N E W S L E T T E R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Public Value of the Humanities

Breward, Christopher. "A Museum Perspective." The Public Value of the Humanities. Ed. Jonathan Bate. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011. 171–183. The WISH List. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849662451.ch-013>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 23:09 UTC. Copyright © Jonathan Bate and contributors 2011. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 171 13. A Museum Perspective Christopher Breward (Victoria and Albert Museum) Arts and humanities research directly informs the key activities of a national museum like the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A). The museum serves as an international centre of excellence in the fi elds of the history of art and design, conservation, learning and interpretation and contemporary creative practice, and its programmes benefi t from research that is designed to contribute both to the public understanding and experience of its collections, and to the methodological and theoretical advancement of relevant arts and humanities disciplines. The V&A therefore fosters a proactive research culture, both in developing public outcomes that are underpinned by current scholarship (its galleries, high-profi le exhibitions, publications, conferences and website) and in fostering collaborations with academic partners. As a frequent recipient of Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and other research grants the V&A is well practised in recognizing and capitalizing on opportunities to enhance the value of its activities and outputs through ambitious, authoritative and accessible research programmes. -

Fine Arts Museums Foundation

APPENDIX I FINE ARTS MUSEUMS FOUNDATION Report of Acquisitions Committee October 2, 2018 Page PURCHASES…………………………………………………. 1 American Art – 1 Ancient Art - 1 Achenbach Prints and Drawings - 39 Total Purchases - 41 FUNDED PURCHASES………………………………………... 2 Achenbach - Prints and Drawings – 45 Total Funded Purchases - 45 GIFTS…………………………………………………………. 3 Achenbach – Photography – 21 Achenbach – Prints and Drawings – 152 Costume and Textile Arts – 6 Total Gifts – 179 FIRST STEP DEACCESSIONS……………………………. 4 American Art – 48 Total First Step Deaccessions – 48 SECOND STEP DEACCESSIONS……………………………. 5 American Art – 18 Total Second Step Deaccessions – 18 Prepared for 10-30-2018 BT Fine Arts Museums Foundation Acquisitions Committee October 2, 2018 PURCHASES American Art Josef Albers, American, 1888–1976 Blue Front, 1948-1955 Oil on masonite 23 3/4 x 34 1/2 inches (60.3 x 87.6 cm) Museum purchase, Vivien Grey Fund for Unrestricted Acquisitions, Friends of Ian White Unrestricted Endowment Income Fund, Dr. Leland A. & Gladys K. Barber Endowment Income Fund, Gifts for Acquisitions at the de Young Museum, the American Art Trust Fund, and the Harriet and Maurice Gregg Fund for American Abstract Art L18.47 Ancient Art Timurid Panel in the Shape of a Mihrab, second half of 14th century Timurid, Western Central Asia Carved and glazed terracotta 55.5 x 40 x 5 cm (21 7/8 x 15 3/4 x 1 15/16 in.) Museum purchase, Museum Purchase, Vivian Grey Fund for Unrestricted Acquisitions and Friends of Ian White Restricted Endowment Income Fund L18.57 Achenbach – Prints and Drawings Kehinde Wiley, American, b. 1977 Lapis Press (printer), American, b. 1984 Tomb of Pope Alexander VII Study I, 2016 Sophie Arnould Study II, 2016 Hand embellished pigment print 686 x 508 mm (27 x 20 in.) Museum purchase, gift of the Achenbach Graphic Arts Council L18.48.1-2 Toyin Ojih Odutola, Nigerian, active United States, b. -

