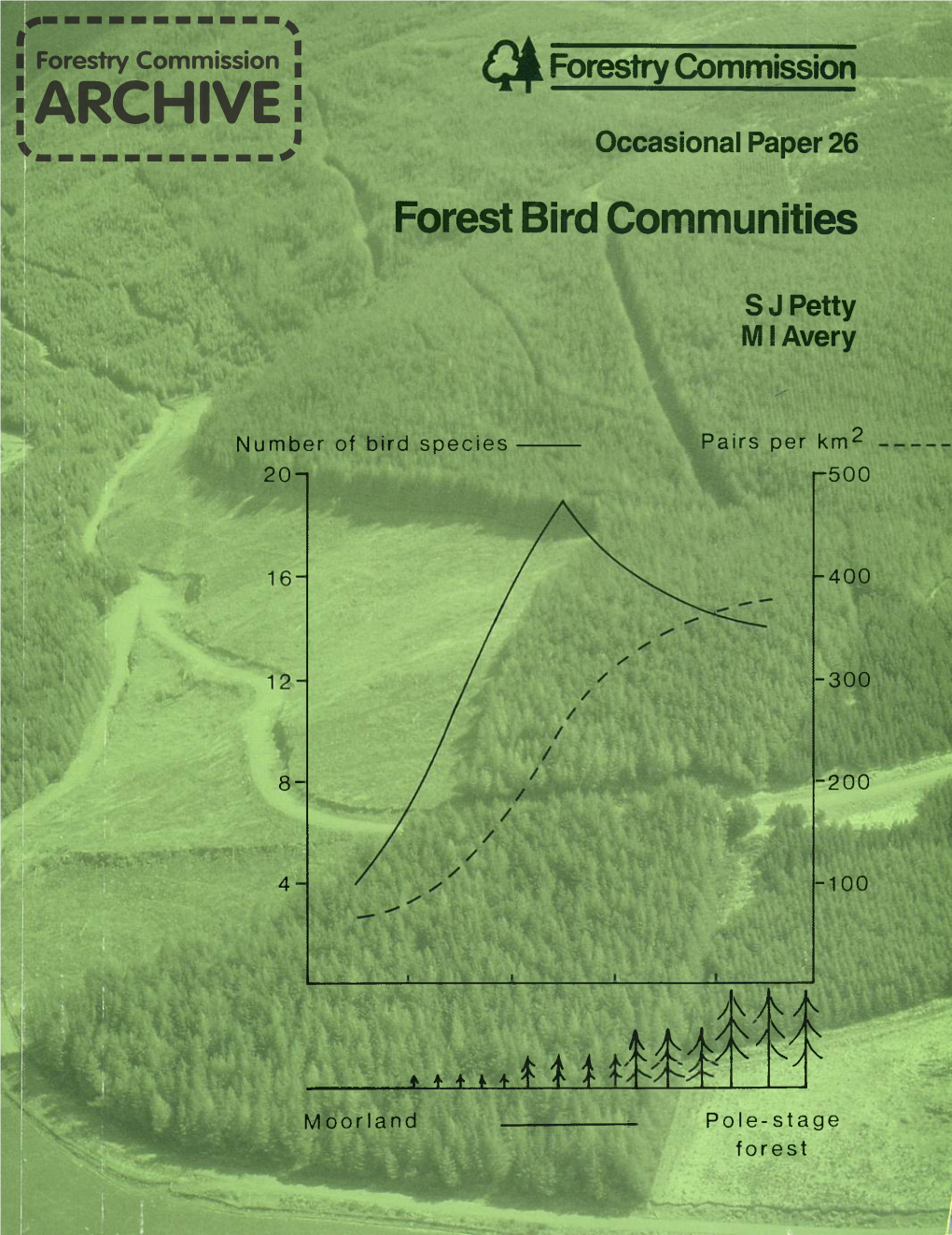

Forest Bird Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hunting and Game Preservation Act

