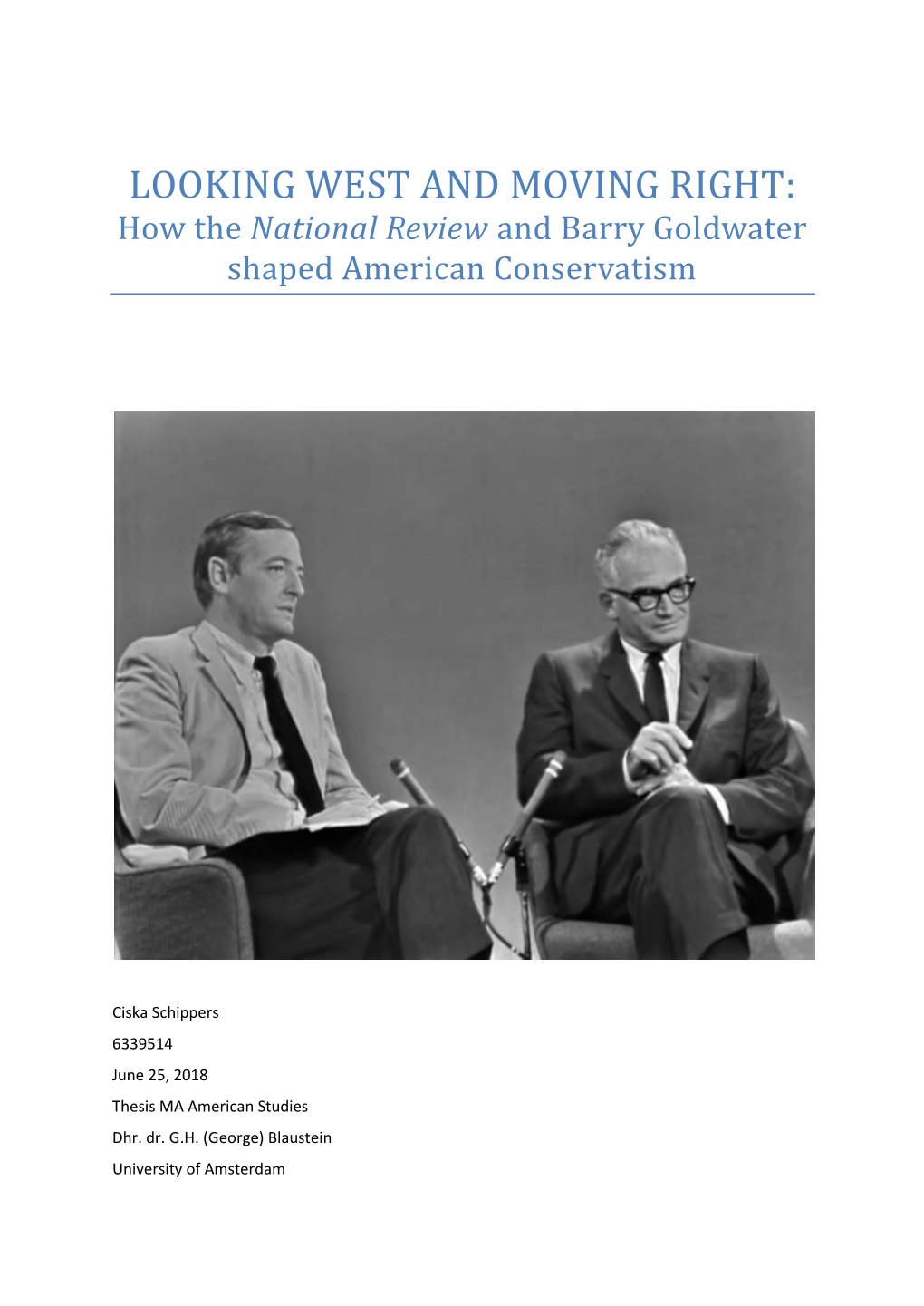

National Review and Barry Goldwater Shaped American Conservatism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 the Right-Wing Media Enablers of Anti-Islam Propaganda

