Snakebites in the Global Health Agenda of the Twenty First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snake Bite Protocol

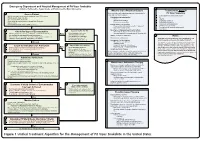

Lavonas et al. BMC Emergency Medicine 2011, 11:2 Page 4 of 15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-227X/11/2 and other Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center treatment of patients bitten by coral snakes (family Ela- staff. The antivenom manufacturer provided funding pidae), nor by snakes that are not indigenous to the US. support. Sponsor representatives were not present dur- At the time this algorithm was developed, the only ing the webinar or panel discussions. Sponsor represen- antivenom commercially available for the treatment of tatives reviewed the final manuscript before publication pit viper envenomation in the US is Crotalidae Polyva- ® for the sole purpose of identifying proprietary informa- lent Immune Fab (ovine) (CroFab , Protherics, Nash- tion. No modifications of the manuscript were requested ville, TN). All treatment recommendations and dosing by the manufacturer. apply to this antivenom. This algorithm does not con- sider treatment with whole IgG antivenom (Antivenin Results (Crotalidae) Polyvalent, equine origin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Final unified treatment algorithm Marietta, Pennsylvania, USA)), because production of The unified treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1. that antivenom has been discontinued and all extant The final version was endorsed unanimously. Specific lots have expired. This antivenom also does not consider considerations endorsed by the panelists are as follows: treatment with other antivenom products under devel- opment. Because the panel members are all hospital- Role of the unified treatment algorithm -

Valneva to Partner with Instituto Butantan on Single-Shot Chikungunya Vaccine for Low- and Middle- Income Countries

VALNEVA SE Campus Bio-Ouest | 6, Rue Alain Bombard 44800 Saint-Herblain, France Valneva to Partner with Instituto Butantan on Single-Shot Chikungunya Vaccine for Low- and Middle- Income Countries Saint-Herblain (France), Sao Paulo, (Brazil), May 5, 2020 – Valneva SE (“Valneva” or “the Company”), a specialty vaccine company, and Instituto Butantan, producer of immunobiologic products, today announced the signing of a binding term sheet for the development, manufacturing and marketing of Valneva’s single-shot chikungunya vaccine, VLA1553, in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs). The collaboration falls within the framework of the $23.4 million in funding Valneva received from the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) in July 20191. The definitive agreements are expected to be finalized in the next six months. After the signing of the definitive agreements, Valneva will transfer its chikungunya vaccine technology to Instituto Butantan, who will develop, manufacture and commercialize the vaccine in LMICs. In addition, Instituto Butantan will provide certain clinical and Phase 4 observational studies that Valneva will use to meet regulatory requirements. The agreement will include small upfront and technology transfer milestones. Valneva held its End of Phase 2 meeting with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2020 and is now preparing to initiate Phase 3 clinical studies in the U.S. later this year. Thomas Lingelbach, Chief Executive Officer of Valneva, commented, “Although millions of people have been affected by chikungunya, there is currently no vaccine and no effective treatment available against this debilitating disease. We look forward to working with Instituto Butantan to help address this current public health crisis and speed up the development of a chikungunya vaccine in LMICs, which are high outbreak areas." Dr. -

Medeiros Et Al., 2008.Pdf

Toxicon 52 (2008) 606–610 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Toxicon journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/toxicon Epidemiologic and clinical survey of victims of centipede stings admitted to Hospital Vital Brazil (Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil) C.R. Medeiros a,e, T.T. Susaki a, I. Knysak b, J.L.C. Cardoso a, C.M.S. Ma´laque a, H.W. Fan a, M.L. Santoro c, F.O.S. França a, K.C. Barbaro d,* a Hospital Vital Brazil, Butantan Institute, Av. Vital Brasil 1500, 05503-900, Sa˜o Paulo, SP, Brazil b Laboratory of Arthropods, Butantan Institute, Av. Vital Brasil 1500, 05503-900, Sa˜o Paulo, SP, Brazil c Laboratory of Pathophysiology, Butantan Institute, Av. Vital Brasil 1500, 05503-900, Sa˜o Paulo, SP, Brazil d Laboratory of Immunopathology, Butantan Institute, Av. Vital Brasil 1500, 05503-900, Sa˜o Paulo, SP, Brazil e Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, University of Sa˜o Paulo School of Medicine Hospital das Clı´nicas, Brazil article info abstract Article history: We retrospectively analyzed 98 proven cases of centipede stings admitted to Hospital Vital Received 16 January 2008 Brazil, Butantan Institute, Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil, between 1990 and 2007. Most stings occurred Received in revised form 27 June 2008 at the metropolitan area of Sa˜o Paulo city (n ¼ 94, 95.9%), in the domiciles of patients Accepted 16 July 2008 (n ¼ 67, 68.4%), and during the warm-rainy season (n ¼ 60, 61.2%). The mean age of the Available online 29 July 2008 victims was 32.0 Æ 18.8-years-old. -

