The CRTC's Enforcement of Canada's Broadcast Legislation: 'Concern', 'Serious Concern' and 'Grave Concern'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"'Ce';;) .. ·· LES GARANTS D'achevement 'Toronto, John Ross, (416) 466-2760 (\\,\'0" ••• ' Pour Series De Television, Longs Metrages Telex: 055-62276 {'

CINEMA CAN •A D A BY JIM LEVESQUE George Wright, Helene Fournier, Philip he following is a list of current projects being produced in ATLANTIS p. Paul Saltzman lOp. p . Harold JacksDa.. (416)462-0246 THE WAY WE ARE TIchenor pelt. prod p. Paul Quigley Canada. Only TV series and films over one hour are An anrhok>gy series which showcases p. man. Gordon Mark eXK. 11 . con •. TNI! TWILIQNT ZON. ....KO FILMS LTD. a collection of regional dr8mas Ann MacNaughton d . Rex Bromfield, included. Projects are separated into four categories: On london Films snd AtlantiS Films are (416) 960.3228 T produced in Vancouver, Edmonton, Ken Jubenvill. Allan King, Alan collaborating with CBS BroAdcast THE LAIT fRONTll!R Location, Pre-production, Projects in Negotiation, and In the Can. Calgary. Winnipeg, Regina, Toronto, Simmonds, BradTurnerlI18. d. T. W. Intemational on 30 new 1/2h scl·fi The third season of tne 70 x 1/2h TV Ottawa, Montreal, Halifax, and St. PaacO(;~e, Mick MacKay d.o. p. Bob While films in the project stage are subject to change, only those episodes of the classic series series about the sea. This JOhn·s.ex8C.p. Robert Alten pub. Ennis loc. man. George Horie calt.. Shooting through '88 on location in ad\lenture/documentary series Is in active pre-production at the time of publication - those which Susan Procter wrtterl Peter Roberts, Trish Robinson extral. Annette T oronlo. Delivery at the shows is s1ated co-produced by Mako Films ltd. and Jona1han Campbell, David Pe1ersen, McCafferey art d. Jill Scott pub. -

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2021-169

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2021-169 PDF version Reference: Part 1 application posted on 17 November 2020 Ottawa, 11 May 2021 Byrnes Communications Inc. Fort Erie, Ontario Public record for this application: 2020-0541-2 CFLZ-FM Fort Erie – Licence amendment The Commission denies the application by Byrnes Communications Inc. to amend the broadcasting licence for the English-language commercial radio station CFLZ-FM Fort Erie, Ontario, by deleting its condition of licence related to news. This condition of licence states that, during each broadcast week, the licensee shall broadcast, at a minimum, three hours of news programming. Of this amount, a minimum of 30% (54 minutes) each week shall be devoted to local news of direct and particular relevance to Fort Erie and the Niagara region. Application 1. The Commission has the authority, pursuant to section 9(1) of the Broadcasting Act (the Act), to issue and renew licences for such terms not exceeding seven years and subject to such conditions related to the circumstances of the licensee as it deems appropriate for the implementation of the broadcasting policy set out in section 3(1) of the Act, as well as to amend those conditions on application of the licensee. 2. Byrnes Communications Inc. (Byrnes) filed an application to amend the broadcasting licence for the English-language commercial radio programming undertaking CFLZ-FM Fort Erie, Ontario. Specifically, Byrnes proposed to delete condition of licence number 3 set out in the appendix to Broadcasting Decision 2018-12, which reads as follows: During each broadcast week, the licensee shall broadcast, at a minimum, three hours of news programming. -

Channel Line-Up VIP Digital Cable (Markham)

