Decoding Chinese Strategic Intent in the Standoff at the Line of Actual Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Surface Energy Balance in a Cold-Arid Permafrost Environment

https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2019-286 Preprint. Discussion started: 9 March 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. The surface energy balance in a cold-arid permafrost environment, Ladakh Himalaya, India John Mohd Wani1, Renoj J. Thayyen2*, Chandra Shekhar Prasad Ojha1, and Stephan Gruber3 1Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Roorkee, India, 2Water Resources System Division, National Institute of Hydrology, Roorkee, India ([email protected]; [email protected]), 3Department of Geography & Environmental Studies, Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada Abstract: Cryosphere of the cold-arid trans-Himalayan region is unique with its significant permafrost cover. While the information on the permafrost characteristics and its extent started emerging, the governing energy regimes of this cryosphere region is of particular interest. This paper present the results of Surface Energy Balance (SEB) studies carried out in the upper 5 Ganglass catchment in the Ladakh region of India, which feed directly to the River Indus. The point SEB is estimated using the one-dimensional mode of GEOtop model from 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2017 at 4727 m a.s.l elevation. The model is evaluated using field monitored radiation components, snow depth variations and one-year near-surface ground temperatures and showed good agreement with the respective simulated values. The study site has an air 10 temperature range of – 23.7 to 18.1 °C with a mean annual average temperature (MAAT) of - 2.5 and ground surface temperature range of -9.8 to 19.1 °C. For the study period, the surface energy balance characteristics of the cold-arid site show that the net radiation was the major component with mean value of 28.9 W m-2, followed by sensible heat flux (13.5 W m-2) and latent heat flux (12.8 W m-2), and the ground heat flux was equal to 0.4 W m-2. -

Historical Places

Where to Next? Explore Jammu Kashmir And Ladakh By :- Vastav Sharma&Nikhil Padha (co-editors) Magazine Description Category : Travel Language: English Frequency: Twice in a Year Jammu Kashmir and Ladakh Unlimited is the perfect potrait of the most beautiful place of the world Jammu, Kashmir&Ladakh. It is for Travelers, Tourism Entrepreneurs, Proffessionals as well as those who dream to travel Jammu,Kashmir&Ladakh and have mid full of doubts. This is a new kind of travel publication which trying to promoting the J&K as well as Ladakh tourism industry and remove the fake potrait from the minds of people which made by media for Jammu,Kashmir&Ladakh. Jammu Kashmir and ladakh Unlimited is a masterpiece, Which is the hardwork of leading Travel writters, Travel Photographer and the team. This magazine has covered almost every tourist and pilgrimage sites of Jammu Kashmir & Ladakh ( their stories, history and facts.) Note:- This Magazine is only for knowledge based and fact based magazine which work as a tourist guide. For any kind of credits which we didn’t mentioned can claim for credits through the editors and we will provide credits with description of the relevent material in our next magazine and edit this one too if possible on our behalf. Reviews “Kashmir is a palce where not even words, even your emotions fail to describe its scenic beauty. (Name of Magazine) is a brilliant guide for travellers and explore to know more about the crown of India.” Moohammed Hatim Sadriwala(Poet, Storyteller, Youtuber) “A great magazine with a lot of information, facts and ideas to do at these beautiful places.” Izdihar Jamil(Bestselling Author Ted Speaker) “It is lovely and I wish you the very best for the initiative” Pritika Kumar(Advocate, Author) “Reading this magazine is a peace in itself. -

1962 Sino-Indian Conflict : Battle of Eastern Ladakh Agnivesh Kumar* Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India

OPEN ACCESS Freely available online Journal of Political Sciences & Public Affairs Editorial 1962 Sino-Indian Conflict : Battle of Eastern Ladakh Agnivesh kumar* Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India. E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL protests. Later they also constructed a road from Lanak La to Kongka Pass. In the north, they had built another road, west of the Aksai Sino-Indian conflict of 1962 in Eastern Ladakh was fought in the area Chin Highway, from the Northern border to Qizil Jilga, Sumdo, between Karakoram Pass in the North to Demchok in the South East. Samzungling and Kongka Pass. The area under territorial dispute at that time was only the Aksai Chin plateau in the north east corner of Ladakh through which the Chinese In the period between 1960 and October 1962, as tension increased had constructed Western Highway linking Xinjiang Province to Lhasa. on the border, the Chinese inducted fresh troops in occupied Ladakh. The Chinese aim of initially claiming territory right upto the line – Unconfirmed reports also spoke of the presence of some tanks in Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) – Track Junction and thereafter capturing it general area of Rudok. The Chinese during this period also improved in October 1962 War was to provide depth to the Western Highway. their road communications further and even the posts opposite DBO were connected by road. The Chinese also had ample animal In Galwan – Chang Chenmo Sector, the Chinese claim line was transport based on local yaks and mules for maintenance. The horses cleverly drawn to include passes and crest line so that they have were primarily for reconnaissance parties. -

