Getting Real: a New Interpretation of NASCAR's Folklore and Mythology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0605 AARWBA.P65

ImPRESSions© The Official Newsletter Of The American Auto Racing Writers and Broadcasters Association June 2005 Vol. 38 No. 5 AARWBA Thanks Our Official 50th Anniversary Sponsors: (Click on any logo to go to that sponsor’s website!) American Auto Racing Writers & Broadcasters Association Journalism and Photo Contest winners posted now at http://beta.motorsportsforum.com/ris01/aarwbawi.htm France Family Voted Newsmaker of the Half-Century 842-7005 Original painting by AARWBA member Hector Cademartori - IMS photo by Ron McQueeney The France Family, whose vision and leadership turned NASCAR stock car racing from a loosely-organized Southern-based attraction into the country’s second-most popular sport, was named Newsmaker of the Half- Century by the American Auto Racing Writers and Broadcasters Association during the annual AARWBA members breakfast in Indianapolis May 28. Newsmaker of the Half-Century, determined by vote of AARWBA members, is the most important event of AARWBA’s 50th Anniversary Celebration. The France family received 28.5 percent of the vote among 12 nominees for the award. A record number of AARWBA members participated, according to President Dusty Brandel. The Hulman-George family, owner of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and responsible for building the Indy 500 into the world’s largest single- day sporting spectacle, finished second in the voting with 26.3 percent. The two families combined to capture almost 55 percent of the total vote. Lesa France Kennedy, president of International Speedway Corp., was present for the announcement. She accepted a specially commissioned painting, by artist Hector Cademartori, depicting the family’s 50 years of achievement from Brandel and AARWBA 50th Anniversary Celebration Chairman Michael Knight. -

0805 AARWBA.P65

ImPRESSions© The Official Newsletter Of The American Auto Racing Writers and Broadcasters Association August 2005 Vol. 38 No. 7 AARWBA Thanks Our Official 50th Anniversary Sponsors: (Click on any logo to go to that sponsor’s website!) 36th annual All-America Team Dinner, Saturday, Dec. 3, Hyatt Regency in downtown Indianapolis NASCAR President Helton to be Featured Speaker At All-America Team Dinner, Dec. 3, in Indianapolis NASCAR President Mike Helton will be the featured speaker at the AARWBA’s 36th annual All-America Team dinner, Saturday, Dec. 3, at the Hyatt Re- gency in downtown Indianapolis. The dinner will mark the official conclusion of AARWBA’s 50th Anniversary Celebration. Helton will share his important insights with AARWBA members and guests in Indy one day after the annual NASCAR NEXTEL Cup awards cer- emony in New York City. Helton has been a key 842-7005 leader in growing NASCAR into America’s No. 1 motorsports series and one of the country’s most popular mainstream sports attractions. Before becoming NASCAR president in late 2000, Helton had management positions at the Atlanta and Talladega tracks, and later was NASCAR’s vice president for competition and then senior VP and chief operating officer. “I’m happy to accept AARWBA’s invitation to speak at the All-America Team dinner,” said Helton. “AARWBA members have played an important role in the growth of NASCAR and motorsports in general. I look forward to this opportunity, and to join AARWBA in recognizing the champion drivers of 2005, and congratulating AARWBA on a successful 50th anniversary.” AARWBA members voted NASCAR’s founding France Family as Newsmaker of the Half-Cen- tury, the headline event of the 50th Anniversary Celebration. -

MIKE JOY Race Announcer, FOX NASCAR

MIKE JOY Race Announcer, FOX NASCAR Broadcasting veteran Mike Joy brings 50 years of motor sports experience to the booth as lead race announcer for FOX NASCAR in 2020, his 20th consecutive season with the network, alongside NASCAR Hall of Famer Jeff Gordon. Joy has led the network’s broadcast team since 2001, FOX’s first year as a NASCAR broadcast partner. Joy has broadcast most major forms of American motorsports for television and radio. Prior to joining FOX in 2001, Joy anchored CBS Sports’ coverage of the DAYTONA 500 from 1998-2000 after earning his stripes as a pit reporter for 15 years. In addition, Joy called the “Great American Race” for Motor Racing Network (MRN) Radio from 1977-’83 (as a turn announcer and anchor). The season-opening DAYTONA 500 marks the 41st DAYTONA 500 for which he has been part of live TV or radio coverage. In 2020, Joy covers his 45th Daytona Speedweeks. He is a charter member of the prestigious NASCAR Hall of Fame Voting Panel, and in December 2013, was named sole media representative on the Hall's exclusive Nominating Committee. Joy previously served on the voting panel for the International Motorsports Hall of Fame. Joy was the 2011 recipient of the esteemed Henry T. McLemore Motorsports Journalism Award, recognizing career excellence in the field, as well as the 2018 North Carolina Motorsports Association (NCMA) Jim Hunter Memorial Media Award. A former vice president of the National Motorsport Press Association, Joy joined Chris Economaki as the first racing journalists to receive major recognition for their work in all three major disciplines: radio, television and print. -

