Constructing Gender in Japanese Popular Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tesi Di Laurea

Corso di Laurea magistrale in LINGUE E ISTITUZIONI ECONOMICHE E GIURIDICHE DELL’ASIA E DELL’AFRICA MEDITERRANEA [LM4-12] Tesi di Laurea L’arte del silenzio Il simbolismo nel cinema di Shinkai Makoto Relatore Ch. Prof.ssa Roberta Maria Novielli Correlatore Ch. Prof. Davide Giurlando Laureando Carlotta Noè Matricola 838622 Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 要旨要旨要旨 この論文の目的は新海誠というアニメーターの映画的手法を検討する ことである。近年日本のアニメーション業界に出現した新海誠は、写実的な スタイルで風景肖像を描くことと流麗なアニメーションを創作することと憂 鬱な物語で有名である。特に、この検討は彼の作品の中にある自分自身の人 生、愛情、人間関係の見方を伝えるための記号型言語に集中するつもりであ る。 第一章には新海誠の伝記、フィルモグラフィとその背景にある経験に 焦点を当たっている。 第二章は監督の映画のテーマに着目する。なかでも人は互いに感情を 言い表せないこと、離れていること、そして愛のことが一番大切である。確 かに、彼の映画の物語は愛情を中心に回るにもかかわらず、結局ハッピーエ ンドの映画ではない。換言すれば、新海誠の見方によると、愛は勝つはずで はない。新海誠は別の日本のアニメーターや作家から着想を得ている。その ため、次はそれに関係があるテクニックとスタイルを検討するつもりである。 第三章には新海誠の作品の分析を通して視覚言語と記号型言語が発表 される。一般的な象徴以外に、伝統、神話というふうに、日本文化につなが る具体的なシンボルがある。一方、西洋文化に触れる言及もある。例えば、 音楽や学術研究に言及する。 こうして、新海誠は異なる文化を背景を問わず観客の皆に同じような感情を 感じさせることができる。 最後に、後付けが二つある。第一に、新海誠が演出したテレビコマー シャルとプロモーションビデオが分析する。第二に、新海誠と宮崎駿という アニメーターを比較する。新海誠の芸術様式は日本のアニメーションを革新 したから、“新宮崎”とよく呼ばれている。にもかかわらず、この呼び名を 離れる芸術様式の分野にも、筋の分野にも様々な差がある。特に、宮崎駿の アニメーションに似ている新海誠の「星を追うこども」という映画を検討す る。 1 L’ARTE DEL SILENZIO Il simbolismo nel cinema di Shinkai Makoto 要旨要旨要旨 …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….Pg.1 INTRODUZIONE …………………………………………………………………………………………..Pg.4 CAPITOLO PRIMO: Shinkai Makoto……………………………………………………………………………………………Pg.6 1.1 Shinkai Makoto, animatore per caso 1.2 Filmografia, sinossi e riconoscimenti CAPITOLO SECONDO : L’arte di Shinkai Makoto……………………………………………………………………………..Pg.18 -

Download the Program (PDF)

ヴ ィ ボー ・ ア ニ メー シ カ ョ ワ ン イ フ イ ェ と ス エ ピ テ ッ ィ Viborg クー バ AnimAtion FestivAl ル Kawaii & epikku 25.09.2017 - 01.10.2017 summAry 目次 5 welcome to VAF 2017 6 DenmArk meets JApAn! 34 progrAmme 8 eVents Films For chilDren 40 kAwAii & epikku 8 AnD families Viborg mAngA AnD Anime museum 40 JApAnese Films 12 open workshop: origAmi 42 internAtionAl Films lecture by hAns DybkJær About 12 important ticket information origAmi 43 speciAl progrAmmes Fotorama: 13 origAmi - creAte your own VAF Dog! 44 short Films • It is only possible to order tickets for the VAF screenings via the website 15 eVents At Viborg librAry www.fotorama.dk. 46 • In order to pick up a ticket at the Fotorama ticket booth, a prior reservation Films For ADults must be made. 16 VimApp - light up Viborg! • It is only possible to pick up a reserved ticket on the actual day the movie is 46 JApAnese Films screened. 18 solAr Walk • A reserved ticket must be picked up 20 minutes before the movie starts at 50 speciAl progrAmmes the latest. If not picked up 20 minutes before the start of the movie, your 20 immersion gAme expo ticket order will be annulled. Therefore, we recommended that you arrive at 51 JApAnese short Films the movie theater in good time. 22 expAnDeD AnimAtion • There is a reservation fee of 5 kr. per order. 52 JApAnese short Film progrAmmes • If you do not wish to pay a reservation fee, report to the ticket booth 1 24 mAngA Artist bAttle hour before your desired movie starts and receive tickets (IF there are any 56 internAtionAl Films text authors available.) VAF sum up: exhibitions in Jane Lyngbye Hvid Jensen • If you wish to see a movie that is fully booked, please contact the Fotorama 25 57 Katrine P. -