Climate Vulnerability in Asia's High Mountains

Climate Vulnerability in Asia’s High Mountains COVER: VILLAGE OF GANDRUNG NESTLED IN THE HIMALAYAS. ANNAPURNA AREA, NEPAL; © GALEN ROWELL/MOUNTAIN LIGHT / WWF-US Climate Vulnerability in Asia’s High Mountains May 2014 PREPARED BY TAYLOR SMITH Independent Consultant [email protected] This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of WWF and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. THE UKOK PLATEAU NATURAL PARK, REPUBLIC OF ALTAI; © BOGOMOLOV DENIS / WWF-RUSSIA CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................1 4.2.1 Ecosystem Restoration ........................................... 40 4.2.2 Community Water Management .............................. 41 State of Knowledge on Climate Change Impacts .................. 1 4.3 Responding to Flooding and Landslides ....................... 41 State of Knowledge on Human Vulnerability ......................... 1 4.3.1 Flash Flooding ......................................................... 41 Knowledge Gaps and Policy Perspective .............................. 3 4.3.2 Glacial Lake Outburst Floods .................................. 42 Recommendations for Future Adaptation Efforts ................. 3 4.3.3 Landslides ............................................................... 43 4.4 Adaptation by Mountain Range ....................................... 44 Section I 4.4.1 The Hindu Kush–Karakorum–Himalaya Region -

China's Influence on Conflict Dynamics in South Asia

USIP SENIOR STUDY GROUP FINAL REPORT China’s Influence on Conflict Dynamics in South Asia DECEMBER 2020 | NO. 4 USIP Senior Study Group Report This report is the fourth in USIP’s Senior Study Group (SSG) series on China’s influence on conflicts around the world. It examines how Beijing’s growing presence is affecting political, economic, and security trends in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region. The bipartisan group was comprised of senior experts, former policymakers, and retired diplomats. They met six times by videoconference over the course of 2020 to examine how an array of issues—from military affairs to border disputes, trade and development, and cultural issues—come together to shape and be shaped by Chinese involvement. The group members drew from their deep individual experiences working in and advising the US government to generate a set of top-level findings and actionable policy recommen- dations. Unless otherwise sourced, all observations and conclusions are those of the SSG members. Cover illustration by Alex Zaitsev/Shutterstock The views expressed in this report are those of the members of the Senior Study Group alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2020 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org First published December 2020. -

1000+ Question Series PDF -Jklatestinfo

JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q1) The kashmir Valley was originally a huge lake called ? a) Manesar b) Neelam c) Satisar d) Both ‘b’ & ‘c’ Q2) Kalhana , a famous historian wrote ? a) Nilmatpurana b) Rajtarangini c) Both d) None of these Q3) The First king mentioned by Kalhana is ? a) Gonanda I b) Durlabha Vardhana c) Ashoka d) Jalodbhava Q4) The outer plains doesn’t cover which of the following ? a) RS Pura b) Kathua c) Akhnoor d) Udhampur Q5) When J&K became Union Territory ? a) August 5, 2019 b) October 31, 2019 c) September 5, 2019 d) October 1 , 2019 JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q6) Which among the following is the welcome dance for spring season ? a) Bhand Pathar b) Dhumal c) Kud d) Rouf Q7) Total number of districts in J&K ? a) 22 b) 21 c) 20 d) 18 Q8) On which hill the Vaishno Devi Mandir is located ? a) Katra b) Trikuta c) Udhampur d) Aru Q9) The SI unit of charge is ? a) Ampere b) Coulomb c) Kelvin d) Watt Q10) The filament of light bulb is made up of ? a) Platinum b) Antimony c) Tungsten d) Tantalum JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q11) Battle of Plassey was fought in ? a) 1757 b) 1857 c) 1657 d) 1800 Q12) Indian National Congress was formed by ? a) WC Bannerji b) George Yuli c) Dada Bhai Naroji d) A.O HUme Q13) The Tropic of cancer doesn’t pass through ? a) MP b) Odisha c) West Bengal d) Rajasthan Q14) Which of the following is Trans-Himalyan River ? a) Ganga b) Ravi c) Yamuna d) Indus Q15) Rovers cup is related to ? a) Hockey b) Cricket c) Football d) Cricket JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ -

`15,999/-(Per Person)