HUNTING AND GAME PRESERVATION ACT Prom. SG. 78/26 Sep 2000, amend. SG. 26/20 Mar 2001, amend. SG. 77/9 Aug 2002, amend. SG. 79/16 Aug 2002, amend. SG. 88/4 Nov 2005, amend. SG. 82/10 Oct 2006, amend. SG. 108/29 Dec 2006, amend. SG. 64/7 Aug 2007, amend. SG. 43/29 Apr 2008, amend. SG. 67/29 Jul 2008, amend. SG. 69/5 Aug 2008, amend. SG. 91/21 Oct 2008, amend. SG. 6/23 Jan 2009, amend. SG. 80/9 Oct 2009, amend. SG. 92/20 Nov 2009, amend. SG. 73/17 Sep 2010, amend. SG. 89/12 Nov 2010, amend. SG. 8/25 Jan 2011, amend. SG. 19/8 Mar 2011, amend. SG. 39/20 May 2011, amend. SG. 77/4 Oct 2011, amend. SG. 38/18 May 2012, amend. SG. 60/7 Aug 2012, amend. SG. 77/9 Oct 2012, amend. SG. 102/21 Dec 2012, amend. SG. 15/15 Feb 2013, amend. SG. 62/12 Jul 2013, amend. SG. 60/7 Aug 2015, amend. SG. 14/19 Feb 2016, amend. SG. 58/18 Jul 2017, amend. SG. 63/4 Aug 2017, amend. and suppl. SG. 17/23 Feb 2018, suppl. SG. 61/24 Jul 2018, suppl. SG. 77/18 Sep 2018, amend. and suppl. SG. 37/7 May 2019, amend. and suppl. SG. 74/20 Sep 2019 Chapter one. GENERAL PROVISIONS Art. 1. The Act shall provide the relations connected with the ownership, preservation and management of the game, the organisation of hunting economy, the right to hunt and the trade with game and game products. -

The Wild Rabbit: Plague, Polices and Pestilence in England and Wales, 1931–1955

The wild rabbit: plague, polices and pestilence in England and Wales, 1931–1955 by John Martin Abstract Since the eighteenth century the rabbit has occupied an ambivalent position in the countryside. Not only were they of sporting value but they were also valued for their meat and pelt. Attitudes to the rabbit altered though over the first half of the century, and this paper traces their redefinition as vermin. By the 1930s, it was appreciated that wild rabbits were Britain’s most serious vertebrate pest of cereal crops and grassland and that their numbers were having a significant effect on agricultural output. Government took steps to destroy rabbits from 1938 and launched campaigns against them during wartime, when rabbit was once again a form of meat. Thereafter government attitudes to the rabbit hardened, but it was not until the mid-1950s that pestilence in the form of a deadly virus, myxomatosis, precipitated an unprecedented decline in their population. The unprecedented decline in the European rabbit Oryctolagus( cuniculus) in the mid- twentieth century is one of the most remarkable ecological changes to have taken place in Britain. Following the introduction of myxomatosis into Britain in September 1953 at Bough Beech near Edenbridge in Kent, mortality rates in excess of 99.9 per cent were recorded in a number of affected areas.1 Indeed, in December 1954, the highly respected naturalist Robin Lockley speculated that 1955 would constitute ‘zero hour for the rabbit’, with numbers being lower by the end of the year than at any time since the eleventh century.2 In spite of the rapid increases in output and productivity which British agriculture experienced in the post-myxomatosis era, the importance of the disease as a causal factor in raising agricultural output has been largely ignored by agricultural historians.3 The academic neglect of the rabbit as a factor influencing productivity is even more apparent in respect of the pre-myxomatosis era, particularly the period before the Second World War. -

Bird Observer

Bird Observer VOLUME 39, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2011 HOT BIRDS On November 20 the Hampshire Bird Club was waiting at Quabbin headquarters for the rest of the group to arrive when Larry Therrien spotted a flock of 19 swans in the distance— Tundra Swans! Ian Davies took this photograph (left). Since 2003 Cave Swallows have been a specialty of November, showing up in coastal locations in increasing numbers over the years. This year there was a flurry of reports along the New England coast. On Thanksgiving Day, Margo Goetschkes took this photograph (right) of one of the birds at Salisbury. On November 30, Vern Laux got a call from a contractor reporting a “funny bird” at the Nantucket dump. Vern hustled over and was rewarded with great views of this Fork-tailed Flycatcher (left). Imagine: you’re photographing a Rough- legged Hawk in flight, and all of a sudden it is being mobbed—by a Northern Lapwing (right)! That’s what happened to Jim Hully on December 2 on Plum Island. This is only the second state record for this species, the first being in Chilmark in December of 1996. On April 9, Keelin Miller found an interesting gull at Kalmus Beach in Hyannis. As photographs were circulated, opinions shifted toward a Yellow-legged Gull (left). Check out Jeremiah Trimble’s photo from April 13. CONTENTS BIRDING THE LAKEVILLE PONDS OF PLYMOUTH COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS Jim Sweeney 73 THE FINAL YEAR OF THE BREEDING BIRD ATLAS: GOING OVER THE TOP John Galluzzo 83 37 YEARS OF NIGHTHAWKING Tom Gagnon 86 LEIF J ROBINSON: MAY 21, 1939 – FEBRUARY 28, 2011 Soheil Zendeh 93 FIELD NOTES Double-crested Cormorant Has Trouble Eating a Walking Catfish William E. -