LondonArtFairCollaboratesWithOfficialMuseum PartnerArtUkToSt

PRESS RELEASE: Under embargo until Thursday 19 October, 09:00 hrs (BST) LONDON ART FAIR COLLABORATES WITH OFFICIAL MUSEUM PARTNER ART UK TO STAGE SPECIAL EXHIBITION IN CELEBRATION OF 30 YEARS ● Five leading contemporary artists - Sonia Boyce, Mat Collishaw, Haroon Mirza, Oscar Murillo and Rose Wylie - select works from Art UK for one-off exhibition at London Art Fair 2018 ● ‘Art of the Nation: Five Artists Choose’ is the first exhibition staged by digital platform Art UK, to showcase public collections across the UK ● Art UK is the official Museum Partner of London Art Fair, which will present leading British and international galleries alongside curated spaces from 17 - 21 January 2018 (Preview 16 January) In celebration of its 30th anniversary, London Art Fair has partnered with Art UK to stage a unique exhibition highlighting 30 remarkable works from the nation’s public art collections. As the Fair’s official 2018 Museum Partner, Art UK will present its first ever exhibition - ‘Art of the Nation: Five Artists Choose’ - from 17 - 21 January 2018. Reflecting the mission of the charity and its digital platform - the show will shine a spotlight on the rich and diverse regional collections showcased on artuk.org, the online home to every public art collection in the UK, which features over 200,000 artworks from over 3,250 venues. In an exhibition curated by Kathleen Soriano, Art UK has invited five leading contemporary artists to each select 20th and 21st century works from the Art UK online platform. Each artist has chosen up to six works within a theme that is both personal and speaks to their individual interests. -

Curriculum Vita (PDF)

Winston Branch Born Castries, ST. Lucia, West Indies, 1947 (British citizen) Education 1971-1972 The British School at Rome, Italy 1966-1970 Slade School of Fine Art, University College London, England Teaching 2000-2001 Associate Professor, Kansas State University, USA 1998-1999 Assistant Adjunct Professor, University of California at Berkeley 1973-1992 Visiting Tutor, Slade School of Fine Art, University College, London, England Visiting Tutor, Chelsea Art School, London, England Visiting Tutor, Kingston Art School, London, England 1973 Artist-in-Residence, Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee 1971 Visiting Tutor, Goldsmith’s College or Art, London University, England Visiting Tutor, Hornsey College of Art, London, England Public Lectures May 2002 “Artists Talk” Oakland Museum of California, Oakland, California Public talk. Sep. 2000 Visiting Artists lecture series, Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University Feb, 2000 “Modernity out of the calabash: the art and artists of the Caribbean” 3-part lecture series, Barrows Hall, University of California at Berkeley Apr. 1999 “Time past, time present: Figuration, abstraction and the politics of race and gender”. Townsend Center for the Humanities, Stephens Hall, University of California at Berkeley Nov. 1998 “The Calabash Lecture”, Kroeber Hall, University of California at Berkeley Awards 1996 Purchase award by the 23rd Bienal of Sao Paulo 1995 Mural – Hewamorra International Airport, St. Lucia 1994 Organization of American States sponsorship to Belize 1978 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship in Painting 1977 Invited by the 2nd World festival of African Arts and Culture, Lagos, Nigeria 1976 Artists-in-Berlin Programme (Berliner Kunsler Programme des DAAD) 1973 British Council Award 1971 Brazilian Government sponsorship to the 11th Bienal of Sao Paulo, Brazil 1971 British Prix de Rome, Italy 1970 Boise Traveling Scholarship Stage Designs 1971 “Jimmy K. -

L~Uli~~(1I1I1I11I1I1I1I111I1I1I1 ' 8701561247 Thesis Abstract

/ African Caribbean Pupils and Art Education Paul Dash Goldsmiths, University of London Thesis submitted for the degree of Philosophical Doctorate September 2007 ~~L~Uli~~(1I1I1I11I1I1I1I111I1I1I1 ' 8701561247 Thesis Abstract This work looks at the implications for teaching art and design to children of African Caribbean heritage in the British educational system. It is organised in three sections. The first provides the broad rationale for the thesis and includes an analysis of viewpoints on the diasporic state, this instead of a literature review. It asserts that children of African Caribbean and wider diasporic backgrounds are disadvantaged by not being made familiar with material from their cultural heritages. This has come about, I argue, by the enduring effects of the rupture that was the slave trade and the lack of acknowledgement of the significance of the black presence in the West. Consequently, the study contends, diasporic peoples are rendered invisible. The thesis asserts that culture as a context for teaching is fundamental to art and design education. Therefore African Caribbean learners, whose cultural heritages are not seen, are disadvantaged and appear culturally impoverished relative to· others. To substantiate this critical viewpoint, key texts by theorists on diasporic studies are referenced and analysed. These include David Dabydeen, CLR James, Stuart Hall and Kamau Brathwaite. My intention in this first section, therefore, is to throw light on the tensions surrounding the black subject, their lack of a positive presence in the critical and contextual material that children are exposed to and how this tension impacts on the teaching of art. The values disseminated in such pedagogies are central to the enquiry. -

