COASTS, ESTUARIES and TIDAL HYDRAULICS Ion Super- J

Total Page:16

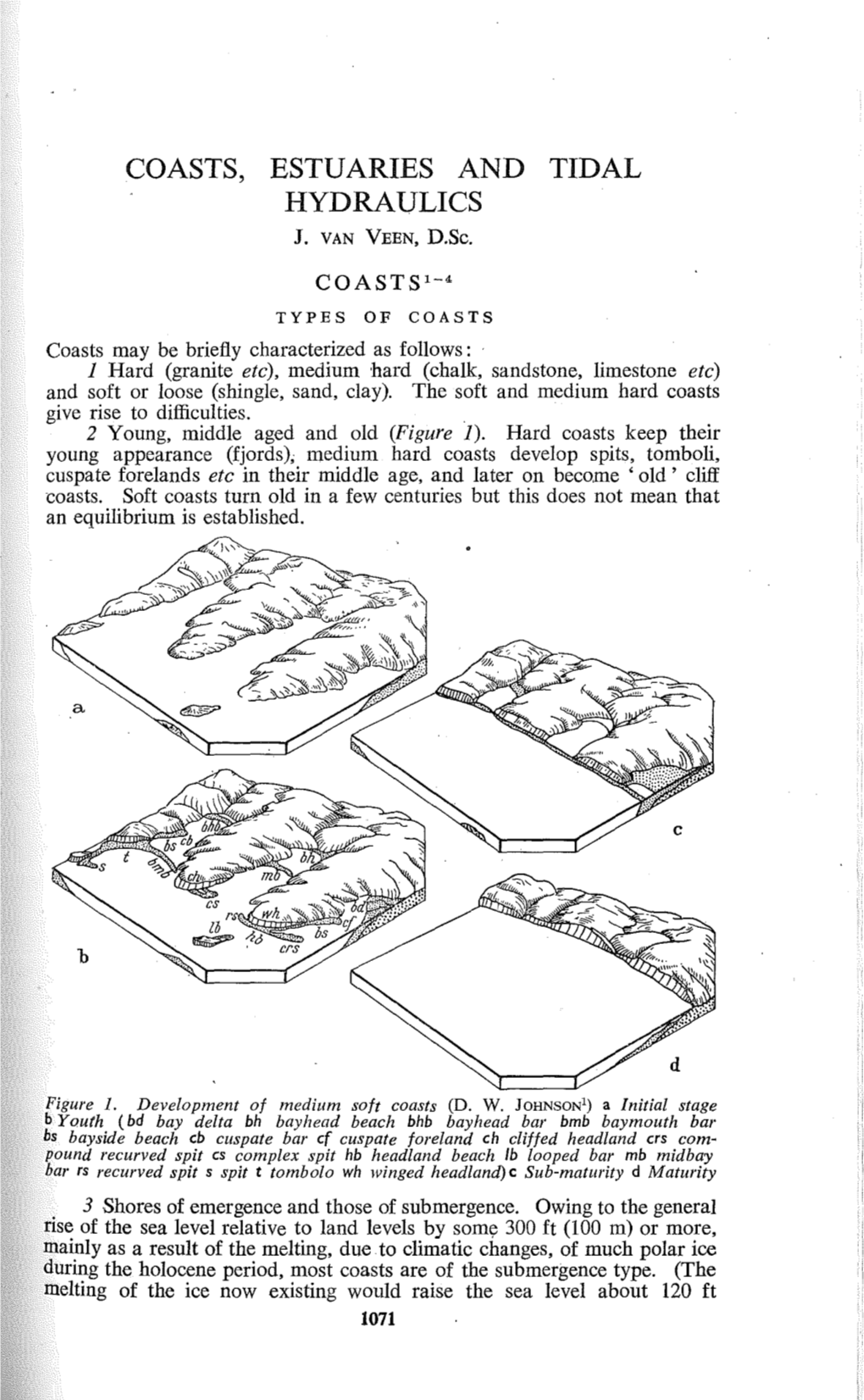

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of Glacial & Coastal Landforms