Flight of the Bumblebee (Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov) Stephen Reid | Elementary Music (Osceola) | Hickory Tree Elementary Mp3 Available Here

2018 Young People’s Concerts Beyond the Screen! Teacher Guidebook Thank you to our 2018 Sponsors! Daytona Beach Symphony Society Thank you also to our 2018 Partners: Orange County Public Schools School District of Osceola Volusia County Schools United Arts of Central Florida Visit OrlandoPhil.org/family-friendly to find more great offerings for kids and families! Meet our Guidebook Team! Putting together a Young People’s Concert requires hard work and the dedication of dozens of people over many months. Please welcome some of the key individuals who make the Young People’s Concert possible! Meet our Guidebook Team! The guidebook team is comprised of certified, veteran teachers who are passionate about music, the arts, and making learning fun! Christy Garton Cindy Krulick Finale from Firebird (Visual Art) Star Spangled Banner OCPS Resource Teacher Finale from Firebird Visual Art (K-12) Dommerich Elementary Orange County Public Schools [email protected] [email protected] Emily Light Katie Grace Miller In the Hall of the Mountain King Tempus Fugit Champion Elementary Sorcerer's Apprentice Volusia County Schools Mambo from West Side Story [email protected] Lake George Elementary Orange County Public Schools [email protected] Denise Mills Anka Pink Duo des fleurs / Sous le dôme épais Hoedown from Rodeo Lake Whitney Elementary OCPS Resource Teacher Orange County Public Schools (Music K-12) [email protected] Orange County Public Schools [email protected] Stephen Reid Dr. Leia Barrett Flight of the Bumblebee Director of Education Hickory Tree Elementary School Orlando Philharmonic Orchestra School District of Osceola [email protected] [email protected] If you have any questions about particular lessons, please contact the teacher who created the lesson originally. -

ECOS 37-2-60 Reintroductions and Releases on the Isle Of

ECOS 37(2) 2016 ECOS 37(2) 2016 Reintroductions and releases on the Isle of Man Lessons from recent retreats Recent proposals for the release of white-tailed sea eagles and red squirrels on the Isle of Man received very different treatment, perhaps reflecting public perception of the animals and the public profile of the proponents, but also the political landscape of the island. NICK PINDER The Manx legal context The Isle of Man is a Crown dependency outside the EU but inside a common customs union with the United Kingdom. The Island can request that Westminster’s laws are extended to it but usually the Island passes its own laws which it promulgates at the annual Tynwald ceremony. Since it has a special relationship with the European Union, under Protocol 3, EU legislation covering agricultural and other trade is Point of Ayre: The Ayres is a large area of coastal heath and dune grassland in the north of the Isle of Mann usually translated into Manx law, as is UK law affecting customs controls. The 1980 island and location of the only National Nature Reserve. Endangered Species Act was therefore swiftly adopted in the Isle of Man but the Photo: Nick Pinder Wildlife and Countryside Act of the same year was not. A test for the legislation came in the early 1990s when some fox carcases turned When I arrived on the Isle of Man in 1987, the only wildlife legislation was a up. One was allegedly run over and then someone came forward having shot two dated Protection of Birds Act (1932-1975) but the newly formed Department of adults at a den site and dug up several cubs. -

Rural Discontent in Derbyshire 1830·1850

RURAL DISCONTENT IN DERBYSHIRE 1830·1850 Alan Frank Jones Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Sheffield January 2004 ii Alan Frank Jones RURAL DISCONTENT IN DERBYSlllRE 1830-1850 ABSTRACT Social protest, especially in agricultural regions, has occupie~ and caused considerable debate among, historians for many years. This thesis seeks to add to this debate, by looking at various forms of protest in Derbyshire between 1830 and 1850. This thesis examines three aspects of criminal activity: poaching, arson and animal maiming. It contends that none of these crimes can simply be categorised as acts of protest. In conjunction with an investigation of these three crimes, acts of protest such as strikes and episodes of reluctance to conform are also discussed. It argues that the motives behind various criminal activities and anti-authority behaviour were varied and complex. Arson and animal maiming were rarely co-ordinated, mostly they were individual attacks. However, on a few occasions both arson and animal maiming were directed against certain people. In the instances of poaching, there were more proven cases of gang participation than in either arson or animal maiming, with groups of men raiding game preserves. However, the great majority of raids were individual undertakings. What is more, poaching was carried out on a greater scale throughout the county than either arson or animal maiming. This thesis seeks to put these activities into the context of economic and social change in Derbyshire between 1830 and 1850. It maintains that there was a breaking down of the old social order. -

