Radical Contact Prints-Revised

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 04 Newsletter

United States Atmospheric & Underwater Atomic Weapon Activities National Association of Atomic Veterans, Inc. 1945 “TRINITY“ “Assisting America’s Atomic Veterans Since 1979” ALAMOGORDO, N. M. Website: www.naav.com E-mail: [email protected] 1945 “LITTLE BOY“ HIROSHIMA, JAPAN R. J. RITTER - Editor April, 2012 1945 “FAT MAN“ NAGASAKI, JAPAN 1946 “CROSSROADS“ BIKINI ISLAND 1948 “SANDSTONE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “RANGER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1951 “GREENHOUSE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “BUSTER – JANGLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “TUMBLER - SNAPPER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “IVY“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1953 “UPSHOT - KNOTHOLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1954 “CASTLE“ BIKINI ISLAND 1955 “TEAPOT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1955 “WIGWAM“ OFFSHORE SAN DIEGO 1955 “PROJECT 56“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1956 “REDWING“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1957 “PLUMBOB“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1958 “HARDTACK-I“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1958 “NEWSREEL“ JOHNSTON ISLAND 1958 “ARGUS“ SOUTH ATLANTIC 1958 “HARDTACK-II“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1961 “NOUGAT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1962 “DOMINIC-I“ CHRISTMAS ISLAND JOHNSTON ISLAND 1965 “FLINTLOCK“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1969 “MANDREL“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1971 “GROMMET“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1974 “POST TEST EVENTS“ ENEWETAK CLEANUP ------------ “ IF YOU WERE THERE, YOU ARE AN ATOMIC VETERAN “ The Newsletter for America’s Atomic Veterans COMMANDER’S COMMENTS knowing the seriousness of the situation, did not register any Outreach Update: First, let me extend our discomfort, or dissatisfaction on her part. As a matter of fact, it thanks to the membership and friends of NAAV was kind of nice to have some of those callers express their for supporting our “outreach” efforts over the thanks for her kind attention and assistance. We will continue past several years. It is that firm dedication to to insure that all inquires, along these lines, are fully and our Mission-Statement that has driven our adequately addressed. -

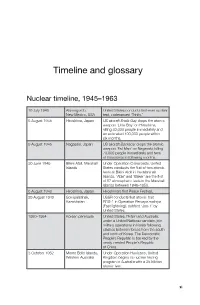

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

Trinity and Beyond: the Atomic Bomb Movie

Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie 1. Why did scientists detonate 100 tons of TNT be- 9. How many died in Hiroshima? 20. How heavy was the housing that contained the fore they tested their bombs? Mike test bomb? 10. How many buildings were destroyed? 2. Who was put in charge of the Manhattan Project? 21. During the 1953 Nevada desert tests, why did the smaller yield bomb cause more damage than the 11. How many died in Nagasaki? larger yield bomb? 3. Was the scientist Edward Teller at first in favor of the bomb project? 12. How many were injured? 22. What were the scientists studying when they ex- ploded bombs in the ocean off of San Diego? 4. Did he ever regret working on the bombs? 13. What percent of the buildings were destroyed? 23. On later Pacific Island tests, why were floating 5. When the first test bomb exploded at the Trinity barges needed to carry the bombs? site in New Mexico, what were the values associated 14. During Operation Crossroads, which caused with each of the following? more damage; the airdrop, or the underwater explo- sion? 24. How high up was the Teak test shot detonated? a) temperature: b) pressure: 15. What was the purpose of Operation Sandstone? 25. What happened in the atmosphere as a result? c) distance at which a person would go temporarily blind: d) number of times greater than the explosion of 100 16. In what year did Russia first test an atomic 26. How far away were these effects felt, and how tons of TNT: bomb? long did they last? 6. -