Chapter 4 The right-wing media enablers of anti-Islam propaganda Spreading anti-Muslim hate in America depends on a well-developed right-wing media echo chamber to amplify a few marginal voices. The think tank misinforma- tion experts and grassroots and religious-right organizations profiled in this report boast a symbiotic relationship with a loosely aligned, ideologically-akin group of right-wing blogs, magazines, radio stations, newspapers, and television news shows to spread their anti-Islam messages and myths. The media outlets, in turn, give members of this network the exposure needed to amplify their message, reach larger audiences, drive fundraising numbers, and grow their membership base. Some well-established conservative media outlets are a key part of this echo cham- ber, mixing coverage of alarmist threats posed by the mere existence of Muslims in America with other news stories. Chief among the media partners are the Fox News empire,1 the influential conservative magazine National Review and its website,2 a host of right-wing radio hosts, The Washington Times newspaper and website,3 and the Christian Broadcasting Network and website.4 They tout Frank Gaffney, David Yerushalmi, Daniel Pipes, Robert Spencer, Steven Emerson, and others as experts, and invite supposedly moderate Muslim and Arabs to endorse bigoted views. In so doing, these media organizations amplify harm- ful, anti-Muslim views to wide audiences. (See box on page 86) In this chapter we profile some of the right-wing media enablers, beginning with the websites, then hate radio, then the television outlets. The websites A network of right-wing websites and blogs are frequently the primary movers of anti-Muslim messages and myths. -

Periodicalspov.Pdf

“Consider the Source” A Resource Guide to Liberal, Conservative and Nonpartisan Periodicals 30 East Lake Street ∙ Chicago, IL 60601 HWC Library – Room 501 312.553.5760 ver heard the saying “consider the source” in response to something that was questioned? Well, the same advice applies to what you read – consider the source. When conducting research, bear in mind that periodicals (journals, magazines, newspapers) may have varying points-of-view, biases, and/or E political leanings. Here are some questions to ask when considering using a periodical source: Is there a bias in the publication or is it non-partisan? Who is the sponsor (publisher or benefactor) of the publication? What is the agenda of the sponsor – to simply share information or to influence social or political change? Some publications have specific political perspectives and outright state what they are, as in Dissent Magazine (self-described as “a magazine of the left”) or National Review’s boost of, “we give you the right view and back it up.” Still, there are other publications that do not clearly state their political leanings; but over time have been deemed as left- or right-leaning based on such factors as the points- of-view of their opinion columnists, the make-up of their editorial staff, and/or their endorsements of politicians. Many newspapers fall into this rather opaque category. A good rule of thumb to use in determining whether a publication is liberal or conservative has been provided by Media Research Center’s L. Brent Bozell III: “if the paper never met a conservative cause it didn’t like, it’s conservative, and if it never met a liberal cause it didn’t like, it’s liberal.” Outlined in the following pages is an annotated listing of publications that have been categorized as conservative, liberal, non-partisan and religious. -

Juliana Geran Pilon Education

JULIANA GERAN PILON [email protected] Dr. Juliana Geran Pilon is Research Professor of Politics and Culture and Earhart Fellow at the Institute of World Politics. For the previous two years, she taught in the Political Science Department at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. From January 1991 to October 2002, she was first Director of Programs, Vice President for Programs, and finally Senior Advisor for Civil Society at the International Foundation for Election Systems (IFES), after three years at the National Forum Foundation, a non-profit institution that focused on foreign policy issues - now part of Freedom House - where she was first Executive Director and then Vice President. At NFF, she assisted in creating a network of several hundred young political activists in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. For the past thirteen years she has also taught at Johns Hopkins University, the Institute of World Politics, George Washington University, and the Institute of World Politics. From 1981 to 1988, she was a Senior Policy Analyst at the Heritage Foundation, writing on the United Nations, Soviet active measures, terrorism, East-West trade, and other international issues. In 1991, she received an Earhart Foundation fellowship for her second book, The Bloody Flag: Post-Communist Nationalism in Eastern Europe -- Spotlight on Romania, published by Transaction, Rutgers University Press. Her autobiographical book Notes From the Other Side of Night was published by Regnery/Gateway, Inc. in 1979, and translated into Romanian in 1993, where it was published by Editura de Vest. A paperback edition appeared in the U.S. in May 1994, published by the University Press of America. -

