In It for the Long Haul? Lessons on Peacebuilding in South Sudan Acknowledgments – the Team Behind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Draft of the Co-Chairman's Statement

FINAL DRAFT OF THE CO-CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT Your Excellencies, Honorable Delegates, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, On behalf of my Co-Chairman, Moulana Abel Alier, my colleagues in the Steering Committee, and on my own behalf, I would like to extend a warm welcome to all of you to this Conference, which marks the final phase of the National Dialogue. This is a historic occasion for us in the National Dialogue and we believe for our country. When His Excellency, President Salva Kiir Mayardit, initiated the National Dialogue more than three years ago, we cannot say with confidence that we, or anyone else for that matter, had a clear idea how long it would take, where it would lead, and what the end result would be. It was initially thought that the Dialogue process would take several months. Many saw it as a ploy by the President to polish his political image. The National Dialogue has now lasted for over three years. And far from being a ploy by the President, it has proved to be a sincere national soul searching about the crises facing our country. 1 What we soon learned as we undertook our assignment, was that our President wanted the process to be absolutely free, inclusive, transparent and credible. He repeatedly reaffirmed that National Dialogue was not a trap or a net for catching his political opponents, and that people should speak freely without fear, harassment or any form of intimidation. And, indeed, through the nationwide grassroots consultations and regional conferences, our people spoke their minds without fear or constraint. -

Warrap State SOUTH SUDAN

COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Warrap State SOUTH SUDAN Bureau for Community Security South Sudan Peace and Small Arms Control and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme The Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control under the Ministry of Interior is the Gov- ernment agency of South Sudan mandated to address the threats posed by the proliferation of small arms and community insecurity to peace and development. The South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission is mandated to promote peaceful co-existence amongst the people of South Sudan and advise the Government on matters related to peace. The United Nations Development Programme in South Sudan, through the Community Security and Arms Control Project supports the Bureau strengthen its capacity in the area of community security and arms control at the national, state, and county levels. Cover photo: © UNDP/Sun-Ra Lambert Baj COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Warrap State South Sudan Published by South Sudan Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme MAY 2012 JUBA, SOUTH SUDAN CONTENTS Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... i Foreword ........................................................................................................................... .ii Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... -

Solar Powered Transmission: a Case Study from South Sudan

Figure 1 – Solar Panels, viewed from above Solar Powered Transmission: A Case Study from South Sudan By Issa Kassimu, Natalie Chang and Ann Charles On behalf of The Radio Community and Internews Version 1.0, November 2016 About The Radio Community The Radio Community (TRC) is a network of community radio stations in South Sudan that reach an estimated 2.1 million potential listeners. These include Mayardit FM in Turalei, Warrap State; Nhomlaau FM in Malualkon, Northern Bahr el Ghazal State; Singaita FM in Kapoeta, Eastern Equatoria State; Mingkaman FM in Awerial County, Lakes State; and Nile FM in Malakal, Upper Nile State (operated in partnership with Internews’ Humanitarian Information Services). Stations in Leer and Nasir are currently off-air due to conflict. About Internews Internews is an international non-profit organization whose mission is to empower local media worldwide to give people the news and information they need, the ability to connect and the means to make their voices heard. Internews provides communities the resources to produce local news and information with integrity and independence. With global expertise and reach, Internews trains both media professionals and citizen journalists, introduces innovative media solutions, increases coverage of vital issues and helps establish policies needed for open access to information. Internews operates internationally, with administrative centers in California, Washington DC, and London, as well as regional hubs in Bangkok and Nairobi. Formed in 1982, Internews has worked in more than 90 countries, and currently has offices in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Latin America and North America. Internews Network is registered as a 501(c)3 organization in California, EIN 94-302-7961. -

Strategic Peacebuilding- the Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan

SPECIAL REPORT Strategic Peacebuilding The Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan The Cases of the SPLM Leadership Crisis (2013), the Military Standoff at General Malong’s House (2017), and the Wau Crisis (2016–17) NYATHON H. MAI JULY 2020 WEEKLY REVIEW June 7, 2020 The Boiling Frustrations in South Sudan Abraham A. Awolich outh Sudan’s 2018 peace agreement that ended the deadly 6-year civil war is in jeopardy, both because the parties to it are back to brinkmanship over a number S of mildly contentious issues in the agreement and because the implementation process has skipped over fundamental st eps in a rush to form a unity government. It seems that the parties, the mediators and guarantors of the agreement wereof the mind that a quick formation of the Revitalized Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) would start to build trust between the leaders and to procure a public buy-in. Unfortunately, a unity government that is devoid of capacity and political will is unable to address the fundamentals of peace, namely, security, basic services, and justice and accountability. The result is that the citizens at all levels of society are disappointed in RTGoNU, with many taking the law, order, security, and survival into their own hands due to the ubiquitous absence of government in their everyday lives. The country is now at more risk of becoming undone at its seams than any other time since the liberation war ended in 2005. The current st ate of affairs in the country has been long in the making. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