Channel Line-Up VIP Digital Cable (Markham) Here are the channels included in your package CH# INCL CH# INCL CH# INCL Your World This Week 1 Sportsnet 360 44 DIY Network 89 TV Ontario (TVO - CICA) 2 OLN 45 Disney Junior 92 Global Toronto (CIII) 3 Turner Classic Movies 46 Disney Channel 93 OMNI.1 4 TELETOON (East) 47 Free Preview Channel 1 94 TV Listings 5 Family Channel (East) 48 FX 95 CBC Toronto (CBLT) 6 Peachtree TV 49 NBA TV Canada 96 Citytv Toronto 7 CTV Comedy Channel (East) 50 Leafs Nation Network 97 CTV Toronto (CTVTO) 8 FX 51 TSN2 98 YES TV 9 Food Network 52 Sportsnet ONE 99 CHCH 11 ABC Spark 53 Rogers On Demand 100 ICI Radio-Canada Télé (TOR) 12 History 54 TVA Montreal (CFTM) 101 TFO (CHLF) 13 CTV Sci-Fi Channel 55 ICI RDI 102 OMNI.2 14 MTV 56 TV5 103 FX 15 BET (Black Entertainment 57 CPAC English (& CPAC French- 104 CBS Bufalo (WIVB) 16 DTOUR 58 Ontario Legislature 105 Sportsnet ONE 17 Your World This Week 59 Makeful 106 ABC Bufalo (WKBW) 18 VisionTV 60 A.Side 107 Today's Shopping Choice 19 PBS Bufalo (WNED) 61 CTV Toronto (CTVTO) 108 CTV Two Toronto 20 CTV News Channel 62 CTV Kitchener/London (CTVSO) 109 FOX Bufalo (WUTV) 21 Free Preview Channel 1 63 CTV Winnipeg (CTVWN) 110 The Weather Network (Richmond) 22 CTV Life Channel 64 CTV Calgary (CTVCA) 111 CBC News Network/AMI-audio 23 Treehouse 65 CTV Vancouver (CTVBC) 112 CP24 24 BNN Bloomberg 66 CTV Two Atlantic 113 YTV (East) 25 Nat Geo Wild 67 CTV Atlantic Halifax (CJCH) 114 TSN4 26 Family Jr. -

AGREEMENT Between CTV Television, Division of Bell Media

AGREEMENT between CTV Television, Division of Bell Media Inc. TORONTO, ONTARIO - and - COMMUNICATIONS, ENERGY AND PAPERWORKERS UNION OF CANADA (LOCAL 720-M) January 1, 2012 To December 31, 2017 Table of Contents Article Page 1 Intent ................................................................. 1 Definitions 2.1 Employee .......................................................... 2 2.2 Bargaining Unit ................................................. 2 2.3 Employee Categories ........................................ 3 3 Management Rights .......................................... 5 Union Rights 4.1 Membership and Dues ...................................... 6 4.2 Notices to Union ............................................... 8 4.3 Union Access to Premises ................................. 8 4.4 Union Use of Bulletin Boards ........................... 9 4.5 Leave For Union Activities ............................... 9 4.6 Non-Discrimination .......................................... 11 5 No Strike, Lockouts or Strike-breaking ............ 11 6 Grievance Procedure ......................................... 12 7 Reports on Performance .................................... 15 Table of Contents Article Page Seniority Rights 8.1 Company Seniority ........................................... 17 8.2 Unit Seniority .................................................... 17 8.3 Promotion and Transfers ................................... 17 8.4 Dismissal, Demotion and Suspension 18 8.5 Layoffs ............................................................. -

13 January 2014

20 November 2014 John Traversy Secretary General CRTC Ottawa, ON K1A 0N2 Dear Mr. Secretary General, Re: Application 2014‐0793‐2, Broadcasting Notices of Consultation 2014‐541 and 2014‐541‐1 (Ottawa, 21 October 2014 and 27 October 2014) 1 The Forum for Research and Policy in Communications (FRPC) is a non‐profit and non‐partisan organization established to undertake research and policy analysis about communications, including broadcasting. The Forum supports a strong Canadian broadcasting system and regulation that serves the public interest. 2 FRPC is pleased to participate in the process initiated by Broadcasting Notice of Consultation 2014‐541, to address the application for a network licence submitted by Rogers Sports Inc. (RSI), the licensee of the Category C specialty service known as Sportsnet. The Forum opposes RSI’s application as it is current set eout, on th grounds of insufficient evidence: RSI has presented too little information to enable the CRTC to know what it would be licensing, and the information that RSI has presented does not establish that its network licence will serve the public interest by achieving Parliament’s objects for the broadcasting system, or by improving or strengthening that system. 3 The Forum wishes to be considered as an intervener in this proceeding, and respectfully requests the opportunity to appear at the hearing scheduled for 8 January 2015 to set out its views in greater detail and to respond to the applicant. Our contact information is provided at the end of our intervention. I The application by Rogers Sports Inc. 4 This section sets out the facts and arguments being made by RSI in support of the application that is asking the CRTC to approve. -