1 GEOMORPHOLOGY 201 READER PART IV : EVOLUTION OF GLACIAL & COASTAL LANDFORMS A landform is a small to medium tract or parcel of the earth’s surface. After weathering processes have had their actions on the earth materials making up the surface of the earth, the geomorphic agents like running water, ground water, wind, glaciers, waves perform erosion. The previous sections covered the erosion and deposition and hence landforms caused by running water (fluvial geomorphology) and by wind (aeolian geomorphology). Erosion causes changes on the surface of the earth and is followed by deposition, which likewise causes changes to occur on the surface of the earth. Several related landforms together make up landscapes, thereby forming large tracts of the surface of the earth. Each landform has its own physical shape, size, materials and is a result of the action of certain geomorphic processes and agents. Actions of most of the geomorphic processes and agents are slow, and hence the results take a long time to take shape. Every landform has a beginning. Landforms once formed may change their shape, size and nature slowly or fast due to continued action of geomorphic processes and agents. Due to changes in climatic conditions and vertical or horizontal movements of landmasses, either the intensity of processes or the processes themselves might change leading to new modifications in the landforms. Evolution here implies stages of transformation of either a part of the earth’s surface from one landform into another or transformation of individual landforms after they are once formed. That means, each and every landform has a history of development and changes through time. -

An International Journal Published by the Marine Environmental Alabama Sciences Consortium Of

An International Journal Evolution of the Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory MICHAEL J. GREENBERG,WILLIAM F. HERRNKIND, AND FELICIA C. COLEMAN Published by the Marine Environmental Sciences Consortium of Alabama Gulf of Mexico Science, 2010(1–2), pp. 149–163 Evolution of the Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory MICHAEL J. GREENBERG,WILLIAM F. HERRNKIND, AND FELICIA C. COLEMAN SIXTY YEARS OF HISTORY and the toponym Turkey Point Laboratory or, more often, the FSU Marine Laboratory n 1949, just 2 yr after the Florida State College (FSUML) stuck for more than 4 decades. I for Women was transformed into a coeduca- In 2006, Felicia Coleman became the 13th tional institution—The Florida State University director of the Laboratory. She is the first (FSU)—marine science gained a permanent director whose primary workplace is at the foothold on the Tallahassee campus with the laboratory, and the first with an on-site faculty formation of The Oceanographic Institute (OI). to manage. And the laboratory became the FSU This institute—within the College of Arts and Coastal and Marine Laboratory (FSUCML). Sciences—was meant to train graduate students The history of these two laboratories, which in marine science, to provide marine research follows, is narrated primarily by three of the 13 facilities for faculty and students and visiting directors. We have divided the narrative into four investigators, to conduct interdisciplinary basic distinct periods: The Genesis, 15 yr at Alligator research in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico, and Harbor; The Great Move from Alligator Harbor also to conduct applied research directed toward to Turkey Point, 7 yr of change; The Long improving Florida’s fishing industry and devel- Struggle at Turkey Point, 34 yr of intermittent, oping other marine resources. -

Oce1001, Introduction to Oceanography, Fall, 2005

OCE1001, INTRODUCTION TO OCEANOGRAPHY, Fall, 2018 THIRD MID-TERM EXAMINATION Test No. 0001 Name: __________________________ READ THIS!!!! Put your name in the blank above. Read all questions carefully, and answer only the question which is asked. You may find the following equations useful: C = (gL/2) = 1.25 L (m/s) Where: C = speed of a wave and: g = gravity = 9.8 m/s2 C = (gD) = 3.1 D (m/s) L = wavelength of a wave C = 1.56 T (m/s) D = water depth C = L/T T = period of a wave PLEASE WRITE NEATLY. Matching: The Beaches Are Moving (8 pts) Do not put these on the scantron sheet. ____ neap ____ hook A. worldwide change in sea level. B. structure intended to widen a beach. ____ jetty ____ groin C. wall intended to keep a channel open. D. two high and two low tides per day. ____ eustatic E. current parallel to the shore caused by waves. ____ semidiurnal F. twice monthly tide that with a smaller than average range. ____ marine terrace G. bend in end of a spit caused by wave refraction. ____ longshore current H. region eroded flat by waves, elevated above sea level. ____ longitudinal I. disturbance of wave is parallel to wave movement Multiple Choice: (2 pts each) Put the answers to these questions on the scantron sheet. 1. In Figure 1, the features labeled 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 are, respectively: a. spit, barrier island, baymouth bar, hook, tombolo. b. hook, spit, baymouth bar, barrier island, tombolo. c. tombolo, spit, baymouth bar, barrier island, hook. -

