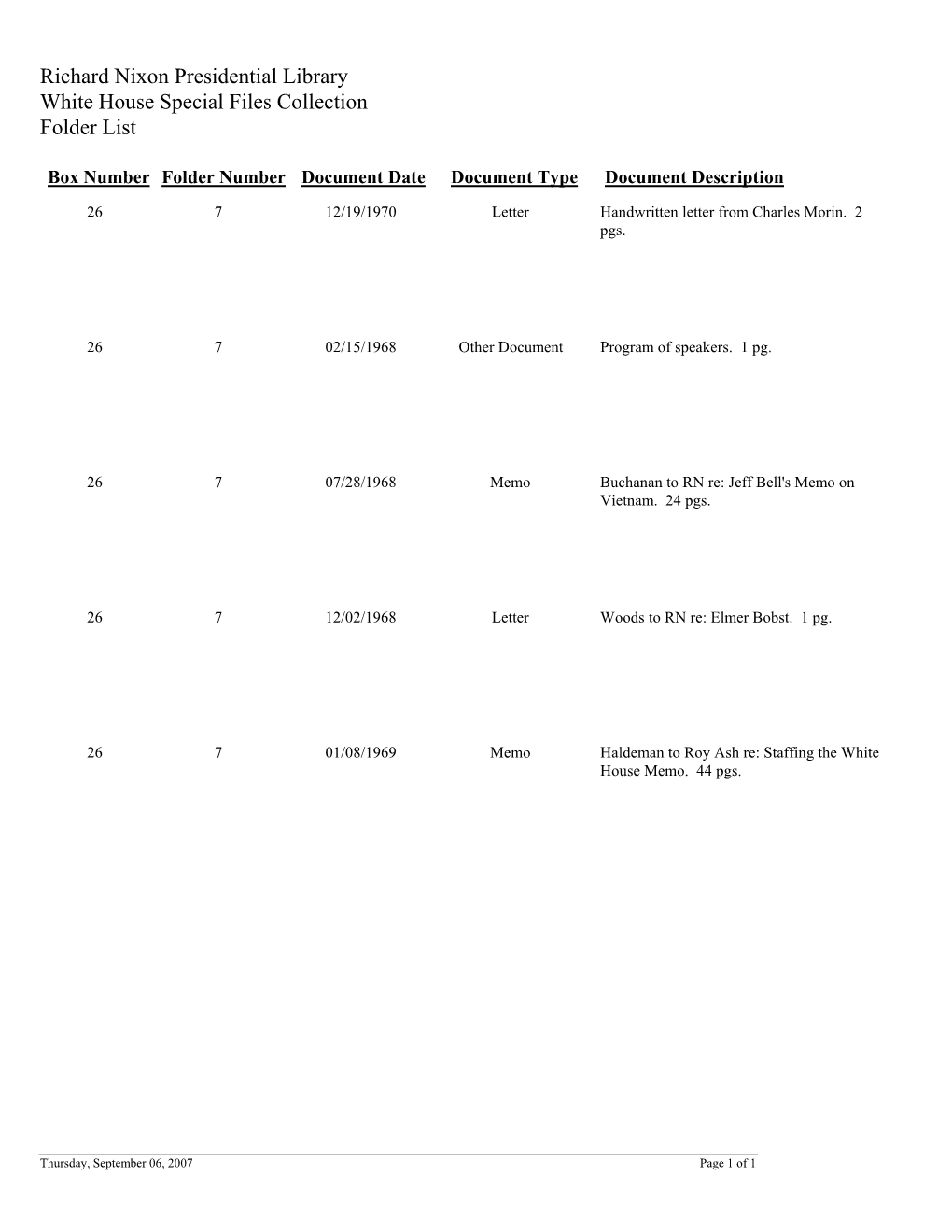

White House Special Files Box 26 Folder 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9/20/78 President's Trip to New Jersey