By Philip Roth

The Best of the 60s Articles March 1961 Writing American Fiction Philip Roth December 1961 Eichmann’s Victims and the Unheard Testimony Elie Weisel September 1961 Is New York City Ungovernable? Nathan Glazer May 1962 Yiddish: Past, Present, and Perfect By Lucy S. Dawidowicz August 1962 Edmund Wilson’s Civil War By Robert Penn Warren January 1963 Jewish & Other Nationalisms By H.R. Trevor-Roper February 1963 My Negro Problem—and Ours By Norman Podhoretz August 1964 The Civil Rights Act of 1964 By Alexander M. Bickel October 1964 On Becoming a Writer By Ralph Ellison November 1964 ‘I’m Sorry, Dear’ By Leslie H. Farber August 1965 American Catholicism after the Council By Michael Novak March 1966 Modes and Mutations: Quick Comments on the Modern American Novel By Norman Mailer May 1966 Young in the Thirties By Lionel Trilling November 1966 Koufax the Incomparable By Mordecai Richler June 1967 Jerusalem and Athens: Some Introductory Reflections By Leo Strauss November 1967 The American Left & Israel By Martin Peretz August 1968 Jewish Faith and the Holocaust: A Fragment By Emil L. Fackenheim October 1968 The New York Intellectuals: A Chronicle & a Critique By Irving Howe March 1961 Writing American Fiction By Philip Roth EVERAL winters back, while I was living in Chicago, the city was shocked and mystified by the death of two teenage girls. So far as I know the popu- lace is mystified still; as for the shock, Chicago is Chicago, and one week’s dismemberment fades into the next’s. The victims this particular year were sisters. They went off one December night to see an Elvis Presley movie, for the sixth or seventh time we are told, and never came home. -

INTERNSHIP RESOURCES and HELPFUL SEARCH LINKS These Sites Allow You to Do Advanced Searches for Internships Nationwide

CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE OFFICE OF CAREER & LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT 2017 INTERNSHIP LIST New Jobs…………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Politics/Non-profit…………………………………………………………………... 3 Public Policy/Non-profit …………………………………………………………... 5 Business……………………………………………………………………………... 10 Journalism and Media ……………………………………………………………… 11 Catholic/Pro-Life/Religious Freedom ……………………………………………… 13 Academic/Student Conferences and Fellowships ………………………………….. 14 Other ………………………………………………………………………………... 15 Internship Resources and Search Links …………………………………………….. 16 Please note: this is not meant to be exhaustive list, nor are all internships endorsed by Christendom College or the Office of Career Development. Many of the internships below are in the Metropolitan DC area, but there are thousands of internships available around the country. Use the resources on pg. 16 to do a search by field and location. Questions? Need help with your resume, cover letter, or composing an email? Contact Colleen Harmon: [email protected] ** Indicates alumni have or currently do work at this location. If you plan to apply to these internships, please let Colleen know so she can notify them. 1 NEW JOBS! National Journalism Center- summer deadline March 20 The National Journalism Center, a project of Young America's Foundation, provides aspiring conservative and libertarian journalists with the premier opportunity to learn the principles and practice of responsible reporting. The National Journalism Center combines 12 weeks of on-the- job training at a Washington, D.C.-based media outlet and once-weekly training seminars led by prominent journalists, policy experts, and NJC faculty. The program matches interns with print, broadcast, or online media outlets based on their interests and experience. Interns spend 30 hours/week gaining practical, hands-on journalism experience. Potential placements include The Washington Times, The Washington Examiner, CNN, Fox News Channel, and more. -

