04. Ecological Relationships Lesson #3: CLARK THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

There's No Place Like Home

United States Department of Agriculture There’s No Place Like Home: D E E Forest Service P R A R U TM U LT ENT OF AGRIC Pacific Northwest Region Clark’s Nutcracker Home Ranges and 2011 Whitebark Pine Regeneration FOR CLARK’S nutcrackers, “home” is a year-round hub. What do we mean by “space use” and “home range”? Although nutcrackers show tenacious fidelity to home ranges in winter, spring, and summer, they spend every “Space use” describes how animals use a landscape. The term autumn traveling around to harvest seeds. Nearly all seeds is most commonly used to discuss home range characteristics are transported back home for storage, a process that has and the selection of resources (habitats, food items, roost sites) vast implications for forest regeneration. within home ranges. In our study, we used the term “home range” to describe the BACKGROUND area used by a resident nutcracker for all year-round activities We investigated habitat use, caching behavior, and except seed harvest. This is because areas used for seed harvest migratory patterns in Clark’s nutcrackers in the Pacific in autumn were ever-changing and temporary—birds showed Northwest using radio telemetry. Over 4 years (2006– no fidelity to forests used for seed harvest, but rather used these 2009), we captured 54 adult nutcrackers at 10 sites in the forests only as long as seeds were present on trees. Cascade and Olympic Mountains in Washington State. What do we know about nutcracker space use? We fitted nutcrackers with a back-pack style harness. The battery life on the radio tags was 450 days, and Vander Wall and Balda (1977) and Tomback (1978) were the we tracked nutcrackers year-round, on foot (to obtain first to report that nutcrackers harvest large-seeded pines in behavior observations) and via aircraft (to obtain point autumn and often range over large areas and multiple elevation locations). -

The Perplexing Pinyon Jay

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Behavior and Biological Sciences Papers in the Biological Sciences 1998 The Ecology and Evolution of Spatial Memory in Corvids of the Southwestern USA: The Perplexing Pinyon Jay Russell P. Balda Northern Arizona University,, [email protected] Alan Kamil University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscibehavior Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons Balda, Russell P. and Kamil, Alan, "The Ecology and Evolution of Spatial Memory in Corvids of the Southwestern USA: The Perplexing Pinyon Jay" (1998). Papers in Behavior and Biological Sciences. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscibehavior/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Behavior and Biological Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published (as Chapter 2) in Animal Cognition in Nature: The Convergence of Psychology and Biology in Laboratory and Field, edited by Russell P. Balda, Irene M. Pepperberg, and Alan C. Kamil, San Diego (Academic Press, 1998), pp. 29–64. Copyright © 1998 by Academic Press. Used by permission. The Ecology and Evolution of Spatial Memory in Corvids of the Southwestern USA: The Perplexing Pinyon Jay Russell P. Balda 1 and Alan C. Kamil 2 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Northern -

Walker Marzluff 2017 Recreation Changes Lanscape Use of Corvids

Recreation changes the use of a wild landscape by corvids Author(s): Lauren E. Walker and John M. Marzluff Source: The Condor, 117(2):262-283. Published By: Cooper Ornithological Society https://doi.org/10.1650/CONDOR-14-169.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1650/CONDOR-14-169.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Volume 117, 2015, pp. 262–283 DOI: 10.1650/CONDOR-14-169.1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Recreation changes the use of a wild landscape by corvids Lauren E. Walker* and John M. Marzluff College of the Environment, School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA * Corresponding author: [email protected] Submitted October 24, 2014; Accepted February 13, 2015; Published May 6, 2015 ABSTRACT As urban areas have grown in population, use of nearby natural areas for outdoor recreation has also increased, potentially influencing bird distribution in landscapes managed for conservation. -

