View Full Text Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moluscos Del Perú

Rev. Biol. Trop. 51 (Suppl. 3): 225-284, 2003 www.ucr.ac.cr www.ots.ac.cr www.ots.duke.edu Moluscos del Perú Rina Ramírez1, Carlos Paredes1, 2 y José Arenas3 1 Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Avenida Arenales 1256, Jesús María. Apartado 14-0434, Lima-14, Perú. 2 Laboratorio de Invertebrados Acuáticos, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Apartado 11-0058, Lima-11, Perú. 3 Laboratorio de Parasitología, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Ricardo Palma. Av. Benavides 5400, Surco. P.O. Box 18-131. Lima, Perú. Abstract: Peru is an ecologically diverse country, with 84 life zones in the Holdridge system and 18 ecological regions (including two marine). 1910 molluscan species have been recorded. The highest number corresponds to the sea: 570 gastropods, 370 bivalves, 36 cephalopods, 34 polyplacoforans, 3 monoplacophorans, 3 scaphopods and 2 aplacophorans (total 1018 species). The most diverse families are Veneridae (57spp.), Muricidae (47spp.), Collumbellidae (40 spp.) and Tellinidae (37 spp.). Biogeographically, 56 % of marine species are Panamic, 11 % Peruvian and the rest occurs in both provinces; 73 marine species are endemic to Peru. Land molluscs include 763 species, 2.54 % of the global estimate and 38 % of the South American esti- mate. The most biodiverse families are Bulimulidae with 424 spp., Clausiliidae with 75 spp. and Systrophiidae with 55 spp. In contrast, only 129 freshwater species have been reported, 35 endemics (mainly hydrobiids with 14 spp. The paper includes an overview of biogeography, ecology, use, history of research efforts and conser- vation; as well as indication of areas and species that are in greater need of study. -

(Approx) Mixed Micro Shells (22G Bags) Philippines € 10,00 £8,64 $11,69 Each 22G Bag Provides Hours of Fun; Some Interesting Foraminifera Also Included

Special Price £ US$ Family Genus, species Country Quality Size Remarks w/o Photo Date added Category characteristic (€) (approx) (approx) Mixed micro shells (22g bags) Philippines € 10,00 £8,64 $11,69 Each 22g bag provides hours of fun; some interesting Foraminifera also included. 17/06/21 Mixed micro shells Ischnochitonidae Callistochiton pulchrior Panama F+++ 89mm € 1,80 £1,55 $2,10 21/12/16 Polyplacophora Ischnochitonidae Chaetopleura lurida Panama F+++ 2022mm € 3,00 £2,59 $3,51 Hairy girdles, beautifully preserved. Web 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Ischnochitonidae Ischnochiton textilis South Africa F+++ 30mm+ € 4,00 £3,45 $4,68 30/04/21 Polyplacophora Ischnochitonidae Ischnochiton textilis South Africa F+++ 27.9mm € 2,80 £2,42 $3,27 30/04/21 Polyplacophora Ischnochitonidae Stenoplax limaciformis Panama F+++ 16mm+ € 6,50 £5,61 $7,60 Uncommon. 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Acanthopleura gemmata Philippines F+++ 25mm+ € 2,50 £2,16 $2,92 Hairy margins, beautifully preserved. 04/08/17 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Acanthopleura gemmata Australia F+++ 25mm+ € 2,60 £2,25 $3,04 02/06/18 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Acanthopleura granulata Panama F+++ 41mm+ € 4,00 £3,45 $4,68 West Indian 'fuzzy' chiton. Web 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Acanthopleura granulata Panama F+++ 32mm+ € 3,00 £2,59 $3,51 West Indian 'fuzzy' chiton. 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Chiton tuberculatus Panama F+++ 44mm+ € 5,00 £4,32 $5,85 Caribbean. 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Chiton tuberculatus Panama F++ 35mm € 2,50 £2,16 $2,92 Caribbean. 24/12/16 Polyplacophora Chitonidae Chiton tuberculatus Panama F+++ 29mm+ € 3,00 £2,59 $3,51 Caribbean. -

