katalogiseringsregler för svenska bibliotek : svensk översättning och bearbetning av Anglo-American cataloguing rules, second edition, 1988 revision / utgiven av SAB:s kommitté för katalogisering och klassifikation. – 2nd ed. – Lund : Bibliotekstjänst, 1990. -

Research Article

s z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 11, Issue, 02, pp.1239-1242, February, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24941/ijcr.34099.02.2019 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE NAMES OF PEOPLE ASSOCIATED WITH RELIGIOUS CONCEPTS 1,*Rysbayeva, G., 2Bainesh Sh. 3Kulbekova, B., 4Manabaev, B., 5Orazbaeva, H. and 6Baktiyarova Sh. 1Doctor of Philology, Nur-Mubarak Egyptian University of Islamic Culture 2Doctor of Pedagogy, Nur-Mubarak Egyptian University of Islamic Culture 3Candidate of Pedagogy, Nur-Mubarak Egyptian University of Islamic Culture 4PhD Doctor, Nur-Mubarak Egyptian University of Islamic Culture 5Senior Teacher, Nur-Mubarak Egyptian University of Islamic Culture 6Master of Philology, Nur-Mubarak Egyptian University of Islamic Culture ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: A religious name is a type of given name bestowed for a religious purpose, and which is generally Received 05th November, 2018 used in religious contexts. Different types of religious names may be in use among clergy of a Received in revised form religion, as well in some cases among the laity. Now consider the language picture of the world in 24th December, 2018 general human cognition in the unity of the world model, and with the same conceptual view of the Accepted 20th January, 2019 th world is a philosophical and philological concept. The study "Language world" and "Conceptual Published online 28 February, 2019 picture of the world" in the trinity "Language-thought-world" is one of the urgent problems of modern linguistics. Language world - a specific method for the language of reflection and representation of Key Words: reality in language forms and structures in its relation with the person who is the central figure of the Religion, Totemism, Animism, Conceptual language. -

Onomastics Between Sacred and Profane

Onomastics between Sacred and Profane Edited by Oliviu Felecan Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, North University Center of Baia Mare, Romania Series in Language and Linguistics Copyright © 2019 Vernon Press, an imprint of Vernon Art and Science Inc, on behalf of the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Language and Linguistics Library of Congress Control Number: 2018951085 ISBN: 978-1-62273-401-6 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Table of Contents Foreword vii Acknowledgments xxi Contributors xxiii Preface xxv Part One: Onomastic Theory. Names of God(s) in Different Religions/Faiths and Languages 1 Chapter 1 God’s Divine Names in the Qur’aan : Al-Asmaa' El-Husna 3 Wafa Abu Hatab Chapter 2 Planning the Name of God and the Devil. -

Annotated Bibliography: Baptism in Times of Change in the Nordic Region 2000-2020

Annotated Bibliography: Baptism in Times of Change in the Nordic Region 2000-2020 Editors: Harald Hegstad, Jonas Adelin Jørgensen, Karin Tillberg, Steinunn Bjornsdottir, Jyri Komulainen, Hanna Salomäki Publisher: Interchurch Council of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Denmark, Copenhagen, 2021 The following is an annotated bibliography for statistics, discussions, and reports on baptism in the Nordic Lutheran folk churches in the period from 2000 to 2020. A short abstract is provided for each entry and an evaluation in italics. For more information on the project on baptism and downloadable data files, please visit the homepage www.churchesintimesofchange.org Table of Content: 1. Statistics ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Denmark .................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Finland ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Iceland ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Norway .................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Sweden ................................................................................................................................................... -