Individual Repeatability, Species Differences, and The

Supplementary Materials: Individual repeatability, species differences, and the influence of socio-ecological factors on neophobia in 10 corvid species SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS 2 Figure S1 . Latency to touch familiar food in each round, across all conditions and species. Round 3 differs from round 1 and 2, while round 1 and 2 do not differ from each other. Points represent individuals, lines represent median. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS 3 Figure S2 . Site effect on latency to touch familiar food in azure-winged magpie, carrion crow and pinyon jay. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS 4 Table S1 Pairwise comparisons of latency data between species Estimate Standard error z p-value Blue jay - Azure-winged magpie 0.491 0.209 2.351 0.019 Carrion crow - Azure-winged magpie -0.496 0.177 -2.811 0.005 Clark’s nutcracker - Azure-winged magpie 0.518 0.203 2.558 0.011 Common raven - Azure-winged magpie -0.437 0.183 -2.392 0.017 Eurasian jay - Azure-winged magpie 0.284 0.166 1.710 0.087 ’Alal¯a- Azure-winged magpie 0.416 0.144 2.891 0.004 Large-billed crow - Azure-winged magpie 0.668 0.189 3.540 0.000 New Caledonian crow - Azure-winged magpie -0.316 0.209 -1.513 0.130 Pinyon jay - Azure-winged magpie 0.118 0.170 0.693 0.488 Carrion crow - Blue jay -0.988 0.199 -4.959 0.000 Clark’s nutcracker - Blue jay 0.027 0.223 0.122 0.903 Common raven - Blue jay -0.929 0.205 -4.537 0.000 Eurasian jay - Blue jay -0.207 0.190 -1.091 0.275 ’Alal¯a- Blue jay -0.076 0.171 -0.443 0.658 Large-billed crow - Blue jay 0.177 0.210 0.843 0.399 New Caledonian crow - Blue jay -0.808 0.228 -3.536 -

Zoologische Verhandelingen

Systematic notes on Asian birds. 45. Types of the Corvidae E.C. Dickinson, R.W.R.J. Dekker, S. Eck & S. Somadikarta With contributions by M. Kalyakin, V. Loskot, H. Morioka, C. Violani, C. Voisin & J-F. Voisin Dickinson, E.C., R.W.R.J. Dekker, S. Eck & S. Somadikarta. Systematic notes on Asian birds. 45. Types of the Corvidae. Zool. Verh. Leiden 350, 26.xi.2004: 111-148.— ISSN 0024-1652/ISBN 90-73239-95-8. Edward C. Dickinson, c/o The Trust for Oriental Ornithology, Flat 3, Bolsover Court, 19 Bolsover Road, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN20 7JG, U.K. (e-mail: [email protected]). René W.R.J. Dekker, National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands (e-mail: [email protected]). Siegfried Eck, Staatliche Naturhistorische Sammlungen Dresden, Museum für Tierkunde, A.B. Meyer Bau, Königsbrücker Landstrasse 159, D-01109 Dresden, Germany (e-mail: [email protected]. sachsen.de). Soekarja Somadikarta, Dept. of Biology, Faculty of Science and Mathematics, University of Indonesia, Depok Campus, Depok 16424, Indonesia (e-mail: [email protected]). Mikhail V. Kalyakin, Zoological Museum, Moscow State University, Bol’shaya Nikitskaya Str. 6, Moscow, 103009, Russia (e-mail: [email protected]). Vladimir M. Loskot, Department of Ornithology, Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Science, St. Petersburg, 199034 Russia (e-mail: [email protected]). Hiroyuki Morioka, Curator Emeritus, National Science Museum, Hyakunin-cho 3-23-1, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 100, Japan. Carlo Violani, Department of Biology, University of Pavia, Piazza Botta 9, 27100 Pavia, Italy (e-mail: [email protected]). -

Clark's Nutcracker (Nucifraga Columbiana)

PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF THREE HIGH LATITUDE RESIDENT CORVIDS: CLARK’S NUTCRACKER (NUCIFRAGA COLUMBIANA), EURASIAN NUTCRACKER (NUCIFRAGA CARYOCATACTES), AND GRAY JAY (PERISOREUS CANADENSIS) KIMBERLY MARGARET DOHMS Bachelor of Science Honours, University of Regina, 2001 Masters of Science, University of Regina, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Biological Sciences University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Kimberly M. Dohms, 2016 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF THREE HIGH LATITUDE RESIDENT CORVIDS: CLARK’S NUTCRACKER (NUCIFRAGA COLUMBIANA), EURASIAN NUTCRACKER (NUCIFRAGA CARYOCATACTES), AND GRAY JAY (PERISOREUS CANADENSIS) KIMBERLY MARGARET DOHMS Date of Defense: November 30, 2015 Dr. T. Burg Associate Professor Ph.D Supervisor Dr. A. Iwaniuk Associate Professor Ph.D Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. C. Goater Professor Ph.D Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. D. Logue Assistant Professor Ph.D Internal Examiner Dr. K. Omland Professor Ph.D External Examiner University of Maryland, Baltimore County Baltimore, Maryland Dr. J. Thomas Professor Ph.D Chair, Thesis Examination Committee DEDICATION For the owl and the pussy cat. (And also the centipede.) iii GENERAL ABSTRACT High latitude resident bird species provide an unique opportunity to investigate patterns of postglacial and barrier-mediated dispersal. In this study, multiple genetic markers were used to understand postglacial colonization by and contemporary barriers to gene flow in three corvids. Clark’s nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana), Eurasian nutcracker (N. caryocatactes), and gray jay (Perisoreus canadensis) are year-round resident northern hemisphere passerines with ranges encompassing previously glaciated and unglaciated regions and potential barriers to dispersal (e.g. -