Describing Species

DESCRIBING SPECIES Practical Taxonomic Procedure for Biologists Judith E. Winston COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 1999 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data © Winston, Judith E. Describing species : practical taxonomic procedure for biologists / Judith E. Winston, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-231-06824-7 (alk. paper)—0-231-06825-5 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Biology—Classification. 2. Species. I. Title. QH83.W57 1999 570'.1'2—dc21 99-14019 Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 98765432 p 10 98765432 The Far Side by Gary Larson "I'm one of those species they describe as 'awkward on land." Gary Larson cartoon celebrates species description, an important and still unfinished aspect of taxonomy. THE FAR SIDE © 1988 FARWORKS, INC. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Universal Press Syndicate DESCRIBING SPECIES For my daughter, Eliza, who has grown up (andput up) with this book Contents List of Illustrations xiii List of Tables xvii Preface xix Part One: Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 3 Describing the Living World 3 Why Is Species Description Necessary? 4 How New Species Are Described 8 Scope and Organization of This Book 12 The Pleasures of Systematics 14 Sources CHAPTER 2. BIOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE 19 Humans as Taxonomists 19 Biological Nomenclature 21 Folk Taxonomy 23 Binomial Nomenclature 25 Development of Codes of Nomenclature 26 The Current Codes of Nomenclature 50 Future of the Codes 36 Sources 39 Part Two: Recognizing Species 41 CHAPTER 3. -

Music Jazz Booklet

AQA Music A level Area of Study 5: Jazz NAME: TEACHER: 1 Contents Page Contents Page number What you will be studying 3 Jazz Timeline and background 4 Louis Armstrong 8 Duke Ellington 15 Charlie Parker 26 Miles Davis 33 Pat Metheny 37 Gwilym Simcock 40 Essay Questions 43 Vocabulary 44 2 You will be studying these named artists: Artists Pieces Louis Armstrong St. Louis Blues (1925, Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith) Muskrat Ramble (1926, Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five) West End Blues (1928, Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five) Stardust (1931, Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra) Duke Ellington The Mooche (1928, Duke Ellington and his Orchestra) Black and Tan (1929, Duke Ellington and his Orchestra) Ko-Ko (1940, Duke Ellington and his Orchestra) Come Sunday from Black, Brown and Beige (1943) Charlie Parker Ko-Ko (1945, Charlie Parker’s Reboppers) A Night in Tunisia (1946, Charlie Parker Septet) Bird of Paradise (1947, Charlie Parker Quintet) Bird Gets the Worm (1947, Charlie Parker All Stars) Miles Davis So What, from Kind of Blue (1959) Shhh, from In a Silent Way (1969) Pat Metheny (Cross the) Heartland, from American Garage (1979) Are you Going with Me?, from Offramp (1982) Gwilym Simcock Almost Moment, from Perception (2007) These are the Good Days, from Good Days at Schloss Elamau (2014) What you need to know: Context about the artist and the era(s) in which they were influential and the effect of audience, time and place on how the set works were created, developed and performed Typical musical features of that artist and their era – their purpose and why each era is different Musical analysis of the pieces listed for use in your exam How to analyse unfamiliar pieces from these genres Relevant musical vocabulary and terminology for the set works (see back of pack) 3 Jazz Timeline 1960’s 1980’s- current 1940’s- 1950’s 1920’s 1930’s 1940’s 1960’s- 1980’s 1870’s – 1910’s 1910-20’s St. -

POVERTY, PROTEST and SPORT: POACHING in the EAST MIDLANDS C.1820-C.1900 ROSEMARY MUGE, MA. Thesis Submitted to the University Of

POVERTY, PROTEST AND SPORT: POACHING IN THE EAST MIDLANDS c.1820-c.1900 ROSEMARY MUGE, MA. Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2017 Abstract In the East Midlands counties of Derbyshire, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire levels of poaching equalled or exceeded those in many counties which are thought of as prime poaching areas. Using principally Criminal Registers, Game Laws Returns to Parliament, and local newspapers of the period, this study shows that people poached from three motives: because they were poor; because poaching was a sport; and as a protest. Day and night poachers, including night poaching gangs frequently involved in affrays, pursued their activities undeterred by the efforts at prevention of the landowners, police and courts. Poaching here was predominantly for ground game and declined in the last quarter of the century, but continued to be a source of anger and frustration for game preservers and the authorities to the end of the period. The poaching war in these counties, waged in an area with large aristocratic estates but where extreme game preservation was viewed critically, was not perceived as impacting on law and order in general. This was unlike Lancashire, where the activities of poachers were regarded as being a threat to the fabric of society. The causes of these differences between the East Midlands and Lancashire were rooted in police practice, attitudes to game preservation, and differences in gentry sport and hunting. (Total words in thesis: 90,313) Acknowledgements Having begun to study history twenty years ago and finally submitted this thesis in retirement, there are many people to whom I am beholden. -