CTN Reaches Your Consumer

MAJOR MARKET AFFILIATES TORONTO CFMJ (AM640) 640 AM News/Talk CHBM (Boom) 97.3 FM Classic Hits CIRR (PROUD FM) * 103.9 FM AC CFMZ (Classical) 96.3 FM Classical CIDC (Z103) 103.5 FM Hits CJRT (Jazz-FM) 91.1 FM Jazz CFNY (The Edge) 102.1 FM Alt Rock CILQ (Q107) 107.1 FM Classic Rock CKDX (The Jewel) 88.5 FM Lite Hits CFRB (NewsTalk 1010) 1010 AM Today'sNews/Talk Best CHUM AM(TSN Radio) 1050 AM Sports CKFM (Virgin) 99.9 FM Top 40 CHUM (CHUM FM) 104.5 FM Music CFXJ (The Move) 93.5 FM Rhythmic AC CHFI (Perfect Music Mix) 98.1 FM AC CJCL (Sportsnet590) 590 AM Sports CFTR (680News) 680 AM News MONTREAL (French) CHMP 98.5 FM News/Talk CJPX (Radio Classique)* 99.5 FM Classical CKMF (NRJ) 94.3 FM Top 40 CITE (Rouge FM) 107.3 FM AC CKAC (Radio Circulation) 730 AM All Traffic CKOI 96.9 FM Top 40 MONTREAL (English) CKBE (The Beat) 92.5 FM AC CJAD 800 AM News/Talk CJFM (Virgin) 95.9 FM Hot AC CHOM 97.7 FM Classic Rock CKGM (TSN Radio) 690 AM Sports VANCOUVER CFMI (Rock 101) 101 FM Classic Rock CJJR (JR FM) 93.7 FM New Country CKWX (News 1130) 1130 AM All News CFOX (The Fox) 99.3 FM New Rock CJAX (Jack FM) 96.9 FM Hits CKZZ (Z95.3) 95.3 FM Hot AC CHMJ 730 AM Traffic CKNW (News Talk) 980 AM News/Talk CHLG (The Breeze) 104.3 FM Relaxing Favourites CISL (Sportsnet 650) 650 AM Sports CKPK (The Peak) 102.7 FM Rock CKST (TSN Radio) 1040 AM Sports CFBT (Virgin) 94.5 FM Hit Music CHQM (QMFM) 103.5 FM Soft Rock CFTE (Bloomberg Radio) 1410 AM Business News FRASER VALLEY CHWK (The Drive)* 89.5 FM Classic Hits CKQC 107.1 FM Country (A) CKSR (Star FM) 98.3 FM Rock -

Broadcasting Notice of Consultation CRTC 2013-325

Broadcasting Notice of Consultation CRTC 2013-325 PDF version Ottawa, 5 July 2013 Notice of applications received Various locations Renewal of the broadcasting licences for certain religious and commercial radio stations – Licensees in apparent repeated non-compliance Deadline for submission of interventions/comments/answers: 9 August 2013 [Submit an intervention/comment/answer or view related documents] The Commission announces that it has received applications to renew the broadcasting licences for certain religious and commercial radio programming undertakings, which expire 31 August 2013. The licensees propose to operate their undertakings under the same terms and conditions as those set out in the current licences, with the exception of Canadian talent development (CTD) requirements, which have been replaced by the Canadian content development (CCD) requirements set out in section 15 of the Radio Regulations, 1986 (the Regulations). In addition, the licensees will be required to adhere to the conditions set out in Conditions of licence for commercial AM and FM radio stations, Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2009-62, 11 February 2009. In each case, the Commission has examined the licensee’s compliance with requirements regarding CTD, CCD and the filing of annual returns, as set out by condition of licence and in section 9(2) of the Regulations. In certain cases, the Commission monitored logger tapes and music lists to determine the licensee’s compliance with requirements regarding the broadcast of Canadian musical selections and French-language vocal music, where applicable. In the list below, stations identified with an asterisk (*) have been monitored by the Commission. The monitoring report has been placed on each licensee’s public examination file. -