174 Coastal Processes and Hazards I. WATER, WAVES and COASTAL

Coastal Processes and Hazards I. WATER, WAVES AND COASTAL DYNAMICS A. Beach and coastal areas represent sites of dynamic sedimentation, erosion and re- working of river-borne sediments as they reach coastal regions 1. Dynamic interaction between wind, waves, sedimentation and erosion 2. Coastal areas noted for extremely variable meteorologic conditions 3. Hurricanes and storms profoundly influence coastal morphology a. Wave energy and wind energy during coastal storms exhibit great capability to do work in the form of erosion and transportation of sediment (1) Eg. storm wash-over processes (2) storm surges (3) changes in coastal morphology via erosion and sedimentation 4. Gross coastal configuration primarily a function of plate tectonic history, however relentless wave processes modify coast through erosion and sedimentation B. The Ocean and Wave Activity 1. Beach/coastal sand/sediment profoundly influenced by wave action a. waves provide motion/energy for transportation and erosion of sediment 2. Waves generated by wind shear blowing across ocean surface for long distances a. shear creates orbital rotation of water to form water waves (1) orbital motion = circular to and fro motion, diminishing in intensity at depth from surface (2) Although the wave is passed through the water as a medium; actual water molecules are NOT displaced as the wave is propagated b. Wave form controlled by: (1) wind velocity (2) duration of wind (3) fetch- distance over which wind blows (length across water) (> fetch, > wave amplitude) 3. Wave Morphology a. Wave crest: high upper peak of wave train b. Wave trough: low separating two crests c. Wave Height: vertical distance between crest and trough (1) Avg. -

Shoreline Changes in the Isles Dernieres Barrier Island Arc: 1887-1996 Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana

SHORELINE CHANGES IN THE ISLES DERNIERES BARRIER ISLAND ARC: 1887-1996 TERREBONNE PARISH, LOUISIANA Shea Penland11, Chris Zganjar22, Karen A. Westphal2, Paul Connor1 Jeff List3 and S. Jeffress Williams3 INTRODUCTION The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), in cooperation with the Coastal Research Laboratory in the Department of Geology and Geophysics at the University of New Orleans (UNO) and the Center for Coastal Energy and Environmental Resources at Louisiana State University (LSU), is investigating the processes of coastal erosion and wetland loss in Louisiana (Sallenger and others, 1987; Sallenger and Williams 1989; Penland and others, 1992). Building on the USGS Louisiana Barrier Island Study (Williams and others, 1992) and the USGS Hurricane Andrew impact assessment (Penland and others, 1998), this USGS Open-File Report depicts shoreline changes between 1887 and 1996, which provides an 8-year update of McBride and others (1992). The Isles Dernieres are located about 120 km southwest of New Orleans (Figure 1). This barrier island shoreline is 32 km long and extends from Caillou Bayou east to Wine Island Pass. The Isles Dernieres represent a barrier island arc developed from the reworking and erosion of an abandoned distributary of the Lafourche delta complex within the Mississippi River delta plain (Penland and others, 1988). Previous work by McBride and others (1992) documented a long-term (1887-1988) gulfside erosion rate of -11.1 m/yr and a short-term (1978-1988) gulfside erosion rate of -19.2 m/yr. The long- term bayside (1906-1988) erosion rate was measured at -0.6 m/yr and the short-term (1978-1988) bayside erosion rate was measured at -5.2 m/yr. -

Deposition Sites Erosional and Depositional Ar1n Counties

U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Prepared in cooperation with the DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING DEVELOPMENT Deposition Sites Erosional and Depositional ar1n• Counties, California 1974 Pamphlet to accompany Miscellaneous Fi~ld Studies Map MF-625 Jointly supported by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Department of Housing and Urban Development as part of a program to develop earth-science information in a form applicable to land-use planning and decision making. Pamphlet text to accompany MF-625 SEDIMENT SOURCE AND DEPOSITION SITES AND EROSIONAL AND DEPOSITIONAL PROVINCES MARIN AND SONOMA COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA By William M. Brown III and Lionel E. Jackson, Jr. INTRODUCTION The land surface of Marin and Sonoma Counties is a precise recorder of the natural and artificial factors that have shaped it. It is also an excellent predictor of the forms it will probably have in the future, given an estimate of the human and natural factors expected to act upon it. Studying the land surface for clues about its past and future, therefore, is a necessary aspect of thorough land-use planning and decisionmaking about land-use designs. This report is intended to aid the planner and decisionmaker in studying the land surface of Marin and Sonoma Counties. It is primarily concerned w~th the erosion, transportation, and deposition of sediment as a process that alters the land surface. It attempts to explain what sediment is, where sediment comes from, and where sediment goes. This report also describes how and why sediment moves from one point to another and for areas where data are available describes rates and quantities of sediment movement. -