9/20/78-President’s Trip to New Jersey [Briefing Book] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 9/20/78- President’s Trip to New Jersey [Briefing Book]; Container 91 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) " " FORM OF DATE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT CQRRESPONDENTS OR TITLE Briefin~ Book Page Page from Briefing Book on NJ Trip, 1 pg., re:Political overview c.9/20/ 8 C ' • o" J .t. ' 'I " j '' ;~o.: I. '"' FILE LOCATION Carter Presidential Papers-Staff Offices, Office of Staff Sec.-Presidential Handw·riting File, PreS,i,dent's Trip to NJ 9/20/78 [Briefing Book] Box 102 ~ESTRICTION CODES ' (A) Closed by Executive Order 12356'governing access to national security information. (B) Closed·by statute or by the agency which originated the document. (C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gift. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION. NA FORM 1429 (6-8•5) " \ ) , THE WHITE HOUSE WASH'INGTON THE PRESIDENT'S VISIT TO ATLANTIC CITY, NEWlJERSEY·. '~ednesday, September: 20, 1978 ·.' <'':. .· ' . ~- WEATHER REPORT: Fair and mild, temperatures from low 50's to mid-60's. .... ... 8:.45 am, GUEST &: STAFF INSTRUCTION: The ·following are to be in the Disting~ished Visitor's Lounge at Andrews AFB to subsequently board Air Force One. Secretary Ray MarshaH . Sen. and Mrs. Harrison Williams (Jeannette) (D-N •. J.) Sen. Clifford Case (R-N .J .) Rep. Helen Meyner (D-N. J.) Rep. James Florio (D-N .J.) Rep. William Hughes (D-N. -

Krista Jenkins 973.443.8390 Or [email protected] BLAST FROM

For Immediate Release, Tuesday, October 21 9 pages Contact: Krista Jenkins 973.443.8390 or [email protected] BLAST FROM THE PAST: LEAD FOR BOOKER COMPARABLE TO BELL’S LAST OPPONENT IN 1978 November’s Senate election pits the incumbent, Democrat Cory Booker, against an underdog, Republican Jeff Bell. While most are focused on the horserace numbers between the two, Fairleigh Dickinson University’s PublicMind expands the focus by asking likely voters not just about the current contest involving Bell, but also their preferences in a hypothetical rematch between Bell and his 1978 opponent, Democrat Bill Bradley. Beginning with how Bell fares against his current opponent, the poll finds that Booker’s lead remains formidable at 56 to 40 percent, with Booker outpacing Bell’s favorables by an almost two-to-one margin (57% versus 29%, respectively). Despite Bell’s history in New Jersey politics, voters remain unsure of their opinion of him (49%). “Since the interviews were done more than two weeks out from the election, numbers are certainly likely to change. But a lead of this magnitude is good news for the incumbent Senator,” said Krista Jenkins, director of the poll and professor of political science. “It’s not a political environment that’s particularly warm for incumbents, but it looks like Booker has little to be worried about as the campaign season draws to a close.” The same poll finds that Bell polls worse now than 35 years ago when he first ran for a New Jersey U.S. Senate seat and lost. In a hypothetical rematch between Bell and then-competitor Bradley today, PublicMind pegs him at 36 percent whereas in 1978 he wound up with 43 percent of the vote. -

BUSINESS Arms Freeze Just Soviets Seem Uneasy How to Sell |One Joyner Cause About Arms Talks Your House Nail Down Maximum in Deductions! F'f

