Cave Research Foundation Annual Report - 2001-2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cave Research Foundation

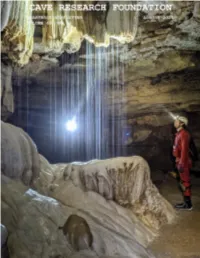

CAVE RESEARCH FOUNDATION QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER FEBRUARY 2 005 VOLUME 33, NO. 1 SPOTLIGHT ON MAMMOTH CAVE See Mammoth Cave Expedition Reports, pages 6-11 2 CRF NEWSLETTER Annual Report Submission Guidelines for 2004 Volume 33, No.I The Cave Research Foundation solicits reports established 1973 from CRF operations areas, research expeditions, pro Send all articles and reports for submission to: jects, and sponsored scientific and historical research William Payne, Editor projects for the 2004 Annual Report. The deadline for 5213 Brazos Midland, TX 79707-3161 submissions is March 1, 2005. Maps, photos, line drawings, charts, tables and The CRF Newsletter is a quarterly publication of the other images are an important part of the report and Cave Research Foundation, a non-profit organization should be chosen and prepared with the goal of com incorporated in 1957 under the laws of Kentucky for the municating significant achievements and discoveries purpose of furthering research, conservation, and during 2004. education about caves and karst. A new feature for the 2004 Annual Report will be Newsletter Submissions & Deadlines: the limited inclusion of color photos. High quality, Original articles and photographs are welcome. If intending to jointly submit material to another publication, please in high-resolution photos will be needed for the front and form the CRF editor. Publication cannot be guaranteed, espe back covers. If enough high-quality submissions are cially if submitted elsewhere. All material is subject to revi received and the printing budget warrants it, there may sion unless the author specifically requests otherwise. For be a color plate insert in the report. -

Cave Research Foundation (CRF) Is a 501(C)(3) Organization Founded in Kentucky in 1957 for the Purpose of Facilitating Cave Research

CAVE RESEARCH FOUNDATION Ozarks Operation Area by Scott House The Cave Research Foundation (CRF) is a 501(c)(3) organization founded in Kentucky in 1957 for the purpose of facilitating cave research. Today it continues its mission with operations across the country and in expeditions around the world. The CRF is administered by officers, a board and an operations council. An operations manager is appointed by the CRF board to coordinate and oversee activities within an operation. Other individuals within the operation may head specific projects or act as functionaries of one sort or another. Following is a brief description of various CRF Ozarks Operation projects. Mark Twain National Forest: CRF works with Mark Twain National Forest (USFS) through a series of cooperative agreements and modifications. These cooperative agreements superseded challenge cost-share agreements and volunteer agreements. Cave Mapping and Biological Inventory: This has been our largest and longest running project. It originated in 1990 with a management concern centered on an application by the Doe Run Company for mineral prospecting within the Eleven Point and Current River watersheds. The aim was to document all caves within the 250 square kilometer mineral lease area by detailed mapping, biological inventory and comprehensive descriptions. More than 120 caves were visited and documented over the 6 year course of the study. Following on from that initial phase, MTNF has continued to provide funding, through one vehicle or another, for an expanded project which is gradually documenting caves throughout the Mark Twain National Forest. Approximately 450 caves have been documented during this ongoing study. -

TITLE PAGE.Wpd

Proceedings of BAT GATE DESIGN: A TECHNICAL INTERACTIVE FORUM Held at Red Lion Hotel Austin, Texas March 4-6, 2002 BAT CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL Edited by: Kimery C. Vories Dianne Throgmorton Proceedings of Bat Gate Design: A Technical Interactive Forum Proceedings of Bat Gate Design: A Technical Interactive Forum held March 4 -6, 2002 at the Red Lion Hotel, Austin, Texas Edited by: Kimery C. Vories Dianne Throgmorton Published by U.S. Department of Interior, Office of Surface Mining, Alton, Illinois and Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois U.S. Department of Interior, Office of Surface Mining, Alton, Illinois Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois Copyright 2002 by the Office of Surface Mining. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bat Gate Design: A Technical Interactive Forum (2002: Austin, Texas) Proceedings of Bat Gate Design: Red Lion Hotel, Austin, Texas, March 4-6, 2002/ edited by Kimery C. Vories, Dianne Throgmorton; sponsored by U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Office of Surface Mining and Fish and Wildlife Service, Bat Conservation International, the National Cave and Karst Management Symposium, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, the National Speleological Society, Texas Parks and Wildlife, the Lower Colorado River Authority, the Indiana Karst Conservancy, and Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-885189-05-2 1. Bat ConservationBUnited States Congresses. 2. Bat Gate Design BUnited States Congresses. 3. Cave Management BUnited State Congresses. 4. Strip miningBEnvironmental aspectsBUnited States Congresses. -