Sudan: Colonialism, Independence, and Conflict

Sudan: Colonialism, Independence, and Conflict Overview Students will analyze the impact of colonization on Sudan including regional divisions, independence movements, and conflict. Students will understand the various economic, political, and societal factors that have led to wars in the region. Students will also learn that these conflicts have led to migration out of Sudan, exploring cultural and artistic production of Sudanese people in the diaspora. Students will learn that the effects of decolonization and ethnic conflict have been a push factor for African migration in the new wave of diaspora. Essential/Compelling Question(s) How has the legacy of colonization and imperialism impacted Sudan? How has conflict in Sudan affected the country’s politics, economy, and society? How are human rights affected in times of conflict? Grade(s) 9-12 Subject(s) World History North Carolina Essential Standards WH.8: Analyze global interdependence and shifts in power in terms of political, economic, social and environmental changes and conflicts since the last half of the twentieth century. WH.H.8.3: Analyze the "new" balance of power and the search for peace and stability in terms of how each has influenced global interactions since the last half of the twentieth century (e.g., post WWII, Post Cold War, 1990s Globalization, New World Order, Global Achievements and Innovations). WH.8.6: Explain how liberal democracy, private enterprise and human rights movements have reshaped political, economic and social life in Africa, Asia, Latin America, Europe, the Soviet Union and the United States (e.g., U.N. Declaration of Human Rights, end of Cold War, apartheid, perestroika, glasnost, etc.). -

1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: http://www.au.int/en/auciss Original: English FINAL REPORT OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SOUTH SUDAN ADDIS ABABA 15 OCTOBER 2014 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER II .................................................................................................................. 34 INSTITUTIONS IN SOUTH SUDAN .............................................................................. 34 CHAPTER III ............................................................................................................... 110 EXAMINATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND OTHER ABUSES DURING THE CONFLICT: ACCOUNTABILITY ......................................................................... 111 CHAPTER IV ............................................................................................................... 233 ISSUES ON HEALING AND RECONCILIATION ....................................................... -

Download UA In

UA: 100/19 Index: AFR 65/0679/2019 South Sudan Date: 10 July 2019 URGENT ACTION SECURITY AGENT ILL-TREATED IN DETENTION Ding Ding Mou, a South Sudanese security agent, is detained at the Riverside detention centre – notorious for its extremely poor conditions and incidents of torture and other forms of ill-treatment. He was arbitrarily arrested by the National Security Service (NSS) in Juba on 31 May. He was first detained at the NSS headquarters, known as ‘Blue House’ for eight days. TAKE ACTION: WRITE AN APPEAL IN YOUR OWN WORDS OR USE THIS MODEL LETTER President of the Republic of South Sudan Salva Kiir Mayardit Juba, South Sudan Twitter: @RepSouthSudan and @PresSalva Your Excellency President Salva Kiir, Ding Ding Mou, a South Sudanese staff member of the National Security Service (NSS), was arbitrarily arrested by the NSS in Juba on 31 May. He was first detained at the NSS headquarters, known as ‘Blue House’ for eight days before being transferred to the Riverside detention centre – notorious for its extremely poor conditions and incidents of torture and other forms of ill-treatment – on 8 June. Ding Ding Mou has been denied family visits and access to a lawyer. He has also not been informed of any charges against him. Amnesty International has received credible reports that he is detained at Riverside detention centre where he is being held in a small room described as a mosquito infested “cage” where he sleeps leaning on the wall and is forced to drink water from the toilet. Amnesty International is concerned that his health condition has deteriorated over the past month due to conditions of detention and there are concerns that he is not receiving the medical treatment he needs. -