A Data Compilation and Assessment of Coastal Wetlands of Wisconsin's Great Lakes Final Report

A Data Compilation and Assessment of Coastal Wetlands of Wisconsin’s Great Lakes Final Report Authors Eric Epstein, Elizabeth Spencer, Drew Feldkirchner Contributors Craig Anderson, Julie Bleser, Andy Clark, Emmet Judziewicz, Nicole Merryfield, Andy Paulios, Bill Smith Natural Heritage Inventory Program Bureau of Endangered Resources Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources P.O. Box 7921 Madison WI 53707-7921 PUBL ER-803 2002 Copies of this report can be obtained by writing to the Bureau of Endangered Resources at the above address. This publication is available in alternative format (large print, Braille, audiotape, etc) upon request. Please call (608-266-7012) for more information. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources provides equal opportunity in its employment, programs, services, and functions under an Affirmative Action Plan. If you have any questions, please write to Equal Opportunity Office, Department of Interior, Washington, D.C. 20240. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Funding for this project was provided by the Wisconsin Coastal Zone Management Program. This support is gratefully acknowledged with special thanks to Travis Olson, Department of Administration. A number of individuals conducted inventory work and provided support to complete this project. We would like to extend our thanks to those persons listed below for their assistance. We would also like to extend our appreciation to the private landowners who granted us permission to work on or cross their properties. Data Management/GIS/Graphics Development: Julie Bleser, Natural -

Great Lakes Shore Fen (Global Rank NA; State Rank S2)

Great Lakes Shore Fen (Global Rank NA; State Rank S2) Overview: Distribution, Abundance, !( !( !(!( !( !( Environmental Setting, Ecological Processes !( The Great Lakes Shore Fen is a circumneutral, moderately minerotrophic, open peatland community of intermediate richness that is an integral part of the diverse vegetation mosaics of estuaries and lagoons at sites along Lake Superior in northwestern Wisconsin and at several protected Lake Michigan embayments on the margins of the Door Peninsula. On Lake Superior, the Great Lakes Shore Fens are often !( partially protected from wind, wave, and ice disturbance by a sandspit. On Lake Michigan, horizontal exposures of dolo- mite bedrock, which sometimes extend well out into the lake, may serve a similar function. Many of the documented occurrences are within estuarine wetland complexes that develop at drowned river mouths, especially along Lake Superior’s southwestern shore. Other examples occur in the complex community mosaics associ- ated with Great Lakes coastal lagoons, such as those on Stock- ton, Outer, and Michigan islands in the Apostles Archipelago. Along Lake Superior’s southwestern shore, drowned river mouths are common features because of the geological phe- nomenon referred to as differential isostatic rebound (Lee and Southan 1994). Wetlands along eastern Lake Superior are Locations of Great Lakes Shore Fen in Wisconsin. The deeper hues becoming more separated from the lake as the land rebounds shading the ecological landscape polygons indicate geographic areas of greatest abundance. An absence of color indicates that the from the historical weight of the glacial ice, while lands on the community has not (yet) been documented in that ecological land- western end of the lake—including the coastal wetlands—are scape. -

Checklist of Free–Living Nematode Species in the Transitional Environment of Lake Varano (Southern Italy)

Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica, 13 (2015): 32–46 SemprucciISSN: 1698& Balsamo–0476 Checklist of free–living nematode species in the transitional environment of Lake Varano (Southern Italy) F. Semprucci & M. Balsamo Semprucci, F. & Balsamo, M., 2015. Chec�������list o� ����������������������������������������ree–living nematode species in the tran� sitional environment o� La�e Varano (Southern Italy). Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica, 13: 32–46. Abstract Checklist of free–living nematode species in the transitional environment of Lake Varano (Southern Italy).— This study documents �or the first time the taxonomic composition �o the nematode community and the number o� �ree–living nematode species in La�e Varano, Southern Adriatic Sea, Italy. The nematode community was mainly composed o� species typical o� fine sediments that usually prevail in transitional environments (TEs). An overall high number o� nematode species was recorded (55), belonging to 36 genera in 17 �amilies. These values are highly comparable to those reported �or other Italian TEs, but appear lower than those recorded in other European brac�ish–water systems, probably in relation to the low salinity range o� La�e Varano. Forty taxa were identified up to species level, thus increasing the number �o the nematode marine species �nown �or the Italian coasts �rom 443 to 463, �or the Adriatic basin �rom 310 to 313, and �or the Southern Adriatic sector �rom 37 to 77. Considering the impor� tance o� this phylum in the assessment o� ecological quality and the great vulnerability o� the Adriatic Sea ecosystems, an intensification �o sampling efforts should be planned, especially in the Central–Southern part o� the basin. -

