Observing the 2011 Referendum on the Self-Determination of Southern Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RVI Electoral Designs.Pdf

Electoral Designs Proportionality, representation, and constituency boundaries in Sudan’s 2010 elections Marc Gustafson Electoral Designs | 1 Electoral Designs Proportionality, representation, and constituency boundaries in Sudan’s 2010 elections Marc Gustafson Date 2010 Publisher Rift Valley Institute Editor Emily Walmsley Designer Scend www.scend.co.uk Cover image Jin-ho Chung ISBN 978-1-907431-01-2 Rights Published under Creative Commons license Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Contents List of tables and figures 4 About the Rift Valley Institute 5 About the author 5 Acknowledgements 6 Acronyms 6 Summary 7 I. Introduction 8 II. Electoral design in other post-conflict African countries 10 III. Sudan’s mixed electoral system 13 IV. Creating electoral constituencies 16 V. Conclusion 42 Appendix 46 Bibliography 64 List of tables and figures Tables Table 1 Electoral systems of African states 11 Table 2 Sudan’s elections and corresponding electoral systems 15 Table 3 Formulas for calculating the number of National Assembly constituencies for each state 19 Table 4 Distribution of constituencies and National Assembly seats 20 Table 5 Party and women’s list seats 22 Figures Figure 1 Allocation of National Legislative Assembly seats 15 Figure 2 Regional distribution of seats 24 Figure 3 Hand-marked corrections of population figures on the boundary reports for Kassala, Blue Nile, and Lakes States 29 Figure 4 Geographical constituencies of North Darfur 33 Figure 5 Description of constituency 32 (south Dabib and north Abyei) 35 4 | Electoral Designs About the Rift Valley Institute The Rift Valley Institute is a non-profit research, education and advocacy organization operating in Sudan, the Horn of Africa, East Africa, and the Great Lakes. -

Map of South Sudan

UNITED NATIONS SOUTH SUDAN Geospatial 25°E 30°E 35°E Nyala Ed Renk Damazin Al-Fula Ed Da'ein Kadugli SUDAN Umm Barbit Kaka Paloich Ba 10°N h Junguls r Kodok Āsosa 10°N a Radom l-A Riangnom UPPER NILEBoing rab Abyei Fagwir Malakal Mayom Bentiu Abwong ^! War-Awar Daga Post Malek Kan S Wang ob Wun Rog Fangak at o Gossinga NORTHERN Aweil Kai Kigille Gogrial Nasser Raga BAHR-EL-GHAZAL WARRAP Gumbiel f a r a Waat Leer Z Kuacjok Akop Fathai z e Gambēla Adok r Madeir h UNITY a B Duk Fadiat Deim Zubeir Bisellia Bir Di Akobo WESTERN Wau ETHIOPIA Tonj Atum W JONGLEI BAHR-EL-GHAZAL Wakela h i te LAKES N Kongor CENTRAL Rafili ile Peper Bo River Post Jonglei Pibor Akelo Rumbek mo Akot Yirol Ukwaa O AFRICAN P i Lol b o Bor r Towot REPUBLIC Khogali Pap Boli Malek Mvolo Lowelli Jerbar ^! National capital Obo Tambura Amadi WESTERN Terakeka Administrative capital Li Yubu Lanya EASTERN Town, village EQUATORIAMadreggi o Airport Ezo EQUATORIA 5°N Maridi International boundary ^! Juba Lafon Kapoeta 5°N Undetermined boundary Yambio CENTRAL State (wilayah) boundary EQUATORIA Torit Abyei region Nagishot DEMOCRATIC Roue L. Turkana Main road (L. Rudolf) Railway REPUBLIC OF THE Kajo Yei Opari Lofusa 0 100 200km Keji KENYA o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 50 100mi CONGO o e The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