Conservative Movement

Conservative Movement How did the conservative movement, routed in Barry Goldwater's catastrophic defeat to Lyndon Johnson in the 1964 presidential campaign, return to elect its champion Ronald Reagan just 16 years later? What at first looks like the political comeback of the century becomes, on closer examination, the product of a particular political moment that united an unstable coalition. In the liberal press, conservatives are often portrayed as a monolithic Right Wing. Close up, conservatives are as varied as their counterparts on the Left. Indeed, the circumstances of the late 1980s -- the demise of the Soviet Union, Reagan's legacy, the George H. W. Bush administration -- frayed the coalition of traditional conservatives, libertarian advocates of laissez-faire economics, and Cold War anti- communists first knitted together in the 1950s by William F. Buckley Jr. and the staff of the National Review. The Reagan coalition added to the conservative mix two rather incongruous groups: the religious right, primarily provincial white Protestant fundamentalists and evangelicals from the Sunbelt (defecting from the Democrats since the George Wallace's 1968 presidential campaign); and the neoconservatives, centered in New York and led predominantly by cosmopolitan, secular Jewish intellectuals. Goldwater's campaign in 1964 brought conservatives together for their first national electoral effort since Taft lost the Republican nomination to Eisenhower in 1952. Conservatives shared a distaste for Eisenhower's "modern Republicanism" that largely accepted the welfare state developed by Roosevelt's New Deal and Truman's Fair Deal. Undeterred by Goldwater's defeat, conservative activists regrouped and began developing institutions for the long haul. -

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980 Robert L. Richardson, Jr. A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by, Michael H. Hunt, Chair Richard Kohn Timothy McKeown Nancy Mitchell Roger Lotchin Abstract Robert L. Richardson, Jr. Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1985 (Under the direction of Michael H. Hunt) This dissertation examines the origins and evolution of neoconservatism as a philosophical and political movement in America from 1945 to 1980. I maintain that as the exigencies and anxieties of the Cold War fostered new intellectual and professional connections between academia, government and business, three disparate intellectual currents were brought into contact: the German philosophical tradition of anti-modernism, the strategic-analytical tradition associated with the RAND Corporation, and the early Cold War anti-Communist tradition identified with figures such as Reinhold Niebuhr. Driven by similar aims and concerns, these three intellectual currents eventually coalesced into neoconservatism. As a political movement, neoconservatism sought, from the 1950s on, to re-orient American policy away from containment and coexistence and toward confrontation and rollback through activism in academia, bureaucratic and electoral politics. Although the neoconservatives were only partially successful in promoting their transformative project, their accomplishments are historically significant. More specifically, they managed to interject their views and ideas into American political and strategic thought, discredit détente and arms control, and shift U.S. foreign policy toward a more confrontational stance vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. -

CPAC: the Origins and Role of the Conference in the Expansion and Consolidation of the Conservative Movement, 1974-1980

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 CPAC: The Origins and Role of The Conference in the Expansion and Consolidation of the Conservative Movement, 1974-1980 Daniel Preston Parker University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Daniel Preston, "CPAC: The Origins and Role of The Conference in the Expansion and Consolidation of the Conservative Movement, 1974-1980" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1113. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1113 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1113 For more information, please contact [email protected]. CPAC: The Origins and Role of The Conference in the Expansion and Consolidation of the Conservative Movement, 1974-1980 Abstract The Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) is an annual event that brings conservative politicians, public intellectuals, pundits, and issue activists together in Washington, DC to discuss strategies for achieving their goals through the electoral and policy process. Although CPAC receives a great deal of attention each year from conservative movement activists and the news outlets that cover it, it has attracted less attention from scholars. This dissertation seeks to address the gap in existing knowledge by providing a fresh account of the role that CPAC played in the expansion and consolidation of the conservative movement during the 1970s. Audio recordings of the exchanges that took place at CPAC meetings held between 1974 and 1980 are transcribed and analyzed. The results of this analysis show that during the 1970s, CPAC served as an important forum where previously fragmented single issue groups and leaders of the Old Right and New Right coalitions were able to meet, share ideas, and coordinate their efforts. -

