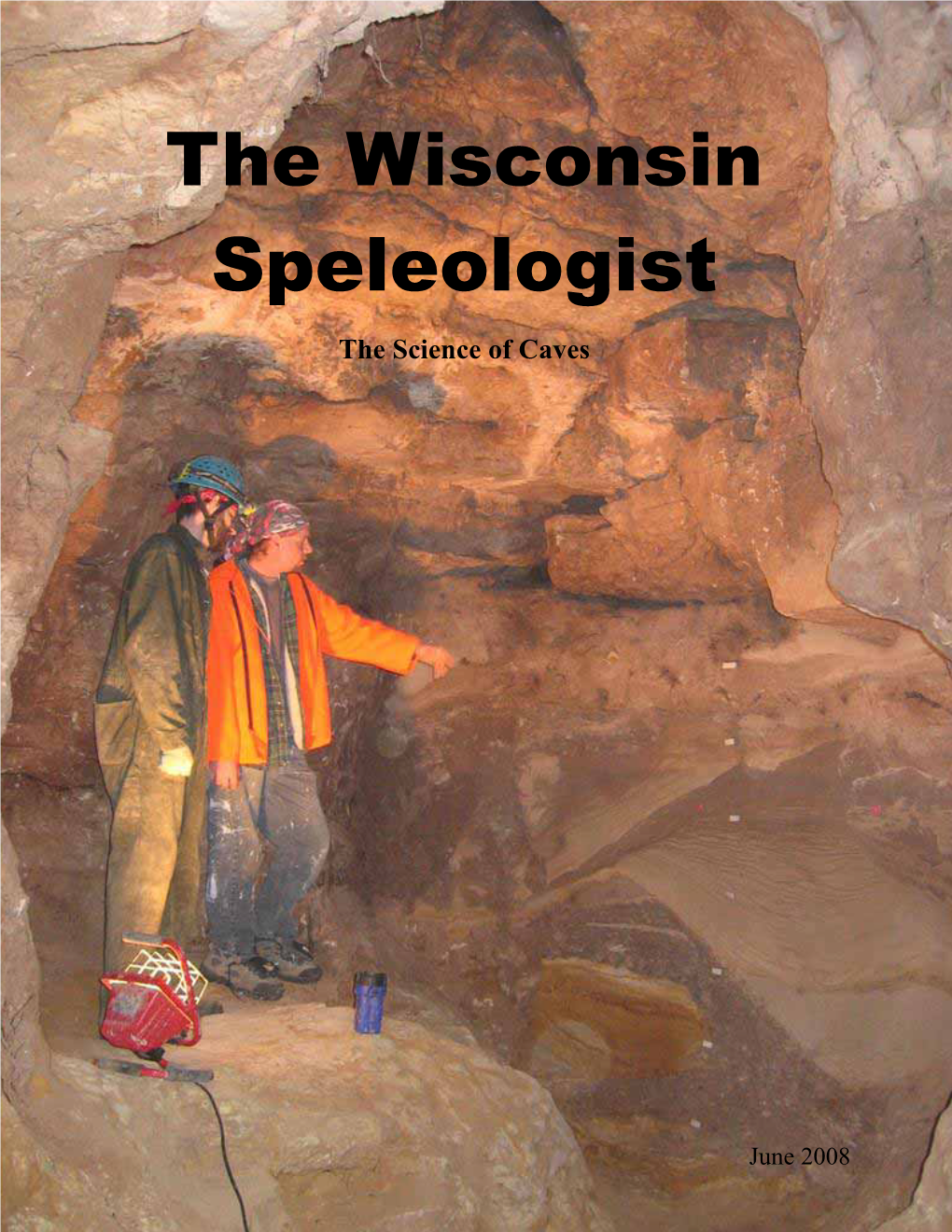

The Wisconsin Speleologist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Wants to Be a Speleologist?