Mollusques Terrestres De L'archipel De La Guadeloupe, Petites Antilles

Mollusques terrestres de l’archipel de la Guadeloupe, Petites Antilles Rapport d’inventaire 2014-2015 Laurent CHARLES 2015 Mollusques terrestres de l’archipel de la Guadeloupe, Petites Antilles Rapport d’inventaire 2014-2015 Laurent CHARLES1 Ce travail a bénéficié du soutien financier de la Direction de l’Environnement de l’Aménagement et du Logement de la Guadeloupe (DEAL971, arrêté RN-2014-019). 1 Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle, 5 place Bardineau, F-33000 Bordeaux - [email protected] Citation : CHARLES L. 2015. Mollusques terrestres de l’archipel de la Guadeloupe, Petites Antilles. Rapport d’inventaire 2014-2015. DEAL Guadeloupe. 88 p., 11 pl. + annexes. Couverture : Helicina fasciata SOMMAIRE REMERCIEMENTS .................................................................................................................. 2 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 3 MATÉRIEL ET MÉTHODES .................................................................................................... 5 RÉSULTATS ............................................................................................................................ 9 Catalogue annoté des espèces ............................................................................................ 9 Espèces citées de manière erronée ................................................................................... 35 Diversité spécifique pour l’archipel .................................................................................... -

Land Snail Diversity in Brazil

2019 25 1-2 jan.-dez. July 20 2019 September 13 2019 Strombus 25(1-2), 10-20, 2019 www.conchasbrasil.org.br/strombus Copyright © 2019 Conquiliologistas do Brasil Land snail diversity in Brazil Rodrigo B. Salvador Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, New Zealand. E-mail: [email protected] Salvador R.B. (2019) Land snail diversity in Brazil. Strombus 25(1–2): 10–20. Abstract: Brazil is a megadiverse country for many (if not most) animal taxa, harboring a signifi- cant portion of Earth’s biodiversity. Still, the Brazilian land snail fauna is not that diverse at first sight, comprising around 700 native species. Most of these species were described by European and North American naturalists based on material obtained during 19th-century expeditions. Ear- ly 20th century malacologists, like Philadelphia-based Henry A. Pilsbry (1862–1957), also made remarkable contributions to the study of land snails in the country. From that point onwards, however, there was relatively little interest in Brazilian land snails until very recently. The last de- cade sparked a renewed enthusiasm in this branch of malacology, and over 50 new Brazilian spe- cies were revealed. An astounding portion of the known species (circa 45%) presently belongs to the superfamily Orthalicoidea, a group of mostly tree snails with typically large and colorful shells. It has thus been argued that the missing majority would be comprised of inconspicuous microgastropods that live in the undergrowth. In fact, several of the species discovered in the last decade belong to these “low-profile” groups and many come from scarcely studied regions or environments, such as caverns and islands. -

ZM82 615-650 Robinson.Indd

The land Mollusca of Dominica (Lesser Antilles), with notes on some enigmatic or rare species D.G. Robinson, A. Hovestadt, A. Fields & A.S.H. Breure Robinson, D.G., A. Hovestadt, A. Fields & A.S.H. Breure. The land Mollusca of Dominica, Lesser Antilles, with notes on some enigmatic or rare species. Zool. Med. Leiden 83 (13), 9.vii.2009: 615-650, fi gs 1-14, tables 1-2.― ISSN 0024-0672. D.G. Robinson, The Academy of Natural Sciences, 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, PA 19103, U.S.A. ([email protected]). A. Hovestadt, Dr. Abraham Kuyperlaan 22, NL-3818 JC Amersfoort, The Netherlands (ad.hovestadt@ xs4all.nl). A. Fields, Department of Biological and Chemical Sciences, University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Cam- pus, Barbados (angela.fi [email protected]). A.S.H. Breure, National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 9517, NL-2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands ([email protected]). Key words: Mollusca, Gastropoda, taxonomy, distribution, Dominica. An overview of the land-snail fauna of the Lesser Antillean island of Dominica is given, based on data from literature and four recent surveys. There are 42 taxa listed, of which the following species are recorded for the fi rst time from the island: Allopeas gracile (Hutt on, 1834), A. micra (d’Orbigny, 1835), Beckianum beckianum (L. Pfeiff er, 1846), Bulimulus diaphanus fraterculus (Potiez & Michaud, 1835), De- roceras laeve (Müller, 1774), Sarasinula marginata (Semper, 1885), Streptostele musaecola (Morelet, 1860) and Veronicella sloanii (Cuvier, 1817). The enigmatic Bulimulus stenogyroides Guppy, 1868 is now placed in the genus Naesiotus Albers, 1850. -