The New Betrayal

lie PEOPLE'S FRONT THE NEW BETRAYAL By JAMES BURNHAM 15 cents PIONEER PUBLISHERS 1OO FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK Th<> PEOPLE'S FRONT THE NEW BETRAYAL By JAMES BURNHAM 15 cents PIONEEK PUBLISHERS 100 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK The Peoples' Front: The New Betrayal by James Burnham 35 PIONEER PUBLISHERS • NEW YORK COPYRIGHT, 1937 PIONEER PUBLISHERS 100 FIFTH AVENUE NEW YORK, N. Y. 1)85 Printed in the United States of America Contents Page 1. ORIGIN AND THEORY OF THE PEOPLES' FRONT 2. ANALYSIS OF THE THEORY OF THE PEOPLES' FRONT 11 3 y HISTORY AND THE PEOPLES' FRONT 11 4. CAN THE PEOPLES' FRONT WIN THE MIDDLE CLASSES? 26 5. CAN THE PEOPLES' FRONT STOP FASCISM? 32 6. THE PEOPLES' FRONT IN FRANCE 39 7. THE PEOPLES' FRONT IN SPAIN 47 8. THE PEOPLES' FRONT IN THE UNITED STATES 53 9. THE REAL MEANING OF THE PEOPLES' FRONT 60 CONCISE! COMPREHENSIVE! CHALLENGING! A network of 100 alert correspondents in key cities of the U. 8. and Europe Gets first hand news from every front for the SOCIALIST CALL 21 EAST 17 ST., NEW YORK CITY REGULAR CONTRIBUTORS Norman Thomas B. J. Widick Aaron Levenstein McAlister Coleman Frank N. Trager Frank McAllister Herbert Zam John Newton Thurber Jack Altman Bruno Fischer Roy E. Burt Gus Tyler AND AN IMPOSING ARRAY OF FEATURE WRITERS SUBSCRIBE NOW! $1.00 for 6 mos. $1.50 for 1 yr. american socialist monthly 21 E. 17 St., N.Y.C. OFFICIAL THEORETICAL ORGAN OF THE SOCIALIST PARTY Vigorously represents the interests of Revolutionary Socialism STIMULATING ANALYTICAL PROVOCATIVE $1.50 a year Special Rates for Bundle Orders 15c a copy A journal devoted to a Marxian analysis of the most important problems facing the American and international Socialist movement today, by outstanding writers. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

Restoring the Balance of Powers

“The Founders intentionally placed the power of the government in the hands of the people via their representation in Congress. Yet for many years, Congress has slowly ceded its authority to the executive branch. Rather than taking the time to properly legislate, Congress has passed bills that lack detail and provide gross regulatory authority to unelected federal bureaucrats. Congress seems keen to participate in opaque rulemaking processes, begging bureaucrats to implement policies that align with congressional intent. We’ve seen the effects of this trend in every policy area, from immigration to environmental policies, and health care to foreign aid. It’s time for change. “One of the core tenants of my office mission is to restore the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches to more closely resemble what the Founders intended. I am grateful to FreedomWorks for raising awareness of this need and for the work they do reduce the size of government and promote individual liberty.” Congressman Andy Biggs (AZ-05) “The idea that the federal government is composed of three coequal branches is false. While it is essential that the three branches hold each other accountable, Congress was always intended to be the most powerful for a simple reason: it is the branch that is closest to the people, and is the only branch organized to encourage debate and compromise on the most pressing issues facing America. The founders of this great nation never imagined that Members of Congress would so willingly give away their power and responsibility, but that is exactly what we have done for a century. -

Part V Jfk- Media Image and Legacy

PART V JFK- MEDIA IMAGE AND LEGACY 242 Chapter 20 Kennedy’s Loyal Opposition: National Review and the Development of a Conservative Alternative, January- August 1961 Laura Jane Gifford The March 25, 1961, National Review related the contents of a recent subscriber letter in a back-cover subscription appeal. This man, “usually understood to be a liberal” and well-placed in New York Democratic circles, wrote the magazine and explained: Of course I am not in agreement with most of your criticism of President Kennedy; nor do I believe you will get far in your obvious editorial support of Senator Barry Goldwater, but renew my subscription, for I can no longer get along without National Review. I find that National Review is a whiskey I must sample once a week. From every other journalist I get a sensation of either soda pop (and who does not finally gag on effervescent, treacly sugar water), or from the intellectual journals of my own persuasion I now get no more than strained vegetable juices unfermented. So I am now a tippler. Eight dollars enclosed. The advertisement’s writer went on to speculate that perhaps National Review’s rarified appeal stemmed from its very lack of broadmindedness; rather, “it is a magazine of fact and opinion, of discourse and criticism, on the central questions of our age,” questions identified as dealing with how to meet the Communist challenge, “resuscitate the spirit in an age of horror,” guard one’s mind against uniformity in the age of mass appeal, and resist collectivism, preserve freedom and teach love of country, respect for past wisdom and responsibility to the future.