BikingLEH Adventure 06 DAYS OF THRILL STARTS AT `15,999/-(PER PERSON) Leh - Khardungla Pass - Nubra Valley - Turtuk - Pangong Tso - Tangste [email protected] +91 9974220111 +91 7283860777 1 ABOUT THE PLACES Leh, a high-desert city in the Himalayas, is the capital of the Leh region in northern India’s Jammu and Kashmir state. Originally a stop for trading caravans, Leh is now known for its Buddhist sites and nearby trekking areas. Massive 17th-century Leh Palace, modeled on the Dalai Lama’s former home (Tibet’s Potala Palace), overlooks the old town’s bazaar and mazelike lanes. Khardung La is a mountain pass in the Leh district of the Indian union territory of Ladakh. The local pronunciation is "Khardong La" or "Khardzong La" but, as with most names in Ladakh, the romanised spelling varies. The pass on the Ladakh Range is north of Leh and is the gateway to the Shyok and Nubra valleys. Nubra is a subdivision and a tehsil in Ladakh, part of Indian-administered Kashmir. Its inhabited areas form a tri-armed valley cut by the Nubra and Shyok rivers. Its Tibetan name Ldumra means "the valley of flowers". Diskit, the headquarters of Nubra, is about 150 km north from Leh, the capital of Ladakh. Turtuk is one of the northernmost villages in India and is situated in the Leh district of Ladakh in the Nubra Tehsil. It is 205 km from Leh, the district headquarters, and is on the banks of the Shyok River. Pangong Tso or Pangong Lake is an endorheic lake in the Himalayas situated at a height of about 4,350 m. -

Ladakh's Increasing Vulnerability to Flash Floods and Debris Flows

HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES Hydrol. Process. 30, 4214–4223 (2016) Published online 21 June 2016 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/hyp.10919 A clear and present danger: Ladakh’s increasing vulnerability to flash floods and debris flows Alan D. Ziegler,1* Abstract 2 Sebastian I. Cantarero, This preliminary investigation of the recent spate of deadly flash floods and debris Robert J. Wasson,3 flows in Ladakh (India) over the last decade identifies uncontrolled development in Pradeep Srivastava,4 hazardous locations as an important factor contributing to loss of life and property 5 damage in this high mountain desert. The sediments exposed in the channel banks Sonam Spalzin, and on the alluvial fans of several mountain streams in the area indicate a long Winston T. L. Chow1,3 and history of flash floods and debris flows resulting from intense storms, which appear Jamie Gillen1 to have increased in frequency within the last decade. The signposts of these recurrent hazards are being ignored as a growing economy, which is boosted by a 1 Geography Department, National well-established tourism industry, is now driving development onto lands that are University of Singapore, Singapore, susceptible to floods and debris flow hazards. In this science briefing we argue that 117568 the increasing vulnerability in Ladakh should be addressed with sound disaster 2 Tropical Marine Science Institute, National University of Singapore, governance strategies that are proactive, rather than reactionary. Copyright © Singapore 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 3 Institute of Water Policy, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National Key Words floods; vulnerability; debris flows; tourism; climate change University of Singapore, Singapore 4 Wadia Institute for Himalayan Geology, Dehra Dun, India Introduction 5 Archeological Survey of India, The nature of a flood disaster is shaped primarily by a combination of the Srinagar, India increasing exposure and impacts arising from the geophysical hazard itself (i.e. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

ERONET Pre Reqst Format.Xlsx

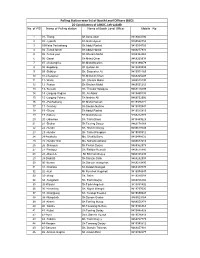

Polling Station wise list of Booth Level Officers (BLO) 26-Constituency of LAHDC, Leh-Ladakh No. of P/S Name of Polling station Name of Booth Level Officer Mobile . No 1 01- Thang Sh Sana Ullah 9419864100 2 02 -Tyakshi Sh Mohs Ayoub 9469552752 3 03Waha Pachathang Sh Abdul Rashid 9419534709 4 04 -Turtuk farool Sh Abdul Hamid 9469277933 5 05 -Turtuk youl Sh Ghulam Mohd 9469462863 6 06 -Garari Sh Mohd Omar 9469265938 7 07 -Chulungkha Sh Mohd Ibrahim 9419388079 8 08 -Bogdang Sh Qurban Ali 9419829393 9 09 -Skilkhor Sh. Shamsher Ali 9419971169 10 10-Changmar Sh Mohd Ali Khan 9469265209 11 11- Waris Sh. Ghulam Mohd 9469515130 12 12 -Fastan Sh Ghulam Mohd 9469531252 13 13- Sunudo Sh. Thoskor Spalgyas 9469176699 14 14 -Largyap Gogma Sh. Ali Akbar 9419440193 15 15 -Largyap Yokma Sh Ibrahim Ali 9469732596 16 16 –Pachathang Sh Mohd Hassan 9419386471 17 17 -Terchay Sh Sonam Nurboo 9419880947 18 18 –Skuru Sh Abdul Rashid 9419515915 19 19 -Rakuru Sh Mohd Mussa 9469212778 20 20 -Udmaroo Sh. Tashi Dawa 9419440625 21 21 -Shukur Sh Tsering Dorjey 9469178364 22 22 -Hundri Sh. Stanzin Dorjay 9469617039 23 23 -Hunder Sh Tashi Wangdus 9419550812 24 24-Awaksha Ms. Shakila Bano 9419448032 25 25 -Hunder Dok Ms. Naheda Akhatar 9469572613 26 26 -Skampuk Sh Tsetan Dorjey 9469362975 27 27 -Partapur Sh. Rehbar Hussain 9469571886 28 28 –Diskit-A Sh Rinchen Dorjey 9469165230 29 29-Diskit-B Sh Stanzin Galik 9469292903 30 30 -Burma Sh Stanzin Wangchok 9469213895 31 31 -Charasa Sh Deldan Namgail 9469387070 32 32 –Kuri Mr Punchok Angchok 9419974947 33 33- Murgi Sh. -