Timpanogos Cave Edition Diantha Smith, 2009 Rules of the Game! 1. Read each question and all choices carefully. 2. Choose an answer or choose a life line. 3. If you get the answer correct you continue answering. 4. If you answer incorrectly, another player gets the next question. 5. LEARN A LOT AND HAVE FUN! Ask the audience: The audience will raise their hands to show which question they think the player should choose. Fifty/Fifty: The game host will reveal two answers that are not correct, leaving two choices for the player . Info Sheet: The player may consult the Cave Information Sheet for one minute to try and find the answer. (Beware: not all answers are on the sheet!) $1,000,000 $500,000 Is that your final $250,000 answer? $100,000 $50,000 How do we know that the limestone in Mount $25,000 Timpanogos was formed in ancient sea beds? $10,000 $5,000 $1,000 A: lots of salt B: smells like the ocean $500 $200 C: fossils of sea creatures D: pirate ghosts $100 $1,000,000 $500,000 $250,000 $100,000 $50,000 How do we know that many caves, like Timpanogos, $25,000 are formed in rock from ancient sea beds? $10,000 $5,000 $1,000 A: large salt content B: smell like the ocean $500 $200 C: fossils of sea creatures D: pirate ghosts $100 $1,000,000 $500,000 Is that your final $250,000 answer? $100,000 $50,000 What is the length and weight of the $25,000 Great Heart stalactite? $10,000 $5,000 $1,000 A: 5 ½ ft. -

Cave Research Foundation

CAVE RESEARCH FOUNDATION QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER FEBRUARY 2 005 VOLUME 33, NO. 1 SPOTLIGHT ON MAMMOTH CAVE See Mammoth Cave Expedition Reports, pages 6-11 2 CRF NEWSLETTER Annual Report Submission Guidelines for 2004 Volume 33, No.I The Cave Research Foundation solicits reports established 1973 from CRF operations areas, research expeditions, pro Send all articles and reports for submission to: jects, and sponsored scientific and historical research William Payne, Editor projects for the 2004 Annual Report. The deadline for 5213 Brazos Midland, TX 79707-3161 submissions is March 1, 2005. Maps, photos, line drawings, charts, tables and The CRF Newsletter is a quarterly publication of the other images are an important part of the report and Cave Research Foundation, a non-profit organization should be chosen and prepared with the goal of com incorporated in 1957 under the laws of Kentucky for the municating significant achievements and discoveries purpose of furthering research, conservation, and during 2004. education about caves and karst. A new feature for the 2004 Annual Report will be Newsletter Submissions & Deadlines: the limited inclusion of color photos. High quality, Original articles and photographs are welcome. If intending to jointly submit material to another publication, please in high-resolution photos will be needed for the front and form the CRF editor. Publication cannot be guaranteed, espe back covers. If enough high-quality submissions are cially if submitted elsewhere. All material is subject to revi received and the printing budget warrants it, there may sion unless the author specifically requests otherwise. For be a color plate insert in the report. -

TITLE PAGE.Wpd

Proceedings of BAT GATE DESIGN: A TECHNICAL INTERACTIVE FORUM Held at Red Lion Hotel Austin, Texas March 4-6, 2002 BAT CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL Edited by: Kimery C. Vories Dianne Throgmorton Proceedings of Bat Gate Design: A Technical Interactive Forum Proceedings of Bat Gate Design: A Technical Interactive Forum held March 4 -6, 2002 at the Red Lion Hotel, Austin, Texas Edited by: Kimery C. Vories Dianne Throgmorton Published by U.S. Department of Interior, Office of Surface Mining, Alton, Illinois and Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois U.S. Department of Interior, Office of Surface Mining, Alton, Illinois Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois Copyright 2002 by the Office of Surface Mining. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bat Gate Design: A Technical Interactive Forum (2002: Austin, Texas) Proceedings of Bat Gate Design: Red Lion Hotel, Austin, Texas, March 4-6, 2002/ edited by Kimery C. Vories, Dianne Throgmorton; sponsored by U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Office of Surface Mining and Fish and Wildlife Service, Bat Conservation International, the National Cave and Karst Management Symposium, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, the National Speleological Society, Texas Parks and Wildlife, the Lower Colorado River Authority, the Indiana Karst Conservancy, and Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-885189-05-2 1. Bat ConservationBUnited States Congresses. 2. Bat Gate Design BUnited States Congresses. 3. Cave Management BUnited State Congresses. 4. Strip miningBEnvironmental aspectsBUnited States Congresses. -