20 - MANCHESTER HERALD, Tues., June 1, 1982 BUSINESS Arms freeze just Soviets seem uneasy How to sell |one Joyner cause about arms talks your house Nail down maximum in deductions! f'f . page 3 . page 10 . page 25 1 deduction. of his lodging while he’s at home. If he’s at home for With the fall semester’s college costs already making 3) “ M y daughter w ill earn around $2,600 this summer. four months plus what you spend for college expenses a nightmare out of the summer vacation to come, this is I expect to provide another $2,400 in support in ’82. So I could put you w ell over the more-than-half mark. _ • Fair, cool tonight: the time to look for ways the tax law might help you If you provide a car, arrange the financing yourself Manchester, Conn. Your flunk the more-than-half support test.” « sunny on Thursday take some of the nightmare out of this era’s soaring Wrong! You may save your dependency deduction and make a small down pasunent, this capital expen Wednesday, June 2, 1982 costs. You can get a $1,000 dependency deduction for Money's because of an often-overlooked tax rule. Money your diture may count as support for your child. Make a gift — See page 2 your child in college as long as you provide more than daughter earns doesn’t necessarily all count as support of the car and have your son register it in his name.] Single copy 25c half of his or her support. -

Ohio's #1 Professor

THE MAGAZINE OF OHIO WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY Spring 2016 OHIO’S #1 PROFESSOR Eco-Scientist Laurie Anderson Expands the Classroom PagePage 12 12 4 Moot Court 18 Conventioneers 26 Art and 30 Record Conquerers Since 1884 Artifice Championships Elliott Hall at sunrise. Photo by Larry Hamill. 12 18 26 Features 12 Breaking Boundaries Named the 2015 Ohio Professor of the Year, Laurie Anderson is on a quest to solve 21st-century problems. Her method? Engage students to be part of the solution. 18 Conventional Wisdom No doubt about it—presidential nominations raise spirited debate. A century-plus tradition, Ohio Wesleyan’s Mock Convention brings its own political fervor every four years to OWU’s Gray Chapel. 26 Art & Artifice Retiring theatre professor Bonnie Milne Gardner and her former student—Anne Flanagan— reunite to showcase one last play. This time, it’s Flanagan’s award-winning “Artifice” that takes center stage at the Studio Theatre. Departments 02 LEADER’S LETTER 10 COMFORT ZONES 36 CALENDAR 04 FROM THE JAYWALK 30 BISHOP BATTLES 37 FACULTY NOTES 07 OWU TIMESCAPES 32 ALUMNI PROFILE 38 CLASSNOTES 08 GIFTS AND GRATITUDE 34 ALUMNI HAPPENINGS 48 THE FINAL WORD ON THE COVER: Professor of Botany-Microbiology Laurie Anderson in her element at the Moore Greenhouse. Cover photo: Mark Schmitter ‘12 2 | OWU Leader’s Letter CIVIC – AND CIVIL – ENGAGEMENT Arneson Pledge needed more than ever n February Ohio Wesleyan students, home state of Arkansas, where Melissa reasoned reflection. Students and faculty I faculty, and staff gathered in Gray and I were joined by OWU Trustee and deliberated with one another and shared Chapel to continue a tradition that Delaware County Commissioner Jeff the convention floor as equals. -

Note, to Dick Cheney

The original documents are located in Box C34, folder “Presidential Handwriting, 1/27/1976” of the Presidential Handwriting File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box C34 of The Presidential Handwriting File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON January 21, 1976 IMPORTANT MEMORANDUM FROM PETER KAYE.-~~......... I thought you'd all like to know how the other half lives . • ·.. }~ ~r j.1i\~ ~LJJ ~ca .· C/ 11 January 23, 1976 I Issue Number 131 THE BODY POLITIC: Behind the Reagan Campaign/A special report by the Political Animal's Washington correspondent What emerges from the opening weeks of Ronald Reagan's Presidential campaign is that the former California governor has failed to make the transition from banauet orator to serious Presidential candidate. Reagar must share part of the blame, owing to his procrastination and indecisive ness during 1974 and much of 1975. His own preoccupation with the lucrative speaking circuit, radio shows and columns - reinforced by the interest of his former Sacramento staffers, Mike Deaver and Peter Hannaford - froz~ out many important political contacts. -

![Convention Speech Material 8/14/80 [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5369/convention-speech-material-8-14-80-1-1455369.webp)