New Taxa of Land Snails from French Guiana

New taxa of land snails from French Guiana Olivier GARGOMINY Service du Patrimoine naturel, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, case postale 41, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05 (France) [email protected] Igor V. MURATOV KwaZulu-Natal Museum, P. Bag 9070, Pietermaritzburg 3200 (South Africa) School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Scottsville, 3206 (South Africa) [email protected] Gargominy O. & Muratov I. V. 2012. — New taxa of land snails from French Guiana. Zoosys tema 34 (4): 783-792. http://dx.doi.org/10.5252/z2012n4a7 ABSTRACT Three new species and a new genus of terrestrial gastropods are described from the Réserve naturelle des Nouragues in French Guiana. Cyclopedus anselini n. gen., n. sp. (forming new monotypical genus in the family Neocyclotidae Kobelt & Möllendorff, 1897) seems to be the smallest known cyclophoroid in the western hemisphere. The descriptions of the other two new species, KEYWORDS Pseudosubulina theoripkeni n. sp. and P. nouraguensis n. sp., from the family South America, Spiraxidae Baker, 1939, extend not only our knowledge of the geographical Neocyclotidae, distribution of Pseudosubulina Strebel & Pfeffer, 1882 (previously known with Spiraxidae, new genus, certainty from Mexico only) but also the diagnosis of this genus, which now new species. includes species with large penial stimulator and apertural dentition. RÉSUMÉ Nouveaux taxons d’escargots terrestres de Guyane française. Trois nouvelles espèces et un nouveau genre de gastéropodes terrestres sont décrits de la Réserve naturelle des Nouragues, en Guyane française. Cyclopedus anselini n. gen., n. sp., pour lequel le nouveau genre monotypique Cyclopedus n. gen. est établi, semble être le plus petit cyclophoroïde connu de l’hémisphère occidental. -

Mollusca (Geograpliische Verbreitung', Systematik Und Biologie) Für 1896-1000

© Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at Mollusca (geograpliische Verbreitung', Systematik und Biologie) für 1896-1000. Von Dr. \V. Kobelt. Verzeichniss der Publikationen, a) Jahrgang 1896. Adams, L. C. Interesting Kentish Forms. — In: J. Conch. Leeds vol. 8 p. 316—320. Aiicey, C. F. Descriptions of some new shells from the New Hebrides Archipelago. — In: Nautilus, vol. 10 p. 90 — 91. Andre, E. MoUusques d'Amboine. — In: Rev. Suisse Zool. vol. 4 p. 394—405. Baker, F. C. Preliminary Outline of a new Classification of the family Mtiricidae. — In: Bull. Chicago Ac. vol. 2 (1895) p. 109 —169. Baldwiu, D. D. Description of two new species AchatinelUdae from the Hawaiian Islands. — In: Nautilus, vol. 10 p. 31 —32. Beddome, C. E. Note on Cypraea angustata Gray, var. sub- carnea Ancey. — In: P. Linn. Soc. N. S. Wales vol. 21 p. 467—468. Benoist, E. Sur les Unio de la Gironde, et les especes pouvant fournir des perles. — In: Comptes Rendus Soc. Bordeaux 1896 p. 62—64. Bergli, R. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der Coniden. — In: Acta Ac. Leopold. Carol. v. 65 p. 67—214, mit 13 Taf. — (2). Beitrag zur Kenntniss der Gattungen Nanca und Onvstus. — In: Verh. zool.. -bot. Ges. Wien, v. 46 p. 212. Mit 2 Taf. — (3). Ueber die Gattung Doriopsüla. — In: Zool. Jahrb. Syst. V. 9 p. 454—458. — (4). Eolidiens d'Amboina. — In: Revue Suisse Zool. v. 4 p. 385—394. Avec pl. Blazka, F. Die Molluskenfauna der Elbe-Tümpel. — In: Zool. Anz. V. 19 p. 301— 307. © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at 11-2 Dr. -