Allocation of New Top-Level Domain Names and the Effect Upon Religious Freedom

THE JOHN MARSHALL REVIEW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW ALLOCATION OF NEW TOP-LEVEL DOMAIN NAMES AND THE EFFECT UPON RELIGIOUS FREEDOM N. CAMERON RUSSELL ABSTRACT The monopoly provided when trademark protection is given to a religious name is in direct tension with an individual’s right to freedom of religion. One’s ability to freely use a particular religious name in spiritual practice, and to identify one’s belief system with the words that commonly describe it, are weakened when trademark law designates just one owner. This Article explores the impact of the impending issuance of brand new top-level domains utilizing religious names, and how the providing of an exclusive right for one entity to govern over a religious top-level domain, in addition to the existence of a trademark monopoly held upon the same name, may affect the vigor of freedoms of religion and speech. This Article argues that there should be a presumption against trademark protection of religious names in order to reaffirm constitutional freedoms, and that the implementation of such a presumption within U.S. law will have the additional benefit of improving an imperfect judicial framework for analyzing trademark cases involving religious names. The Article concludes by proposing some specific rules for implementation of such a presumption, as well as some comparative remarks juxtaposing the solution proposed by this Article with public policy objectives and the discourse within the international community. Copyright © 2013 The John Marshall Law School Cite as N. Cameron Russell, Allocation of New Top-Level Domain Names and the Effect Upon Religious Freedom, 12 J. -

German Naming Conventions a Good Understanding of the Conventions Used by German Families for Naming Children Is Essential to German Genealogy Research

She has the Same Name Is She her Sister? Naming Conventions of our Ancestors Nancy Waters Lauer [email protected] Fires that destroyed census records, court house records, and church and cemetery records present obstacles for genealogists that have tested us for years. Equal to these challenges are the numerous naming conventions used by our ancestors. Growing up in a society that bestows first, middle, and last names to children, it is often unnerving to discover all cultures don’t conform to this rule. Why did Uncle Albert name all his daughters Maria? Why would I search on someone’s middle name to locate their record? How many Christiana’s can one family have? These are just a few of the questions that plague beginning as well as seasoned researchers. Not only did our ancestors bring their families to America, they brought their language, traditions, and customs. German Naming Conventions A good understanding of the conventions used by German families for naming children is essential to German genealogy research. This knowledge helps identify family relationships and explains multiple children with similar or, in some cases, the same name. Both Catholic and Protestant religions adopted this method of naming children. Customarily at baptism a child was given two names. The first was a religious name and the second their call (Rufnahme) name. Unlike today, people were known by their second or middle name. Johann Ludwig Steck was called Ludwig or Louis. However, he can be located in various records as Johann, John, Ludwig, and Louis. Families often used the same saint’s name for most or all their children’s first names. -

A Guide to Names and Naming Practices

March 2006 AA GGUUIIDDEE TTOO NN AAMMEESS AANNDD NNAAMMIINNGG PPRRAACCTTIICCEESS This guide has been produced by the United Kingdom to aid with difficulties that are commonly encountered with names from around the globe. Interpol believes that member countries may find this guide useful when dealing with names from unfamiliar countries or regions. Interpol is keen to provide feedback to the authors and at the same time develop this guidance further for Interpol member countries to work towards standardisation for translation, data transmission and data entry. The General Secretariat encourages all member countries to take advantage of this document and provide feedback and, if necessary, updates or corrections in order to have the most up to date and accurate document possible. A GUIDE TO NAMES AND NAMING PRACTICES 1. Names are a valuable source of information. They can indicate gender, marital status, birthplace, nationality, ethnicity, religion, and position within a family or even within a society. However, naming practices vary enormously across the globe. The aim of this guide is to identify the knowledge that can be gained from names about their holders and to help overcome difficulties that are commonly encountered with names of foreign origin. 2. The sections of the guide are governed by nationality and/or ethnicity, depending on the influencing factor upon the naming practice, such as religion, language or geography. Inevitably, this guide is not exhaustive and any feedback or suggestions for additional sections will be welcomed. How to use this guide 4. Each section offers structured guidance on the following: a. typical components of a name: e.g. -