Convention Speech Material 8/14/80 [1]

Convention Speech Material 8/14/80 [1] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: Convention Speech material 8/14/80 [1]; Container 171 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf . �- . "". ·· . · : . .... .... , . 1980 · DEMOCRATIC PLATFORM SUMMARY .··.. · I. ECONOMY··. Tliis was·· one.of ·the mOst .. dfffibult sections to develop in the way we. wan:ted,.>for there wei�· considerable ··.support among the Platform committee .members for a,' stronger·· ant-i�recession program than we have 'adopted. to date·. senator :Kennedy's $1.2.·bili'ion'·stimulus ·prOpof>al was v�ry · attraeffive to ·many .. CoiiUJlitte.e ine.�bers, but in the . end •We were able to hold our members.' Another major problem q()ri.cerned the frankness with which· we wanted to recognize our current ecohomic situation. we ultimately .decided, co:r-rectly I believe, to recognize that we are in a recession, that unemployment is rising, and that there are no easy solutions.to these problems. Finally, the Kennedy people repeatedly wanted to include language stating that no action would be taken which would have any significant increase in unemployment. We successfully resisted this .by saying no such action would be taken with that .intent or design, but Kennedy will still seek a majority plank at the Convention on this subject. A. Economic Strength -- Solutions to Our Economic Problems 1. Full Employment. There is a commitment to achieve the Humphrey�Hawkins goals, at the cu�rently pre scribed dates. we successfully resi�ted.effdrts:to move these goals back to those origiilally ·prescribed· by this legislation. -

Dr. Hector P. Garcia: a Study in Cross-Cultural Communication Leadership

DR. HECTOR P. GARCIA: A STUDY IN CROSS-CULTURAL COMMUNICATION LEADERSHIP A Thesis by ROSANA VANESSA GOMEZ PACHON MBA, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, 2015 BS, Santo Tomas University-Colombia, 2007 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in COMMUNICATION Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Corpus Christi, Texas May 2020 © Rosana Vanessa Gomez Pachon All Rights Reserved May 2020 DR. HECTOR P. GARCIA: A STUDY IN CROSS-CULTURAL COMMUNICATION LEADERSHIP A Thesis by ROSANA VANESSA GOMEZ PACHON This thesis meets the standards for scope and quality of Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi and is hereby approved. Anantha Babbili, PhD Michelle M. Maresh-Fuehrer, PhD Chair Co-Chair May 2020 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to investigate the communication leadership styles of Dr. Hector P. Garcia, a Mexican American leader in the United States. Dr. Garcia is best known for founding the American G.I. Forum social movement with a mission to protect and defend veterans’ and Hispanic Americans’ civil rights by providing access to education, health, and employment. Trait, skills, and emotional intelligence leadership styles are applied using a critical rhetorical approach. Dr. Garcia’s leadership style is a reference to analyze, understand, and apply the different concepts, theories, and approaches concerning effective leadership. The results of this study demonstrate that Dr. Hector P. Garcia was a transformational and servant leader who used charismatic and authentic communication to build a relationship with followers. These findings illustrate how Dr. Garcia used different tools of persuasion such as ethos, logos, pathos, and civic spaces to deliver and engage in communication with his followers. -