Tomoe Otsuki

Volume 13 | Issue 32 | Number 2 | Article ID 4356 | Aug 10, 2015 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Politics of Reconstruction and Reconciliation in U.S-Japan Relations—Dismantling the Atomic Bomb Ruins of Nagasaki’s Urakami Cathedral Tomoe Otsuki Abstract: This paper explores the politics surrounding the dismantling of the ruins of Nagasaki’s Urakami Cathedral. It shows how U.S-Japan relations in the mid-1950s shaped the 1958 decision by the Catholic community of Urakami to dismantle and subsequently to reconstruct the ruins. The paper also assesses the significance of the struggle over the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral for understanding the respective responses to atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It further casts new light on the wartime role of the Catholic Church and of Nagai Takashi. Keywords: Nagasaki, Atomic Bomb, Urakami Cathedral, the People-to-People program, Lucky Dragon # 5 incident, Japanese antinuclear movement, the peaceful use of nuclear energy, sister city relation between Nagasaki and St. Paul, U.S.-Japan Security Alliance. The two photographs below depict the remnants of the Urakami Cathedral following the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Both were taken in 1953 by Takahara Itaru, a former Mainichi Shimbun photographer as well as a Remnants of the Southern Wall and statues of the Nagasaki hibakusha. Most of the children saints of Urakami Cathedral playing beside the ruins were born after the Photo courtesy of Takahara Itaru atomic bombing and grew up in Urakami’s atomic field. Takahara’s photographs capture the remnants of the cathedral in shaping the Children play in remnants of belfry of Urakami postwar landscape and lives of people in and Cathedral 1 around Urakami. -

Smithsonian and the Enola

An Air Force Association Special Report The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay The Air Force Association The Air Force Association (AFA) is an independent, nonprofit civilian organiza- tion promoting public understanding of aerospace power and the pivotal role it plays in the security of the nation. AFA publishes Air Force Magazine, sponsors national symposia, and disseminates infor- mation through outreach programs of its affiliate, the Aerospace Education Founda- tion. Learn more about AFA by visiting us on the Web at www.afa.org. The Aerospace Education Foundation The Aerospace Education Foundation (AEF) is dedicated to ensuring America’s aerospace excellence through education, scholarships, grants, awards, and public awareness programs. The Foundation also publishes a series of studies and forums on aerospace and national security. The Eaker Institute is the public policy and research arm of AEF. AEF works through a network of thou- sands of Air Force Association members and more than 200 chapters to distrib- ute educational material to schools and concerned citizens. An example of this includes “Visions of Exploration,” an AEF/USA Today multi-disciplinary sci- ence, math, and social studies program. To find out how you can support aerospace excellence visit us on the Web at www. aef.org. © 2004 The Air Force Association Published 2004 by Aerospace Education Foundation 1501 Lee Highway Arlington VA 22209-1198 Tel: (703) 247-5839 Produced by the staff of Air Force Magazine Fax: (703) 247-5853 Design by Guy Aceto, Art Director An Air Force Association Special Report The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay By John T. Correll April 2004 Front cover: The huge B-29 bomber Enola Gay, which dropped an atomic bomb on Japan, is one of the world’s most famous airplanes. -

Bob Farquhar

1 2 Created by Bob Farquhar For and dedicated to my grandchildren, their children, and all humanity. This is Copyright material 3 Table of Contents Preface 4 Conclusions 6 Gadget 8 Making Bombs Tick 15 ‘Little Boy’ 25 ‘Fat Man’ 40 Effectiveness 49 Death By Radiation 52 Crossroads 55 Atomic Bomb Targets 66 Acheson–Lilienthal Report & Baruch Plan 68 The Tests 71 Guinea Pigs 92 Atomic Animals 96 Downwinders 100 The H-Bomb 109 Nukes in Space 119 Going Underground 124 Leaks and Vents 132 Turning Swords Into Plowshares 135 Nuclear Detonations by Other Countries 147 Cessation of Testing 159 Building Bombs 161 Delivering Bombs 178 Strategic Bombers 181 Nuclear Capable Tactical Aircraft 188 Missiles and MIRV’s 193 Naval Delivery 211 Stand-Off & Cruise Missiles 219 U.S. Nuclear Arsenal 229 Enduring Stockpile 246 Nuclear Treaties 251 Duck and Cover 255 Let’s Nuke Des Moines! 265 Conclusion 270 Lest We Forget 274 The Beginning or The End? 280 Update: 7/1/12 Copyright © 2012 rbf 4 Preface 5 Hey there, I’m Ralph. That’s my dog Spot over there. Welcome to the not-so-wonderful world of nuclear weaponry. This book is a journey from 1945 when the first atomic bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert to where we are today. It’s an interesting and sometimes bizarre journey. It can also be horribly frightening. Today, there are enough nuclear weapons to destroy the civilized world several times over. Over 23,000. “Enough to make the rubble bounce,” Winston Churchill said. The United States alone has over 10,000 warheads in what’s called the ‘enduring stockpile.’ In my time, we took care of things Mano-a-Mano. -