Chushul Travel Guide - Page 1

Chushul Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/chushul page 1 Max: Min: 8.0°C Rain: 21.79999923 22.7999992370605 When To 7060547°C 47mm Chushul Aug Chushul is a valley in Ladakh, in the Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. VISIT Max: Min: Rain: state of Jammu and Kashmir in 20.29999923 7.300000190 21.7000007629394 India. 7060547°C 734863°C 53mm http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-chushul-lp-1186507 Sep Very cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Famous For : Places To VisitCity Jan Max: Min: Rain: 6.5mm Freezing weather. Carry Heavy woollen. 16.29999923 2.200000047 7060547°C 683716°C Max: -4.0°C Min: - Rain: It was an airstrip used in the Sino-Indian 19.89999961 2.29999995231628 8530273°C 4mm Oct War. It is close to Rezang La and Panggong Freezing weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Lake at a height of 4360 metres. The Feb Max: Min: - Rain: Chushul village was the block headwaters of Freezing weather. Carry Heavy woollen. 8.300000190 7.800000190 2.70000004768371 734863°C 734863°C 6mm Chanthhang block of Ladakh district prior to Max: -2.0°C Min: - Rain: 17.10000038 1.60000002384185 the 1962 war with china. 1469727°C 8mm Nov Freezing weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Mar Max: Min: -14.0°C Rain: Freezing weather. Carry Heavy woollen. 3.099999904 0.60000002384185 6325684°C 79mm Max: Min: - Rain: 2.299999952 13.10000038 1.70000004768371 316284°C 1469727°C 58mm Dec Freezing weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Apr Max: - Min: - Rain: Freezing weather. Carry Heavy woollen. 1.200000047 18.10000038 1.29999995231628 6837158°C 1469727°C 42mm Max: Min: -8.0°C Rain: 7.400000095 2.20000004768371 367432°C 6mm May What To Very cold weather. -

TA 7417- IND: Support for the National Action Plan on Climate Change

TA7417-IND Support for the National Action Plan for Climate Change Support to the National Water Mission TA 7417 - IND: Support for the National Action Plan on Climate Change Support to the National Water Mission Final Report September 2011 Appendix 1 India Water Systems PREPARED FOR Government of India Governments of Punjab, Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu Asian Development Bank Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC ii Appendix 1 India Water Systems Appendix 1 India Water Systems Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC ii Appendix 1 India Water Systems Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC iii Appendix 1 India Water Systems SUMMARY OF ABBREVIATIONS A1B IPCC Climate Change Scenario A1 assumes a world of very rapid economic growth, a global population that peaks in mid-century and rapid introduction of new and more efficient technologies. A1 is divided into three groups that describe alternative directions of technological change: fossil intensive (A1FI), non-fossil energy resources (A1T) and a balance across all sources (A1B). A2 IPCC climate change Scenario A2 describes a very heterogeneous world with high population growth, slow economic development and slow technological change. ADB Asian Development Bank AGTC Agriculture Technocrats Action Committee of Punjab AOGCM Atmosphere Ocean Global Circulation Model APHRODITE Asian Precipitation - Highly-Resolved Observational Data Integration Towards Evaluation of Water Resources - a observed gridded rainfall dataset developed in Japan APN Asian Pacific Network for Global Change Research AR Artificial Recharge AR4 IPCC Fourth Assessment Report AR5 IPCC Fifth Assessment Report AWM Adaptive Water Management B1 IPCC climate change Scenario B1 describes a convergent world, with the same global population as A1, but with more rapid changes in economic structures toward a service and information economy.