Stiiemtific PNSTHTUTHQNS in LATIN AMERICA the BUTANTAN Institutel

StiIEMTIFIC PNSTHTUTHQNS IN LATIN AMERICA THE BUTANTAN INSTITUTEl Director: Dr. Jayme Cavalcanti Xão Paulo, Brazil The ‘%utantan Institute of Serum-Therapy,” situated in the middle of a large park on the outskirts of Sao Paulo, was founded in 1899 by the Government of the State primarily for the purpose of preparing plague vaccine and serum. Dr. Vital Brazil, the first Director of the Institute, resumed there the studies on snake poisons which he had begun in 1895 on his return from France, and his work and that of his colleagues soon caused the Institute to become world-famous for its work in that field. Dr. Brazil was one of the first workers to observe the specificity of snake venom, that is, that different species of snakes have different venoms and that, therefore, different sera must be made for treating their bites. His work on snake poisons included zoological studies of the various species of snakes in the country, with their geographic distribution, biology, common names, types of venom, etc.; the prepara- tion of sera from various types of venom; the teaching of preventive measures, including the method of capturing snakes and sending them ’ to the specialized centers; establishment of a system of exchange of live snakes for ampules of serum between the farmers and the Insti- tute; the introduction into the death certificate of an entry for the recording of snake-bite as a cause of death, and the compiling of sta- tistics of bites, treatment used, and results. Dr. Brazil was followed in the directioqof the Institute, in 1919, by Dr. -

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

Vital Brazil E a Autonomia (Vital) Para a Educação Introdução Imagine Se

Vital Brazil e a autonomia (vital) para a educação Sandra Delmonte Gallego Honda1 Universidade Nove de Julho - UNINOVE Resumo: O presente artigo tem o objetivo de explanar de forma sucinta a biografia de Vital Brazil e relacionar suas contribuições na medicina e na educação brasileira. A educação, conforme é sabido, sofre defasagens consideráveis no cerne de alunos de escolas públicas que almejam adentrar em cursos superiores considerados, ainda hoje, elitistas, tal qual a medicina, que nos serve de protagonista neste trabalho. Buscou-se, assim, conjugar a biografia de Vital Brazil com as colocações de Paulo Freire em "Pedagogia do Oprimido" (2010), concluindo que a autonomia e a perseverança do educando diante das opressões e obstáculos são de suma importância para a concretização e a construção do indivíduo. Palavras-chave: Educação brasileira; pedagogia do oprimido; Vital Brazil Abstract: This paper its purpose explain a summarized form the Vital Brazil's biography and relate to their contributions in medicine with the Brazilian education. The education, as is known, suffers considerable gaps at the heart of public school students that aims to enter in university courses considered, even today, such elitists which medicine that serves the protagonist of this paper. It attempted to thus combine the biography of Vital Brazil with the placement of Paulo Freire in "Pedagogy of the Oppressed" (2010) concluding that the autonomy and perseverance of the student in front of oppression and obstacles are of paramount importance to the implementation and construction of the individual. Keywords: Brazilian education; pedagogy of the oppressed; Vital Brazil Introdução "A única felicidade da vida está na consciência de ter realizado algo útil em benefício da comunidade”. -

