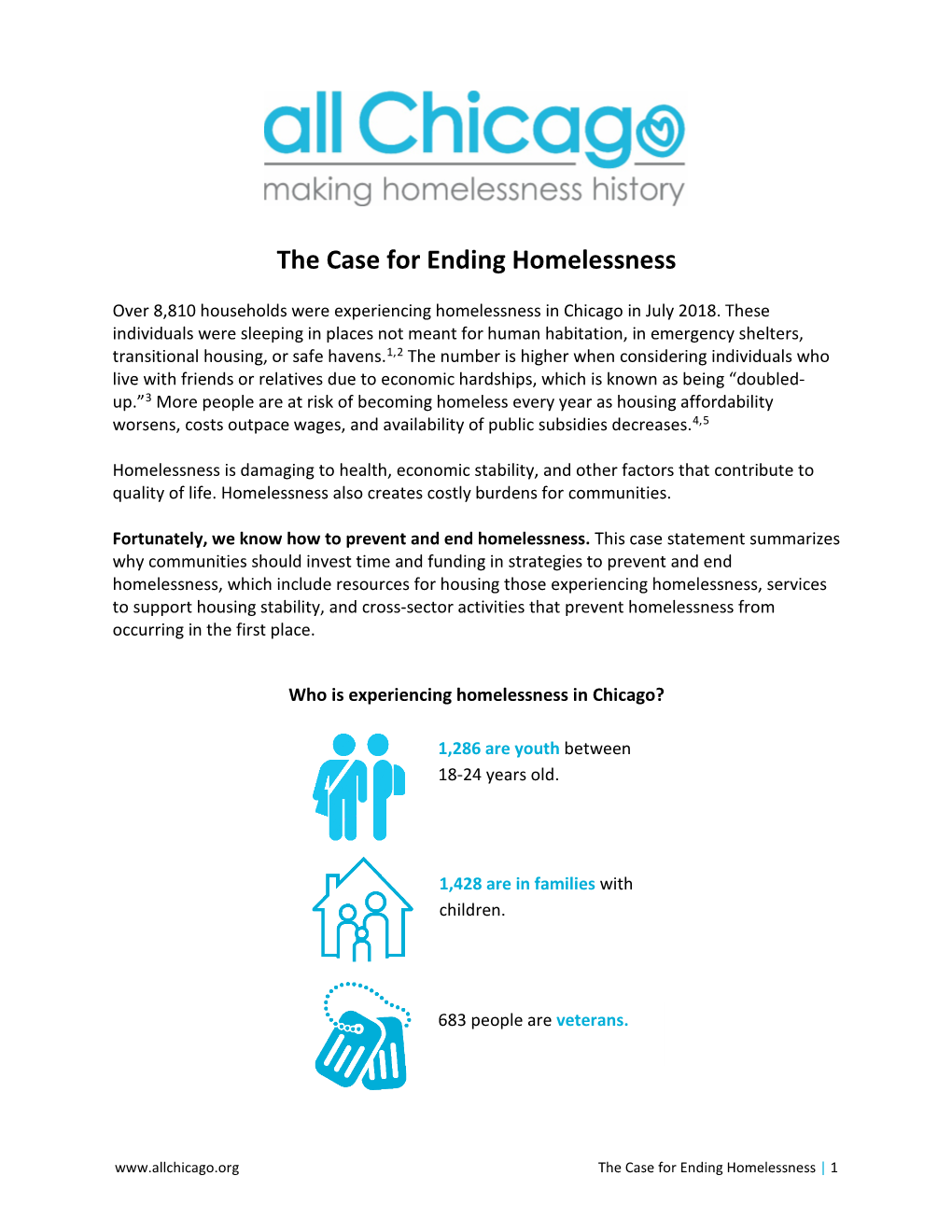

The Case for Ending Homelessness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Systems to End Family Homelessness