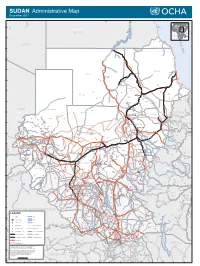

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011 Faris IQLIT Ezbet Dush Ezbet Maks el-Qibli Ibrim DARAW KOM OMBO Al Hawwari Al-Kufrah Nagel-Gulab ASWAN At Tallab 24°N EGYPT 23°N R E LIBYA Halaib D S 22°N SUDAN ADMINISTRATED BY EGYPT Wadi Halfa E A b 'i Di d a i d a W 21°N 20°N Kho r A bu Sun t ut a RED SEA a b r A r o Porth Sudan NORTH Abu Hamad K Dongola Suakin ur Qirwid m i A ad 19°N W Bauda Karima Rauai Taris Tok ar e il Ehna N r e iv R RIVER NILE Ri ver Nile Desert De Bayouda Barbar Odwan 18°N Ed Debba K El Baraq Mib h o r Adara Wa B a r d a i Hashmet Atbara ka E Karora l Atateb Zalat Al Ma' M Idd Rakhami u Abu Tabari g a Balak d a Mahmimet m Ed Damer Barqa Gereis Mebaa Qawz Dar Al Humr Togar El Hosh Al Mahmia Alghiena Qalat Garatit Hishkib Afchewa Seilit Hasta Maya Diferaya Agra 17°N Anker alik M El Ishab El Hosh di El Madkurab Wa Mariet Umm Hishan Qalat Kwolala Shendi Nakfa a r a b t Maket A r a W w a o d H i i A d w a a Abdullah Islandti W b Kirteit m Afabet a NORTH DARFUR d CHAD a Zalat Wad Tandub ug M l E i W 16°N d Halhal Jimal Wad Bilal a a d W i A l H Aroma ERITREA Keren KHARTOUM a w a KASSALA d KHARTOUM Hagaz G Sebderat Bahia a Akordat s h Shegeg Karo Kassala Furawiya Wakhaim Surgi Bamina New Halfa Muzbat El Masid a m a g Barentu Kornoi u Malha Haikota F di Teseney Tina Um Baru El Mieiliq 15°N Wa Khashm El Girba Abu Quta Abu Ushar Tandubayah Miski Meheiriba EL GEZIRA Sigiba Rufa'ah Anka El Hasahisa Girgira NORTH KORDOFAN Ana Bagi Baashim/tina Dankud Lukka Kaidaba Falankei Abdel Shakur Um Sidir Wad Medani Sodiri Shuwak Badime Kulbus -

PRESS RELEASE Marina Modi Public &Media Relations Officer [email protected] 0955950026 #Defyhatenow: Mobilizing Civic A

PRESS RELEASE Marina Modi Public &Media relations Officer [email protected] 0955950026 #defyhatenow: Mobilizing Civic Action against Hate Speech and Directed Social Media Incitement to Violence in South Sudan. Juba, 03 November 2017 #DEFYHATENOW WIKIPEDIA WORKSHOP #defyhatenow initiative will be training students from the University of Juba on writing and feeding /editing information about South Sudan on Wikipedia,the online global encyclopedia from 6- 9 November 2017. Objectives; 1. Empowering South Sudanese to have a global voice in national narratives and knowledge in the quest for lasting peace. 2. Generating more knowledge about other people-to-people peace-building issues. 3. Initiate a sustainable movement of South Sudanese Wikipedia writers/editors. Why Wikipedia? South Sudan is underrepresented at Wikipedia, the world's largest online encyclopedia. There are hardly 1.500 articles about South Sudanese subjects and most of them are just stubs, since even entries about many major towns and states only feature a couple of lines. While Wikipedia is one of the most used and visited websites, next to no content about South Sudan has been generated inside the country itself. Instead, most information about South Sudan has been created by outsiders. With regard to internal peace-making, #defyhatenow will be working with the student run #kefkum initiative to collaboratively edit, starting with a critical review of Wunlit conference and then create a comprehensive article on Wikipedia. As a pilot example, #defyhatenow has already edited the Wikipedia article about Deim Zubeir from a one-line stub to a multi-facetted overview. Deim Zubeir has recently been included on South Sudan's first tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage sites. -