Naming Names

NAMING NAMES A DISCUSSION ABOUT DATA-ENTRY FIELD LABELS FOR PERSONAL NAME COMPONENTS It is an unfortunate fact that most data-entry forms on the Internet fail to take advantage of the dynamic medium, so that a single form layout is used regardless of the place of residence or cultural background of the person filling in the form. Equally unfortunate is that the fixed form that most data entry forms have has been defined by the cultural norms of the society in which the form or site were set up. The same can be said of field labels, and this document discusses labels used for personal name components in English. PREFIX, FIRST NAME, FORENAME, MIDDLE NAME, LAST NAME, SUFFIX Look for an English-language definition of given name, surname or family name, and you will often be told that a given name is synonymous with first name whilst surname or family name are synonymous with each other and with last name. Any definition which indicates a relative positioning of a name component, such as prefix, first name, last name or suffix is culturally defined. It reflects the predominant name ordering in Anglo-Saxon societies such as the USA and the UK, and fails to take into account different naming patterns across the world. A majority of the world’s population order their names differently, putting, for example, the surname/family name before the given name(s). This being the case, field labels such as prefix, first name, last name or suffix must never be used on a data- entry form being used by an international audience. -

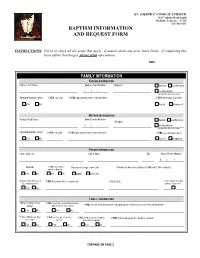

Baptism Request Form

ST. JOSEPH CATHOLIC CHURCH 1225 Gallatin Road South Madison, Tennessee 37115 615-865-1071 BAPTISM INFORMATION AND REQUEST FORM INSTRUCTIONS: Fill in or check all the areas that apply. If unsure about any area, leave blank. If completing this form offline (hardcopy), please print information. Date: FAMILY INFORMATION FATHER INFORMATION Father’s Full Name: Main Contact Number: Religion: Baptism Confirmation ( ) - Holy Eucharist Sacraments: check all received. Attended baptism class? If YES, list year: If YES, give parish name, city and state: If YES, what was your role? Yes No Parent Godparent MOTHER INFORMATION Mother’s Full Name: Main Contact Number: Baptism Confirmation Religion: ( ) - Holy Eucharist Sacraments: check all received. Attended baptism class? If YES, list year: If YES, give parish name, city and state: If YES, you attended as a: Yes No Parent Godparent PARENT INFORMATION Home Address: City & State: Zip: Home Phone Number ( ) - If YES, married by Married? If not married, single or divorced? If divorced, who has custody of child(ren)? Give name(s): priest or deacon? Yes No Yes No Single Divorced Registered member(s) of If NO, list parish where registered: City & State: If not registered at any St. Joseph’s parish? parish, check here. Yes No FAMILY INFORMATION Other children in the If YES, have they received sacraments If NO, do you need assistance in preparing the children to receive their sacraments? family? appropriate for their ages? Yes No Yes No If other children, are they If YES, do they go to Catholic If NO, do they attend a Catholic If YES, list the program the child(ren) attend: school age? school? Education Program? Yes No Yes No Yes No CONTINUE ON PAGE 2 Baptism Information and Request Form Page 2 St. -

Internationalisation People Names

Internationalisation of People Names Submitted to the UNIVERSITY of LIMERICK for the degree of MASTER of SCIENCE Gary Lefman Supervised by Dr. Richard Sutcliffe COLLEGE of INFORMATICS and ELECTRONICS Department of Computer Science and Information Systems September 2013 This page is intentionally blank Abstract Title: Internationalisation of People Names Author: Gary Lefman If a system does not possess the ability to capture, store, and retrieve people names, according to their cultural requirements, it is less likely to be acceptable on the international market. Internationalisation of people names could reduce the probability of a person’s name being lost in a system, avoiding frustration, saving time, and possibly money. This study attempts to determine the extent to which the human name can be internationalised, based upon published anthroponymic data for 148 locales, by categorising them into eleven distinctly autonomous parts: definite article, common title, honorific title, nickname, by-name, particle, forename, patronymic or matronymic, surname, community name, and generational marker. This paper provides an evaluation of the effectiveness of internationalising people names; examining the challenges of terminology conflicts, the impact of subjectivity whilst pigeonholing personyms, and the consequences of decisions made. It has demonstrated that the cultural variety of human names can be expressed with the Locale Data Mark-up Language for 74% of the world’s countries. This study, which spans 1,919 anthroponymic syntactic structures, has also established, through the use of a unique form of encoding, that the extent to which the human name can be internationalised is 96.31% of the data published by Plassard (1996) and Interpol (2006).