Karst Geology

National Park Service Mammoth Cave U.S. Department of the Interior Mammoth Cave National Park Karst Geology Look Beneath Beneath the surface of South Central Kentucky lies a world characterized by miles of dark, seemingly endless passageways. The geological processes which formed this world referred to as Mammoth Cave began hundreds of millions of years ago and continue today. The Ancient World 350 million years ago the North American continent About 280 million years ago the sea level started to was located much closer to the equator. A shallow fall exposing the layers of limestone and sandstone. sea covered most of the southeastern United States, Additional tectonic forces caused the earth’s crust and its warm water supported a dense population of to slowly rise causing cracks to form in and between tiny organisms whose shells were made of calcium the limestone and sandstone formations. As the up- carbonate (CaCO3). As these creatures died, their lift continued, rivers developed which over millions shells accumulated by the billions on the sea fl oor. of years have created the sandstone-capped plateau In addition, calcium carbonate can precipitate from above the Green River and the low, almost fl at lime- the water itself. The build-up of material continued stone plain which extends southeast of I-65. for 70 million years accumulating seven hundred feet of limestone and shale followed by sixty feet of sandstone that was deposited over much of the area by a large river system fl owing into the sea from the north. “Acid Rain” Rain water, acidifi ed by carbon dioxide in the soil water, they enlarged faster. -

Bat Caves in Fiji

Bat caves in Fiji Status and conservation of roosting caves of the Fiji blossom bat (Notopteris macdonaldi), the Pacific sheath-tailed bat (Emballonura semicaudata) and the Fiji free-tailed bat (Chaerephon bregullae). Joanne Malotaux NatureFiji-MareqetiViti July 2012 Bat caves in Fiji Status and conservation of roosting caves of the Fiji blossom bat (Notopteris macdonaldi), the Pacific sheath-tailed bat (Emballonura semicaudata) and the Fiji free-tailed bat (Chaerephon bregullae). Report number: 2012-15 Date: 27th June 2012 Prepared by: Joanne Malotaux, intern at NatureFiji-MareqetiViti NatureFiji-MareqetiViti 14 Hamilton-Beattie Street Suva, Fiji Cover page picture: Wailotua cave. © Joanne Malotaux. 1 CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Chapter 1. Cave-dwelling bat species...................................................................................................... 4 Fiji blossom bat .................................................................................................................................... 4 Pacific sheath-tailed bat ...................................................................................................................... 5 Fiji free-tailed bat ................................................................................................................................ 6 Chapter 2. General recommendations ................................................................................................... -

Dicionarioct.Pdf

McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Earth Science Second Edition McGraw-Hill New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2003 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be repro- duced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-141798-2 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-141045-7 All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw- Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decom- pile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

Caves in Slovakia

Caves in Slovakia ► Caves are real natural gems. Some Slovakia caves are interesting by their rich and unique decoration, others by archaeological excavations. You will be awed by geomorphologic cave structures: stalactites, stalagmites, tufa cascades and curtains, pillars, mounds, pea like and lake formations or soft tufa and eccentric formations. ► Slovakia is extremely rich in caves. 5,450 is the total number of our known caves in Slovakia, but new caves are being discovered constantly. Most of them are situated in Slovak Karst, Low Tatras and Spis – Gemer Karst (Slovak Paradise and Muran Plain), Great Fatra, Western, Eastern and Belianske Tatras. There is no other such concentration of caves with so high representative value located in the karst region of the mild climate zone as in Slovakia. 12 Slovak caves opened to public ► * Belianska Cave * Driny * Gombasecká Cave ► * Bystrianska Cave * Harmanecká Cave ► * Demänovská Cave of Liberty * Jasovská Cave ► * Demänovská Ice Cave * Ochtinská Aragonite Cave ► * Dobšinská Ice Cave * Važecká Cave ► * Domica Belianska cave is located in an attractive environment of the Tatra National Park ► The cave length is 3,640 m with elevation range of 160 m. The entrance parts, accessible through thirled tunnel, contain chimney spaces opening into them and leading from the upper original entrance situated 82 m above the present one. Belianska cave was open for public through the original entrance as early as in 1882. Electrically lit is the cave from 1896. Bystrianska cave is located on the southern edge of the Bystrá village, between Podbrezová and Mýto pod Ďumbierom. ► The cave was formed by tectonical and erosional processes and modelled by underground stream, which flows at present through the spaces 15 to 20 m under the show path. -

