Moving Ahead Into the Past: Historical Contexts in Recent Polish Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polish Cinema for Beginners

Polish Cinema for Beginners "Polish Cinema for Beginners" is a unique project - the first of its kind - both in Wroclaw and all of Poland, whose first edition took place in 2012 and was very popular with audiences. It is aimed directly at foreigners in order to present them with the masterpieces of Polish cinema. This will be shown, with English subtitles, on the big screen in Kino Nowe Horyzonty (New Horizons Cinema). In order to present the historical and artistic context of the films, each screening is introduced by a lecture in English, led by renowned experts - film scholars , journalists and scientists. Thanks to this, the project has not only entertainment, but also educational value, thus serving as a valuable course in Polish culture. Each screening is followed by an open discussion in which different cultural viewpoints are shared. After the discussion, viewers are cordially invited to a Polish Party in Wroclaw’s Gradient Club (at Solny Square). Our goal Through regular meetings and screenings of Polish films, we want to support the integration process of foreigners living in Wroclaw. We also want to show the history of Polish cinema and, more broadly, Polish culture, by placing the films in a wider socio- historical context. English-speaking Polish viewers will have the opportunity to see their native Polish films from a slightly different perspective, which - as shown by the reactions of foreigners during post-screening discussions – is sometimes surprising. What is more, we want to co-create the identity of Wroclaw as a city that stands out on the Polish map by offering equal- opportunity access to the cultural heritage of our country, by being an open city, and – especially in the context of its being chosen as European Capital of Culture 2016 – by offering an interesting and unique range of cultural and educational activities. -

4. UK Films for Sale at EFM 2019

13 Graves TEvolutionary Films Cast: Kevin Leslie, Morgan James, Jacob Anderton, Terri Dwyer, Diane Shorthouse +44 7957 306 990 Michael McKell [email protected] Genre: Horror Market Office: UK Film Centre Gropius 36 Director: John Langridge Home Office tel: +44 20 8215 3340 Status: Completed Synopsis: On the orders of their boss, two seasoned contract killers are marching their latest victim to the ‘mob graveyard’ they have used for several years. When he escapes leaving them no choice but to hunt him through the surrounding forest, they are soon hopelessly lost. As night falls and the shadows begin to lengthen, they uncover a dark and terrifying truth about the vast, sprawling woodland – and the hunters become the hunted as they find themselves stalked by an ancient supernatural force. 2:Hrs TReason8 Films Cast: Harry Jarvis, Ella-Rae Smith, Alhaji Fofana, Keith Allen Anna Krupnova Genre: Fantasy [email protected] Director: D James Newton Market Office: UK Film Centre Gropius 36 Status: Completed Home Office tel: +44 7914 621 232 Synopsis: When Tim, a 15yr old budding graffiti artist, and his two best friends Vic and Alf, bunk off from a school trip at the Natural History Museum, they stumble into a Press Conference being held by Lena Eidelhorn, a mad Scientist who is unveiling her latest invention, The Vitalitron. The Vitalitron is capable of predicting the time of death of any living creature and when Tim sneaks inside, he discovers he only has two hours left to live. Chased across London by tabloid journalists Tooley and Graves, Tim and his friends agree on a bucket list that will cram a lifetime into the next two hours. -

Painful Past, Fragile Future the Delicate Balance in the Western Balkans Jergović, Goldsworthy, Vučković, Reka, Sadiku Kolozova, Szczerek and Others

No 2(VII)/2013 Price 19 PLN (w tym 5% VAT) 10 EUR 12 USD 7 GBP ISSN: 2083-7372 quarterly April-June www.neweasterneurope.eu Painful Past, Fragile Future The delicate balance in the Western Balkans Jergović, Goldsworthy, Vučković, Reka, Sadiku Kolozova, Szczerek and others. Strange Bedfellows: A Question Ukraine’s oligarchs and the EU of Solidarity Paweï Kowal Zygmunt Bauman Books & Reviews: Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Mykola Riabchuk, Robert D. Kaplan and Jan Švankmajer Seversk: A New Direction A Siberian for Transnistria? Oasis Kamil Caïus Marcin Kalita Piotr Oleksy Azerbaijan ISSN 2083-7372 A Cause to Live For www.neweasterneurope.eu / 13 2(VII) Emin Milli Arzu Geybullayeva Nominated for the 2012 European Press Prize Dear Reader, In 1995, upon the declaration of the Dayton Peace Accords, which put an end to one of the bloodiest conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, the Bosnian War, US President, Bill Clinton, announced that leaders of the region had chosen “to give their children and their grandchildren the chance to lead a normal life”. Today, after nearly 20 years, the wars are over, in most areas peace has set in, and stability has been achieved. And yet, in our interview with Blerim Reka, he echoes Clinton’s words saying: “It is the duty of our generation to tell our grandchildren the successful story of the Balkans, different from the bloody Balkans one which we were told about.” This and many more observations made by the authors of this issue of New Eastern Europe piece together a complex picture of a region marred by a painful past and facing a hopeful, yet fragile future. -