Black British Art History Some Considerations

New Directions in Black British Art History Some Considerations Eddie Chambers ime was, or at least time might have been, when the writing or assembling of black British art histories was a relatively uncom- Tplicated matter. Historically (and we are now per- haps able to speak of such a thing), the curating or creating of black British art histories were for the most part centered on correcting or addressing the systemic absences of such artists. This making vis- ible of marginalized, excluded, or not widely known histories was what characterized the first substantial attempt at chronicling a black British history: the 1989–90 exhibition The Other Story: Asian, African, and Caribbean Artists in Post-War Britain.1 Given the historical tenuousness of black artists in British art history, this endeavor was a landmark exhibi- tion, conceived and curated by Rasheed Araeen and organized by Hayward Gallery and Southbank Centre, London. Araeen also did pretty much all of the catalogue’s heavy lifting, providing its major chapters. A measure of the importance of The Other Story can be gauged if and when we consider that, Journal of Contemporary African Art • 45 • November 2019 8 • Nka DOI 10.1215/10757163-7916820 © 2019 by Nka Publications Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/nka/article-pdf/2019/45/8/710839/20190008.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 Catalogue cover for the exhibition Transforming the Crown: African, Asian, and Caribbean Artists in Britain 1966–1996, presented by the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute, New York, and shown across three venues between October 14, 1997, and March 15 1998: Studio Museum in Harlem, Bronx Museum of the Arts, and Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute. -

To Download the Contemporary Art

CONTEMPORARY ART SOCIETY Patron Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother The Annual General Meeting of the Contemporary Art Society will be held in the Lecture Theatre of the Tate Gallery on June 20, 1977 at 6.30 p.m. Executive Committee Nancy Balfour OBE Chairman Alistair McAlpine Vice Chairman AGENDA Lord Croft Honorary Treasurer Caryl Hubbard Honorary Treasurer 1. Consideration of Balance Sheet and Income and Expenditure Accounts Max Gordon Sir Norman Reid 2. Appointment of Auditors Lady Vaizey Anthony Diamond 3> Sir Norman Reid and Max Gordon retire from the Committee under Norbert Lynton Article 41. The following nomination for election to the Committee has Peter Moores been received: Edward Lucie-Smith Belle Shenkman Marquess of Dufferin and Ava Catherine Curran 4. Any other business Joanna Drew Gabrielle Keiller Bryan Montgomery Geoffrey Tucker CBE Alan Bowness CBE By order of the Committee Carol Hogben Pauline Vogelpoel MBE Organising Secretary Pauline Vogelpoel Committee Report for the year ended 31 December 1976 May 15 1977 During the year Peter Meyer and Neville Burston retired from the Committee by rotation. Nancy Balfour became Chairman, Lord Croft became Honorary Treasurer and Caryl Hubbard became Honorary Secretary. Alan Bowness, Carol Hogben, Bryan Montgomery and Geoffrey Tucker were elected to the Committee. Belle Shenkman and Anne Sutton were co-opted to the Committee. The principal activity of the Society is to acquire contemporary works of art for presentation to Public Art Collections in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth. The Society's activities during the year resulted in a deficit of £1,656. The accumulated fund amounted to £9,567 at 31 December 1976 NANCY BALFOUR Chairman May 15 1977 Chairman's Report in 1978. -

