MONIQUE T. LAFONTAINE Graduate Programme in Law North York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"'Ce';;) .. ·· LES GARANTS D'achevement 'Toronto, John Ross, (416) 466-2760 (\\,\'0" ••• ' Pour Series De Television, Longs Metrages Telex: 055-62276 {'

CINEMA CAN •A D A BY JIM LEVESQUE George Wright, Helene Fournier, Philip he following is a list of current projects being produced in ATLANTIS p. Paul Saltzman lOp. p . Harold JacksDa.. (416)462-0246 THE WAY WE ARE TIchenor pelt. prod p. Paul Quigley Canada. Only TV series and films over one hour are An anrhok>gy series which showcases p. man. Gordon Mark eXK. 11 . con •. TNI! TWILIQNT ZON. ....KO FILMS LTD. a collection of regional dr8mas Ann MacNaughton d . Rex Bromfield, included. Projects are separated into four categories: On london Films snd AtlantiS Films are (416) 960.3228 T produced in Vancouver, Edmonton, Ken Jubenvill. Allan King, Alan collaborating with CBS BroAdcast THE LAIT fRONTll!R Location, Pre-production, Projects in Negotiation, and In the Can. Calgary. Winnipeg, Regina, Toronto, Simmonds, BradTurnerlI18. d. T. W. Intemational on 30 new 1/2h scl·fi The third season of tne 70 x 1/2h TV Ottawa, Montreal, Halifax, and St. PaacO(;~e, Mick MacKay d.o. p. Bob While films in the project stage are subject to change, only those episodes of the classic series series about the sea. This JOhn·s.ex8C.p. Robert Alten pub. Ennis loc. man. George Horie calt.. Shooting through '88 on location in ad\lenture/documentary series Is in active pre-production at the time of publication - those which Susan Procter wrtterl Peter Roberts, Trish Robinson extral. Annette T oronlo. Delivery at the shows is s1ated co-produced by Mako Films ltd. and Jona1han Campbell, David Pe1ersen, McCafferey art d. Jill Scott pub. -

AGREEMENT Between CTV Television, Division of Bell Media

AGREEMENT between CTV Television, Division of Bell Media Inc. TORONTO, ONTARIO - and - COMMUNICATIONS, ENERGY AND PAPERWORKERS UNION OF CANADA (LOCAL 720-M) January 1, 2012 To December 31, 2017 Table of Contents Article Page 1 Intent ................................................................. 1 Definitions 2.1 Employee .......................................................... 2 2.2 Bargaining Unit ................................................. 2 2.3 Employee Categories ........................................ 3 3 Management Rights .......................................... 5 Union Rights 4.1 Membership and Dues ...................................... 6 4.2 Notices to Union ............................................... 8 4.3 Union Access to Premises ................................. 8 4.4 Union Use of Bulletin Boards ........................... 9 4.5 Leave For Union Activities ............................... 9 4.6 Non-Discrimination .......................................... 11 5 No Strike, Lockouts or Strike-breaking ............ 11 6 Grievance Procedure ......................................... 12 7 Reports on Performance .................................... 15 Table of Contents Article Page Seniority Rights 8.1 Company Seniority ........................................... 17 8.2 Unit Seniority .................................................... 17 8.3 Promotion and Transfers ................................... 17 8.4 Dismissal, Demotion and Suspension 18 8.5 Layoffs ............................................................. -

13 January 2014

20 November 2014 John Traversy Secretary General CRTC Ottawa, ON K1A 0N2 Dear Mr. Secretary General, Re: Application 2014‐0793‐2, Broadcasting Notices of Consultation 2014‐541 and 2014‐541‐1 (Ottawa, 21 October 2014 and 27 October 2014) 1 The Forum for Research and Policy in Communications (FRPC) is a non‐profit and non‐partisan organization established to undertake research and policy analysis about communications, including broadcasting. The Forum supports a strong Canadian broadcasting system and regulation that serves the public interest. 2 FRPC is pleased to participate in the process initiated by Broadcasting Notice of Consultation 2014‐541, to address the application for a network licence submitted by Rogers Sports Inc. (RSI), the licensee of the Category C specialty service known as Sportsnet. The Forum opposes RSI’s application as it is current set eout, on th grounds of insufficient evidence: RSI has presented too little information to enable the CRTC to know what it would be licensing, and the information that RSI has presented does not establish that its network licence will serve the public interest by achieving Parliament’s objects for the broadcasting system, or by improving or strengthening that system. 3 The Forum wishes to be considered as an intervener in this proceeding, and respectfully requests the opportunity to appear at the hearing scheduled for 8 January 2015 to set out its views in greater detail and to respond to the applicant. Our contact information is provided at the end of our intervention. I The application by Rogers Sports Inc. 4 This section sets out the facts and arguments being made by RSI in support of the application that is asking the CRTC to approve. -