Approach and Management of Spider Bites for the Primary Care Physician

Osteopathic Family Physician (2011) 3, 149-153 Approach and management of spider bites for the primary care physician John Ashurst, DO,a Joe Sexton, MD,a Matt Cook, DOb From the Departments of aEmergency Medicine and bToxicology, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA. KEYWORDS: Summary The class Arachnida of the phylum Arthropoda comprises an estimated 100,000 species Spider bite; worldwide. However, only a handful of these species can cause clinical effects in humans because many Black widow; are unable to penetrate the skin, whereas others only inject prey-specific venom. The bite from a widow Brown recluse spider will produce local symptoms that include muscle spasm and systemic symptoms that resemble acute abdomen. The bite from a brown recluse locally will resemble a target lesion but will develop into an ulcerative, necrotic lesion over time. Spider bites can be prevented by several simple measures including home cleanliness and wearing the proper attire while working outdoors. Although most spider bites cause only local tissue swelling, early species identification coupled with species-specific man- agement may decrease the rate of morbidity associated with bites. © 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. More than 100,000 species of spiders are found world- homes and yards in the southwestern United States, and wide. Persons seeking medical attention as a result of spider related species occur in the temperate climate zones across bites is estimated at 50,000 patients per year.1,2 Although the globe.2,5 The second, Lactrodectus, or the common almost all species of spiders possess some level of venom, widow spider, are found in both temperate and tropical 2 the majority are considered harmless to humans. -

RES2 26.Pdf (687.3Kb)

PAN AMERICAN HEALTH SECOND MEETING ORGANIZATION 17-21 June 1963 Washington, D.C. ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON MEDICAL RESEARCH RESEARCH ACTIVITIES OF THE NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH, USPHS, IN LATIN AMERICA Ref: RES 2/26 24 May 1963 PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION Pan American Sanitary Bureau, Regional Office of the WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION WASHINGTON, D.C. RES 2/26 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page -4 1 Background 3 Regular Research Grants and Contracts 4 International Research Fellows from Latin America in the U.S.A. 5 U.S. Fellows and Trainees Abroad 6 Visiting Scientist Program 6 Special Foreign Currency Program 7 International Centers for Medical Research and Training (ICMRT) 8 Grants to PAHO 12 Tables I - X RES 2/26 RESEARCH AND RESEARCH TRAINING ACTIVITIES OF THE NIH/USPHS IN LATIN AMERICA DURING 1962 AND FUTURE TRENDS* During the first meeting of the PAHO Advisory Committee on Medical Research, June 18-22, 1962, the Chief of the Office of Inter- national Research, National Institutes of Health, USPHS, presented the general background, legislation, philosophy and objectives of all the international research activities of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), USPHS, RES 1/10. Since then, no significant changes in the legislative authority under which NIH operates overseas have taken place. Consequently, NIH objectives continue to be the ones formulated in Section 2, paragraph one, of the International Health Research Act of 1960 (P. L. 86-610): "To advance the status of the health sciences in the United States and thereby the health of the American people through cooperative en- deavors with the other countries in health re- search, and research training." It is important to keep this fact in mind in discussing the various activities undertaken by NIH in relation to Latin America. -

Antibody Response from Whole-Cell Pertussis Vaccine Immunized Brazilian Children Against Different Strains of Bordetella Pertussis

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 82(4), 2010, pp. 678–682 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0486 Copyright © 2010 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Antibody Response from Whole-Cell Pertussis Vaccine Immunized Brazilian Children against Different Strains of Bordetella pertussis Alexandre Pereira , Aparecida S. Pietro Pereira , Célio Lopes Silva , Gutemberg de Melo Rocha , Ivo Lebrun , Osvaldo A. Sant’Anna , and Denise V. Tambourgi * Genetics, Virology, Biochemistry and Immunochemistry Laboratories, Butantan Institute, São Paulo, Brazil; College of Medicine, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil Abstract. Bordetella pertussis is a gram-negative bacillus that causes the highly contagious disease known as pertussis or whooping cough. Antibody response in children may vary depending on the vaccination schedule and the product used. In this study, we have analyzed the antibody response of cellular pertussis vaccinated children against B. pertussis strains and their virulence factors, such as pertussis toxin, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin. After the completion of the immunization process, according to the Brazilian vaccination program, children serum samples were collected at different periods of time, and tested for the presence of specific antibodies and antigenic cross-reactivity. Results obtained show that children immunized with three doses of the Brazilian whole-cell pertussis vaccine present high levels of serum anti- bodies capable of recognizing the majority of the components present in vaccinal and non-vaccinal B. pertussis strains and their virulence factors for at least 2 years after the completion of the immunization procedure. INTRODUCTION Recent studies indicate that both immunization and infec- tion during childhood do not lead to a permanent immunity Bordetella pertussis is a gram-negative bacillus that causes against Bordetella pertussis and, as a consequence, older chil- the highly contagious disease known as pertussis or whoop- dren and adults are the main reservoirs of the infection. -