British Birds |

VOL. LI DECEMBER No. 12 1958 BRITISH BIRDS CONCEALMENT AND RECOVERY OF FOOD BY BIRDS, WITH SOME RELEVANT OBSERVATIONS ON SQUIRRELS By T. J. RICHARDS THE FOOD-STORING INSTINCT occurs in a variety of creatures, from insects to Man. The best-known examples are found in certain Hymenoptera (bees, ants) and in rodents (rats, mice, squirrels). In birds food-hoarding- has become associated mainly with the highly-intelligent Corvidae, some of which have also acquired a reputation for carrying away and hiding inedible objects. That the habit is practised to a great extent by certain small birds is less generally known. There is one familiar example, the Red- backed Shrike (Lanius cristatus collurio), but this bird's "larder" does not fall into quite the same category as the type of food- storage with which this paper is concerned. Firstly, the food is not concealed and therefore no problem arises regarding its recovery, and secondly, since the bird is a summer-resident, the store cannot serve the purpose of providing for the winter months. In the early autumn of 1948, concealment of food by Coal Tit (Parns ater), Marsh Tit (P. palustris) and Nuthatch (Sitta enropaea) was observed at Sidmouth, Devon (Richards, 1949). Subsequent observation has confirmed that the habit is common in these species and has also shown that the Rook (Corvus jrngilegus) will bury acorns [Querents spp.) in the ground, some- • times transporting the food to a considerable distance before doing so. This paper is mainly concerned with the food-storing behaviour of these four species, and is a summary of observations made intermittently between 1948 and 1957 in the vicinity of Sidmouth. -

Testing Two Competing Hypotheses for Eurasian Jays' Caching for the Future

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Testing two competing hypotheses for Eurasian jays’ caching for the future Piero Amodio1,2,6*, Johanni Brea3,6, Benjamin G. Farrar1,4, Ljerka Ostojić1,4,5 & Nicola S. Clayton1 Previous research reported that corvids preferentially cache food in a location where no food will be available or cache more of a specifc food in a location where this food will not be available. Here, we consider possible explanations for these prospective caching behaviours and directly compare two competing hypotheses. The Compensatory Caching Hypothesis suggests that birds learn to cache more of a particular food in places where that food was less frequently available in the past. In contrast, the Future Planning Hypothesis suggests that birds recall the ‘what–when–where’ features of specifc past events to predict the future availability of food. We designed a protocol in which the two hypotheses predict diferent caching patterns across diferent caching locations such that the two explanations can be disambiguated. We formalised the hypotheses in a Bayesian model comparison and tested this protocol in two experiments with one of the previously tested species, namely Eurasian jays. Consistently across the two experiments, the observed caching pattern did not support either hypothesis; rather it was best explained by a uniform distribution of caches over the diferent caching locations. Future research is needed to gain more insight into the cognitive mechanism underpinning corvids’ caching for the future. Over the last two decades, an increasing number of studies in non-human animals have challenged the view that future planning abilities are uniquely human (primates:1–5; corvids:6–9; rodents:10,11, although see2). -

P0449-P0451.Pdf

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 449 aspects of temperature regulation in the Burrow- ical contamination in golden eagles in south- ing Owl, Speotyto cunicularia. Camp. Biochem. western Idaho. MS. thesis. Univ. of Idaho. Physiol. 35: 307-337. Moscow, Idaho. FITCH, H. S. 1974. Observations on the food and NELSON, M. 1969. Status of the peregrine falcon in nesting of the Broad-winged Hawk (Buteo the northwest, p. 64-72. In J. J. Hickey [ed.], platypterus) in northern Kansas. Condor 76: Peregrine Falcon populations, their biology and 331-333. decline. Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison, FITCH, H. S., F. SWENSON AND D. F. TILLOTSON. Wisconsin. 1946. Behavior and food habits of the Red- SOUTHWICK, E. E. 1973. Remote sensing of body tailed Hawk. Condor 48:205-237. temperature in a captive 25-G bird. Condor GATEHOUSE, S. N. AND B. J. MARKHAM. 1970. 75 :464-466. Respiratory metabolism of three species of rap- WARHAM, J. 1971. Body temperatures of petrels. tors. Auk 87:738-741. Condor 73:214-219. HATCH, D. E. 1970. Energy conservation and heat dissipating mechanisms of the Turkey Vulture. Department of Biology, Northwest Nazarene College, Auk 87:111-124. Nampa, Idaho 83651. Accepted for publication 26 KOCHERT, M. N. 1972. Population status and chem- February 1978. Cudor, 80:449-451 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1978 PREDATION ON VERTEBRATES times (Table 1). At least six attacks were successful; BY CLARKS’ NUTCRACKERS on the other occasions, the prey escaped by entering a burrow or bush. Beldings’ Ground Squirrels were attacked most BARRY S. MULDER frequently ( 54% ), but because our observations BRIAN B. -