Family Connection Building Systems to End Family Homelessness Ending homelessness for families and children is a priority for the nation and for every The Plan community. By providing the right amount of assistance to help families obtain or regain Opening Doors: permanent housing as quickly as possible and ensuring access to services to remain stably Federal Strategic housed, achieving an end to family homelessness is possible. Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness Defining an End to Family Homelessness sets the goal to end family homelessness Given the current economic realities in most communities, situations in which families experience a crisis in 2020. and lose their home will likely occur. Recognizing this reality, USICH and federal partners adopted a vision of an end to family homelessness to mean that no family will be without shelter and homelessness will be a rare and brief occurrence. To achieve an end to family homelessness, we encourage communities to join us to strengthen our local crisis response systems together. What We Know Families experiencing Working together with our partners at the state, local, and federal level to strengthen the local homelessness are crisis response systems, we will: very similar to other • Ensure that no family is living unsheltered, low-income families. • Shorten episodes of family homelessness by providing resources that enable families to safely They face many reenter permanent housing as quickly as possible, obstacles such as • Link families to the benefits, supports, and community-based services they need to achieve and low education level, maintain housing stability, and domestic violence, • Identify and implement effective prevention methods to help families avoid homelessness. -

The Role of the Philanthropic Sector in Addressing Homelessness: Australian and International Experiences

The Role of the Philanthropic Sector in Addressing Homelessness: Australian and International Experiences Literature Review National Homelessness Research Partnership Program Dr Selina Tually, Miss Victoria Skinner and Associate Professor Michele Slatter Centre for Housing, Urban and Regional Planning The University of Adelaide Contact: Dr Selina Tually Centre for Housing, Urban and Regional Planning The University of Adelaide Phone: (08) 8313 3289 Email: [email protected] September 2012 Project No. FP8 This project is supported by the Australian Government through the Flinders Partners National Homelessness Research Partnership funded as part of the National Homelessness Research Agenda of the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. 2 of 103 Acronyms ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics ACNC Australian Charity and Not-For-Profit Commission ACOSS Australian Council of Social Service ACTCOSS Australian Capital Territory Council of Social Service AIHW Australian Institute of Health and Welfare ASIC Australian Securities and Investment Commission ATO Australian Taxation Office DGR Deductible Gift Recipient FaHCSIA Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs FBT Fringe Benefit Tax GFC Global Financial Crisis GST Goods and Services Tax ITEF Income Tax Exempt Fund J2SI Journey to Social Inclusion NAHA National Affordable Housing Agreement NCOSS Council of Social Service of New South Wales NFG Neighborhood Funders Group (US) NFP Not For Profit NP Non-Profit NTCOSS -

A Survey of Homelessness Laws

The Forum September 2020 Is a House Always a Home?: A Survey of Homelessness Laws Marlei English J.D. Candidate, SMU Dedman School of Law, 2021; Staff Editor for the International Law Review Association Find this and additional student articles at: https://smulawjournals.org/ilra/forum/ Recommended Citation Marlei English, Is a House Always a Home?: A Survey of Homelessness Laws (2020) https://smulawjournals.org/ilra/forum/. This article is brought to you for free and open access by The Forum which is published by student editors on The International Law Review Association in conjunction with the SMU Dedman School of Law. For more information, please visit: https://smulawjournals.org/ilra/. Is a House Always a Home?: A Survey of Homelessness Laws By: Marlei English1 March 6, 2020 Homelessness is a plague that spares no country, yet not a single country has cured it. The type of legislation regarding homelessness in a country seems to correlate with the severity of its homelessness problem. The highly-variative approaches taken by each country when passing their legislation can be roughly divided into two categories: aid-based laws and criminalization laws. Analyzing how these homelessness laws affect the homeless community in each country can be an important step in understanding what can truly lead to finding the “cure” for homelessness rather than just applying temporary fixes. I. Introduction to the Homelessness Problem Homelessness is not a new issue, but it is a current, and pressing issue.2 In fact, it is estimated that at least 150 million individuals are homeless.3 That is about two percent of the population on Earth.4 Furthermore, an even larger 1.6 billion individuals may be living without adequate housing.5 While these statistics are startling, the actual number of individuals living without a home could be even larger because these are just the reported and observable numbers. -