2016 2Nd Quarter NEWSLETTER 1

United States Atmospheric & Underwater Atomic Weapon Activities National Association of Atomic Veterans, Inc. 1945 “TRINITY“ “Assisting America’s Atomic Veterans Since 1979” ALAMOGORDO, N. M. Website: www.naav.com E-mail: [email protected] 1945 “LITTLE BOY“ HIROSHIMA, JAPAN R. J. RITTER - Editor November, 2011 1945 “FAT MAN“ NAGASAKI, JAPAN 1946 “CROSSROADS“ BIKINI ISLAND 1948 “SANDSTONE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “RANGER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1951 “GREENHOUSE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “BUSTER – JANGLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “TUMBLER - SNAPPER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “IVY“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1953 “UPSHOT - KNOTHOLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1954 “CASTLE“ BIKINI ISLAND 1955 “TEAPOT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1955 “WIGWAM“ OFFSHORE SAN DIEGO 1955 “PROJECT 56“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1956 “REDWING“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI “ Hey Sarge - I can still feel the heat “ 1957 “PLUMBOB“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1958 “HARDTACK-I“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1958 “NEWSREEL“ JOHNSON ISLAND 1958 “ARGUS“ SOUTH ATLANTIC 1958 “HARDTACK-II“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1961 “NOUGAT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1962 “DOMINIC-I“ CHRISTMAS ISLAND JOHNSTON ISLAND 1965 “FLINTLOCK“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1969 “MANDREL“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1971 “GROMMET“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1974 “POST TEST EVENTS“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA ------------ “ IF YOU WERE THERE, The motto of the day was “Semper-Fry“ YOU ARE AN ATOMIC VETERAN “ The Newsletter for America’s Atomic Veterans COMMANDERS COMMENTS We enjoyed our re-union in Richmond, VA and wish to offer our thanks to Director Jenkins for his efforts to make this event an Ted Hayes ( AZ ) Clarence Roth ( CT ) overwhelming success. Gillie furnished a Howard Shertzer ( PA ) Paul Bochon ( WA ) bus for an all-day ( ladies-only ) tour of the Robert Hosley ( CA ) John E. Forde ( CA ) local historical sites. -

Still More Radical Changes at Y-12

Still more radical changes at Y-12 In the months after the war ended, change was not limited to Y-12 or just to Oak Ridge, Tennessee. While the folks at Y-12 were experiencing tremendous upheaval through major changes in workforce levels, stopping the major program of uranium separation, starting stable isotope separation and trying to determine what the future held for Y-12, other major transitions were taking place all across the nation. World War II was over, but hardly had that begun to sink in when the realization and fear that someone else would surely develop an atomic weapon caused expansion of atomic energy research as well as expanded production facilities for nuclear weapons. The Cold War was not known as that just yet, but fear of what the Russians would do was not a new idea. As the results of investigations into the German and Japanese atomic energy research after the war ended, it was determined that Germany did not have a viable program and neither did Japan. However, evidence was found that indicated that both were actively pursuing atomic weapons. All the Manhattan Project sites experienced radical changes during this transition from the war production period of unlimited funding and schedule pressure beyond anything that could be understood today. General Groves stayed close to the decisions at each site and worked the issues of transitioning from war time operating contractors to new companies. This was no small task. At Los Alamos, the primary problem was that of Oppenheimer’s leaving. He had been the key leader for the scientists there. -

Operation Crossroads: a Report of Non-Participating Scientific Observer

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3z09r4zz No online items Operation Crossroads: a report of non-participating scientific observer Paul S. Galtsoff The University Library Special Collections and Archives University Library University of California, Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, California, 95064 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucsc.edu/speccoll/ © 2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Operation Crossroads: a report of MS 294 1 non-participating scientific observer Operation Crossroads: a report of non-participating scientific observer Collection number: MS 294 The University Library Special Collections and Archives University of California, Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, California Processed by: UCSC OAC Unit Date Completed: May 15, 2008 Encoded by: UCSC OAC Unit © 2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Operation Crossroads: a report of non-participating scientific observer Dates: 1946-1947 Collection number: MS 294 Creator: Galtsoff, Paul S. Collection Size: 74 pages 1 portfolio Repository: University of California, Santa Cruz. University Library. Special Collections and Archives Santa Cruz, California 95064 Abstract: This collection includes annotated typescript and photographs of Galtsoff's report as an observer of the Bikini Atoll atomic bomb tests and the destructive results of the tests on the sea life in the area. Physical location: Stored offsite at NRLF: Advance notice is required for access to the papers. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection open for research. Publication Rights Property rights reside with the University of California. Literary rights are retained by the creators of the records and their heirs. -