Apparent Predation by Gray Jays, Perisoreus Canadensis, on Long-Toed Salamanders, Ambystoma Macrodactylum, in the Oregon Cascade Range

Notes Apparent Predation by Gray Jays, Perisoreus canadensis, on Long-toed Salamanders, Ambystoma macrodactylum, in the Oregon Cascade Range MICHAEL P. M URRAY1,CHRISTOPHER A. PEARL2, and R. BRUCE BURY2 1 Crater Lake National Park, P.O. Box 7, Crater Lake, Oregon 97604 USA (e-mail: [email protected]). Author for correspondence 2 USGS Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, 3200 SW Jefferson Way, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 USA Murray, Michael P., Christopher A. Pearl, and R. Bruce Bury. 2005. Apparent predation by Gray Jays, Perisoreus canadensis, on Long-toed Salamanders, Ambystoma macrodactylum, in the Oregon Cascade Range. Canadian Field-Naturalist 119(2): 291-292. We report observations of Gray Jays (Perisoreus canadensis) appearing to consume larval Long-toed Salamanders (Ambystoma macrodactylum) in a drying subalpine pond in Oregon, USA. Corvids are known to prey upon a variety of anuran amphibians, but to our knowledge, this is the first report of predation by any corvid on aquatic salamanders. Long-toed Salamanders appear palatable to Gray Jays, and may provide a food resource to Gray Jays when salamander larvae are concentrated in drying temporary ponds. Key Words: Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis, Long-toed Salamander, Ambystoma macrodactylum, amphibian, corvid, diet, larvae, pond. Corvid birds are generalist feeders and “oppor- vations, the pond had dried to a small pool (approxi- tunistic” predators (Bent 1946; Marshall et al. 2003). In mately 40 m2) which was about 5% of the area cov- montane regions of western North America, corvids ered when full. We observed two Gray Jays foraging sometimes consume anuran amphibians, which can at a muddy circular depression (0.3 m diameter) offer a concentrated food resource in breeding or larval located 2 m from the only remaining pool in the pond rearing aggregations (Beiswenger 1981; Olson 1989; basin. -

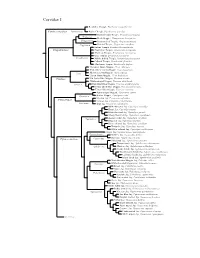

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Nesting Behavior of the Clark Nutcracker

THE CONDOR VOLUME 58 : JANUARY-FEBRUARY, 1956 NUMBER 1 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF THE CLARK NUTCRACKER By L. RICHARD MEWALDT In March and April of 1947, near Missoula, Montana, detailed observations were made of the nesting activities of a pair of Clark Nutcrackers, Nucifruga columbiana. A few additional data were obtained from three other nests in 1947 and one nest in 1948, all near Missoula, and from one nest in 1952 in Stevens County, Washington. Since plans to supplement the 1947 findings with further detailed observations have not materialized, it seems wise to present the material on hand at this time. Bendire (1889) first found nesting Clark Nutcrackers in 1876 in the Blue Moun- tains of Oregon. His account and those of Bradbury (1917) and of Dixon (1934) in- clude observations on nesting behavior. Briefer accounts of nesting include those of Pyfer (1897), Parker (1900), Johnson (1900 and 1902), Silloway (1903), Saunders (1910), Skinner (1916), Racey (1926), Bee and Hutchings (1942), Mewaldt (1948 and 1954), and LaFave (1954). Nesting activities of the Thick-billed Nutcracker, Nucifraga cqryocatactes caryo- catactes of northeastern and eastern Europe are but little better known than those of the Clark Nutcracker. Among the more important accounts on the European species are those of Vogel (1873), Bartels and Bartels (1929), and Steinfatt (1944). A signit% cant study of the Thick-billed Nutcracker is being made in Sweden by P. 0. Swanberg (1951 and personal communication). Except for two accounts (Formosof, 1933, and Grote, 1947), information on the Slender-billed Nutcracker, Nucifraga caryocatactes macrorhynchos of the USSR is generally less available.