Bat Caves in Fiji

Bat caves in Fiji Status and conservation of roosting caves of the Fiji blossom bat (Notopteris macdonaldi), the Pacific sheath-tailed bat (Emballonura semicaudata) and the Fiji free-tailed bat (Chaerephon bregullae). Joanne Malotaux NatureFiji-MareqetiViti July 2012 Bat caves in Fiji Status and conservation of roosting caves of the Fiji blossom bat (Notopteris macdonaldi), the Pacific sheath-tailed bat (Emballonura semicaudata) and the Fiji free-tailed bat (Chaerephon bregullae). Report number: 2012-15 Date: 27th June 2012 Prepared by: Joanne Malotaux, intern at NatureFiji-MareqetiViti NatureFiji-MareqetiViti 14 Hamilton-Beattie Street Suva, Fiji Cover page picture: Wailotua cave. © Joanne Malotaux. 1 CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Chapter 1. Cave-dwelling bat species...................................................................................................... 4 Fiji blossom bat .................................................................................................................................... 4 Pacific sheath-tailed bat ...................................................................................................................... 5 Fiji free-tailed bat ................................................................................................................................ 6 Chapter 2. General recommendations ................................................................................................... -

Some Unintended Results of Blanket Cave Closures: a Story About Fern Cave Jennifer Pinkley

Some Unintended Results of Blanket Cave Closures: a Story about Fern Cave Jennifer Pinkley The first time I visited Alabama’s Fern Along the way, explorers found beauti- Grotto members about gray bats and the Cave, I thought of the Mines of Moria in ful and rare helictites, gypsum crystals that need to avoid disturbing them. The Grotto JRR Tolkien’s Middle Earth: vast beyond look like giant corn flakes, huge dogtooth started to get the word out that cavers should imagining. As I moved through the cave, it spar calcite formations, rimstone dams, stay out of the approximately three miles of seemed that around every corner I discovered towering flowstone, giant rooms, deep pits, Morgue passage of the cave in the winter. another passage, another canyon, another cave pearls, and stream passage. In obscure Cavers complied. The bats thrived. path to explore. On that first bewildering rooms, cavers found bones of extinct animals trip, I visited Helictite Heaven, one of the that roamed the earth over 13,000 years MAnAgeMent under tHe us FisH And most beautiful and bizarre rooms not only in ago, including giant-sized varieties of cave WiLdLiFe serviCe Fern, but in any cave I’ve ever visited. Weird bears, armadillos, and lions. Hidden in the In 1980, the US Fish and Wildlife rock forms sprout out of the floors, walls and mud were also jaguar teeth, a horse tooth, Service (FWS) purchased all of the entrances ceilings like mutant, sparkling coral bushes. and a 2,400-year-old human jawbone. to Fern, except Surprise Pit, to protect the After that trip, I was hooked. -

Site Management Plan, Medford District BLM

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Background ............................................................................................................................... 3 II. Life History .............................................................................................................................. 4 Habitat Associations ................................................................................................................... 4 Roosting Ecology ........................................................................................................................ 4 Foraging Behavior, Habitat, and Diet ......................................................................................... 6 Reproduction and Development ................................................................................................. 6 Behavioral ecology ..................................................................................................................... 7 III. Threats..................................................................................................................................... 7 IV. General Management Direction for Townsend’s Big-eared Bat Roost Sites ........................ 8 V. Grants Pass Resource Area Sites .......................................................................................... 10 Oak Mine .................................................................................................................................. 10 Gopher / Baby / Lamb Mine .................................................................................................... -

Agency Guide to Cave and Mine Gates 2009

Agency Guide to Cave and Mine Gates 2009 Jerry Fant, American Cave Conservation Association Jim Kennedy, Bat Conservation International Roy Powers, Jr., American Cave Conservation Association William Elliott, Missouri Department of Conservation Agency Guide to Cave and Mine Gates August 2009 Jerry Fant (ACCA) Jim Kennedy (BCI) Roy Powers, Jr. (ACCA) William Elliott (MDC) Sponsored by: American Cave Conservation Association Bat Conservation International Missouri Department of Conservation Contents: Introduction 1 Why gate? 2 Placement of gates and variations on the standard design 4 Gate Design Specifications 8 Construction timing 10 Gate Contractors 11 Post-gating Actions 12 Resources 13 Selected reading live 15 Introduction This guide is not intended to become a how-to manual on building gates to protect cave and mine resources, or to reduce liability at those sites, particularly abandoned mines. It is, however, intended to guide resource managers in making the best decisions on why, how, when, and who should build such gates. Over the years many hundreds, if not thousands, of gates have been constructed across the United States to secure cave and mine entrances. Some are good, being both secure and ecologically transparent. Others, poorly planned and designed, have had severe detrimental effects on the very resources they were built to protect. Over the years, much research by the American Cave Conservation Association, Bat Conservation International, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service has helped aid in the evolution of cave and mine gates, to the point where we now know what features are essential. An “industry standard” design with variations is now widely accepted by the National Park Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management, US Forest Service, NGOs such as The Nature Conservancy and the National Speleological Society, and many state wildlife agencies and conservation departments. -

High Resolution

2 CRF NEWSLETTER CRF Benefits from Amazon Volume 49, No. 3 Donation Program established 1973 Send all articles and reports for submission to: By: Bob Hoke, CRF Treasurer Laura Lexander, Editor Amazon.com now has a program, called Am- [email protected] azonSmile, that allows customers to specify a 21551 SE 273rd Ct., Maple Valley, WA 98038 charity that will receive a donation of 0.5% of the purchase price of many products purchased The CRF Newsletter is a quarterly publication of the Cave on Amazon.com. CRF is registered with Ama- Research Foundation, a non-profit organization incorpo- zonSmile so you can specify that CRF receive a rated in 1957 under the laws of Kentucky for the purpose donation if your purchase is eligible. The dona- of furthering research, conservation, and education about tion is made by Amazon and is not added to the caves and karst. cost of your purchase. Newsletter Submissions & Deadlines: CRF became part of the AmazonSmile pro- Original articles and photographs are welcome. If intend- gram in mid -2014 and as of May 2021, we have ing to jointly submit material to another publication, please received a total of $1,158 from it. The money is inform the CRF editor. Publication cannot be guaranteed, used to offset some of the Foundations adminis- especially if submitted elsewhere. All material is subject to trative expenses. revision unless the author specifically requests otherwise. To enable donations for your purchases, go For timely publication, please observe these deadlines: to Smile.Amazon.com instead of Amazon.com. The first time you will be asked to select a char- February issue by December 1 it y so just enter “Cave Research Foundation, May issue by March 1 Inc.” and select it. -

Annual Report

1985 ANNUAL REPORT c A v E R E s E A R c H F 0 u N D A T I 0 N Cave Research Foundation 1985 Annual Report Cave Research Foundation 1019 Maplewood Dr., No. 211 Cedar Falls, lA 50613 USA The Cave Research Foundation (CRF) is a nonprofit corporation formed in 1957 under the laws of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Its purpose is to support scientific research related to caves and karst, to aid in the conservation of cave karst wilderness features, and to assist in the interpretation of caves through education. EDITOR Karen Bradley Lindsley EDITORIAL STAFF R. Pete Lindsley John C. Tinsley Cover Photo: A typical remipedian crustacean as found in anchialine caves in the Bahamas. This photo of a live, swimming remipede shows the characteristic raptorial feeding appendages and a trunk with many similar segments, each bearing a pair of biramous swimming appendages. See report on page 21. (Photo by Dennis W. Williams). Cave Research Foundation 1985 Annual Report. © 1986 by the Cave Research Foundation. Permission is granted to reproduce this material for scientific and educational use. For information write to the Cave Research Foundation, 1019 Maplewood Dr. No. 211, Cedar Falls, lA, 50613 USA. ISBN 0-939748-19-3 P~blished by CAVE BOOKS 756 Harvard Avenue St. Louis, MO 63130 USA CAVE CONSERVATION The caves in which we carry out our scientific work and exploration are natural, living laboratories. Without these laboratories, little of what is described in this Annual Report could be studied. The Cave Research Foundation is committed to the preservation of all underground resources. -