The CRTC's Enforcement of Canada's Broadcast Legislation: 'Concern', 'Serious Concern' and 'Grave Concern'

Canadian Journal of Law and Technology Volume 5 Number 3 Article 1 8-1-2006 The CRTC's Enforcement of Canada's Broadcast Legislation: 'Concern', 'Serious Concern' and 'Grave Concern' Monica Auer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/cjlt Part of the Computer Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Privacy Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Monica Auer, "The CRTC's Enforcement of Canada's Broadcast Legislation: 'Concern', 'Serious Concern' and 'Grave Concern'" (2006) 5:3 CJLT. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Schulich Law Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Journal of Law and Technology by an authorized editor of Schulich Law Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The CRTC’s Enforcement of Canada’s Broadcasting Legislation: ‘‘Concern’’, ‘‘Serious Concern’’, and ‘‘Grave Concern’’ M.L. Auer, M.A., LL.M.† I. Introduction again in 2004, by the Parliamentary Standing Com- mittee on Heritage. Generally speaking, however, these his paper describes results from a quantitative study studies used case-based analyses wherein the conclusions T of the enforcement by the Canadian Radio-televi- necessarily depended on the cases reviewed. This paper sion and Telecommunications Commission 1 (CRTC or adopts a broadly based empirical approach to describe Commission) over the last several decades of Canada’s and analyze the CRTC’s regulation of its conventional, broadcasting legislation and its own regulations. Estab- over-the-air radio licensees from 1968 to 2005. lished by Parliament in 1968, the CRTC is a quasi-judi- This paper concludes that the CRTC uses informal cial regulatory agency that administers Canada’s Broad- sanctions, rather than the penalties set out by Parliament casting Act, 1991 2 as well as the nation’s in Canada’s broadcasting legislation, and that the telecommunications legislation. -

The Social Costs of Industrial Growth in the Subarctic Regions Of

Western University Scholarship@Western University of Western Ontario - Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository May 2015 The oS cial Costs of Industrial Growth in the Sub- Arctic Regions of "Canada" Caylee T. Cody The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Anton Allahar The University of Western Ontario Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, Economic Policy Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Health Policy Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Infrastructure Commons, Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, Political Science Commons, Public Administration Commons, Public Policy Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Rural Sociology Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, and the Social Policy Commons Recommended Citation Cody, Caylee T., "The ocS ial Costs of Industrial Growth in the Sub-Arctic Regions of "Canada"" (2015). University of Western Ontario - Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. Paper 2820. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Western Ontario - Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

GRILLE DE CHAÎNES NATIONALE (ORDRE NUMÉRIQUE) Octobre 2020

GRILLE DE CHAÎNES NATIONALE (ORDRE NUMÉRIQUE) Octobre 2020 100 Chaînes Atlantique HD 164 Citytv Winnipeg HD 238 CBS West HD 327 ESPN Classic 101 Global Halifax HD 170 Chaînes Saskatchewan HD 239 Fox West HD 328 Sportsnet World HD 102 CBC Halifax HD 171 Global Regina HD 240 NBC West HD 329 beIN SPORTS HD 103 CTV Halifax HD 172 CBC Regina HD 241 PBS Seattle HD 330 WWE Network HD 104 CTV2 Atlantic HD 173 CTV Regina HD 242 PBS Spokane HD 331 Leafs TV HD 105 Global New Brunswick HD 174 Citytv Saskatchewan HD 243 myTV38 HD (WSBK Boston) 336 Fox Sports Racing HD 106 CBC Frederiction HD 175 Global Saskatoon HD 244 PIX 11 HD (The CW New York) 337 Cowboy Channel Canada HD 107 CTV Saint John HD 176 CTV Saskatoon HD 245 WGN Chicago HD 338 The Water Channel HD 108 CTV Moncton HD 177 CTV Prince Albert HD 246 KTLA 5 CW Los Angeles HD 350 Chaînes pour enfants HD 109 CBC Charlottetown HD 178 CTV Yorkton HD 252 The Weather Network HD 351 Treehouse HD 110 CTV Sydney HD 179 CKSA Lloydminster HD 253 aptn HD 352 Disney Junior HD 111 CBC Newfoundland HD 180 CITL Lloydminster HD 254 CPAC HD 353 Family Jr. HD 112 NTV Newfoundland HD 181 Northern Legislative Assembly 255 CBC News Network HD 361 Nickelodeon HD 120 Chaînes Québec HD (anglais) 182 OMNI Prairies HD 256 CTV News Channel HD 362 YTV HD 121 Global Montreal HD 190 Chaînes Alberta HD 257 BNN Bloomberg HD 363 YTV West HD 122 CBC Montreal HD 191 Global Edmonton HD 258 CNN HD 364 Disney XD HD 123 CTV Montreal HD 192 CBC Edmonton HD 259 HLN HD 365 CHRGD HD 124 Citytv Montreal HD 193 CTV Edmonton HD 260 MSNBC -