Festival Centerpiece Films

50 Years! Since 1965, the Chicago International Film Festival has brought you thousands of groundbreaking, highly acclaimed and thought-provoking films from around the globe. In 2014, our mission remains the same: to bring Chicago the unique opportunity to see world- class cinema, from new discoveries to international prizewinners, and hear directly from the talented people who’ve brought them to us. This year is no different, with filmmakers from Scandinavia to Mexico and Hollywood to our backyard, joining us for what is Chicago’s most thrilling movie event of the year. And watch out for this year’s festival guests, including Oliver Stone, Isabelle Huppert, Michael Moore, Taylor Hackford, Denys Arcand, Liv Ullmann, Kathleen Turner, Margarethe von Trotta, Krzysztof Zanussi and many others you will be excited to discover. To all of our guests, past, present and future—we thank you for your continued support, excitement, and most importantly, your love for movies! Happy Anniversary to us! Michael Kutza, Founder & Artistic Director When OCTOBEr 9 – 23, 2014 Now in our 50th year, the Chicago International Film Festival is North America’s oldest What competitive international film festival. Where AMC RIVER EaST 21* (322 E. Illinois St.) *unless otherwise noted Easy access via public transportation! CTA Red Line: Grand Ave. station, walk five blocks east to the theater. CTA Buses: #29 (State St. to Navy Pier), #66 (Chicago Red Line to Navy Pier), #65 (Grand Red Line to Navy Pier). For CTA information, visit transitchicago.com or call 1-888-YOUR-CTA. Festival Parking: Discounted parking available at River East Center Self Park (lower level of AMC River East 21, 300 E. -

Andrzej Wajda Polski Film Dokumentalny

CMY CY MY CM K Y M C plakat_50_LAT_205x280_3mm.pdf 12016-01-1113:04:13 MAGAZYN FILMOWY 3 (55) / marzec 2016 Polski film dokumentalny film Polski NUMERU TEMAT okino walka wygrana Wajda Andrzej WYWIAD ISSN 2353-6357 WWW.SFP.ORG.PL 3 (55) / marzec 2016 nr 55 marzec 2016 Spis treści SFP/ZAPA 3 RYNEK FILMOWY Wydział Radia i Telewizji Uniwersytetu Śląskiego 46 POLSCYROZMOWA NUMERU Rozmowa z Rafałem Syską 50 Andrzej Wajda 4 Fundacja Wspierania Kultury Filmowej Cyrk Edison 52 Wytwórnia Scenariuszy 54 FILMOWCY Rozmowa z Simonem Stone’em 56 Film Factory w Sarajewie 58 MISTRZOWIE Krzysztof Kieślowski – projekty niezrealizowane 60 REFLEKSJE Audiowizualna historia kina 64 10 000 dni filmowej podróży 66 notacje Nie ma stolika 68 Fot. Kuba Kiljan/SFP Fot. Kuba MOJA (FILMOWA) MUZYKA Przemysław Gintrowski 69 TEMAT NUMERU Polski film dokumentalny12 SWOICH NIE ZNACIE archiwalneJoanna Klimkiewicz i Kamila Klimas-Przybysz 70 NIEWIARYGODNE PRZYGODY POLSKIEGO FILMU Maddalena 72 MIEJSCA Kino Narew 74 STUDIO MUNKA 76 Rys. Zbigniew Stanisławski Rys. PISF 78 WYDARZENIA KSIĄŻKI 80 Złote Taśmy 20 Nagrody PSC 21 DVD/CD 84 Dyplomaci w Kulturze 22 IN MEMORIAM 85 FESTIWALE W POLSCE Zoom-Zbliżenia 24 VARIA 87 Prowincjonalia 25 List DO redakcji 94 NAGRODY Honorowy Jańcio Wodnik 26 BOX OFFICE 95 WYSTAWY plakat_50_LAT_205x280_3mm.pdf 1 2016-01-11 13:04:13 Krzysztof Kieślowski. Ślady i pamięć 28 2016 marzec (55) / 3 POLSKIE PREMIERY ISSN 2353-6357 WWW.SFP.ORG.PL Kalendarz premier 30 2016 Rozmowa z Jerzym Zalewskim 32 marzec / ) 55 ( 3 Rozmowa z Maciejem Adamkiem 34 C M Y CM W PRODUKCJI 36 MY CY CMY K FESTIWALE ZA GRANICĄ Rotterdam 37 MAGAZYN FILMOWY Berlin 38 WYWIAD Andrzej Wajda Santiago de Chile 40 wygrana walka o kino TEMAT NUMERU Polski film dokumentalny POLSCY FILMOWCY NA ŚWIECIE 42 Na okładce: Andrzej Wajda Rys. -