Nota Dos Editores / Editors' Notes

Nota dos Editores / Editors’ Notes Adolpho Lutz: complete works Jaime L. Benchimol Magali Romero Sá SciELO Books / SciELO Livros / SciELO Libros BENCHIMOL, JL., and SÁ, MR., eds., and orgs. Adolpho Lutz: Primeiros trabalhos: Alemanha, Suíça e Brasil (1878-1883) = First works: Germany, Switzerland and Brazil (1878-1883) [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FIOCRUZ, 2004. 440 p. Adolpho Lutz Obra Completa, v.1, book 1. ISBN: 85-7541-043-1. Available from SciELO Books <http://books.scielo.org>. All the contents of this work, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. Todo o conteúdo deste trabalho, exceto quando houver ressalva, é publicado sob a licença Creative Commons Atribuição - Uso Não Comercial - Partilha nos Mesmos Termos 3.0 Não adaptada. Todo el contenido de esta obra, excepto donde se indique lo contrario, está bajo licencia de la licencia Creative Commons Reconocimento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 3.0 Unported. PRIMEIROS TRABALHOS: ALEMANHA, SUÍÇA E NO BRASIL (1878-1883) 65 Adolpho Lutz : complete works The making of many books, my child, is without limit. Ecclesiastes 12:12 dolpho Lutz (1855-1940) was one of the most important scientists Brazil A ever had. Yet he is one of the least studied members of our scientific pantheon. He bequeathed us a sizable trove of studies and major discoveries in various areas of life sciences, prompting Arthur Neiva to classify him as a “genuine naturalist of the old Darwinian school.” His work linked the achievements of Bahia’s so-called Tropicalist School, which flourished in Salvador, Brazil’s former capital, between 1850 and 1860, to the medicine revolutionized by Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch, and Patrick Manson. -

Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming

toxins Review Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming Subodha Waiddyanatha 1,2, Anjana Silva 1,2 , Sisira Siribaddana 1 and Geoffrey K. Isbister 2,3,* 1 Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Saliyapura 50008, Sri Lanka; [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration, Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka 3 Clinical Toxicology Research Group, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +612-4921-1211 Received: 14 March 2019; Accepted: 29 March 2019; Published: 31 March 2019 Abstract: Long-term effects of envenoming compromise the quality of life of the survivors of snakebite. We searched MEDLINE (from 1946) and EMBASE (from 1947) until October 2018 for clinical literature on the long-term effects of snake envenoming using different combinations of search terms. We classified conditions that last or appear more than six weeks following envenoming as long term or delayed effects of envenoming. Of 257 records identified, 51 articles describe the long-term effects of snake envenoming and were reviewed. Disability due to amputations, deformities, contracture formation, and chronic ulceration, rarely with malignant change, have resulted from local necrosis due to bites mainly from African and Asian cobras, and Central and South American Pit-vipers. Progression of acute kidney injury into chronic renal failure in Russell’s viper bites has been reported in several studies from India and Sri Lanka. Neuromuscular toxicity does not appear to result in long-term effects. -

Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: a Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms

Journal of Heredity 2006:97(3):206–217 ª The American Genetic Association. 2006. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/jhered/esj034 For permissions, please email: [email protected]. Advance Access publication June 1, 2006 Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: A Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms WILLIAM LEO SMITH AND WARD C. WHEELER From the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology, Columbia University, 1200 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, NY 10027 (Leo Smith); Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Ichthyology), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Leo Smith); and Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Wheeler). Address correspondence to W. L. Smith at the address above, or e-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Knowledge of evolutionary relationships or phylogeny allows for effective predictions about the unstudied characteristics of species. These include the presence and biological activity of an organism’s venoms. To date, most venom bioprospecting has focused on snakes, resulting in six stroke and cancer treatment drugs that are nearing U.S. Food and Drug Administration review. Fishes, however, with thousands of venoms, represent an untapped resource of natural products. The first step in- volved in the efficient bioprospecting of these compounds is a phylogeny of venomous fishes. Here, we show the results of such an analysis and provide the first explicit suborder-level phylogeny for spiny-rayed fishes. The results, based on ;1.1 million aligned base pairs, suggest that, in contrast to previous estimates of 200 venomous fishes, .1,200 fishes in 12 clades should be presumed venomous.