1990 CTV Agreement

ARTICLE 1 – RECOGNITION, SCOPE AND APPLICATION 101 CTV Recognizes ACTRA as the sole bargaining agent for performers engaged by CTV for the production of programs for broadcast (save for the exclusions contained in Article 2 hereof). For the purpose of this Agreement, when CTV enters into a contract with any person or corporation for the provision of services of a performer, such performer shall be deemed to be a performer engaged by CTV. 102 This Agreement shall apply to all performers as defined herein participating in programs produced live or recorded by any means whatsoever for distribution by syndication or by any other method. This includes the sale and distribution of such programs to broadcasting outlets situated with and/or beyond the boundaries of Canada. 103 This Agreement represents minimum rates, fees and working conditions. All persons engaged in any category of performance within the scope of this Agreement shall be compensated at rates not less than those provided herein and not be subject to working conditions that are less favourable than the provisions of this Agreement. 104 The parties acknowledge that the performers represented herein by the Alliance are self-employed. However, if any or all of the performers be declared by any third party, the decisions of which are legally enforceable, to have the status of employees, the parties agree that, with respect to such performers and pursuant to the applicable Provincial or Federal legislation, the Agreement shall recognize the Alliance as the exclusive bargaining agent for a unit of such employees. Notwithstanding its application as a collective agreement, this Agreement shall, in addition, continue in full force and effect to govern the conditions of engagement of performers not declared to be employees. -

Terrorism, Ethics and Creative Synthesis in the Post-Capitalist Thriller

The Post 9/11 Blues or: How the West Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Situational Morality - Terrorism, Ethics and Creative Synthesis in the Post-Capitalist Thriller Patrick John Lang BCA (Screen Production) (Honours) BA (Screen Studies) (Honours) Flinders University PhD Dissertation School of Humanities and Creative Arts (Screen and Media) Faculty of Education, Humanities & Law Date of Submission: April 2017 i Table of Contents Summary iii Declaration of Originality iv Acknowledgements v Chapter One: A Watershed Moment: Terror, subversion and Western ideologies in the first decade of the twenty-first century 1 Chapter Two: Post-9/11 entertainment culture, the spectre of terrorism and the problem of ‘tastefulness’ 18 A Return to Realism: Bourne, Bond and the reconfigured heroes of 21st century espionage cinema 18 Splinter cells, stealth action and “another one of those days”: Spies in the realm of the virtual 34 Spies, Lies and (digital) Videotape: 21st Century Espionage on the Small Screen 50 Chapter Three: Deconstructing the Grid: Bringing 24 and Spooks into focus 73 Jack at the Speed of Reality: 24, torture and the illusion of real time or: “Diplomacy: sometimes you just have to shoot someone in the kneecap” 73 MI5, not 9 to 5: Spooks, disorder, control and fighting terror on the streets of London or: “Oh, Foreign Office, get out the garlic...” 91 Chapter Four: “We can't say anymore, ‘this we do not do’”: Approaching creative synthesis through narrative and thematic considerations 108 Setting 108 Plot 110 Morality 111 Character 114 Cinematic aesthetics and the ‘culture of surveillance’ 116 The role of technology 119 Retrieving SIGINT Data - Documenting the Creative Artefact 122 ii The Section - Series Bible 125 The Section - Screenplays 175 Episode 1.1 - Pilot 175 Episode 1.2 - Blasphemous Rumours 239 Episode 1.9 - In a Silent Way 294 Bibliography 347 Filmography (including Television and Video Games) 361 iii Summary The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 have come to signify a critical turning point in the geo-political realities of the Western world. -