Canyons & Caves

CANYONS & CAVES A Newsletter from the Resource Management Offices Carlsbad Caverns National Park Issue No. 10 Fall 1998 HISTORIC ITEMS – Items of a historical nature continue to be moved around in Lower Cave and Slaughter Canyon Cave. Preserving America’s Natural and When items are moved, they are taken out of Cultural Heritage for future generations! context and information concerning their placement is lost. Moving an item also impacts the item and the cave floor. Please DO NOT move any historic item found in any cave. WELCOME to Steven Bekedam, a new SCA for Surface Edited by Dale L. Pate Resources. Steven EOD’s Oct. 1. TABLE OF CONTENTS WHAT’S HAPPENING IN SURFACE RESOURCES • Mountain Lion Transects begin again in October. The Resource News 1 dates for the transects are in the Calendar of Events. The Mystery of the Scattered Pearls 2 Contact David Roemer, ext. 373, if you’d like to Identifying Wetlands at Rattlesnake Springs 3 participate. Barite “Stalactites” in Lechuguilla 3 • The week of October 5 begins the field work to delineate Banner-tailed Kangaroo Rat 4 the active and historic wetlands boundaries at Rattlesnake Black-tailed Rattlesnake 4 Springs (see write up) Helictites and Subaqueous Helictites 5 • Renée Beymer and Diane Dobos-Bubno will attend two And the Times, They are a Change’n 5 back-to-back conferences in Albuquerque this November: Yes, We Have Algae 6 one focuses on vegetation management and one on Calendar of Events 8 riparian habitat and water use issues. RESOURCE NEWS CAVE RESOURCES VOLUNTEERS – Adios and thanks to Gosia Roemer and Jed Holmes for all the hard work they did SPRING AND SUMMER WEATHER – Hot and dry this summer. -

Some Unintended Results of Blanket Cave Closures: a Story About Fern Cave Jennifer Pinkley

Some Unintended Results of Blanket Cave Closures: a Story about Fern Cave Jennifer Pinkley The first time I visited Alabama’s Fern Along the way, explorers found beauti- Grotto members about gray bats and the Cave, I thought of the Mines of Moria in ful and rare helictites, gypsum crystals that need to avoid disturbing them. The Grotto JRR Tolkien’s Middle Earth: vast beyond look like giant corn flakes, huge dogtooth started to get the word out that cavers should imagining. As I moved through the cave, it spar calcite formations, rimstone dams, stay out of the approximately three miles of seemed that around every corner I discovered towering flowstone, giant rooms, deep pits, Morgue passage of the cave in the winter. another passage, another canyon, another cave pearls, and stream passage. In obscure Cavers complied. The bats thrived. path to explore. On that first bewildering rooms, cavers found bones of extinct animals trip, I visited Helictite Heaven, one of the that roamed the earth over 13,000 years MAnAgeMent under tHe us FisH And most beautiful and bizarre rooms not only in ago, including giant-sized varieties of cave WiLdLiFe serviCe Fern, but in any cave I’ve ever visited. Weird bears, armadillos, and lions. Hidden in the In 1980, the US Fish and Wildlife rock forms sprout out of the floors, walls and mud were also jaguar teeth, a horse tooth, Service (FWS) purchased all of the entrances ceilings like mutant, sparkling coral bushes. and a 2,400-year-old human jawbone. to Fern, except Surprise Pit, to protect the After that trip, I was hooked. -