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006 BECAUSE FILMS INSPIRE... WONDER There’s more to discover about film and television British Film Institute through the BFI. Our world-renowned archive, cinemas, festivals, films, publications and learning Report & Financial resources are here to inspire you. Statements 2006 Contents The mission about the BFI 3 Great expectations Governors’ report 5 Out of the past Archive strategy 7 Walkabout Cultural programme 9 Modern times Director’s report 17 The commitments key aims for 2005/06 19 Performance Financial report 23 Guys and dolls how the BFI is governed 29 Last orders Auditors’ report 37 The full monty appendices 57 The mission ABOUT THE BFI The BFI (British Film Institute) was established in 1933 to promote greater understanding, appreciation and access to fi lm and television culture in Britain. In 1983 The Institute was incorporated by Royal Charter, a copy of which is available on request. Our mission is ‘to champion moving image culture in all its richness and diversity, across the UK, for the benefi t of as wide an audience as possible, to create and encourage debate.’ SUMMARY OF ROYAL CHARTER OBJECTIVES: > To establish, care for and develop collections refl ecting the moving image history and heritage of the United Kingdom; > To encourage the development of the art of fi lm, television and the moving image throughout the United Kingdom; > To promote the use of fi lm and television culture as a record of contemporary life and manners; > To promote access to and appreciation of the widest possible range of British and world cinema; and > To promote education about fi lm, television and the moving image generally, and their impact on society. -

Being Someplace Else: the Theological Virtues in the Anime of Makoto Shinkai

religions Article Being Someplace Else: The Theological Virtues in the Anime of Makoto Shinkai Matthew John Paul Tan School of Philosophy & Theology, University of Notre Dame Australia, Sydney 2008, Australia; [email protected] Received: 28 January 2020; Accepted: 27 February 2020; Published: 2 March 2020 Abstract: This work explores the ways in which the anime of Makoto Shinkai cinematically portrays the theological virtues of faith, hope and love. The article will explore each virtue individually, with specific reference to the work of Josef Pieper and Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI. In addition, it will juxtapose their explorations of these virtues with samples of Shinkai’s corpus of films. It will assert that the consistency of Shinkai’s work reveals several important parallels with the theological virtues. Faith is the encounter between one and another that reveals one’s nature. Hope is revealed by the distance between one and another, and is realised in traversing that distance to achieve an ecstatic reunion. Love, as the erotic attraction between one and another, is the driver that also sustains the journey and closes the distance. In spite of the similarities, important differences between the cinematic and theological will be highlighted. Keywords: anime; virtue; Pieper; Benedict; distance; faith; hope; love 1. Introduction In this work, I focus on the work of the anime director, Makoto Shinkai, who is part of a wave of anime directors rising to prominence after the mainstream success of Hayao Miyazaki. I chose Shinkai for a number of reasons, the first is that with Miyazaki ostensibly going into retirement, Shinkai is now being billed as one of the front-runners for the directors most likely to fill the void in anime that Miyazaki left behind. -