Goo.P. Right Wing Seems to Rule out Support for Ford for 1976 Campaign

b A NYTimeg FEB 1 0 1975 dIVDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 1975 GoO.P. Right wing Seems to Rule Out Support for Ford for 1976 Campaign By CHRISTOPHER LYDON meanwhile, is using words such ing. Under comparable cross Special rto The New York Times as "awful," and "dangerous" to pressures to address the Water- WASHINGTON, Feb: 9 - characterize the Ford Adminis- gate issue at the conservatives' Leaders of the conservative tration budget deficits. convention a year ago, Mr. Re- movement in Republican poli- 9Human Events and its right- gan refused to attack President tics are talking about campaign wing columnists sound increas- Nixon, strategy for 1976, seemingly ingly alarmed about the Ford `Waiting for Regan' with scarcely a thought of sup- Administration. "There is no se- rious evidence that the Presi- Mr. Phillips said. "If he gives porting President Ford as a us a flag-waving speech as he candidate. dent is determined to reverse the explosive growth of gov- did last year, a lot of us will Most of them guess Mr. Ford be ready to give up on him. will not be running, in which ernment spending," the paper concludes in its upcoming is- What he's got to du is strike case they foresee an easy vic- a balance between being suffi- tory by former-Gov. Ronald sue. "It's a little early," says ciently critical and being fair. Reagan of California over Vice the Human Events editor, Thom- And he'sgotto give some hint President Rockefeller for the as S. Winter, "but the chances he's going to be a part in the party's nomination. -

Booker in 2014 Nj Senate Pole Position

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Contact: PATRICK MURRAY Please attribute this information to: 732-263-5858 (office) Monmouth University/ Asbury Park Press Poll 732-979-6769 (cell) [email protected] For more information: Monmouth University Polling Institute West Long Branch, NJ 07764 Released: www.monmouth.edu/polling Monday, March 3, 2014 BOOKER IN 2014 NJ SENATE POLE POSITION Potential GOP opponents unknown to voters Cory Booker’s only been on the job for a few months, but New Jersey voters seem ready to re-up his U.S. Senate contract for another six years. The Monmouth University/Asbury Park Press Poll finds the state’s junior senator enjoys growing approval ratings while the field of potential Republican opponents is largely unknown. Currently, 47% of New Jersey voters approve of the job Booker is doing as U.S. Senator compared to just 20% who disapprove. Another 32% have no opinion. In December, his job rating stood at 37% approve to 21% disapprove and 43% with no opinion. Booker took office in October, shortly after winning a special election to fill the remainder of the late Frank Lautenberg’s term. Booker garners solid ratings among his fellow Democrats (66% approve to 9% disapprove), generally positive ratings among independents (41% approve to 23% disapprove), and negative ratings among GOP voters (24% approve to 39% disapprove). “New Jersey voters are just getting to know Cory Booker as their Senator and generally giving him positive reviews,” said Patrick Murray, director of the Monmouth University Polling Institute. “They feel they have seen enough to say he deserves a full term.” A majority (55%) of Garden State voters say that Booker should be re-elected to the U.S. -

New Jersey Poll 33 September 1978 Hello, My Name Is (First and Last

New Jersey Poll 33 September 1978 Hello, my name is (first and last name). I'm (a student at/on the staff of) Rutgers University and I'm taking a (survey/public opinion poll) for the Eagleton Institute, I'd like your views on some important issues facing the state of New Jersey and the nation. 1. To begin with, for how many years have you lived in New Jersey, or have you lived here all your life? 1 LESS THAN ONE 2 1 OR 2 3 3-5 4 6-10 5 11 - 20 6 21 - 30 7 MORE THAN 30 8 ALL MY LIFE 9 DON'T KNOW 2. Overall, how good a job do you think the Governor of New Jersey--Brendan Byrne is doing--excellent, good, only fair, or poor? 1 EXCELLENT 2 GOOD 3 ONLY FAIR 4 POOR 9 DON'T KNOW 3. And how good a job do you think the New Jersey State Legislature is doing-- excellent, good, only fair, or poor? 1 EXCELLENT 2 GOOD 3 ONLY FAIR 4 POOR 9 DON'T KNOW Now let's turn to some questions on the job Jimmy Carter is doing as President-- For each question I ask you please tell me whether you think he is doing an excellent, good, only fair, or poor job? (REPEAT RESPONSE OPTIONS AS NEEDED ON REMAINING QUESTIONS.] 4. Overall, how would you rate the job Jimmy Carter is doing as President? 1 EXCELLENT 2 GOOD 3 ONLY FAIR 4 POOR 9 DON’T KNOW 5. Carter's handling of the problems of the economy? 1 EXCELLENT 2 GOOD 3 ONLY FAIR 2 4 POOR 9 DON’T KNOW 6. -