THE CULTURE of HOMELESSNESS: an Ethnographic Study

THE CULTURE OF HOMELESSNESS: An ethnographic study Megan Honor Ravenhill London School of Economics PhD in Social Policy UMI Number: U615614 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615614 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I V|£:S H S f <§195 I O I S S 4 -7 ABSTRACT The thesis argues that homelessness is complex and synergical in nature. It discusses the life events and processes that often trigger, protect against and predict the likelihood of someone becoming homeless (and/or roofless). It argues, that people’s routes into homelessness are complex, multiple and interlinked and are the result of biographical, structural and behavioural factors. This complexity increases with the age of the individual and the duration of their rooflessness. The thesis explores the homeless culture as a counter-culture created through people being pushed out of mainstream society. It argues, that what happened to people in the past, created the nature of the homeless culture. Furthermore it is argued that any serious attempt at resettling long-term rough sleepers needs to consider what it is that the homeless culture offers and whether or how this can be replicated within housed society. -

Designing out Homelessness: Practical Steps for Business 2020

DESIGNING OUT HOMELESSNESS: PRACTICAL STEPS FOR BUSINESS 2020 Practical steps designed for employers to take action to prevent homelessness. In partnership with: CONTENTS FOREWORDS 3 INTRODUCTION 5 REFRAMING HOMELESSNESS 6 PREVENTION 8 PRACTICAL HELP AND SUPPORT 10 PATHWAYS TO EMPLOYMENT 16 CHECKLIST 18 DIRECTORY 20 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 23 REFERENCES 23 2 Business in the Community 2020 FOREWORDS FOREWORD BY LYNNE SHEEHY, LEGAL & GENERAL For thousands of people in Wales, including support to help them when they most need it. people from working households, homelessness Some examples of how we do this are illustrated is a frightening reality. in the toolkit. Recently, a group of leading responsible I felt with both hats on, committing to creating a businesses in Wales, who form the BITC Cymru homelessness toolkit for employers and Community Impact Leadership Team (CILT) have employees made perfect sense. It’s a great focussed on homelessness. The CILT aims to opportunity to turn the understanding we’ve lead and inspire businesses by acting as gained into something tangible and demonstrates ambassadors for community impact and taking the value of working together as responsible collaborative action on key social issues to help businesses in Wales to achieve community create vibrant and resilient places. impact at scale on such an important issue. Through collaborating with others in the BITC Everybody has the right to feel safe and secure Cymru network, the group has learnt more about and by working together we can help make a the issue and gained a good understanding of difference. how responsible businesses can support their employees before they end up in crisis. -

Parity Vol25-01 (April) Parity Vol25-01 9/05/12 2:04 PM Page 1

Parity Vol25-01 (April)_Parity Vol25-01 9/05/12 2:04 PM Page 1 PARITY Philanthropic, Corporate andPrivate Sector APRIL 2012 Print Post approved PP328866/0060 ISSN 1032-6170 ABN 20 005 475 007 Responses to Homelessness VOLUME 25 • ISSUE 1 Parity Vol25-01 (April)_Parity Vol25-01 9/05/12 2:04 PM Page 2 PARITY · Volume 25, Issue 1 · April 2012 Issue 1 · 25, Volume · PARITY Council to Homeless Persons Jenny Smith: Chief Executive Officer Sarah Kahn: Manager Policy and Communications Unit Ian Gough: Manager Consumer Contents Programs Lynette Deakes: Acting Office Manager Noel Murray: Publications Foreword 3 Coordinator The Hon. Brendan O’Connor MP, Minister for Housing, Minister for Homelessness, Minister for Small Business Lisa Kuspira: Acting Communications Editorial 4 and Policy Officer Angela Welcome to CHP: 4 Kyriakopoulos: HAS Advocate Introducing Ian Gough, Manager Consumer Programs CHP Cassandra Bawden: Peer Education and NEWS Support Program Team Australian Homelessness Clearinghouse 5 Leader Akke Halme: Bookkeeper HomeGround Launches Disability Action Plan 5 Address: 2 Stanley St, New Research Project: 6 Collingwood, Beyond Charity: The Engagement of the Philanthropic and Melbourne 3066 Homelessness Sectors in Australia Phone: (03) 8415 6200 Fax: (03) 9416 0200 Researchers: Selina Tually and Michele Slatter, The University of Adelaide, Jo Baulderstone and Loretta Geuenich, Flinders University, Shelley Mallett, Hanover Welfare Services and Ross Womersley, SACOSS. E-mail: [email protected] Funder: FaHCSIA as part of the National Homelessness Research Agenda. Promotion of Conferences, How Many People in Boarding Houses? 7 Events and Publications By Chris Chamberlain, Director, Centre for Applied Social Research, RMIT University Organisations are invited to have their FEATURE promotional fliers included in the monthly Philanthropic, Corporate and Private Sector mailout of Parity. -