Observing Sudan's 2010 National Elections

Observing Sudan’s 2010 National Elections April 11–18, 2010 Final Report Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. Observing Sudan’s 2010 National Elections April 11–18, 2010 Final Report One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword . .1 Postelection Developments ..................47 Executive Summary .........................3 Counting . 47 Historical and Political Tabulation . 49 Background of Sudan . .8 Election Results . .50 Census . .10 Electoral Dispute Resolution . 51 Political Context of the April Election . 10 Darfur and Other Special Topics .............54 Overview of the Carter Darfur . .54 Center Observation Mission .................13 Enfranchising the Displaced . 55 Legal Framework of the Sudan Elections.......15 Political Developments Following the Election . 56 Electoral System . 17 Census in South Kordofan Participation of Women, Minorities, and Southern Sudan . .57 and Marginalized Groups. 17 Pastoralists and the Election . 57 Election Management . 18 Bashir’s Threats . 57 Boundary Delimitation . .20 Conclusions and Recommendations ...........59 Voter Registration and the General Election Recommendations . 59 Pre-election Period . 24 Southern Sudan Referendum Voter Registration . .24 Recommendations . .70 Voter Education . 30 Abyei Referendum Candidates, Parties, and Campaigns . .31 Recommendations . .80 The Media . 35 Appendix A: Acknowledgments . .81 Civil Society . .36 Appendix B: List of Delegation and Staff ......83 Electoral Dispute Resolution. 37 Appendix C: Terms and Abbreviations ........86 Election-Related Violence. 39 Appendix D: The Carter Center in Sudan .....87 The Election Period . .40 Appendix E: Carter Center Statements Poll Opening . .40 on the Sudan Elections .....................89 Polling. 42 Appendix F: Carter Center Observer Poll Closing. 45 Deployment Plan .........................169 Appendix G: Registration and Election Day Checklists ...........................170 Appendix H: Letter of Invitation . -

South Sudan - Crisis Fact Sheet #4, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2019 March 8, 2019

SOUTH SUDAN - CRISIS FACT SHEET #4, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2019 MARCH 8, 2019 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2018 Insecurity in Yei results in unknown number of civilian deaths, prevents 15,000 5% 7% 20% people from receiving aid 7.1 million 7% Estimated People in South Health actors continue EVD awareness Sudan Requiring Humanitarian 10% and screening activities Assistance 19% 2019 Humanitarian Response Plan – WFP conducts first road delivery to 15% December 2018 central Unity 17% Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (20%) Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (19%) HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Health (17%) 6.5 million FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE Nutrition (15%) Estimated People in Need of Protection (10%) Food Assistance in South Sudan Agriculture & Food Security (7%) USAID/OFDA $135,187,409 IPC Technical Working Group – Humanitarian Coordination & Info Management (7%) February 2019 Shelter & Settlements (5%) USAID/FFP $398,226,647 3 State/PRM $91,553,826 1.9 million USAID/FFP2 FUNDING $624,967,8824 Estimated IDPs in BY MODALITY IN FY 2018 1% TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE South Sudan SOUTH SUDAN CRISIS IN FY 2018 UN – January 31, 2019 84% 9% 5% U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (84%) 1% $3,756,094,855 Local & Regional Food Procurement (9%) TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE Complementary Services (5%) SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE IN FY 2014–2018, Cash Transfers for Food (1%) INCLUDING FUNDING FOR SOUTH SUDANESE 191,238 Food Vouchers (1%) REFUGEES IN NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES Estimated Individuals Seeking Refuge at UNMISS Bases UNMISS – March 4, 2019 KEY DEVELOPMENTS Ongoing violence between Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GoRSS) and opposition forces near Central Equatoria State’s Yei area has displaced an estimated 2.3 million 7,400 people to Yei town since December and is preventing relief agencies from reaching Estimated Refugees and Asylum more than 15,000 additional people seeking safety outside of Yei, the UN reports. -