Your Name Screenplay.Fdx

君の名は [Your Name] "Fan-made Screenplay" Original Story and Film by Makoto Shinkai Rewritten in English by Jake Gao gaojake.com [email protected] ii. I want to make it clear that I wrote this with my own time, and without permission from the original filmmakers and producers. As a screenwriting major in Los Angeles, I really wanted to read the screenplay to my favorite movie, Your Name, but I couldn't a copy of it anywhere (Japanese or English). So I came up with the bright idea to write my own! This project was super fun for me as I was able to really study the movie and its details. It also serves as fun writing practice, a way to force myself to write everyday, and something to serve up as a sample of my writing style. I hope that you all enjoy the read, and please feel free to critique me and point out any mistakes-- format, spelling, or grammatical-- as it'll help me improve my future projects! Thank you so much and keep dreaming! -Jake. Original story by Makoto Shinkai 1. EXT. ITOMORI - SKY - NIGHT We are so high sky that sunlight still peaks over the horizon, bouncing off the tops of clouds. Meteorites glow red as they fall towards Earth. Many fragments disintegrate in the atmosphere, but the largest piece dives into the clouds. The sound of wind whistles as the camera tracks the falling comet. The comet bursts through the cloud cover, revealing a darkened prefecture surrounding a large lake. We watch as the comet descends onto Itomori. -

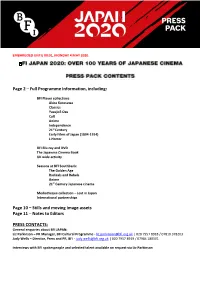

Notes to Editors PRESS

EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01, MONDAY 4 MAY 2020. Page 2 – Full Programme Information, including: BFI Player collections Akira Kurosawa Classics Yasujirō Ozu Cult Anime Independence 21st Century Early Films of Japan (1894-1914) J-Horror BFI Blu-ray and DVD The Japanese Cinema Book UK wide activity Seasons at BFI Southbank: The Golden Age Radicals and Rebels Anime 21st Century Japanese cinema Mediatheque collection – Lost in Japan International partnerships Page 10 – Stills and moving image assets Page 11 – Notes to Editors PRESS CONTACTS: General enquiries about BFI JAPAN: Liz Parkinson – PR Manager, BFI Cultural Programme - [email protected] | 020 7957 8918 / 07810 378203 Judy Wells – Director, Press and PR, BFI - [email protected] | 020 7957 8919 / 07984 180501 Interviews with BFI spokespeople and selected talent available on request via Liz Parkinson FULL PROGRAMME HIGHLIGHTS EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01, MONDAY 4 MAY 2020. BFI PLAYER COLLECTIONS The BFI’s VOD service BFI Player will be the premier destination for Japanese film this year with thematic collections launching over a six month period (May – October): Akira Kurosawa (11 May), Classics (11 May), Yasujirō Ozu (5 June), Cult (3 July), Anime (31 July), Independence (21 August), 21st Century (18 September) and J-Horror (30 October). All the collections will be available to BFI Player subscribers (£4.99 a month), with a 14 day free trial available to new customers. There will also be a major new free collection Early Films of Japan (1894-1914), released on BFI Player on 12 October, featuring material from the BFI National Archive’s significant collection of early films of Japan dating back to 1894. -

A Glimpse in to Japan's History Through Makoto Shinkai'skimi No Nawa

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 24, Issue 10, Series. 11 (October. 2019) 32-37 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org A glimpse in to Japan’s history through Makoto Shinkai’sKimi no nawa (Your Name) Taiyab A. Kapasi Heena apartment, no.4, first floor,Near Fakhri park, Bedipara, Rajkot-36003 Abstract:“Makoto Shinkai could be next big name in anime… a blend of gorgeous,realisticdetails and emotionally grounded fantasy.” (Schilling, Mark) Makoto Shinkai‟sKimi no nawa had broken all the records at box office replacing Hayao Miyazaki‟s „Spirited Away‟as top grossing animated movie in 2016. The movie is about Taki, city boy and Mitsuha, town girl who switches bodies across the time and facing some practical problems which creates comic scenes and leading to a love story. But in the movie a thicker and deeper story is ongoing between the lines. The writer is inspired by natural disaster which shook Japan in 2011. He tries to invoke this incident and raises question about preserving tradition and history of Japan in the movie. The main aim of this paper is to have a glance at history of Japan through Shinkai‟s movie. The paper is divided into two parts, first one consists of brief history of Japan from isolation of Japan to arrival of commodore Matthew Perry, Meiji restoration, triple disaster in 2011and connecting to current era. In second part linear explanation of movie is presented as movie tosses back and forth in time and from Tokyo to Itomori making it complex and hard to grasp. -