Obce Ciało Press Kit En

FOREIGN BODY Directed by Krzysztof Zanussi CAST Angelo Riccardo Leonelli Kris Agnieszka Grochowska Kasia Agata Buzek Mira Weronika Rosati Father Sławomir Orzechowski Tamara Chulpan Khamatova Adam Bartek Żmuda Róża Ewa Krasnodębsk a Alessio Mattia Mor Angelo ’ mother Victoria Zinny Journalist Jacek Poniedziałek Hypnotist Janusz Chabior Mother Superior Stanisława Celińska Priest Maciej Robakiewicz Focolarino Tadeusz Bradecki Police officer Bartosz Obuchowicz CREW Director Krzysztof Zanussi Screenplay Krzysztof Zanussi Director of photography Piotr Niemyjski Costium e designer Katarzyna Lewińska Production designer Joanna Macha Producer Krzysztof Zanussi Executive producer Janusz Wąchała PRODUCTION DETAILS Genre drama Country Pol and / Italy / R ussia Production company TOR Film Production Co -produc tion companies Revolver Film In cooperation with TVCo National Program „Within The Family” WFDiF TVP With suport of TZMO S.A., Bella, Rostec Co -financed by Polish Film Institute Ministry of Culture and National Heritage TOR Film Production, e-mail: [email protected], phone: +48(22)8455303, www.tor.com.pl The Director about the film: “The film, which is intended to be a psychological drama, gives an account of a clash of corporate cynicism with youthful idealism. The perversity of the story comes from the fact that the one persecuted is a young man, an Italian, who is a genuine Christian. On the other side stands a row of liberated women who outperform the men in their cynicism and brutality of conduct. The result of the clash is inconclusive – idealism falters, although it has its Lord, while cynicism cracks, even though it’s far from being converted. The genealogy of the liberated woman catches a glimpse back to the past. -

Revisiting Andrzej Wajda's Korczak (1990)

Studia Filmoznawcze 39 Wroc³aw 2018 Marek Haltof Northern Michigan University THE CASUALTY OF JEWISH-POLISH POLEMICS: REVISITING ANDRZEJ WAJDA’S KORCZAK (1990) DOI: 10.19195/0860-116X.39.4 Emblematic of Wajda’s later career is Korczak (1990), one of the most important European pictures about the Holocaust. Steven Spielberg1 More interesting than the issue of Wajda’s alleged an- ti-Semitism is the question of Korczak’s martyrdom. East European Jews have suffered a posthumous violation for their supposed passivity in the face of the Nazi death machine. Why then should Korczak be exalted for leading his lambs to the slaughter? It is, I believe, because the fate of the Orphan’s Home hypostatizes the extremity of the Jewish situation — the innocence of the victims, their utter abandonment, their merciless fate. In the face of annihilation, Janusz Korczak’ tenderness is a terrifying reproach. He is the father who did not exist. J. Hoberman2 1 S. Spielberg, “Mr. Steven Spielberg’s Support Letter for Poland’s Andrzej Wajda,” Dialogue & Universalism 2000, no. 9–10, p. 15. 2 J. Hoberman, “Korczak,” Village Voice 1991, no. 6, p. 55. Studia Filmoznawcze, 39, 2018 © for this edition by CNS SF 39.indb 53 2018-07-04 15:37:47 54 | Marek Haltof Andrzej Wajda produced a number of films dealing with the Holocaust and Polish-Jewish relationships.3 His often proclaimed ambition had been to reconcile Poles and Jews.4 The scriptwriter of Korczak, Agnieszka Holland, explained that this was Wajda’s “obsession, the guilt.”5 Given the above, it should come as no surprise that he chose the story of Korczak as his first film after the 1989 return of democracy in Poland. -