FACTOR 2006-2007 Annual Report

THE FOUNDATION ASSISTING CANADIAN TALENT ON RECORDINGS. 2006 - 2007 ANNUAL REPORT The Foundation Assisting Canadian Talent on Recordings. factor, The Foundation Assisting Canadian Talent on Recordings, was founded in 1982 by chum Limited, Moffat Communications and Rogers Broadcasting Limited; in conjunction with the Canadian Independent Record Producers Association (cirpa) and the Canadian Music Publishers Association (cmpa). Standard Broadcasting merged its Canadian Talent Library (ctl) development fund with factor’s in 1985. As a private non-profit organization, factor is dedicated to providing assistance toward the growth and development of the Canadian independent recording industry. The foundation administers the voluntary contributions from sponsoring radio broadcasters as well as two components of the Department of Canadian Heritage’s Canada Music Fund which support the Canadian music industry. factor has been managing federal funds since the inception of the Sound Recording Development Program in 1986 (now known as the Canada Music Fund). Support is provided through various programs which all aid in the development of the industry. The funds assist Canadian recording artists and songwriters in having their material produced, their videos created and support for domestic and international touring and showcasing opportunities as well as providing support for Canadian record labels, distributors, recording studios, video production companies, producers, engineers, directors– all those facets of the infrastructure which must be in place in order for artists and Canadian labels to progress into the international arena. factor started out with an annual budget of $200,000 and is currently providing in excess of $14 million annually to support the Canadian music industry. Canada has an abundance of talent competing nationally and internationally and The Department of Canadian Heritage and factor’s private radio broadcaster sponsors can be very proud that through their generous contributions, they have made a difference in the careers of so many success stories. -

A Night at the Garden (S): a History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship

A Night at the Garden(s): A History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship in the 1920s and 1930s by Russell David Field A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Russell David Field 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2021-297

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2021-297 PDF version Ottawa, 30 August 2021 Various licensees Across Canada Various commercial radio programming undertakings – Administrative renewals 1. The Commission renews the broadcasting licences for the commercial radio programming undertakings set out in the appendix to this decision from 1 September 2022 to 31 August 2023, subject to the terms and conditions in effect under the current licences. 2. This decision does not dispose of any issues that may arise with respect to the renewal of these licences, including any non-compliance issues. Secretary General This decision is to be appended to each licence. Appendix to Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2021-297 Various commercial radio programming undertakings for which the broadcasting licences are administratively renewed until 31 August 2023 Province/Territory Licensee Call sign and location British Columbia Bell Media Inc. CHOR-FM Summerland CKGR-FM Golden and its transmitter CKIR Invermere Bell Media Regional CFBT-FM Vancouver Radio Partnership CHMZ-FM Radio Ltd. CHMZ-FM Tofino CIMM-FM Radio Ltd. CIMM-FM Ucluelet Corus Radio Inc. CKNW New Westminster Four Senses Entertainment CKEE-FM Whistler Inc. Jim Pattison Broadcast CHDR-FM Cranbrook Group Limited Partnership CHWF-FM Nanaimo CHWK-FM Chilliwack CIBH-FM Parksville CJDR-FM Fernie and its transmitter CJDR-FM-1 Sparwood CJIB-FM Vernon and its transmitter CKIZ-FM-1 Enderby CKBZ-FM Kamloops and its transmitters CKBZ-FM-1 Pritchard, CKBZ-FM-2 Chase, CKBZ-FM-3 Merritt, CKBZ-FM-4 Clearwater and CKBZ-FM-5 Sun Peaks Resort CKPK-FM Vancouver Kenneth Collin Brown CHLW-FM Barriere Merritt Broadcasting Ltd. -

The Rise and Decline of the Cooperative Commonwealth

THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE COOPERATIVE COMMONWEALTH FEDERATION IN ONTARIO AND QUEBEC DURING WORLD WAR II, 1939 – 1945 By Charles A. Deshaies B. A. State University of New York at Potsdam, 1987 M. A. State University of New York at Empire State, 2005 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine December 2019 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Nathan Godfried, Professor of History Stephen Miller, Professor of History Howard Cody, Professor Emeritus of Political Science Copyright 2019 Charles A. Deshaies All Rights Reserved ii THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE COOPERATIVE COMMONWEALTH FEDERATION IN ONTARIO AND QUEBEC DURING WORLD WAR II, 1939 – 1945 By Charles A. Deshaies Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Scott See and Dr. Jacques Ferland An Abstract of the Thesis Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) December 2019 The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) was one of the most influential political parties in Canadian history. Without doubt, from a social welfare perspective, the CCF helped build and develop an extensive social welfare system across Canada. It has been justly credited with being one of the major influences over Canadian social welfare policy during the critical years following the Great Depression. This was especially true of the period of the Second World War when the federal Liberal government of Mackenzie King adroitly borrowed CCF policy planks to remove the harsh edges of capitalism and put Canada on the path to a modern Welfare State. -

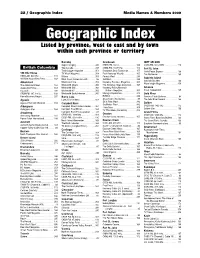

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance.