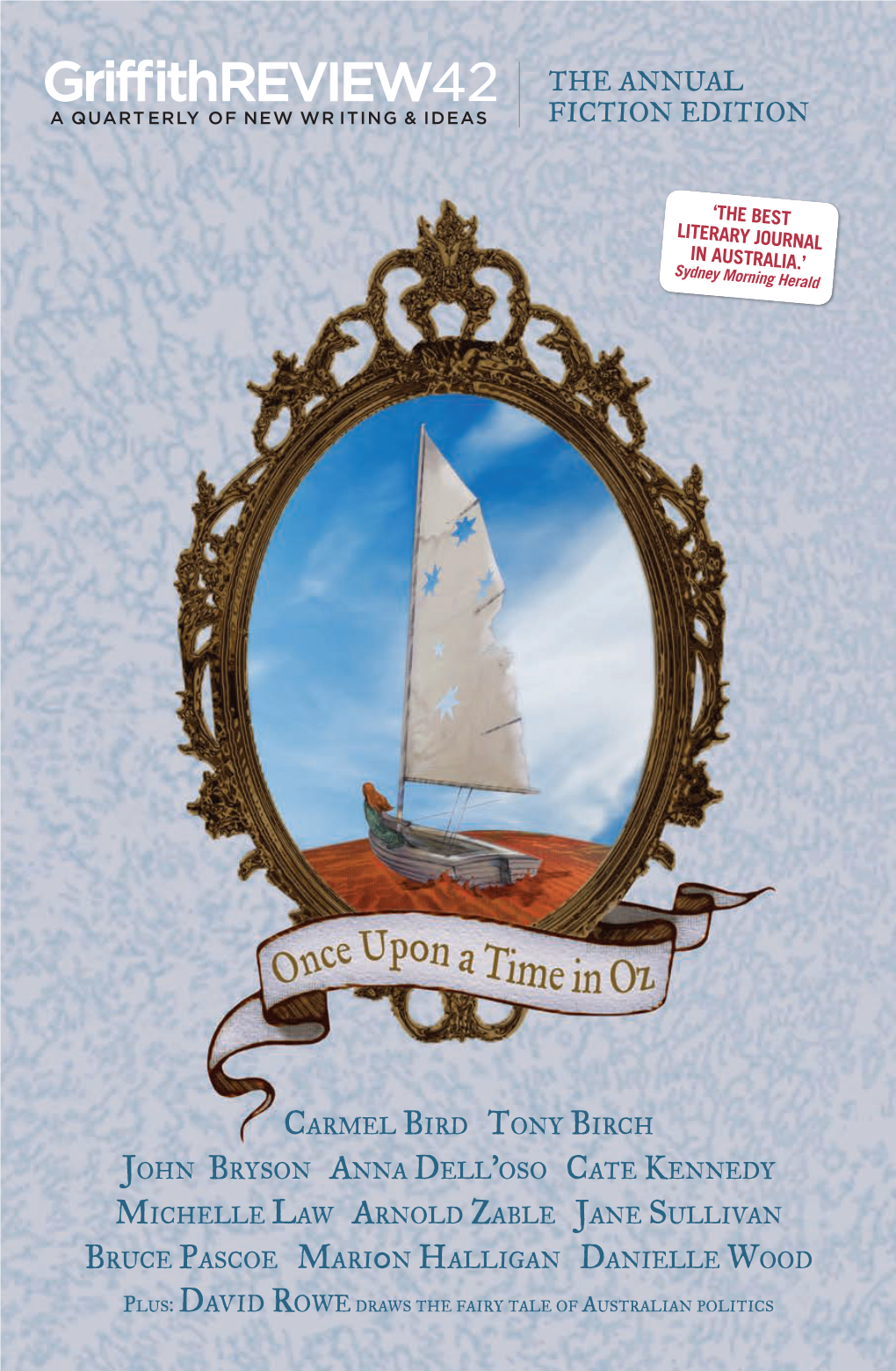

Griffith REVIEW Edition 42

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Makeup-Hairstyling-2019-V1-Ballot.Pdf

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Hairstyling For A Single-Camera Series A.P. Bio Melvin April 11, 2019 Synopsis Jack's war with his neighbor reaches a turning point when it threatens to ruin a date with Lynette. And when the school photographer ups his rate, Durbin takes school pictures into his own hands. Technical Description Lynette’s hair was flat-ironed straight and styled. Glenn’s hair was blow-dried and styled with pomade. Lyric’s wigs are flat-ironed straight or curled with a marcel iron; a Marie Antoinette wig was created using a ¾” marcel iron and white-color spray. Jean and Paula’s (Paula = set in pin curls) curls were created with a ¾” marcel iron and Redken Hot Sets. Aparna’s hair is blow-dried straight and ends flipped up with a metal round brush. Nancy Martinez, Department Head Hairstylist Kristine Tack, Key Hairstylist American Gods Donar The Great April 14, 2019 Synopsis Shadow and Mr. Wednesday seek out Dvalin to repair the Gungnir spear. But before the dwarf is able to etch the runes of war, he requires a powerful artifact in exchange. On the journey, Wednesday tells Shadow the story of Donar the Great, set in a 1930’s Burlesque Cabaret flashback. Technical Description Mr. Weds slicked for Cabaret and two 1930-40’s inspired styles. Mr. Nancy was finger-waved. Donar wore long and medium lace wigs and a short haircut for time cuts. Columbia wore a lace wig ironed and pin curled for movement. TechBoy wore short lace wig. Showgirls wore wigs and wig caps backstage audience men in feminine styles women in masculine styles. -

Northern Territory Emergency Response: Report of the NTER

NORTHERN TERRITORY EMERGENCY RESPONSE REPORT OF THE NTER REVIEW BOARD October 2008 i © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth available from Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney-General’s Department. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Commonwealth Copyright Administration Attorney-General’s Department Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit Canberra ACT 2600 or posted at www.ag.gov.au/cca First published October 2008. Produced by the Australian Government. Disclaimer The opinions, comments and /or analysis expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs or the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, and cannot be taken in any way as expressions of government policy. ii JENNY MACKLIN MP Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Dear Minister The Board would like to present our report reviewing the Northern Territory Emergency Response, in accordance with our Terms of Reference, issued on 6 June 2008. We thank you for the privilege of undertaking the review and offer our report in the sincere hope that it will assist the Australian Government to improve the safety and wellbeing of Aboriginal children -

Virtually Bi Edges No Oiaiige Iii Strategy

Tt^=7l ■' v . .■ X' The Wflflther ■ATU10AX, A rm . 14 iM i A v e riffl Dally Clrenlatfon Fcrecaat of-L'. S. Weather Mi^ichesiery Evening Herald For the Month at M a td li^ m s — 1 _______________ , i f ” i ' I ..- Rafn tonight hqd Tuesday mom- / r nXpn a winter coat and fur collar 'bun-' ' 9 , 1 5 8 In afternoon W gh *^ died atx>ut bar neck. Indicating tempemturea WiiM Bronze Star First Wteriu^s WALTER SCHULTZ I A m aldarilaa balfava in tak Member ot.ttM Audit ‘AboiTt T qw u L o ^ H^ro Dead Heard Along 'Main^^treet that 82 CoaCTCM StVMt ing ^no chancaa with thlf,,jiyjtuaual Baraan at ClkpBlstloaa ■ \ April weather, while the teen-, Mancitester-^A City of Village Charm V tli^ e Plapii^ agera Walk along confldentljr with Ashes and l^nbbish Tha B*lv««on Amjy Women'i And on Some of H^heeter\Side Too PRICE: e W k d :E N T 3 out fear of catching cold. (TWELVE PAGES) Homa Laaj^a will ba in charge ef Tlemoved T ^ S*15881 MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, APR IL^16, 1945 tha Braifrain Jthis avening at 8 A l^ d e r who was In Forest ^ of Bolton. up a stiff sYi filia l One Here/^nder VOL. LXir.,Vo. 166 ’elo^M lt the clUdel; of vocar and Park, Springfield, last Sunday J to conve: the mess serge' Remember the mid-May apple inat^umental miielc and readings, brings back a story of profiteering hU cooking ways blossom fetes they used to stage G. -

Contemporary Carioca: Technologies of Mixing in A

Con tempo C o n t e m p o r a r y raryC a r i o c a Cari oca ontemporary CCarioca Technologies of Mixing in a Brazilian Music Scene Frederick Moehn Duke University Press Durham anD LonDon 2012 © 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ♾ Designed by Kristina Kachele Typeset in Quadraat and Ostrich Sans by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Stony Brook University, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. For Brazil’s musical alchemists ontents Illustrations ix C Preface xi Acknowledgments xxiii Introduction 1 1 Marcos Suzano: A Carioca Blade Runner 25 2 Lenine: Pernambuco Speaking to the World 55 3 Pedro Luís and The Wall: Tupy Astronauts 92 4 Fernanda Abreu: Garota Carioca 130 5 Paulinho Moska: Difference and Repetition 167 6 On Cannibals and Chameleons 204 Appendix 1: About the Interviews, with a List of Interviews Cited 211 Appendix 2: Introductory Aspects of Marcos Suzano’s Pandeiro Method 215 Notes 219 References 245 Discography 267 Index 269 llustrations Map of Rio de Janeiro with inset of the South Zone 6 1 “mpb: Engajamento ou alienação?” debate invitation xii 2 Marcos Suzano’s favorite pandeiro (underside) 29 I 3 Marcos Suzano demonstrating his pandeiro and electronic foot pedal effects setup 34 4 A common basic samba pattern on pandeiro 48 5 One of Marcos Suzano’s pandeiro patterns 49 6 Marcos -

SIHHHDS304A Design and Apply Classic Long Hair up Styles

SIHHHDS304A Design and apply classic long hair up styles Release: 1 SIHHHDS304A Design and apply classic long hair up styles Date this document was generated: 26 May 2012 SIHHHDS304A Design and apply classic long hair up styles Modification History Not applicable. Unit Descriptor This unit describes the performance outcomes, skills and knowledge required to create classic long hair design finishes on a range of clients. Application of the Unit This unit applies to hairdressers in salon environments, who apply classic finished up-style designs to long hair on female clients. A person undertaking this role applies discretion and judgement and accepts responsibility for outcomes of own work. Licensing/Regulatory Information No licensing, legislative, regulatory or certification requirements apply to this unit at the time of endorsement. Pre-Requisites Nil Employability Skills Information This unit contains employability skills. Approved Page 2 of 9 © Commonwealth of Australia, 2012 Service Skills Australia SIHHHDS304A Design and apply classic long hair up styles Date this document was generated: 26 May 2012 Elements and Performance Criteria Pre-Content Elements and Performance Criteria ELEMENT PERFORMANCE CRITERIA Elements describe the Performance criteria describe the performance needed to essential outcomes of a demonstrate achievement of the element. Where bold italicised text unit of competency. is used, further information is detailed in the required skills and knowledge section and the range statement. Assessment of performance is to be consistent with the evidence guide. 1. Analyse client 1.1. Establish natural hair type, texture, growth patterns, characteristics. length, structure and movement by physical and visual examination. 1.2. Observe facial features and bone structure. -

The Impact of World War II on Women's Fashion in the United States and Britain

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 12-2011 The impact of World War II on women's fashion in the United States and Britain Meghann Mason University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, European History Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Mason, Meghann, "The impact of World War II on women's fashion in the United States and Britain" (2011). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1390. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/3290388 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF WORLD WAR II ON WOMEN’S FASHION IN THE UNITED STATES AND BRITAIN By Meghann Mason A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements -

Course Preview Brochure Certification Course

COURSE PREVIEW BROCHURE Hair Styling Essentials CERTIFICATION COURSE The Hair Styling Essentials Course is perfect for beginner stylists and established makeup artists who want to expand their skillset and range of services. You’ll start with the fundamentals and advance your skillset so you’ll be able to work with brides and on photoshoots and movie sets! Turn your passion for hair styling into practical skills, and become a certified hair stylist! When you take the course you’ll gain… • A world-class education that prepares you to work in cities such as London, New York, Sydney, Vancouver—and even your hometown! • The technical skills to create beautiful blow-outs, updos and period looks for brides, models and actors. • The confidence to turn your passion into a rewarding career “Loving QC Academy! Just submitted my final unit in Master Makeup and still getting through Hair Styling, Airbrush, and then onto Pro Makeup. I’ve already started getting clients and am booked up 3 weeks in advance! None of this would have been possible without QC Academy, and I’ve only been doing the course for a couple of months!” Katie Harris Hair Styling Essentials Graduate Once you graduate, you’ll receive your Hair Styling Essentials certificate. You’ll be ready to start your business and work in the industry right away! “I’ve just started, but I have to say the materials and videos are excellent and full of details. You can even watch it anytime and anywhere. I can’t wait to finish Master Makeup Artistry and the Hair Styling course. -

Read Hair Tutorial Video Transcript

00.00 From one house of isolation, to another Hello! With the 75th anniversary of VE day being upon us unfortunately, all of the events that would have been scheduled to happen 00.10 to celebrate this amazing occasion, of course, have been cancelled. So, in, er, trusty social distancing styling goodness I thought it would be a good time to show you 00.20 quite a - hopefully - simple tutorial for all you long-haired-ladies, or long-haired-men to embrace this very iconic style. 00.30 But first, let's wind back and take a look at the history. [Voiceover] The origin of the victory roll hairstyle is somewhat blurry. Though there is an incredibly romantic theory that claims to shed light on this. 00.40 During World War II, ladies were enrolled into the workforce and after several hair related machinery accidents it became mandatory that hair must be pinned up whilst working. 00.50 While the women were working in factories the men were flying into battle. On completion of a mission, and as a sign of victory fighter pilots would perform an aerobatic manoeuvre 01.00 in the sky, which would cause their exhaust smoke to make a rolling pattern. Similarly to how you might see the red arrows when they perform today. 01.10 It was this that inspired patriotic women to honour their returning soldiers, by adopting the name for this pinned up hairstyle. Which was seen widely across factory workers 01.20 as well as every day fashion and day to day life. -

Hairdressing Training Manual New Zealand Certificate in Hairdressing (Professional Stylist) Level 4

Hairdressing Training Manual New Zealand Certificate in Hairdressing (Professional Stylist) Level 4 www.hito.org.nz © Copyright 2016 New Zealand Hair and Beauty Industry Training Organisation Introduction Introduction Welcome 2 Training expectations 3 Training resources 4 Training tips 5 Assessment 8 Learning 9 Workplace behaviour guidelines 11 The HITO team 12 Training Requirements 15 Unit Standard Guides Year one 23 Year two 85 Year three 137 Year four 175 1 Introduction Welcome Congratulations on taking on a HITO hairdressing apprentice. This is your training manual. It contains general training advice and specific activities to help your apprentice learn. The hairdressing qualification is made up of unit standards which cover the skills your apprentice needs to know. The manual goes through each unit standard, starting with the easiest ones and working up to harder ones. You should work through the units in the order they appear in the training manual. You’ll also notice that the unit standards in this book are divided by year level. It should take no more than 12 months to complete the units in each year. Your apprentice must complete all the units in a year level before moving onto the next year level. There is a glossary at the back to explain any words your apprentice doesn’t understand. This manual contains advice on training in general, how HITO training works, and who to ask for help if you need it. This information is in the Introduction section. Keep this manual at the salon at all times. You’ll need to refer to it often when training, and your HITO Sales and Liaison Manager may need to see it when they visit. -

Portland Daily Press: September 01,1880

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. - ESTABLISHED JUNE 1862.—YOL. 18. 23, PORTLAND, WEDNESDAY MORNING, SEPTEMBER 1, 1880. |&H3ia&,iSBSS| PRICE 3 CENTS. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, The renewed energy of the Democratic MISCELLANEOUS APPOINTMENTS. A Disbanded Ficumxti oil the is a favorite THE U but the Army. majority Published every d«y (Sundays excepted) by the PRESS. parly spasmodic effort that The action amusement now. That is fnn; but CHASE’S MEETING HOUSE, Wednesday Even- presages death. From this national taken by Messrs. Gove and good PORTLAND PUBLISHING CO*, better for WEDNESDAY HORNING, SEPT. 1. ing, Sept. 1. struggle it will fall back, a defeated, dis- Denison and others, in withdrawing from fun is to put in work that majori- A.T 109 ExcttAjTOK Pobtlaxd. FALMOUTH FORESIDE, 2. cordant nnd St., Thursday, Sept. hopeless minority. The hope the Greenback organization, is having great ty. We want to laugh last and if we waste BRUNSWICK, (New Meadows School House.) of federal Tekmb : Eight Dollars a Tear. To mall eubscrlb- communi- patronage gone, its local su- and too much time is We do no t read anonymous letters and immediate effect upon Maine Green- in hilarity now there a pos. ars Seven Dollars a Tear, 11 paid in advance. GOING Friday, Sept. 3. premacies cannot be maintained. FAST. are in long cations. The name and address of the writer backers who that the Democratic bull on the CAPE ELIZABETH, Saturday, Sept. 4. This is to be were once Republicans and sibility for desired, for the way to cur- THE MAINE“STATE PRESS all cases Indispensable, not necessarily publica- whose other side of tlie fence will have the NORTH HARPSWELL, Monday, Sept. -

Find Happiness Borough Officials Accesschle A

; $80,000 Washroom Building For USMR Workers $500 Red Cross DPs Quickly Adjust to New]artcrct,Township •oiif[hCI,n. Donation Is Made Environments; Find Happiness Are Planning Talk CARTER ET-More than 100 Interviews with some of the r(,a Casualty By Foster Wheeler European displaced persons, vic- DP'.s indicated that the period tims of the last war. are suc- On Sewer Problems of adjustment for these people cessfully resettled in this bor- Street Youth is extremely hard. Uck of Eng- erf Additional $200 Gift ough. Borough Official* Ot ,.,1, Recovteripg Received From USMR, Nearly all of them are gain- lish language, the uhf.imlllarltj' Mill' fully employed without havlnu with American ways o! Ufa and Invitation to Attend Japan Hospital Kaplan Report* displaced a single American habits mid strangeness of our Township from hia occupation or his ' ,,,,-[.•_'.; pfc. Arthur 0. economic system have been the CARTERET—Donations to the home, a survey reveals. ""• n, son of Ur. Md crrief handicaps. CARTBRKT—Borough Attorney 1951 Red Cross fund drive In Car- The great achievements In "'.', ,} Stewart, 37 Mercer . W. Harrington revealed today tcret today reached the $2,000 resettlement accomplished thus Yet, the majority of these A! imwn with the Twenty- hat Carteret has rctdvrd nnd marks, a far cry (rom the $4,500 far were made possible through "new Amerlcuns" hive succeed- 1 •'' "...iiiry Regiment, was accepted an Invitation from the Roal set for the borough. the untiring cflorU and close ed In a comparatively short time ", ' 'KOU March 8. the Township to sit In at n meeting In a special report, Samuel Kap- cooperation of the various Car- to overcome them •fy'pl.p.rtment has notified of the Township Committee in an lan, general chairman, announced teret leaders and the U. -

The 5 Best Hairstyles for Your Boudoir Shoot

The 5 Best hairstyles for your boudoir shoot Let’s face it, hair is important. It wouldn’t be a fast growing 4.8-billion-dollar industry in Australia if us women weren’t fussed, would it? With that in mind, we asked our stylist to give us some advice on the best way to wear our hair for our boudoir shoot and she’s given us The 5 Best Boudoir Hairstyles for you to try out for yourself! Which do you think you would rock at your shoot? 1)Loose curls It’s definitely the all-time favourite hair style of the studio and works for playful, tousled looks as well as refined and classy portraits as well. Although it might take a bit of effort to get those curls in there, we always think it’s worth the effort and works especially well for women who naturally have long straight hair who want to keep it down but want a slightly different look to what they’re used to. It can be equally beneficial for women who have a bit of root growth as the texturing in the hair lessens the effect! 10/10 every time. 2) Coloured hair Similar to its’ skin counterpart, we think coloured hair really makes photos pop, and in a boudoir shoot it can also be a great way to tie together an outfit! It may even add just that splash of colour in an otherwise neutral image which creates real drama. Although coloured hair can require a fair bit of maintenance, the photos last forever, so we figure it’s definitely a worthwhile investment! We also love clients that come in with beautiful colour in their hair because it’s just a little bit different, and the best boudoir shoots are always the ones that were personalised by lingerie, tattoos, character and accessories! 3) Straight and sleek Again, for women who have naturally curly hair, it may be a great opportunity to wear a slightly different look to go with your sexy alter ego.