Draft Recovery Plan for Five Species from American Sāmoa

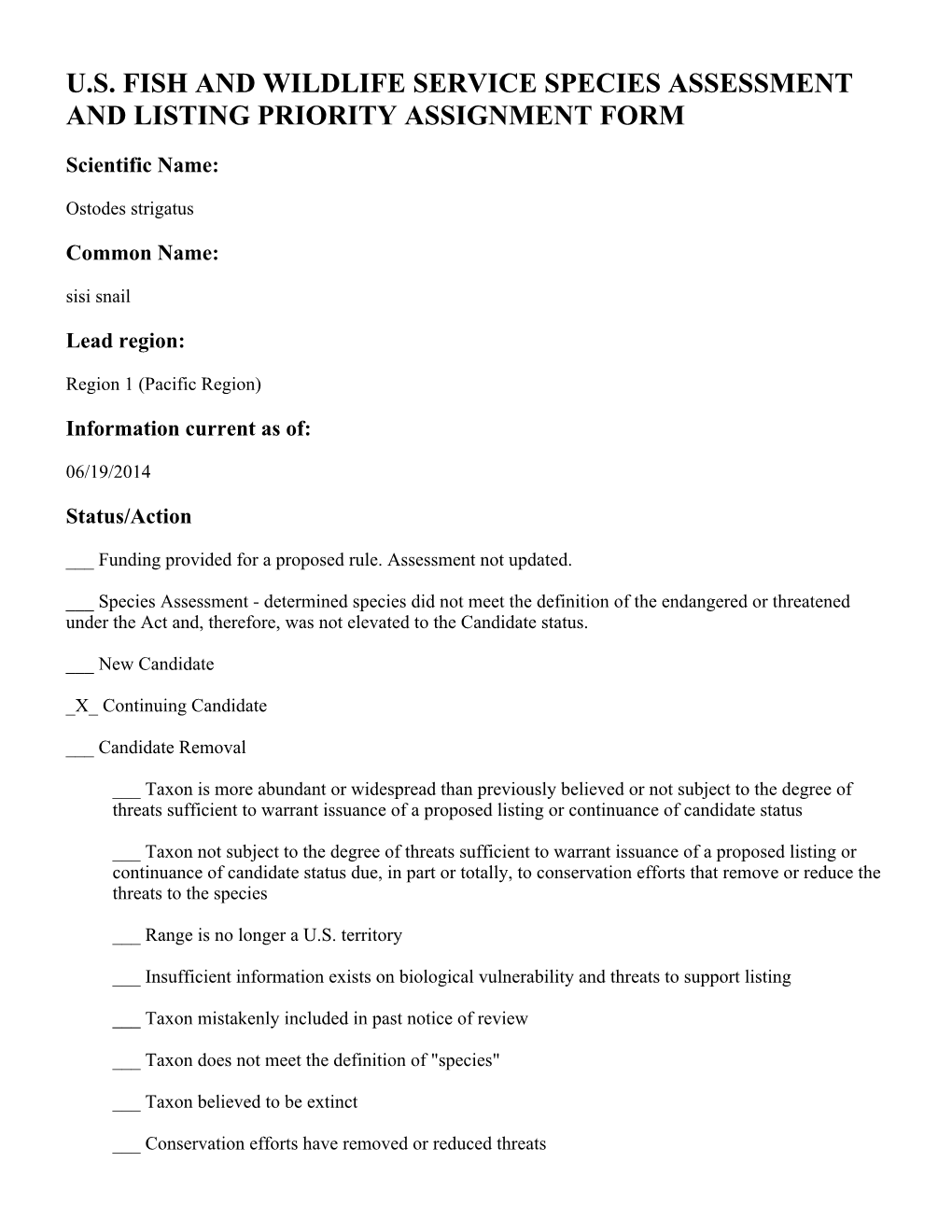

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Draft Recovery Plan for Five Species From American Sāmoa J. Malotaux R. Stirnemann Pe'ape'a Vai or Pacific Sheath-tailed BatBatBat Ma'oma'o Emballonura semicaudata semicaudata Gymnomyza samoensis Tu'aimeo or Friendly Ground-Dove J. Malotaux Gallicolumba stairi R. RundellRundellR. Rundell Eua zebrina R. Rundell Ostodes strigatus Draft Recovery Plan for Five Species from American Sāmoa Peʻapeʻa Vai or Pacific Sheath-tailed Bat, South Pacific Subspecies (Emballonura semicaudata semicaudata) Maʻomaʻo or Mao (Gymnomyza samoensis) Tuʻaimeo or Friendly Ground-Dove (Gallicolumba [=Alopecoenas] stairi) American Sāmoa Distinct Population Segment Eua zebrina Ostodes strigatus June 2020 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon Approved: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions needed to recover and/or protect listed species. We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), publish recovery plans, sometimes preparing them with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives of the recovery plan are accomplished, and funds made available, subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities with the same funds. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than our own. They represent our official position only after signed by the Director or Regional Director. Draft recovery plans are reviewed by the public and may be subject to additional peer review before the Service adopts them as final. Recovery objectives may be attained and funds expended contingent upon appropriations, priorities, and other budgetary constraints. -

THE BIOLOGY of TERRESTRIAL MOLLUSCS This Page Intentionally Left Blank the BIOLOGY of TERRESTRIAL MOLLUSCS

THE BIOLOGY OF TERRESTRIAL MOLLUSCS This Page Intentionally Left Blank THE BIOLOGY OF TERRESTRIAL MOLLUSCS Edited by G.M. Barker Landcare Research Hamilton New Zealand CABI Publishing CABI Publishing is a division of CAB International CABI Publishing CABI Publishing CAB International 10 E 40th Street Wallingford Suite 3203 Oxon OX10 8DE New York, NY 10016 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 Tel: +1 212 481 7018 Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 Fax: +1 212 686 7993 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] © CAB International 2001. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanically, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library, London, UK. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The biology of terrestrial molluscs/edited by G.M. Barker. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-85199-318-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mollusks. I. Barker, G.M. QL407 .B56 2001 594--dc21 00-065708 ISBN 0 85199 318 4 Typeset by AMA DataSet Ltd, UK. Printed and bound in the UK by Cromwell Press, Trowbridge. Contents Contents Contents Contributors vii Preface ix Acronyms xi 1 Gastropods on Land: Phylogeny, Diversity and Adaptive Morphology 1 G.M. Barker 2 Body Wall: Form and Function 147 D.L. Luchtel and I. Deyrup-Olsen 3 Sensory Organs and the Nervous System 179 R. Chase 4 Radular Structure and Function 213 U. Mackenstedt and K. Märkel 5 Structure and Function of the Digestive System in Stylommatophora 237 V.K. -

Gastropoda, Stylommatophora) of Palau

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 614: 27–49 (2016)Revision of Partulidae (Gastropoda, Stylommatophora) of Palau... 27 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.614.8807 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Revision of Partulidae (Gastropoda, Stylommatophora) of Palau, with description of a new genus for an unusual ground-dwelling species John Slapcinsky1, Fred Kraus2 1 Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611 USA 2 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA Corresponding author: John Slapcinsky ([email protected]) Academic editor: M. Schilthuizen | Received 11 April 2016 | Accepted 16 August 2016 | Published 1 September 2016 http://zoobank.org/48DF2601-BCB9-400B-B574-43B5B619E3B0 Citation: Slapcinsky J, Kraus F (2016) Revision of Partulidae (Gastropoda, Stylommatophora) of Palau, with description of a new genus for an unusual ground-dwelling species. ZooKeys 614: 27–49. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.614.8807 Abstract We describe a new stylommatophoran land snail of the family Partulidae from Palau. The new species has a combination of morphological and ecological characters that do not allow its placement in any existing partulid genus, so we describe a new genus for it. The new genus is characterized by a large (18–23 mm) obese-pupoid shell; smooth protoconch; teleoconch with weak and inconsistent, progressively stronger, striae; last half of body whorl not extending beyond the penultimate whorl; widely expanded and reflexed peristome; relatively long penis, with longitudinal pilasters that fuse apically into a fleshy ridge that divides the main chamber from a small apical chamber; and vas deferens entering and penial-retractor muscle at- taching at the apex of the penis. -

The Oldest Known Cyclophoroidean Land Snails (Caenogastropoda) from Asia Dinarzarde C

Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2017.1388298 The oldest known cyclophoroidean land snails (Caenogastropoda) from Asia Dinarzarde C. Raheema, Simon Schneiderb*, Madelaine Bohme€ c, Davit Vasiliyand,e and Jerome^ Prietof,g aLife Sciences Department, The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, UK; bCASP, 181A Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DH, UK; cSenckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoecology, University of Tubingen,€ Institute for Geoscience, Sigwartstrasse 10, 72076 Tubingen,€ Germany; dDepartment of Geosciences, University of Fribourg, Chemin du musee 6, 1700 Fribourg, Switzerland; eJURASSICA Museum, Route de Fontenais 21, 2900 Porrentruy, Switzerland; fBayerische Staatssammlung fur€ Pala€ontologie und Geologie; gDepartment of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Palaeontology & Geobiology, Ludwig-Maximilians- University Munich, Richard-Wagner-Strasse 10, 80333 Munchen,€ Germany (Received 4 April 2017; accepted 26 July 2017; published online 28 December 2017) The earliest Miocene (Aquitanian, 23–21 Ma) Hang Mon Formation at Hang Mon in Northern Vietnam has yielded a rich assemblage of terrestrial gastropods. Four species from this assemblage belong to the land caenogastropod superfamily Cyclophoroidea. Three of these are assigned to genera with Recent representatives in Southeast Asia and are described as new species: Cyclophorus hangmonensis Raheem & Schneider sp. nov. (Cyclophoridae: Cyclophorini), Alycaeus sonlaensis Raheem & Schneider sp. nov. (Cyclophoridae: Alycaeinae) and Tortulosa naggsi Raheem & Schneider sp. nov (Pupinidae: Pupinellinae). These fossil species represent the earliest records for their genera and are thus of great value for calibrating molecular phylogenies of the Cyclophoroidea. The fourth species is represented only by poorly preserved fragments and is retained in open nomenclature in the Cyclophoridae. While extant Cyclophoroidea have their greatest diversity in Tropical Asia, the oldest fossils described to date from the region are from the Late Pleistocene. -

Austrian Museum in Linz (Austria): History of Curatorial and Educational Activities Concerning Molluscs, Checklists and Profiles of Main Contributers

The mollusc collection at the Upper Austrian Museum in Linz (Austria): History of curatorial and educational activities concerning molluscs, checklists and profiles of main contributers E r n a A ESCHT & A g n e s B ISENBERGER Abstract: The Biology CentRe of the UppeR AuStRian MuSeum in Linz (OLML) haRbouRS collectionS of “diveRSe inveRtebRateS“ excluding inSectS fRom moRe than two centuRieS. ThiS cuRatoRShip exiStS Since 1992, Since 1998 tempoRaRily SuppoRted by a mol- luSc SpecialiSt. A hiStoRical SuRvey of acceSSion policy, muSeum’S RemiSeS, and cuRatoRS iS given StaRting fRom 1833. OuR publica- tion activitieS conceRning malacology, papeRS Related to the molluSc collection and expeRienceS on molluSc exhibitionS aRe Sum- maRiSed. The OLML holdS moRe than 105,000 RecoRded, viz laRgely well documented, about 3000 undeteRmined SeRieS and type mateRial of oveR 12,000 nominal molluSc taxa. ImpoRtant contRibuteRS to the pRedominantly gaStRopod collection aRe KaRl WeS- Sely (1861–1946), JoSef GanSlmayR (1872–1950), Stephan ZimmeRmann (1896–1980), WalteR Klemm (1898–1961), ERnSt Mikula (1900–1970), FRitz Seidl (1936–2001) and ChRiSta FRank (maRRied FellneR; *1951). Between 1941 and 1944 the Nazi Regime con- fiScated fouR monaSteRieS, i.e. St. FloRian, WilheRing, Schlägl and Vyšší BRod (HohenfuRth), including alSo molluScS, which have been tRanSfeRRed to Linz and lateR paRtially ReStituted. A contRact diScoveRed in the Abbey Schlägl StRongly SuggeStS that about 12,000 SpecimenS containS “duplicateS” (poSSibly SyntypeS) of SpecieS intRoduced in the 18th centuRy by Ignaz von BoRn and Johann CaRl MegeRle von Mühlfeld. On hand of many photogRaphS, paRticulaRly of taxa Sized within millimeteR RangeS and opeR- ated by the Stacking technique (including thoSe endangeRed in UppeR AuStRia), eigth tableS giving an oveRview on peRSonS involved in buidling the collection and liStS of countRieS and geneRa contained, thiS aRticle intendS to open the molluSc collec- tion of a pRovincial muSeum foR the inteRnational public.