In Your Own Sweet Way

In Your Own Sweet Way A study of tertiary jazz pianists’ individualised approaches to practice and performance Volume 1 Thesis Daniel Anthony Gough B Mus (Hons Class 1), Grad Dip Ed A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sydney Conservatorium of Music The University of Sydney 2018 ii Declaration This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Name: Daniel A. Gough Date: September 30, 2018 iii Abstract Set out in three volumes (Vol. 1 Thesis, Vol. 2 Transcriptions, Vol. 3 Appendices) and engaging the history of jazz transmission, this study investigates the ways aspiring jazz pianists practise in order to develop their own personal voice or musical identity, the supreme goal of the jazz musician. To date, this process has not been well served by research. It is commonly held that being an improvisational art form, jazz cannot be taught, at least not in a conventional way, and that jazz musicians search out for themselves what they wish to learn and who they wish to learn it from. When around the middle of last century jazz instruction began to move from the street and club to the formal institution, many experts became alarmed that this would have a homogenising effect on the music. -

Systema Naturae. the Classification of Living Organisms

Systema Naturae. The classification of living organisms. c Alexey B. Shipunov v. 5.601 (June 26, 2007) Preface Most of researches agree that kingdom-level classification of living things needs the special rules and principles. Two approaches are possible: (a) tree- based, Hennigian approach will look for main dichotomies inside so-called “Tree of Life”; and (b) space-based, Linnaean approach will look for the key differences inside “Natural System” multidimensional “cloud”. Despite of clear advantages of tree-like approach (easy to develop rules and algorithms; trees are self-explaining), in many cases the space-based approach is still prefer- able, because it let us to summarize any kinds of taxonomically related da- ta and to compare different classifications quite easily. This approach also lead us to four-kingdom classification, but with different groups: Monera, Protista, Vegetabilia and Animalia, which represent different steps of in- creased complexity of living things, from simple prokaryotic cell to compound Nature Precedings : doi:10.1038/npre.2007.241.2 Posted 16 Aug 2007 eukaryotic cell and further to tissue/organ cell systems. The classification Only recent taxa. Viruses are not included. Abbreviations: incertae sedis (i.s.); pro parte (p.p.); sensu lato (s.l.); sedis mutabilis (sed.m.); sedis possi- bilis (sed.poss.); sensu stricto (s.str.); status mutabilis (stat.m.); quotes for “environmental” groups; asterisk for paraphyletic* taxa. 1 Regnum Monera Superphylum Archebacteria Phylum 1. Archebacteria Classis 1(1). Euryarcheota 1 2(2). Nanoarchaeota 3(3). Crenarchaeota 2 Superphylum Bacteria 3 Phylum 2. Firmicutes 4 Classis 1(4). Thermotogae sed.m. 2(5). -

Front Matter Template

Copyright by Martin Norgaard 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Martin Norgaard Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Descriptions of Improvisational Thinking by Artist-level Jazz Musicians Committee: Robert A. Duke, Co-Supervisor Laurie S. Young, Co-Supervisor Lowell J. Bethel Eugenia Costa-Giomi Jeffrey L. Hellmer Judith A. Jellison Bruce W. Pennycook Descriptions of Improvisational Thinking by Artist-level Jazz Musicians by Martin Norgaard, M.A., B.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2008 Dedication Jonna Hindsgaul Kai Nørgaard Leif Hindsgaul Descriptions of Improvisational Thinking by Artist-level Jazz Musicians Publication No._____________ Martin Norgaard, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2008 Supervisors: Robert A. Duke and Laurie S. Young I investigated the thought processes of seven artist-level jazz musicians. Although jazz artists in the past have spoken extensively about the improvisational process, most have described improvisation only in general terms or have discussed specific recorded improvisations long after the recordings had been made. To date, no study has attempted to record artists’ perceptions of their improvisational thinking regarding improvisations they had just performed. Seven jazz artists recorded an improvised solo based on a blues chord progression accompanied only by a drum track. New technologies made it possible to notate the recorded material as it was being performed. After completing their improvisations, participants described in a directed interview, during which they listened to their playing and looked at the notation of their solos, the thinking processes that led to the realization of their performances.