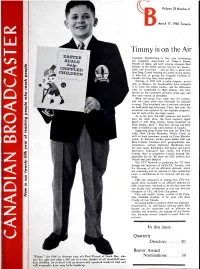

Timmy Is on the Air

Volume 25 Number 6 March 17, 1966 Toronto Timmy is on the Air EASTER Canadian broadcasting is this year celebrating SEALS the twentieth anniversary of Timmy's Easter help Parade of Stars, and with veteran showman Mart Kenney at the wheel and not one but two shows- CRIPPLED radio and television - and no less a guest star CRILDREN than Bing Crosby heading the roster of top talent, :ed. it bids fair to giving the Crippled Children of .. Canada the filip their drive .. .... needs. v Starting in 1947 with a radio program carried only in Ontario, the broadcasters have extended it to cover the whole country, and the difference must be remarkable to Mart Kenney who first served on the committee nineteen years ago, and this year returns as president. When television first came into the picture, half the radio show was televised for national viewing. This developed into a one -hour simulcast for both radio and television. Then, last year, the simulcast was replaced by two separate programs, one for each of the electronic media. As in the past, the CBC produces and distrib- utes the radio show, the final segment, taped March 6 with Bing Crosby, being broadcast on Palm Sunday, April 3. This hour special has been made available to any radio station in Canada. Supporting Bing Crosby this year are The Four Lads, New Christy Minstrels, Petula Clark, as well as such prominent people as Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, hockey great Bobby Hull and Miss Canada. Canadian acts, geographically rep- resentative, include Katherine MacKinnon from the east coast, Winnipeg's Ted Komar and Lance Harrison's Vancouver jazz combo. -

Download (97Kb)

Canada LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/103004/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Decillia, Brooks (2020) Canada. In: Merskin, Debra L., (ed.) The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Mass Media and Society. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, 250 - 255. ISBN 9781483375533 https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483375519.n100 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Mass Media and Society Canada Brooks DeCillia Edited by: Debra L. Merskin Book Title: The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Mass Media and Society Chapter Title: "Canada" Pub. Date: 2020 Access Date: December 13, 2019 Publishing Company: SAGE Publications, Inc. City: Thousand Oaks, Print ISBN: 9781483375533 Online ISBN: 9781483375519 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483375519.n100 Print pages: 250-255 As a country and a culture, Canada is both vast and complex. Its media system is, not surprisingly, equally big and complicated. Shaped by its enormous geography, distinct history, and multicultural makeup, Canada is a democratic federal state, with two official languages—French and English—and an indigenous population that maintains its sovereignty (i.e., the right to self- government). Along with its advanced economy and ethnically diverse population, the country’s media system is modern and sophisticated. -

Media Ethics: Approach and Management

Media ethics: approach and management Bell Media is Canada’s leading content creation company with premier assets in television, radio, out-of-home advertising, and digital media. Bell Media owns 35 local television stations led by CTV, Canada’s most-watched television network, and the French-language Noovo network in Québec; and 27 specialty channels, including leading specialty services TSN and RDS. CTV News was founded in 1971. It is part of Bell Media, which is part of BCE, a publicly traded company. CTV News is committed to upholding principles of journalistic independence and is governed by a Journalistic Independence Policy ensuring independence and non- interference between BCE and CTV News while remaining in compliance with the Broadcast Act and relevant industry codes. Journalistic integrity of news programming It is our job to tell Canadian stories and to reflect the country to itself. It is our job to be impartial. It is our job to be independent from those seeking to influence our news programming. It is our job to reflect the multicultural and multiracial dynamics of Canada. CTV News’ mandate is to uphold journalistic integrity and independence under all circumstances and at all times, without exception. As a reputable news organization in a democracy, it is the fundamental purpose of CTV News to enable Canadians to know what is happening and to clarify events so they may form their own conclusions. This is done through accurate, fair, and relevant stories told in a clear and compelling way. With a perspective that is uniquely Canadian and via a network of national, international, and local news operations, our mission is to be Canada’s most trusted news source, providing the most timely and relevant news and information on all platforms while adhering to the highest standards of journalism at all times. -

Domestic Supply to Global Demand: Reframing the Challenge of Canadian English-Language Television Drama

DOMESTIC SUPPLY TO GLOBAL DEMAND: REFRAMING THE CHALLENGE OF CANADIAN ENGLISH-LANGUAGE TELEVISION DRAMA by Irene S. Berkowitz A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in the Joint Graduate Program in Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © Irene S. Berkowitz 2016 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract DOMESTIC SUPPLY TO GLOBAL DEMAND: REFRAMING THE CHALLENGE OF CANADIAN ENGLISH-LANGUAGE TELEVISION DRAMA DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY, 2016 IRENE S. BERKOWITZ COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE RYERSON UNIVERSITY AND YORK UNIVERSITY As online TV delivery disrupts conventional TV broadcasting and unbundles TV cable channels, allowing consumers to choose programs and TV brands more directly, hit content is “king” more than ever before. This dissertation offers a new analysis of Canadian English-language TV drama content’s failure to mature into a popular genre or robust economic sector since its introduction in the 1960s, and suggests ways that the Canadian English-language TV drama value chain might be strategically adjusted in response to global market disruption, by strengthening the development phase.