2009 Benefit Trust Or Private Foundation) Department of the Treasury •

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93493133008380 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung 2009 benefit trust or private foundation) Department of the Treasury • . Internal Revenue Service 0- The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements A For the 2009 calendar year, or tax year beginning 01 -01-2009 and ending 12 -31-2009 C Name of organization D Employer identification number B Check if applicable Please NATIONAL COUNCIL OF YMCAs OF THE USA F Address change use IRS 36-3258696 label or Doing Business As E Telephone number F Name change print or YMCA OF THE USA type . See (312 ) 977-0031 1 Initial return Specific N um b er and st reet (or P 0 box if mai l is not d e l ivered to st ree t a dd ress ) R oom/suite Instruc - 101 NORTH WACKER DRIVE G Gross receipts $ 82,344,519 F_ Terminated tions . F-Amended return City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 CHICAGO, IL 60606 F_ Application pending F Name and address of principal officer H(a) Is this a group return for NEILI NICOLL affiliates? fl Yes F No 101 NORTH WACKER DRIVE CHICAGO,IL 60606 H(b) Are all affiliates included ? fl Yes F_ No If"No," attach a list (see instructions) I Tax - exempt status F 501( c) ( 3 I (insert no ) 1 4947(a)(1) or F_ 527 H(c) Group exemption number 0- 3 Website : - www ymca net K Form of organization F Corporation 1 Trust F_ Association 1 Other 1- L Year of formation 1982 M State of legal domicile IL urnmar y 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities YMCA OFTHE USA (Y-USA) IS THE NATIONAL RESOURCE OFFICE FOR THE NATION'S 2,687 YMCAS, WHICH NURTURE THE POTENTIAL OF KIDS, PROMOTE HEALTHY LIVING FOR ALL AND FOSTER SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 2 Check this box Of- if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets 3 N umber of voting members of the governing body (Part VI, line la) . -

Objective of the Institute Was Felt That the Objectives of the Insti¬ to Achieve a More Seasoned View of Rights for L Nion Members" by Mr

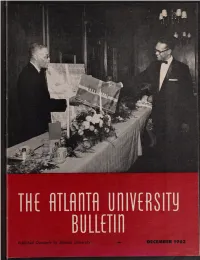

DaLL of (Contents Page Calendar 3 Dr. Clement Honored .......... 4 & 5 6 Appreciation .... Profile . 7 Charter Day Observed 8 The Summer Commencement 11 Slimmer School Activities 13 Campus Briefs 15 Faculty Items 22 Alumni News 25 In Memoriam _ __ .. - _ 31 • ON THE COVER • * President Rufus E. Clement receiving gifts from the Faculty and Staff in appre¬ ciation for his twenty-five years of loyal service as President of Atlanta University. Dr. Thomas D. Jarrett made the presenta¬ tion at the Annual Charter Day Banquet. * Series III DECEMBER, 1962 No. 118 Second Class Postage paid at Atlanta, Georgia 2 Atlanta University Bulletin CALENDAR SUMMER SCHOOL FORUM: June 19 — Mayor Ivan LECTURE: October 4 —Mrs. Aleanor Merrifield, Allen. Jr., “Urbanization: Problems and Chal¬ University of Illinois, “Experimental Programs for lenges.” Field Instruction of Social Work Students." TEA: October 7 — Atlanta BOOK REVIEW PROGRAM: June 20 — The Rich Na¬ University Alumni Associ¬ ation at Home to tions and the Poor Nations by Barbara Ward — Students, Faculty and Staff. Reviewed by President Rufus E. Clement. CHARTER DAY CONVOCATION: October 16 — Judge SUMMER THEATRE: June 21. 22, 23 — “Six Who Sidney A. Jones, Jr., Judge of the Municipal Court Pass While the Lentils Boil” by Stuart Walker. of Chicago. CHARTER DAY — SUMMER SCHOOL FORUM: June 26 — Dr. Asa G. BANQUET: October 16 Honoring New Members of the Facultv and Staff. ’i ancey, Head of the Department of Surgery, Hughes Spalding Pavilion. “Modern Man and Medi¬ NONWESTERN STUDIES LECTURE: October 24 — cine.” Dr. Bernard S. Cohn, University of Rochester. “Indian Society: Unity in Diversity.” SUMMER SCHOOL FORUM: July 3 — Dr. -

An Online Art Magazine Print Edition No. 2 Unter Den Linden 13/15 10117 Berlin Daily 10 Am – 8 Pm Mondays Admission Free Deutsche-Bank-Kunsthalle.Com

p.3 A New Home for PULL-OUT SPECIAL: Contemporary Art from African Perspectives p.15 Johannesburg, Cairo, Dar A South African property es Salaam, London, Rabat company has teamed up with A glance inside libraries a German collector to open and book collections holding Africa’s first mega-museum rare and often forgotten publications p.6 The Black Cultural Archives The opening of the Archive’s p.27 Letter from Nairobi purpose-built space in London Donald Kuira Maingi on coincides with the arrival of diverse forms of contemporary the book Black Artists in British performance practice Art: A History since the 1950s by Eddie Chambers FOCUS KAMPALA: p.10 Symbols of a Cultural p.28 KLA ART puts East African Golden Age Art on the Map Remembering four ground- How a contemporary art breaking African festivals festival in Kampala has grown and developed p.12 Digital Art A closer look at leading-edge p.30 New Curators on the Block organizations, platforms, and A conversation with the young artists championing team behind this year’s digital art and technologies KLA ART Festival p.14 Interview with p.32 Interview with Emma Emeka Udemba Wolukau-Wanambwa Artist and initiator of the Artist and researcher working Molue Mobile Museum of on representations of late Contemporary Art in Lagos colonialism in East Africa p.36 Transition: A Review tested by Post-Colonial Africa How one magazine shaped the editorial landscape of an entire continent Nkiruka Oparah, Oparah, Nkiruka (courtesy of the artist) Precursor to a New Dream , 2014 2014 , COntempOrarYand.COM An online art magazine Print edition no. -

Cold Islanders

Cold Islanders Moana Pasifika/Oceania identified artists creating and occupying respectful stances of strength and confidence in Aotearoa Olga H J Wilson A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (MPhil) Te Ara Poutama Auckland University of Technology 2020 Chief Supervisor: Emeritus Professor Ngahuia Te Awekotuku Secondary Supervisor: Professor Waimarie Linda Nikora 1 Lotu - Karakia Creator God May those needing to find safe waters be comforted by the words that spring from your Source. In the deep dark waters may they find you And in the ninth heavens may they find you And in primordial time and space May they find themselves. Three Oceans around the Vā, Te Whenua and Le Fanua Guide us to a spacious place upon which to stand. 2 Table of Contents Karakia……………………………………………………………………………………….………..2 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….…….…6 List of Figures …………………………………………………………………………………………7 List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………………….…..9 List of Appendices.……………………………………………………………….…………………..10 List of Abbreviations, Terminologies…………………………………………….……………….......11 Glossary…………………………………………………………………………………………….…12 Attestation of Authorship………………………………………………………………………..........15 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………...16 Chapter 1: Introduction ………………………………………………………………………..…...18 Research Purpose …………………………………………………………………………………......18 Research Questions…………………………………………………………………………………...19 Looking Back to Move Forward………………………………………………………………….......19 -

To Download the Contemporary Art Society Report 1971-72 (Pdf)

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother Although this meeting will be approving the accounts for the calendar year 1971, I am, as Is customary, reporting on the events of the last twelve months. This has been an eventful period for the Society, so that for once the details of our parties and jollifications will have to take second place. Whitney Straight CBE MC DFC Chairman Whatever our views may be on the Government's decision to introduce museum Anthony Lousada Vice Chairman charges, we were delighted to learn that our members wouid be exempt, Peter Meyer Honorary Treasurer provided that their annua! subscription was at least £3. When considering raising The Hon J D Sainsbury Honorary Secretary the subscription to this level, we decided that we should take the positive steps to encourage the signature of Deeds of Covenant and Bankers Orders. As ! have so often said in my reports as Honorary Treasurer, a Deed of Covenant entities us to reclaim income tax on the subscription and a Bankers Order saves us a great Peter Meyer Chairman deal of administrative work. For these reasons we fixed the subscription at £4, The Hon J D Sainsbury Vice Chairman with a reduction to £3 if both a Deed and an Order were completed. We did this Nancy Balfour OBE Honorary Treasurer with some apprehension, but ! am delighted to say that it has been extremely Lord Croft Honorary Secretary well received. Bryan Robertson Sir Norman Reid You may be concerned at the fact that the introduction of museum charges, David Thompson originally fixed for the 1st January, has been postponed, but I understand they Alistair McAlpine will indeed start later this year.