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0001 Victory Circle #4012, WG 1951 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0002 1959 Sports Car Grand Prix Weekend 1959 D-0003 A Gullwing at Twilight 1959 D-0004 At the IMRRC The Legacy of Briggs Cunningham Jr. 1959 D-0005 Legendary Bill Milliken talks about "Butterball" Nov 6,2004 1959 D-0006 50 Years of Formula 1 On-Board 1959 D-0007 WG: The Street Years Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1948 D-0008 25 Years at Speed: The Watkins Glen Story Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1972 D-0009 Saratoga Automobile Museum An Evening with Carroll Shelby D-0010 WG 50th Anniversary, Allard Reunion Watkins Glen, NY D-0011 Saturday Afternoon at IMRRC w/ Denise McCluggage Watkins Glen Watkins Glen October 1, 2005 2005 D-0012 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival Watkins Glen 2005 D-0013 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen 1952 D-0014 1951-54 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1951-54 D-0015 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend 1952 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1952 D-0016 Ralph E. Miller Collection Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1949 Watkins Glen 1949 D-0017 Saturday Aternoon at the IMRRC, Lost Race Circuits Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 2006 D-0018 2005 The Legends Speeak Formula One past present & future 2005 D-0019 2005 Concours d'Elegance 2005 D-0020 2005 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival, Smalleys Garage 2005 D-0021 2005 US Vintange Grand Prix of Watkins Glen Q&A w/ Vic Elford 2005 D-0022 IMRRC proudly recognizes James Scaptura Watkins Glen 2005 D-0023 Saturday -

V O L U M E 2 6 • E D I T I O N 1 8 . 4

VOLUME 26 • EDITION 18.4 • SPONSORED BY PORSCHE CLUB OF AMERICA VOLUME 26 • EDITION 18.4 • OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2018 THE DIFFERENCE IN BRAKING 16 FEATURES 16 Inagural Super Enduro at High Plains Raceway 20 PCA at Sebring: A Perspective 24 Sebring Race Track and Hendricks Field 30 Preparation is (almost) Everything 34 Isringhausen Racing THE FIRST CHOICE FOR CHAMPIONS 38 On the Cover: Matthew Goetzinger 40 E Class 911s at Road America & Victor Newman Photography 42 Remembering Ron Panoz & Dave Maraj 44 A Race Against Time 20 50 Famous American Race Car Driver MAXIMUM PERFORMANCE 54 A Day in the Life of a Scrut 56 Dale Teuty: Club Racer from the Beginning 60 Say it Ain’t So AND RELIABILITY 64 Wanna Race? How to Become a Club Racer 73 Porsche 992 911 Caught at Nurburgring ORDER COLUMNS 4 From the Chair 6 View From the Tower 8 Boots on the Ground THE PADS 10 Down to Business 12 Editorial License YOU NEED 14 Coaching Perspective 34 REMNANTS In Stock, All the Time, Shipped Free 32 2018 Club Racing Schedule 59 National Awards Banquet Announcement — February 29 WE’RE THE LARGEST U.S. PAGID RACING BRAKE PAD SUPPLIER, WITH THE MOST EXTENSIVE INVENTORY. 63 2018 PCA Club Racing National Sponsors 68 2018 PCA Club Racing Contingency Programs PAGID Racing Brake Pads are available in 70 2018 Hard Chargers many compounds to fi t most applications. 72 The Classifieds 74 Club Racing National Committee, Advertising Index, CRN Staff Call us now or use the PAGID Racing Brake Pad Quick Search on our website On the Cover: Photographer Victor Newman took this photo of Matthew Goetzinger at Road America. -