The Roadmap for the Prevention of Youth Homelessness

The Roadmap for the Prevention of Youth Homelessness Stephen Gaetz, Kaitlin Schwan, Melanie Redman, David French, & Erin Dej Edited by: Amanda Buchnea The Roadmap for the Prevention of Youth Homelessness How to Cite Gaetz, S., Schwan, K., Redman, M., French, D., & Dej, E. (2018). The Roadmap for the Prevention of Youth Homelessness. A. Buchnea (Ed.). Toronto, ON: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press. ISBN: 978-1-77355-026-8 Acknowledgements The Roadmap builds upon the insights and wisdom of young people with lived experience of homelessness who participated in What Would it Take? Youth Across Canada Speak Out on Youth Homelessness Prevention. The authors would like to thank these young people for lending their voices to this work. We hope their insights will guide policy and practice reform across the country. This report also draws from the conceptual framing and scholarship of A New Direction: A Framework for Homelessness Prevention and Coming of Age: Reimagining the Response to Youth Homelessness. This report also builds upon the evidence reviewed in Youth Homelessness Prevention: An International Review of Evidence. The recommendations in this report build upon those within several policy briefs and reports published by the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness and A Way Home Canada. We wish to thank the authors of these documents for their insights, and hope this report will amplify the impact of their work. The authors wish to thank the many scholars, advocates, and community members who provided feedback on earlier drafts of the Roadmap, including: Dr. Naomi Nichols, Jayne Malenfant, Jonathan Robart, Duncan Farthing-Nichol, Dr. Peter Mackie, Dr. -

IFLA Guidelines for Library Services to People Experiencing Homelessness

IFLA Guidelines for Library Services to People Experiencing Homelessness Developed by the IFLA Library Services to People with Special Needs (LSN) Section August 2017 Endorsed by the IFLA Professional Committee Library Services to People with Special Needs Guidelines Working Group, 2017 2 © 2017 by LSN Guidelines Working Group and Julie Ann Winkelstein, Consultant and Primary Editor. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 IFLA P.O. Box 95312 2509 CH Den Haag Netherlands www.ifla.org 3 Table of Contents Preface ........................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 12 1.1 Development of Guidelines in an international context ........................................................... 12 1.2 Why are the Guidelines necessary? .............................................................................................. 13 1.2.1 Overcoming prejudices ........................................................................................................... 13 1.2.2 Identifying barriers and how to overcome them................................................................. 13 1.2.3 Worldwide library services to people experiencing homelessness ................................... -

Searching out Solutions: Constructive Alternatives to Criminalization

SEARCHING OUT SOLUTIONS Constructive Alternatives to the Criminalization of Homelessness United States Interagency Council on Homelessness 2012 Table of Contents Examples 26 Executive Summary 3 Benefits 28 Challenges 28 Introduction 7 Resources 29 Homelessness in America 7 Criminalization Undermines Solution III: Alternative Justice System Real Solutions 8 Strategies 30 The Search for Constructive Background 30 Alternatives 10 Potential Strategies 31 Examples 32 Solution I: Comprehensive and Seamless Benefits 36 Systems of Care 12 Challenges 37 Background 12 Resources 38 Potential Strategies 12 Examples 15 Conclusion 41 Benefits 21 Challenges 22 Sponsoring Agencies and Resources 23 Partners & Resources 42 Solution II: Collaboration among Law Appendix I: Meeting Agenda 44 Enforcement, Behavioral Health and Social Service Providers 25 Appendix II: Discussion Points 45 Background 25 Potential Strategies 25 Appendix III: Summit Participants 53 Searching out Solutions: Constructive Alternatives to Criminalization Executive Summary In recent years, the United States has seen the proliferation of local measures to criminalize “acts of living” laws that prohibit sleeping, eating, sitting, or panhandling in public spaces. City, town, and county officials are turning to criminalization measures in an effort to broadcast a zero-tolerance approach to street homelessness and to temporarily reduce the visibility of homelessness in their communities. Although individuals experiencing homelessness should be afforded the same dignity, compassion, and support -