A Film Analysis of Makoto Shinkai's Garden of Words, 5Cm Per Second

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-30-2019 A Film Analysis of Makoto Shinkai’s Garden of Words, 5cm per Second, and Your Name AJ Holmberg Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Holmberg, AJ, "A Film Analysis of Makoto Shinkai’s Garden of Words, 5cm per Second, and Your Name" (2019). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 186. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/186 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. A Film Analysis of Makoto Shinkai’s Garden of Words, 5cm per Second, and Your Name Examining Themes of Isolation, Missed Connections, and Passage of Time By Alexander John Holmberg An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Shaun Huston, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director June 2019 Holmberg 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Approach to Research and Terminology 7 Makoto Shinkai’s Filmography & Place in the Industry 16 Garden of Words 20 5cm per Second 32 Your Name 43 Conclusion 53 Works Cited 56 Holmberg 3 Acknowledgements: The completion of this project would not have been possible without my advisor, Dr. Huston, who provided me with the proper resources and timely advice throughout the duration. -

Shinkai Makoto: the “New Miyazaki” Or a New Voice in Cinematic Anime?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Nichibunken Open Access Alistair SWALE Shinkai Makoto: The “New Miyazaki” or a New Voice in Cinematic Anime? Alistair SWALE Shinkai Makoto has steadily consolidated a position as a distinctive and highly innovative animator in contemporary Japan. He has developed a reputation for highly idiosyncratic ‘auteur’ films where he is pivotal in almost every aspect of production—background layouts, character design and plot—and indeed he has been identified by some as the “new Miyazaki”. This paper traces the rise of Shinkai as an animator, examining both the evolution of his distinctive animation techniques and his recurrent concern with fundamental questions of life and nostalgia. The aim is to quite emphatically distinguish Shinkai’s work from Miyazaki, and to discuss how in fact they have rather distinct animation styles and preoccupations. Introduction Shinkai Makoto 新海誠 has emerged as one of the premier auteur animators of the last ten to fifteen years, garnering awards for his largely solo produced works that display a distinctive set of thematics, narrative devices, and visual techniques. Shinkai was born with the original family name, Niitsu, in 1973 in Minamisaku-gun, Nagano Prefecture, into a family who owned a local construction company. He was apparently fond of science fiction from an early age but otherwise followed what might seem to be a relatively conventional path of progression through the education system with incidental involvement in Volleyball and Kyudo which culminated in his entering Chuo University to major in literature in 1991. -

The Circulation of Korean and Japanese Cinema in Spain

141 (DIS)AGREEMENTS BEYOND THE SPORADIC SUCCESSES OF ASIAN FILMS: THE CIRCULATION OF KOREAN AND JAPANESE CINEMA IN SPAIN introduction Antonio Loriguillo-López discussion Quim Crusellas Menene Gras Domingo López José Luis Rebordinos Ángel Sala conclusion Guillermo Martínez-Taberner (DIS)AGREEMENTS introduction ANTONIO LORIGUILLO-LÓPEZ Greeted by audiences and cultural critics alike rent boundaries or restrictions of space and time as the successors to traditional mass media as pro- thanks to universal access to content anywhere viders of audiovisual experiences, digital strea- and anytime (Iordanova, 2012). However, the lo- ming platforms constitute a compelling object of gistical obstacles that can affect any region (from interest. Their emergence as heirs to the home bandwidth speed and coverage to content access audiovisual market has also been studied as a key restrictions arising from licensing conflicts) pose to understanding the manifest tension between issues that remind us that this supposed ubiquity the “global” and the “local” in an increasingly di- is always dependent on contextual factors (Evans, gitalised media context. The use of the internet Coughlan & Coughlan, 2017). by the audiovisual industry as a distribution pla- The promises of access anytime from anywhe- tform has resulted in a complex relationship be- re that underpin the rhetoric of its promoters and tween infrastructures and services that allow film defenders thus need to be contrasted against the and television distributors and consumers to cast irrefutable reality -