DAYTONA-SUPERBIRD AUTO CLUB WHEELS & DEALS Personal for Sale/ Want

July-August 2012 www.superbirdclub.com email: [email protected] Muscle Car and Corvette Nationals Aero Car Display – Chicago Area - November 17 & 18, 2012 Update - at present, we have 30 aero cars signed up to participate in the special display. There is room in the display area for about ten more aero cars. This show is 500 + muscle cars, all under one roof, indoors at the Donald Stephens Convention Center in Rosemont Illinois. Non judged entry is no charge. Hotels are right across the street. This will be a great way to cap off 2012. Concours cars to barn finds will be displayed. The police car “Dirty Bird” Superbird will be present, as well as aero race cars, and an unrestored Cyclone Spoiler II. John Borzych and Gene Lewis are going to display their sequential serial number Daytonas side by side for the first time ever. Some cars we are still in need of for display: - Petty Blue Superbird - Superbird convertible - Charger 500’s - Survivor Daytona - King Cobra We are not limited to these, so if you would like to join in on the fun, please contact Doug Schellinger at 414-687-2489 ot email to: [email protected] Online regististration is available at www.mcacn.com/entry.htm Show director Bob Ashton’s phone is 586-549-5291 and his email is [email protected] Did I mention that this is a fantastic event? Indy Event Recap Our return to the Brickyard 400 was a big success. There were about 40 cars this year, many of which were not present last year. -

Wbaltv Baltimore

5O Cents 1VcY+s1i'iY act Branch Y 100 THE BUSINESSWEEKr ' C ailt 60617 ,d10 'orce. Base :r.S- ATSA KEWS'?AP.` la R rcoKUNKY 24, 1964L Transcontinent sale approved, but stricter McCann -Erickson raps reps, says it wants ownership rules may follow 27 the best spots or else 46 Baseball rights bring over $13.5 million; CBS -TV affiliates aim for a bigger slice package plan still under study 32 of the network's income 56 COMPLETE INDEX PAGE 7 MAXIMUM RESPONSE -that's advert efficienc WBALTV BALTIMORE "MARYLAND'S NUMBER ONE CHANNEL OF COMMUNICATION" inirr NATIr1NAI I V DCDDFCCNTCII DV Cr1vIADn DCTDV T1IEFFIGIES A SERIES OF FRAMEABLE ADworld CLOSE -UPS! heerny 7v 7 (FOCALAL fo¡Ntf (Z, # 24 WTReffigy TV SERIES FROM WHEELING, WEST VIRGINIA Scan Zoo Animals, Inc., Los Angeles, California NEW TOWER ... 529,300 TV HOMES Greater WTRF -TV Wheeling /Steubenville Industrial Ohio Valley .. A lively buying audience spending 51/2 Billion Dollars Annually .. Merchandising ... Promotion ... Rated Favorite! WTRF -TV Wheeling! vatrf Iv Represented Nationally by 316,000 watts network color (RED EYED SET? Write for your frameable WIReffigies, our adworld rloseup series!) WHEELING 7, WEST VIRGINIA The longer spän of station structure measures its length in years of séry -' ice along the foundation of community understanding and r meable walls with ready access full length above this foun daily flow of people a-rid ideas. In Houston; DIMENSION: LEN CO2 POST-MIX STARWHEEL sodium citrate carbonation SIX -PAIS PHOSPHORIC ACID Reseals Pre -mix Tandemizing acidulant alkali -dilution American Bottins of Carbonated Beverages MULTI -CITY TV MARKET Whatever your business language, U. -

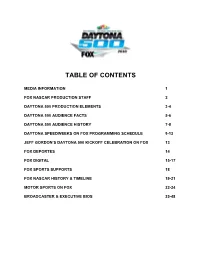

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

Racing, Region, and the Environment: a History of American Motorsports

RACING, REGION, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: A HISTORY OF AMERICAN MOTORSPORTS By DANIEL J. SIMONE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Daniel J. Simone 2 To Michael and Tessa 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A driver fails without the support of a solid team, and I thank my friends, who supported me lap-after-lap. I learned a great deal from my advisor Jack Davis, who when he was not providing helpful feedback on my work, was always willing to toss the baseball around in the park. I must also thank committee members Sean Adams, Betty Smocovitis, Stephen Perz, Paul Ortiz, and Richard Crepeau as well as University of Florida faculty members Michael Bowen, Juliana Barr, Stephen Noll, Joseph Spillane, and Bill Link. I respect them very much and enjoyed working with them during my time in Gainesville. I also owe many thanks to Dr. Julian Pleasants, Director Emeritus of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, and I could not have finished my project without the encouragement provided by Roberta Peacock. I also thank the staff of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program. Finally, I will always be grateful for the support of David Danbom, Claire Strom, Jim Norris, Mark Harvey, and Larry Peterson, my former mentors at North Dakota State University. A call must go out to Tom Schmeh at the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame, Suzanne Wise at the Appalachian State University Stock Car Collection, Mark Steigerwald and Bill Green at the International Motor Racing Resource Center in Watkins Glen, New York, and Joanna Schroeder at the (former) Ethanol Promotion and Information Council (EPIC). -