Strengthening Partnerships Between Law Enforcement and Homelessness Services Systems

Strengthening Partnerships Between Law Enforcement and Homelessness Services Systems June 2019 Strengthening Partnerships Between Law Enforcement and Homelessness Services Systems June 2019 At the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, we coordinate and catalyze the federal response to homelessness, working in close partnership with senior leaders across our 19 federal member agencies. By organizing and supporting homelessness services system leaders, as well as Governors, Mayors, and other local officials, we drive action to achieve the goals of the federal strategic plan to prevent and end homelessness—and ensure that homelessness in America is ended once and for all. The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center is a national nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that combines the power of a membership association, representing state officials in all three branches of government, with policy and research expertise to develop strategies that increase public safety and strengthen communities. For more information about the CSG Justice Center, visit www.csgjusticecenter.org. U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness 1 The Council of State Governments Justice Center Strengthening Partnerships Between Law Enforcement and Homelessness Services Systems June 2019 Introduction Across the country, local law enforcement and homelessness service system leaders are grappling with the significant, often rising numbers of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness, and they are seeking solutions. As first responders, law enforcement officers -

5Th June 2020 to the House of Representatives Standing

02 4325 3540 [email protected] PO Box 1234 Gosford NSW 2250 5th June 2020 To the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs, Inquiry into Homelessness in Australia Coast Shelter is a homelessness service based in Gosford Local Government Area and Wyong Local Government Area working with Youth, Women & Children and Men who are homeless or at risk of homelessness along with Women escaping Domestic and Family Violence. We welcome the opportunity to provide a response to the Inquiry into Homelessness in Australia. We seek to respond to the term of reference regarding services to support people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness, including housing assistance, social housing, and specialist homelessness services. As service providers, we directly engage with the growing homelessness crisis through assisting those at risk of and experiencing homelessness. NSW experienced the highest rate of homelessness across states and territories from 2011- 2016, with the number increasing by 37% in this period, significantly higher than the national increase of 14%.1 During a similar period, homelessness services have experienced unprecedented demand, with a 38% increase in clients from 2014 – 2016.2 This level of demand has been maintained since 2016. In 2018-19 homeless services across NSW saw over 73, 000 clients, 27% more than they are funded to support.3 We are funded to work with 876 clients but in 2018-19 we supported over 1151 clients experiencing homelessness and a further 914 women & children escaping domestic and family violence. The COVID-19 pandemic has further increased these pressures. -

HOMELESSNESS in OREGON a Review of Trends, Causes, and Policy Options

HOMELESSNESS IN OREGON A Review of Trends, Causes, and Policy Options March 2019 Prepared for: The Oregon Community Foundation FINAL REPORT Acknowledgments This report was written by John Tapogna and Madeline Baron with research assistance from Ryan Knapp, Jeff Lane, and Virginia Wiltshire-Gordon, and editorial support from Laura Knudson. The authors would also like to recognize Ingrid Gould Ellen and Brendan O’Flaherty—editors of How to House the Homeless (Russell Sage Foundation, 2010). The policy framework advanced in this report draws heavily on their book's insights. The authors are solely responsible for any errors or omissions. Executive Summary Executive Summary Purpose of the Report Oregon’s homeless crisis stretches across the state. Jackson County’s homeless population recently hit a seven-year high. During 2017-2018, the number of adults living on the streets, under bridges, or in cars increased by 25.8 percent in Central Oregon. Conditions faced by Lane County’s growing unsheltered homeless population triggered the threat of a lawsuit. And news reports have profiled challenges from Astoria to Ontario. The homeless crisis dominated the 2018 state and local elections. Rival candidates debated camping regulations, sit-lie ordinances, street cleanups, and the use of jails as shelters. Post- election, Governor Kate Brown has advanced a range of initiatives aimed at preventing and addressing homelessness—with a special emphasis on children, veterans, and the chronically homeless. Meanwhile, cities and counties across the state—building on federal and state programs—are crafting localized responses to address the crisis. This report seeks to advance the policy discussion for a problem that some Oregonians consider intractable.