Decisions and Deadlines a Critical Year for Sudan

Decisions and Deadlines A Critical Year for Sudan A Chatham House Report Edward Thomas Decisions and Deadlines A Critical Year for Sudan A Chatham House Report Edward Thomas i www.chathamhouse.org.uk Chatham House has been the home of the Royal Institute of International Affairs for nearly ninety years. Our mission is to be a world-leading source of independent analysis, informed debate and influential ideas on how to build a prosperous and secure world for all. © Royal Institute of International Affairs, January 2010 Chatham House (the Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinion of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. The PDF file of this report on the Chatham House website is the only authorized version of the PDF and may not be published on other websites without express permission. A link to download the report from the Chatham House website for personal use only should be used where appropriate. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. The Royal Institute of International Affairs Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London, SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: +44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org.uk Charity Registration No. 208223 ISBN 978-1-86203-229-3 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. -

Utd^L. Dean of the Graduate School Ev .•^C>V

THE FASHODA CRISIS: A SURVEY OF ANGLO-FRENCH IMPERIAL POLICY ON THE UPPER NILE QUESTION, 1882-1899 APPROVED: Graduate ttee: Majdr Prbfessor ~y /• Minor Professor lttee Member Committee Member irman of the Department/6f History J (7-ZZyUtd^L. Dean of the Graduate School eV .•^C>v Goode, James Hubbard, The Fashoda Crisis: A Survey of Anglo-French Imperial Policy on the Upper Nile Question, 1882-1899. Doctor of Philosophy (History), December, 1971, 235 pp., bibliography, 161 titles. Early and recent interpretations of imperialism and long-range expansionist policies of Britain and France during the period of so-called "new imperialism" after 1870 are examined as factors in the causes of the Fashoda Crisis of 1898-1899. British, French, and German diplomatic docu- ments, memoirs, eye-witness accounts, journals, letters, newspaper and journal articles, and secondary works form the basis of the study. Anglo-French rivalry for overseas territories is traced from the Age of Discovery to the British occupation of Egypt in 1882, the event which, more than any other, triggered the opening up of Africa by Europeans. The British intention to build a railroad and an empire from Cairo to Capetown and the French dream of drawing a line of authority from the mouth of the Congo River to Djibouti, on the Red Sea, for Tied a huge cross of European imperialism over the African continent, The point of intersection was the mud-hut village of Fashoda on the left bank of the White Nile south of Khartoum. The. Fashoda meeting, on September 19, 1898, of Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand, representing France, and General Sir Herbert Kitchener, representing Britain and Egypt, touched off an international crisis, almost resulting in global war. -

Shifting Terrains of Political Participation in Sudan

Shifting Terrains of Political Participation in Sudan Elements dating from the second colonial (1898–1956) period to the contemporary era Shifting Terrains of Political Participation in Sudan Elements dating from the second colonial (1898–1956) period to the contemporary era Azza Ahmed Abdel Aziz and Aroob Alfaki In collaboration with: © 2021 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. References to the names of countries and regions in this publication do not represent the official position of International IDEA with regard to the legal status or policy of the entities mentioned. [CCL image] The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/> International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <http://www.idea.int> This report was prepared in the context of a programme entitled “Supporting Sudan’s Democratic Transition’. The programme includes a series of components all of which aim to support Sudan’s transition to a democratic system of government, and to contribute to SDG 16 to promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels. -

Sudan Final Report

SUDAN FINAL REPORT Southern Sudan Referendum 9‐15 January 2011 EUROPEAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION This report was produced by the European Union Election Observation Mission to the Southern Sudan Referendum and presents the mission’s findings on the Referendum held from 9–15 January 2011. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the European External Action Service or the European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the European External Action Service or the European Commission. The European External Action Service does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. European Union Election Observation Mission Page 3 of 107 Final Report on the Southern Sudan Referendum, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENT I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 II. INTRODUCTION 10 III. POLITICAL BACKGROUND 11 POLITICAL CONTEXT 11 POST‐REFERENDUM CONTEXT 13 IV. LEGAL FRAMEWORK 14 SUDAN’S INTERNATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMITMENTS 14 NATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK 14 ELIGIBILITY 16 V. COMPLAINTS AND APPEALS 17 COMPLAINTS TO THE SSRC 17 APPLICATIONS TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT 17 VI. REFERENDUM ADMINISTRATION 19 STRUCTURE AND COMPOSITION OF THE REFERENDUM ADMINISTRATION BODIES 19 NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL PARTNER SUPPORT TO THE REFERENDUM PROCESS 20 THE GOSS TASK FORCE ON THE REFERENDUM 22 PERFORMANCE OF THE REFERENDUM ADMINISTRATION 23 VII. VOTER REGISTRATION 25 VOTER REGISTRATION PROCEDURES 26 APPEALS AND OBJECTIONS AT VOTER REGISTRATION 29 ASSESSMENT OF VOTER REGISTRATION PROCESS 31 VIII. PARTICIPATION OF CIVIL SOCIETY 32 VOTER EDUCATION AND INFORMATION AND CIVIL SOCIETY 32 DOMESTIC ELECTION OBSERVATION 33 INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION 34 IX. -