Opens in Cinemas in the UK and Ireland from 2Nd November 2018

MIRAI Opens in cinemas in the UK and Ireland from 2nd November 2018 Starring MOKA KAMISHIRAISHI, HARU KUROKI, GEN HOSHINO, KUMIKO ASO and MITSUO YOSHIHARA Directed by Mamoru Hosoda Run Time: 98 minutes Press Contacts: Lisa DeBell - [email protected] Almar Haflidason - [email protected] MIRAI Ingenious and heartfelt, Mamoru Hosoda’s charming fantasy was the first Japanese anime to have its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, where it received a standing ovation. The truest definition of a family film, “Mirai” will inspire the imaginations of young and old alike. MIRAI is the most personal journey yet for director Mamoru Hosoda, whose renown rivals even that of Hayao Miyazaki (“Spirited Away”) and Makoto Shinkai (“Your Name”). Having recently become a parent, Mamoru Hosoda draws inspiration from his own family to tell a tale from the unique worldview of a toddler. Intertwining an endearing yet honest portrayal of childhood with wondrous fantasy spectacle, “Mirai” is a triumphant example of the imaginative yet human stories made possible through the medium of anime. Children are sure to delight in Kun’s animated personality, whilst parents will find comfort in how true to life the cast is - time-travelling notwithstanding! Like Makoto Shinkai’s “Your Name”, Mamoru Hosoda sheds new light on a thematic thread weaved through his other standalone films, exploring another key family dynamic - the bond between brother and sister. Even the film’s stage is inspired by its pint-sized protagonist, with the story largely playing out in the few environments known to a four-year old: the home and garden. -

Research Material Anime Bfi Japan a Quick History of Anime

RESEARCH MATERIAL ANIME BFI JAPAN A QUICK HISTORY OF ANIME Early 20th century - 1950s Image from The Tale of the White Serpent (Hakujaden), Kazuhiko Okabe and Taiji Yabushita, 1958 Beginning of animation in Japan and professional animators but most of the works and infrastructures were destroyed by the 1923 earthquake. Today, short animes from the 1930s can still be found. Like most silent Japanese movies, these films made use of a benshi. In 1958, The Tale of the White Serpent (also known as Panda and the Magic Serpent) is the first colour anime feature film to be released. Produced by Toei Animation, the film is clearly inspired by the work of Walt Disney: after WWII and the Allied occupation, Japan is exposed to American animation. It will be the beginning of decades of revolutionnary Japanese anime. A restored version has been screened this year at the Cannes Film Festival. Films: • Namakura Gatana (Blunt Sword), 1917: oldest surviving example of Japanese animation • Ugokie Kori no Tatehiki, Ikuo Oishi, 1931 • The Tale of the White Serpent, (Hakujaden), Kazuhiko Okabe and Taiji Yabushita, 1958 @FilmHubMidlands [email protected] The 1960s Astro Boy, created by Osamu Tezuka, 1963 The 1960s brought anime to televIsion and in America. In 1963, the first episode ofAstro Boy is released on Japanese television. The show created by Osamu Tezuka (called “the god of Manga”) is a hit and change the anime industry: Astro Boy was highly influential to other anime in the 1960s, and was followed by a large number of anime about robots or space. Films and TV Shows: • Astro Boy, directed by Osamu Tezuka and produced by Mushi Production, 1963 • Sally the Witch, produced by Toei Animation, 1966: first anime magical girls, one of the first Shōjo (manga for young girls) Important names: • Mushi Production • Toei Animation • Osamu Tezuka @FilmHubMidlands [email protected] The 1970s Heidi created by Isao Takahata, 1974 The Mangas (comic books) grew in popularity, many of which were animated later.