Agata Buzek | Biography

AGATA BUZEK | BIOGRAPHY Agata Buzek was born in Gliwice, Poland and trained at the Theatre Academy in Warsaw. Since her film debut in LA BALLATA DEI LAVAVETRI (Peter del Monte, Italy, 1998), she has worked in many international co- productions including LIBRE CIRCULATION (Jean-Marc Moutout, 2002), VALERIE (Birgit Möller, 2007) as well as in films with renowned directors including: THE HIDDEN TREASURE (Skarby Ukryte, Krysztof Zanussi, 2000); THE REVENGE (Zemsta, Andrzej Wajda, 2002) for which Agata was nominated as Best Supporting Actress at the Polish Film Awards; NIGHTWATCHING (Peter Greenaway, 2007) and WITHIN THE WHILRWIND (Marleen Gorris, 2008). For her performance in Borys Lankosz’s REVERSE (Poland’s national submission for the 2010 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film), Agata received a Best Actress award at the 34th Polish Film Festival in Gdynia and she was named as Berlinale Shooting Star 2010 for Poland. In 2012 Agata was co-starring alongside Jason Statham in HUMMINGBIRD. IMDb Pro and IMDb www.spiel-kind.com | 28.09.2021 Agata Buzek | CV FEATURE | TELEVISION 2021 | Das Netz - Prometheus (AT) | TV series | Director: Andreas Prochaska, Daniel Prochaska | MR Film, Sommerhaus Serien, Red Bull Media House, Beta Film | ARD Degeto, Servus TV 2020 | Paradis Sale | feature film | Director: Bertrand Mandico | Ecce Films 2019 | Tak ma byc | feature film | Director: Lukasz Grzegorzek | Koskino Natalia Grzegorzek 2019 | The Pit | feature film | Director: Dace Puce | Marana Production, Inland Film Company 2019 | Dune Dreams | feature -

European Journal of American Studies, 13-3 | 2018 Dances with Westerns in Poland’S Borderlands 2

European journal of American studies 13-3 | 2018 Special Issue: America to Poland: Cultural Transfers and Adaptations Dances with Westerns in Poland’s Borderlands Piotr Skurowski Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/13595 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.13595 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Piotr Skurowski, “Dances with Westerns in Poland’s Borderlands ”, European journal of American studies [Online], 13-3 | 2018, Online since 07 January 2019, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/ejas/13595 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.13595 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License Dances with Westerns in Poland’s Borderlands 1 Dances with Westerns in Poland’s Borderlands Piotr Skurowski 1 Parallel to other European countries, the American West has always stirred a great fascination in the Polish public. An important part of the Polish context which seems responsible for that fascination was the role played in Polish history by the eastern borderlands (Kresy) whose place in the Polish imaginary seems to parallel, in some important aspects, the mythmaking role played by the Wild West in America. The mythic appeal of the Kresy owes a lot to one of the key Polish mythmakers, the novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz whose famous Trilogy strongly defined the Polish imaginary concerning the history of the Kresy for generations to come. In Sienkiewicz’s mythic vision, the Ukrainian steppes constituted a scenic backdrop for a heroic struggle of the righteous and chivalric Poles against the invasions of barbarian hordes from the East, including the Cossacks, Turks and Tartars. -