Everyone and Everything Is a Target

THE IMPACT ON CHILDREN OF ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE AND DENIAL OF HUMANITARIAN ACCESS IN SOUTH SUDAN “Everyone and Everything Is a Target” About Watchlist Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict (“Watchlist”) strives to end violations against children in armed conflicts and to guarantee their rights. As a global network, Watchlist builds partnerships among local, national, and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), enhancing mutual capacities and strengths. Working together, we collect and disseminate information on violations against children in conflicts in order to influence key decision-makers and implement programs and policies that effectively protect children. For further information about Watchlist, please contact: [email protected] or visit: www.watchlist.org This report was researched and written by Christine Monaghan, PhD, with support from Bonnie Berry, Adrianne Lapar, and Cara Antonaccio. Vesna Jaksic Lowe copyedited the report. Watchlist would also like to thank the many domestic and international NGOs, UN agencies, and individuals who participated in the research, generously shared their stories and experiences, and provided feedback on the report. “Everyone and Everything Is a Target” THE IMPACT ON CHILDREN OF ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE AND DENIAL OF HUMANITARIAN ACCESS IN SOUTH SUDAN Table of Contents Map of South Sudan 2 Acronyms 3 Executive Summary and Recommendations 4 Methodology 10 Conflict Context 11 Pre-2016 Health Context 13 Health Context during the Reporting Period 14 Compounding Health Challenges due to Attacks and Denial of Humanitarian Access 16 Focus Regions 20 a. Greater Upper Nile 20 b. Bahr el Ghazal 25 c. Equatoria 27 Conclusion 32 Endnotes 33 D 24° 26° 28° 30° 32 34 in 36° ° ° de En Nahud r 12° Abu Zabad SOUTH 12° SOUTH SUDAN Ed Damazin SUDAN SUDAN Al Fula Renk Ed Da'ein Tullus Nuba Mts. -

E4220v2 Republic of South Sudan Ministry of Agriculture & Forestry

E4220v2 Republic of South Sudan Ministry of Agriculture & Forestry Public Disclosure Authorized EMERGENCY FOOD CRISIS RESPONSE PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT REPORT May 2013 Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 1. BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROJECT AND THE STUDY 5 2. AN OVERVIEW OF THE AGRICULTURE SECTOR IN SOUTH SUDAN 14 3. REVIEW OF THE RELEVANT POLICIES, LAWS AND REGULATIONS 19 4. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT ACTIVITIES AND IMPLEMENTATION APPROACH 26 6. PUBLIC CONSULTATIONS AND DISCLOSURE 48 7. PEST MANAGEMENT 52 8. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ISSUES, IMPACTS AND MITIGATION 55 9. ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING PLAN 60 10. SUMMARY OF THE STUDY 66 11. REFERENCES 69 ii LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AAHI Action Africa Help International CES Central Equatoria State CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement EA Environmental Assessment EFCRP Emergency Food Crisis and Response Project ESA Environmental and Social Assessment ESAF Environment and Social Assessment Framework ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMF Environment and Social Management Framework ESMP Environment and Social Management Plan FAO Food and Agriculture Organization GDP Gross Domestic Product GFRP Global Food Crisis Response Program GNI Gross National Income GoSS Government of Southern Sudan IPM Integrated Pest Management IPMF Integrated Pest Management Framework IPMP Integrated Peoples Management