Village Assessment Survey Twic County

Village Assessment Survey COUNTY ATLAS 2013 Twic County Warrap State Village Assessment Survey The Village Assessment Survey (VAS) has been used by IOM since 2007 and is a comprehensive data source for South Sudan that provides detailed information on access to basic services, infra- structure and other key indicators essential to informing the development of efficient reintegra- tion programmes. The most recent VAS represents IOM’s largest effort to date encompassing 30 priority counties comprising of 871 bomas, 197 payams, 468 health facilities, and 1,277 primary schools. There was a particular emphasis on assessing payams outside state capitals, where com- paratively fewer comprehensive assessments have been carried out. IOM conducted the assess- ment in priority counties where an estimated 72% of the returnee population (based on esti- mates as of 2012) has resettled. The county atlas provides spatial data at the boma level and should be used in conjunction with the VAS county profile. Four (4) Counties Assessed Planning Map and Dashboard..…………Page 1 WASH Section…………..………...Page 14 - 20 General Section…………...……...Page 2 - 5 Natural Source of Water……...……….…..Page 14 Main Ethnicities and Languages.………...Page 2 Water Point and Physical Accessibility….…Page 15 Infrastructure and Services……...............Page 3 Water Management & Conflict....….………Page 16 Land Ownership and Settlement Type ….Page 4 WASH Education...….……………….…….Page 17 Returnee Land Allocation Status..……...Page 5 Latrine Type and Use...………....………….Page 18 Livelihood Section…………..…...Page -

The Religious Landscape in South Sudan CHALLENGES and OPPORTUNITIES for ENGAGEMENT by Jacqueline Wilson

The Religious Landscape in South Sudan CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR ENGAGEMENT By Jacqueline Wilson NO. 148 | JUNE 2019 Making Peace Possible NO. 148 | JUNE 2019 ABOUT THE REPORT This report showcases religious actors and institutions in South Sudan, highlights chal- lenges impeding their peace work, and provides recommendations for policymakers RELIGION and practitioners to better engage with religious actors for peace in South Sudan. The report was sponsored by the Religion and Inclusive Societies program at USIP. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jacqueline Wilson has worked on Sudan and South Sudan since 2002, as a military reserv- ist supporting the Comprehensive Peace Agreement process, as a peacebuilding trainer and practitioner for the US Institute of Peace from 2004 to 2015, and as a Georgetown University scholar. She thanks USIP’s Africa and Religion and Inclusive Societies teams, Matthew Pritchard, Palwasha Kakar, and Ann Wainscott for their support on this project. Cover photo: South Sudanese gather following Christmas services at Kator Cathedral in Juba. (Photo by Benedicte Desrus/Alamy Stock Photo) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2019 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. 148. First published 2019. -

Initial Rapid Needs Assessment Report Internally Displaced Persons in Twic County Warrap from Unity State 3 January 2014

IRNA Report Twic IDPs from Unity State 3 Jan 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment Report Internally Displaced Persons in Twic County Warrap from Unity State 3 January 2014 Important: - IRNA Report should include secondary data collected by all stakeholders and jointly analyzed - IRNA Report should also include community level assessment analysis by clusters and then jointly analyzed by all stakeholders - Report should adequately cover the de-briefing analysis of assessment team leaders - This report should be produced within two days after the IRNA taking place 1 IRNA Report Twic IDPs from Unity State 3 Jan 2014 Situation Overview (use the secondary information as well as the information gathered under the ‘Generalist’ section of the IRNA questionnaire. Map Drivers of Crisis and underlying factors Place map of affected area if available Conflict has spread across South Sudan following an alleged coup attempt three weeks ago in Juba. Among the states directly affected by the crisis is Unity State which neighbours Warrap State to the East. An influx of Internally Displaced People (IDPs) into Warrap’s Twic County has steadily increased since the last week of December Affected population: 2013. Most of those IDPs have been directly attacked or been caught (appox. Male/female and boys/girls) up in the cross fire during the fighting that has ensued in Unity State, while some have run out of seer fear. Displaced population: (appox. Male/female and boys/girls) Scope of crisis and humanitarian profile Most of the displaced are from Mayom County in Unity State, while 3,215 individuals some have been displaced from as far as Bentiu town the Unity State with possible increase in coming days capital itself, in Rubkona County. -

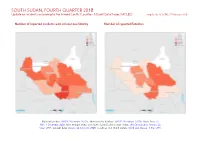

SOUTH SUDAN, FOURTH QUARTER 2018: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020

SOUTH SUDAN, FOURTH QUARTER 2018: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SS- NBS, 1 December 2008; Ilemi triangle status and South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, Oc- tober 2011; incident data: ACLED, 22 February 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SOUTH SUDAN, FOURTH QUARTER 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 120 48 142 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 84 49 156 Development of conflict incidents from December 2016 to December 2018 2 Strategic developments 18 0 0 Protests 6 0 0 Methodology 3 Explosions / Remote 2 1 2 Conflict incidents per province 4 violence Riots 2 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 232 98 300 Disclaimer 5 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2016 to December 2018 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). 2 SOUTH SUDAN, FOURTH QUARTER 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Methodology sources if necessary.