The Innocents

presents THE INNOCENTS A film by Anne Fontaine 115 min | France/Poland | 2016 | PG-13 | 1.85 In French and Polish with English subtitles Official Website: http://www.musicboxfilms.com/innocents Press Materials: http://www.musicboxfilms.com/innocents-press New York/National Press Contacts: Sophie Gluck & Associates Sophie Gluck: [email protected] | 212-595-2432 Aimee Morris: [email protected] | 212-595-2432 Los Angeles Press Contacts: Marina Bailey Film Publicity Marina Bailey: [email protected] | 323-962-7511 Sara Tehrani: [email protected] | 323-962-7511 Music Box Films Contacts Marketing & Publicity Yasmine Garcia | [email protected] | 312-508-5362 Theatrical Booking Brian Andreotti | [email protected] | 312-508-5361 Exhibition Materials Lindsey Jacobs | [email protected] | 312-508-5365 FESTIVALS AND AWARDS Official Selection – Sundance Film Festival Official Selection – COLCOA Film Festival Official Selection – San Francisco Int’l Film Festival Official Selection – Minneapolis St. Paul Int’l Film Festival Official Selection – Newport Beach Film Festival SYNOPSIS Warsaw, December 1945: the second World War is finally over and French Red Cross doctor Mathilde (Lou de Laage) is treating the last of the French survivors of the German camps. When a panicked Benedictine nun appears at the clinic begging Mathilde to follow her back to the convent, what she finds there is shocking: a holy sister about to give birth and several more in advanced stages of pregnancy. A non-believer, Mathilde enters the sisters’ fiercely private world, dictated by the rituals of their order and the strict Rev. Mother (Agata Kulesza, Ida). Fearing the shame of exposure, the hostility of the occupying Soviet troops and local Polish communists and while facing an unprecedented crisis of faith, the nuns increasingly turn to Mathilde as their beliefs and traditions clash with harsh realities. -

“The Eccentrics”

“THE ECCENTRICS” “ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET” A film by JANUSZ MAJEWSKI SYNOPSIS “Eccentrics” is an incredible story of a jazzman Fabian(Maciej Stuhr) who comes back to Poland from England at the end of the 1950ies. With a group of eccentric musicians he starts a swing big-band. Modesta (Natalia Rybicka) becomes the star of the band and they become very successful. The musician quickly falls head over hills in love with the femme fatale singer. They soon start an affair. As king and queen of swing they start touring Poland and their life takes a colourful turn. Will their feelings last? ABOUT THE FILM End of 1950ies. Fabian (Maciej Stuhr), a war immigrant and jazzman decides to come back to Poland from England. He played the trombone on a Polish transatlantic ship before the war. He comes to see his sister Wanda (Sonia Bohosiewicz) in Ciechocinek, in order to play swing again. What he doesn’t know though is that is bound to find love too. From both professional and amateur musicians he forms a swing big band. They are a group of very eccentric people whose mutual meeting brings out many funny and unexpected situations. We have a music- hater piano- tuner named Zuppe who sees a homosexual in every musician ( Awarded for Best Actor at the Gdynia Film Festival - Wojciech Pszoniak), a distinguished doctor Mr Vogt (Jerzy Schejbal), a clarinet amateur (Adam Ferency), a police officer who played the trumpet before the war (Wiktor Zborowski) and a group of young beatniks (Wojtek Mazolewski and his musicians). -

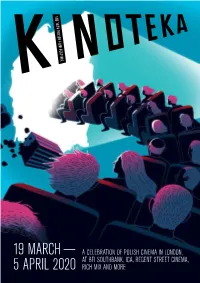

Kinoteka2020 Guide-Compressed.Pdf

Welcome to Kinoteka 18! 1 kinoteka.org.u k Welcome to Kinoteka 18! Welcome to Kinoteka 18! 1 CONTENTS WELCOME TO KINOTEKA 18! Welcome to KINOTEKA 18! ................................................................ 1 As we enter a new decade, Polish film documentaries with a trio of recent films, continues to go from strength to strength. spanning topics such as loneliness, Japanese While Agnieszka Holland, that tireless voice students’ struggles with learning the Polish SCREENINGS & EVENTS from the old guard of Polish film-making, language, and romantic intimacy among the Opening Night Gala ....................................................................... 4 continues to channel her vision with Mr. tragedy of the Warsaw Ghetto. New Polish Cinema ........................................................................ 6 Jones, a number of newer talents have broken We continue to bring you the best in through – most notably, screenwriter Mateusz exclusive cinematic experiences with a Documentaries ............................................................................ 12 Pacewicz and actor Bartosz Bielenia in Corpus series of interactive events and showcases Focus: Richard Boleslawski ............................................................... 16 Christi, Poland’s short-listed entry for this encompassing the breadth of cinema history. Family Event .............................................................................. 18 year’s Academy Awards. At the 18th Kinoteka The Cinema Museum focuses on the early Tadeusz Kantor