Chapter 2. Cave Management Practices

II. CAVE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES By Daniel J. Neubaum, Cyndi J. Mosch, and Jeremy L. Siemers The use of subterranean features, such as caves, as bat roost sites is well documented. In the US, many species of bats rely on cave roosts as winter hibernacula, summer nurseries (Pierson 1998; Tuttle 2003), summer bachelor roosts, and migratory stopover sites between seasons, and for swarming activity in the fall (Parsons et al. 2003; Ingersoll et al. 2010). Swarming behavior in and around caves is an activity that is not well understood in western North America (Schowalter 1980; Navo et al. 2002), but could play an important social role for various bat species in Colorado. Consequently, caves are critical resources for bats and have been classified as “essential” for at least 18 species in the continental U.S. (McCracken 1989; Medellin et al. 2017). Caves also provide sites where unusually large aggregations of bats may occur, making the population more vulnerable to disturbance than in other settings (Sheffield et al. 1992). Threats to cave-dwelling bats include disturbances from recreational activity in and around roosts, cave development for tourism and guano mining, improper cave gate design, inappropriate or excessive scientific research (e.g., excessive banding of bats and general disturbance by researchers during critical time periods; Rabinowitz and Tuttle 1980; White and Seginak 1987; Richter et al. 1993; Tuttle 2000; O’Shea et al. 2004), and, more recently, the introduction of White Nose Syndrome (WNS; see chapter VII. Bats and Disease). Direct disturbance to suitable cave roosts can be a serious threat and has resulted in the listing of several bat species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA; USFWS 1976), and population declines of more common taxa (O’Shea and Vaughan 1999). -

Mike Warton & Associates Geologist / Karst Terrains

MIKE WARTON & ASSOCIATES GEOLOGIST / KARST TERRAINS SPECIALISTS / NATIONAL CAVE GATE CONSULTANT P. 0. BOX 1313 CEDAR PARK, TEXAS 78613 - 1313 AC (512) 250 - 0705 * FAX: (512) 250 - 0706 *** SPECIALISTS IN TEXAS ENVIRONMENTAL KARST RESEARCH & SERVICES ··*** A PRELIMINARY " REPORT OF FINDINGS " FOR: THE KARST TERRAINS FEATURE KNOWN AS " RUGH " CAVERN, LOCATED ALONG NORTHERN " SECO " CREEK, NORTHWESTERN MEDINA COUNTY, TEXAS. DATE: AUGUST 23, 1993 PERPARED FOR: THE EDWARDS UNDERGROUND WATER DISTRICT ( E. U. W. D. ) 1615 NORTH ST. MARYS, P.O. BOX 15830 SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS 78212 - 9030 . ATTN: MR. ROBERT BADER: THE " GATING " AND EXPLORATION OF " RUGH " CAVERN ' MEDINA COUNTY, TEXAS. A Preliminary Report by: Mike Warton AUGUST 23, 1993 Introduction: In March of 1993, I recieved a phone call from the EDWARDS UNDERGROUND WATER DISTRICT (E.U.W.D.) in San Antonio, Texas. This call was about a Medina County Rancher who had requested need for a Cave Gate to be placed over a mysterious hole in the bed of " SECO " Creek approx. 1.5 Miles upstream of The " Valdina Farms Sinkhole " Area. The Land owners concern was to prevent a loss of life/ or cattle from being sucked down into this Feature during periods of Insurging Recharge. Naturally, I found that my ears were still firmly attached to my curiousity. I believe my only reply was •••• " When do we go "? Was this a known Cave? Where exactly is this again? Upstream from Valdina Farms Sinkhole •.•.• How far? Was it perhaps " Rote " Cave? No, He said the entrance was in the bed of the Creek! Hummm •••••••••••••• My mind drifted off into the past to the time of my only visit to Valdina Farms Sinkhole. -

Colorado Bat Conservation Plan Second Edition

COLORADO BAT CONSERVATION PLAN SECOND EDITION Prepared by: The Colorado Bat Working Group The Colorado Committee of the Western Bat Working Group By K.W. Navo, D.J. Neubaum, and M.A. Neubaum (Editors) March 2018 Colorado Bat Conservation Plan 11/17/2020 Western Bat Working Group, Colorado Committee Page i of 204 Suggested Citation: Navo, K.W., D. N. Neubaum, and M.A. Neubaum, eds., 2018. Colorado bat conservation plan. Second Edition. Colorado Committee of the Western Bat Working Group. Available at the Colorado Bat Working Group webpage (http://cnhp.colostate.edu/cbwg/consPlan.asp). Colorado Bat Conservation Plan 11/17/2020 Western Bat Working Group, Colorado Committee Page ii of 204 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................................................................. V INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 CONSERVATION STRATEGY........................................................................................................................................... 7 I. MINING IMPACTS ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 INADEQUATE KNOWLEDGE OF BAT DEPENDENCE ON MINES ................................................................................................ 11 RENEWED AND ACTIVE MINING PRACTICES