Anthodite - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Anthodite - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Discussion Read Edit View history Anthodite From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Anthodites (Greek, anthos, “flower”, -ode, adjectival Contents combining form, -ite adjectival suffix) are speleothems (cave Featured content formations) composed of long needle-like crystals situated in Current events clusters which radiate outward from a common base. The Random article "needles" may be quill-like or feathery. Most anthodites are Donate to Wikipedia made of the mineral aragonite (a variety of calcium carbonate, Interaction CaCO3), although some are composed of gypsum Help (CaSO4·2H2O). About Wikipedia The term “anthodite” is first cited in the scientific literature in Community portal 1965 by Japanese researcher N. Kashima[1], who described Recent changes “flower-like dripstone” composed of “an alternation of calcite Contact Wikipedia and aragonite”[2][3]. Toolbox Contents [hide] Print/export 1 Structure, composition and appearance Anthodites are featured at the 2 Occurrence commercial Skyline Caverns in Virginia, 3 Types USA 4 Anthodite-like formations 5 References Structure, composition and appearance [edit] The individual crystals of anthodites develop in a form described as “acicular” (needle-like) and often branch out as they grow. They usually grow downward from a cave's ceiling. Aragonite crystals are contrasted with those made of calcite (another variety of calcium carbonate) in that the latter tend to be stubby or dog-tooth-like (“rhombohedral”, rather than acicular). Anthodites often have a solid core of aragonite and may have huntite or hydromagnesite deposited near the ends of the branches. Anthodite crystals vary in size from less than a millimeter to about a meter, but are commonly between 1 and 20 millimeters in length. -

Site Management Plan, Medford District BLM

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Background ............................................................................................................................... 3 II. Life History .............................................................................................................................. 4 Habitat Associations ................................................................................................................... 4 Roosting Ecology ........................................................................................................................ 4 Foraging Behavior, Habitat, and Diet ......................................................................................... 6 Reproduction and Development ................................................................................................. 6 Behavioral ecology ..................................................................................................................... 7 III. Threats..................................................................................................................................... 7 IV. General Management Direction for Townsend’s Big-eared Bat Roost Sites ........................ 8 V. Grants Pass Resource Area Sites .......................................................................................... 10 Oak Mine .................................................................................................................................. 10 Gopher / Baby / Lamb Mine .................................................................................................... -

Cave Research Foundation Annual Report - 2001-2003

Cave Research Foundation Annual Report - 2001-2003 1 Cave Research Foundation Annual Report - 2001-2003 2 Cave Research Foundation Annual Report - 2001-2003 Annual Reports 2001-2003 Cave Research Foundation 177 Hamilton Valley Road Cave City, Kentucky 42127 Cave Research Foundation Cave Research 3 Cave Research Foundation Annual Report - 2001-2003 The Cave Research Foundation (CRF) is a private non-profit organization incorporated in 1957 under the laws of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Its purpose is to: Facilitate research, management, and interpretation of caves and karst resources Form partnerships to study, protect and preserve cave resources and karst areas Promote the long-term conservation of caves and karst resources Editors: Patricia Kambesis Elizabeth Winkler Hoffman Environmental Research Institute 238 Tyler Court Western Kentucky University Smiths Groves, Kentucky 42171 1906 College Heights Blvd. Bowling Green, Kentucky 42101 Hawkins River at the Amos Hawkins Formation, Mammoth Cave Cover layout and photo: Gary Berdeaux Cave Research Foundation 2001-2003 Annual Report c by the Cave Research Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to reproduce this material for scientific and educational use only. For information contact CRF, 177 Hamilton Valley Road, Cave City, KY 42127-45424 ISBN 978-0-939748-59-4 Published by Cave Books 4700 Amberwood Drive Dayton, Ohio 45424 4 Cave Research Foundation Annual Report - 2001-2003 Table of Contents Cave Research Foundation Activities 2001 2001 Highlights ..............................................................................................................................................................