The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb” Is a Short History of the Origins and Develop- Ment of the American Atomic Bomb Program During World War H

f.IOE/MA-0001 -08 ‘9g [ . J vb JMkirlJkhilgUimBA’mmml — .— Q RDlmm UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY ,:.. .- ..-. .. -,.,,:. ,.<,.;<. ~-.~,.,.- -<.:,.:-,------—,.--,,p:---—;-.:-- ---:---—---- -..>------------.,._,.... ,/ ._ . ... ,. “ .. .;l, ..,:, ..... ..’, .’< . Copies of this publication are available while supply lasts from the OffIce of Scientific and Technical Information P.O. BOX 62 Oak Ridge, TN 37831 Attention: Information Services Telephone: (423) 576-8401 Also Available: The United States Department of Energy: A Summary History, 1977-1994 @ Printed with soy ink on recycled paper DO13MA-0001 a +~?y I I Tho PROJEOT UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY F.G. Gosling History Division Executive Secretariat Management and Administration Department of Energy ]January 1999 edition . DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. I DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. 1 Foreword The Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977 brought together for the first time in one department most of the Federal Government’s energy programs. -

Identifying Ships in Photos of the Baker Nuclear Test

VOICES Identifying ships in photos of the Baker nuclear test BY MICHAEL BÜKER, PHYSICIST AND SCIENCE COMMUNICATOR The "Baker" explosion, part of Operation Crossroads, a nuclear weapon test by the United States military at Bikini Atoll, Micronesia, on 25 July 1946. Source: Wikimedia Commons. This photograph above is probably one the most notable were the Japanese seafaring countries. In my opinion, of the best known and most impressive battleship Nagato, the German however, the Memorial does not do when it comes to illustrating the scale cruiser Prinz Eugen and the U.S. a very convincing job of renouncing and impact of a nuclear test ‒ even if aircraft carrier Saratoga. After the the glorification and romanticization the explosion was a small one even by two test explosions, all three ‒ and of murderous naval warfare and the standards of the 1960s. It shows several more ships ‒ eventually sank truly exhibiting an international and the fifth-ever explosion of a nuclear and were abandoned for being too intercultural spirit. bomb, about two years after the first- radioactive to salvage. ever nuclear explosion in the Trinity After seeing the propeller, I test and one year after the attacks on A part of one of those ships, wanted to pick out the Prinz Eugen in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. salvaged over 30 years after the nuclear photographs of the Crossroads nuclear tests, has been on display in northern tests. There did not seem to be, however, Military ships were placed in Germany close to where I live, since any annotated photographs detailing the vicinity of the two explosions 1979. -

Making the Russian Bomb from Stalin to Yeltsin

MAKING THE RUSSIAN BOMB FROM STALIN TO YELTSIN by Thomas B. Cochran Robert S. Norris and Oleg A. Bukharin A book by the Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. Westview Press Boulder, San Francisco, Oxford Copyright Natural Resources Defense Council © 1995 Table of Contents List of Figures .................................................. List of Tables ................................................... Preface and Acknowledgements ..................................... CHAPTER ONE A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SOVIET BOMB Russian and Soviet Nuclear Physics ............................... Towards the Atomic Bomb .......................................... Diverted by War ............................................. Full Speed Ahead ............................................ Establishment of the Test Site and the First Test ................ The Role of Espionage ............................................ Thermonuclear Weapons Developments ............................... Was Joe-4 a Hydrogen Bomb? .................................. Testing the Third Idea ...................................... Stalin's Death and the Reorganization of the Bomb Program ........ CHAPTER TWO AN OVERVIEW OF THE STOCKPILE AND COMPLEX The Nuclear Weapons Stockpile .................................... Ministry of Atomic Energy ........................................ The Nuclear Weapons Complex ...................................... Nuclear Weapon Design Laboratories ............................... Arzamas-16 .................................................. Chelyabinsk-70