IPG Spring 2020 Auto & Motorcycle Titles

Auto & Motorcycle Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} The Brown Bullet Rajo Jack's Drive to Integrate Auto Racing Bill Poehler Summary The powers-that-be in auto racing in the 1920s, namely the American Automobile Association’s Contest Board, prohibited everyone who wasn’t a white male from the sport. Dewey Gaston, a black man who went by the name Rajo Jack, broke into the epicenter of racing in California, refusing to let the pervasive racism of his day stop him from competing against entire fields of white drivers. In The Brown Bullet, Bill Poehler uncovers the life of a long-forgotten trailblazer and the great lengths he took to even get on the track, and in the end, tells how Rajo Jack proved to a generation that a black man could compete with some of the greatest white drivers of his era, wining some of the biggest races of the day. Lawrence Hill Books 9781641602297 Pub Date: 5/5/20 Contributor Bio $28.99 USD Bill Poehler is an award-winning investigative journalist based in the northwest, where he has worked as a Discount Code: LON Hardcover reporter for the Statesman Journal for 21 years. His work has appeared in the Oregonian, the Eugene Register-Guard and the Corvallis Gazette-Times ; online at OPB.org and KGW.com; and in magazines including 240 Pages Carton Qty: 0 Slant Six News , Racing Wheels , National Speed Sport News and Dirt Track Digest . He lives in Salem, Oregon. Biography & Autobiography / Cultural Heritage BIO002010 9 in H | 6 in W How to be Formula One Champion Richard Porter Summary Are you the next Lewis Hamilton? How to be F1 Champion provides you with the complete guide to hitting the big time in top-flight motorsport, with advice on the correct look, through to more advanced skills such as remembering to insert 'for sure' at the start of every sentence, and tips on mastering the accents most frequently heard at press conferences. -

January (Winter) 2019

IAPSNJ Quarterly Magazine January ~ March 2019 Winter Edition Issue No. 41 A social, fraternal organization of more than 4,000 Italian American Law Enforcement officers in the State. William Schievella, President Editor-in-Chief Patrick Minutillo Visit us at http://www.iapsnj.org IAPSNJ Quarterly Magazine January ~ March 2019 Winter Edition Page 2 Issue No 41 P RESIDENT’ S MESSAGE B ILL S CHIEVELLA Detective Thomas officers for recognition at our SanFilippo, Jersey City Dinner Meetings directly to Police Department and me. We enjoy recognizing Officer Alex Monteleone, those that have gone above Palisades Park Police and beyond as law Department to the Board of enforcement officers. I can Officers. These five new be reached at board members are a great [email protected] addition to the current board I want to wish you and As you read this magazine of highly dedicated law your families a Healthy and we will be about to ring in the enforcement officers. Happy New Year. Please join New Year. For many of us, Organization’s like ours are us at a meeting or event in 2018 was full of vital because of the constant the coming year. accomplishments and influx of new talent to meet celebrations. This is the time the needs of our group. As of the year where we enjoy this Executive Board Fraternally yours, celebrating with colleagues, continues to serve the Italian William Schievella, President family and friends. As American and law Christmas and Hanukkah enforcement communities, I pass by us and the New Year always invite new members begins let’s use this as a time to become more involved. -

Bulletin North Carolina Region SCCA

January/February 2008 www.ncrscca.com January/February 2008 ® The Official Newsletter of the The Bulletin North Carolina Region SCCA As Our Outgoing RE Reflects on the ...Our Incoming RE Makes Plans for Past 3 Years... the Future by Mark Senior by Glenn Long Happy New Year and welcome one and all to what I feel will Having attended the SEDiv Annual meeting in Jekyll Island, be an exciting new season for the North Carolina Region. I’m Georgia on January 18-20, I wanted to share my perspective writing this article with mixed emotions, as this will be my and a few points of interest with you. First off, I was sincerely last one as your RE. While I look forward to stepping aside so impressed with the level of dedication and commitment by I can focus on my family and my racing (in that order!), I cer- everyone in attendance. Just like during our events, everyone tainly will miss all the people and activities that have made the there was willing to help a 'newby' navigate the terrain. past 3 years so rewarding. Saturday & Sunday I attended a meeting on Tech, one on I want to take this opportunity to thank everyone who has con- ECR's, another on SARRC, as well as, several of the director tributed to making my job easy, including: the members of and RE meetings. our Board of Directors who provide the real leadership and Phil Creighton, our new Area 12 Director and K.P. Jones, con- direction for our club; our Specialty Chiefs and others on the tinuing as Area 3 Director, welcomed us all, covered the meet- Comp Board who keep our events running like clockwork; our ing formats, gave a very general overview of the health of the Webmaster and Newsletter Editor who keep us all well in- club (which is very good, by the way) and sent us on our way.