Lake Superior National Estuarine Research Reserve LAKE SUPERIOR NATIONAL ESTUARINE RESEARCH RESERVE MANAGEMENT PLAN

ManageMent Plan 2010 - 2015 Lake Superior National estuarine research reserve LAKE SUPERIOR NATIONAL ESTUARINE RESEARCH RESERVE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2010-2015 Prepared by: University of Wisconsin-Extension September 2010 Prepared for: U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management Estuarine Reserves Division 1305 East West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910 University of Wisconsin - Extension 432 North Lake Street Madison, WI 53706 This Management Plan has been developed in accordance with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) regulations, including all provisions for public involvement. It is consistent with the congressional intent of Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, and the provisions of the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program. This publication is funded, in part, through a grant agreement with the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA08NOS4200405. Cover photography by: Michael K. Anderson Interior photography by: Amy Elliot, Becky Sapper, Michael K. Anderson, Patrick Robinson, Lynelle Hanson and Frank Koshere - WDNR Graphic Design by: Amy B. Torrey - UW Extension Lake Superior NatioNaL EstuariNe RESEARCH RESERVe 2010-2015 i | Table of Contents Table of Contents LIST OF APPENDICES iii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF MAPS iv LIST OF TABLES iv LIST OF ACRONYMS v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 6 Purpose and Scope of the Lake Superior NERR Management Plan. 6 Description of the Lake Superior NERR. 7 Great Lakes Freshwater Estuaries. 7 Lake Superior NERR Key Attributes and Setting. -

Shoreline Processes: Overview of Waves the Ocean's Surfa

page - Laboratory Exercise #5 – Shoreline Processes Section A – Shoreline Processes: Overview of Waves The ocean’s surface is influenced by three types of motion (waves, tides and surface currents). Shorelines dominated by wave action comprise approximately 80% of the coastlines on earth and will be the focus of today’s laboratory exercise. Tidal action is dominant in 17% of the earth’s shorelines with surface ocean currents (such as the Gulf Stream) dominating only 3% of shorelines. The anatomy of a wave includes the crest or highest point on a wave and the trough, which is the lowest point on a wave (Figure 1). The vertical distance between the crest and trough is referred to as the wave height. Additional important concepts include the wavelength, which is the distance between two successive crests. The wave base is the water depth below which no energy is felt by the passage of a wave. Note that the orbitals reflecting the movement below a wave are circular. Also, these orbitals become progressively smaller with greater depths until they disappear. The depth at which the orbitals disappear and where the water is no longer being moved by the wave is the wave base. There is a simple mathematical relationship that defines wave base. Wave base = 1 / 2 of wavelength For example, a typical fair weather wave has a wavelength of 60 feet. This wave will have a wave base of 30 feet. The shape of the orbitals below the wave in Figure 1 is circular. This type of wave is a wave of oscillation and occurs offshore. -

Physical Geology Shorelines

Physical Geology Shorelines Multiple Guess: (You know the drill – 2 points each) 1. The path of movement of a water particle in a wave at sea is 1. circular 2. horizontal 3. vertical 4. elliptical 5. none of these answers 2. Waves of oscillation transport 1. water 2. energy 3. floating matter 4. sediment 5. All of the above 3. Which of the following statements is NOT a true description of ocean waves? 1. Waves originate by the frictional action of wind on water. 2. Energy is imparted to waves by winds. 3. Water particles in waves move along at the same velocity as the wave. 4. Wave height is the vertical distance between crest and trough. 5. Wave refraction causes irregular distribution of energy along the coast. 4. When waves reach shallow water they become 1. shorter and higher 2. longer and lower 3. longer and higher 4. shorter and lower 5. remain unchanged in form 5. On an irregular shoreline, the energy of a wave is 1. concentrated mostly on the headlands by wave refraction 2. dissipated at the line where the wave first "feels bottom" 3. evenly spread over the entire shoreline 4. usually completely dissipated before reaching the shore 5. concentrated along the beaches by wave refraction 6. Which of the following conditions would generate a longshore current? 1. rip currents 2. a tsunami 3. waves parallel to the shore 4. a spring tide 5. waves striking the beach at an oblique angle 7. Which of the following is the most likely trend in the evolution of coastal features? 1.