To See the Other 99 Members

the POWER LIST2014 POLITICKER_2014_Cover.indd 4 11/14/14 8:59:46 PM NEVER LOSING SIGHT OF THE ENDGAME FOCUSNewark New York Trenton Philadelphia Wilmington gibbonslaw.com Gibbons P.C. is headquartered at One Gateway Center, Newark, New Jersey 07102 T 973-596-4500 A_POLITICKER_2014_ads.indd 1 11/13/14 10:21:34 AM NORTHEAST CARPENTERS POLTICAL EDUCATION COMMITTEE DEDICATED TO SOCIAL JUSTICE FOR THE HARD WORKING MEN AND WOMEN OF NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK STATE AS TRADE UNIONISTS AND CITIZENS, WE ARE FOCUSED ON IMPROVING INDUSTRY STANDARDS AND EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES FOR UNION CARPENTERS AND THE SMALL AND LARGE BUSINESSES THAT EMPLOY THEM. OUR ADVOCACY IS CENTERED ON A SIMPLE AND ABIDING MOTTO: “WHEN CARPENTERS WORK, NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK WORK.” FICRST AN, RARITAN PAA II, SIT A18, ISON NJ 08837 732-417-9229 Paid for by the Northeast Regional Council of Carpenters Poltical Education Committee A_POLITICKER_2014_ads.indd 1 11/13/14 10:24:39 AM PolitickerNJ.com POWER LIST 2014 Editor’s Note elcome to PolitickerNJ’s 2014 Power List, another excursion into that raucous political universe tapped like a barrel at both ends, in the words of Ben Franklin, who would have likely shuddered at the invocation of his name in the Wcontext of this decidedly New Jersey enterprise. As always, the list does not include elected ofcials, judges or past governors. In keeping with past tradition, too, it promises to stir plenty of dismay, outrage, hurt feelings, and public tantrums at the annual League of Municipalities. We welcome it all in the spirit of more finely honing this conglomerate in progress and in the name, of course, of defending what we have wrought out of the political collisions of this most interesting year. -

Education Professional Experience

Epiphany Knedler 625 S Wheatland Ave, Apt 42 Sioux Falls, SD, 57106 (605) 670-2803 [email protected] www.epiphanyknedler.com EDUCATION 2017 ~ M.F.A. Photography 2020 East Carolina University Greenville, NC 2014 ~ B.F.A. Photography 2017 B.A. in Political Science University of South Dakota Vermillion, SD University Honors Thesis Scholar Magna Cum Laude 2013 ~ Undergraduate Studies in Political Science (transferred) 2014 Washington, DC The George Washington University PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2020 ~ Adjunct Instructor Present University of Southern Indiana, Evansville, IN Taught undergraduate courses in 2D Design – Color + Design. Students learn about the basics of visual communication and the elements and principles of art and design through projects using a variety of two-dimensional media. Students also explore the basics of color theory and ideas and concepts in art. Each project introduces contemporary and historic artists with emphasis on research. 2020 ~ Adjunct Instructor Present Forsyth Tech Community College, Winston-Salem, NC Taught undergraduate courses in Digital Design and Digital Photography. Students learn about digital art and photography using relevant software and project-based assignments. Students are prepared for future digital art experiences while learning about visual communication and creative problem solving through illustration, digital collage, and research. 2020 ~ Present Adjunct Instructor Pitt Community College, Greenville, NC Taught undergraduate courses in Introduction to Graphic Design and Digital Design. Students learn about digital art and graphic design through project-based assignments with a focus in digital tools and software including Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustrator, and Adobe InDesign. Students are prepared for future graphic design and digital art courses while learning about visual communication and creative problem solving through illustration, typography, digital collage, and research.