Part V Jfk- Media Image and Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 the Right-Wing Media Enablers of Anti-Islam Propaganda

Chapter 4 The right-wing media enablers of anti-Islam propaganda Spreading anti-Muslim hate in America depends on a well-developed right-wing media echo chamber to amplify a few marginal voices. The think tank misinforma- tion experts and grassroots and religious-right organizations profiled in this report boast a symbiotic relationship with a loosely aligned, ideologically-akin group of right-wing blogs, magazines, radio stations, newspapers, and television news shows to spread their anti-Islam messages and myths. The media outlets, in turn, give members of this network the exposure needed to amplify their message, reach larger audiences, drive fundraising numbers, and grow their membership base. Some well-established conservative media outlets are a key part of this echo cham- ber, mixing coverage of alarmist threats posed by the mere existence of Muslims in America with other news stories. Chief among the media partners are the Fox News empire,1 the influential conservative magazine National Review and its website,2 a host of right-wing radio hosts, The Washington Times newspaper and website,3 and the Christian Broadcasting Network and website.4 They tout Frank Gaffney, David Yerushalmi, Daniel Pipes, Robert Spencer, Steven Emerson, and others as experts, and invite supposedly moderate Muslim and Arabs to endorse bigoted views. In so doing, these media organizations amplify harm- ful, anti-Muslim views to wide audiences. (See box on page 86) In this chapter we profile some of the right-wing media enablers, beginning with the websites, then hate radio, then the television outlets. The websites A network of right-wing websites and blogs are frequently the primary movers of anti-Muslim messages and myths. -

Periodicalspov.Pdf

“Consider the Source” A Resource Guide to Liberal, Conservative and Nonpartisan Periodicals 30 East Lake Street ∙ Chicago, IL 60601 HWC Library – Room 501 312.553.5760 ver heard the saying “consider the source” in response to something that was questioned? Well, the same advice applies to what you read – consider the source. When conducting research, bear in mind that periodicals (journals, magazines, newspapers) may have varying points-of-view, biases, and/or E political leanings. Here are some questions to ask when considering using a periodical source: Is there a bias in the publication or is it non-partisan? Who is the sponsor (publisher or benefactor) of the publication? What is the agenda of the sponsor – to simply share information or to influence social or political change? Some publications have specific political perspectives and outright state what they are, as in Dissent Magazine (self-described as “a magazine of the left”) or National Review’s boost of, “we give you the right view and back it up.” Still, there are other publications that do not clearly state their political leanings; but over time have been deemed as left- or right-leaning based on such factors as the points- of-view of their opinion columnists, the make-up of their editorial staff, and/or their endorsements of politicians. Many newspapers fall into this rather opaque category. A good rule of thumb to use in determining whether a publication is liberal or conservative has been provided by Media Research Center’s L. Brent Bozell III: “if the paper never met a conservative cause it didn’t like, it’s conservative, and if it never met a liberal cause it didn’t like, it’s liberal.” Outlined in the following pages is an annotated listing of publications that have been categorized as conservative, liberal, non-partisan and religious. -

The Roots of Conservative Victory in the 1960S

Rick Perlstein Thunder on the Right: The Roots of Conservative Victory in the 1960s Downloaded from our scenes from the spring and summer of 1963: In Florissant, In Rogers, Indiana, clamoring members of the conservative activist Missouri, not far outside St. Louis, 500 protesters hold up a group Young Americans for Freedom hurl wicker baskets into a raging Fforest of picket signs and chant angry slogans: another disruptive bonfi re. “Rogers Defends Liberty,” read their signs. The baskets, they Sixties protest. The state legislature has refused the activists’ demands say, have been manufactured behind the Iron Curtain. concerning the local schools, and the activists have responded by trying Finally, in a massive Washington, D.C., armory, on a sweltering to shut the schools down. They July 4th, an event that sought http://maghis.oxfordjournals.org/ are demonstrating for busing. to focus the political energies Only none of the demonstrators behind all these disparate are black. They are parents of phenomena towards a single children in Catholic schools, political goal. The only time it had and the legislature, citing the been fi lled to capacity before was First Amendment’s proscription for the Eisenhower and Kennedy against the mixing of church and inaugural balls and a Billy Graham state, has refused their request for crusade. Now it was packed for a the same bus service that public rally to draft Barry Goldwater for school families receive. They sing president. It resembled a national at CUNY Graduate Center on September 27, 2012 the same “freedom songs” they political convention, right down have recently heard Martin Luther to the brass band, fl ags, costumes, King’s demonstrators sing in and screaming throngs, though Birmingham, Alabama. -

Juliana Geran Pilon Education

JULIANA GERAN PILON [email protected] Dr. Juliana Geran Pilon is Research Professor of Politics and Culture and Earhart Fellow at the Institute of World Politics. For the previous two years, she taught in the Political Science Department at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. From January 1991 to October 2002, she was first Director of Programs, Vice President for Programs, and finally Senior Advisor for Civil Society at the International Foundation for Election Systems (IFES), after three years at the National Forum Foundation, a non-profit institution that focused on foreign policy issues - now part of Freedom House - where she was first Executive Director and then Vice President. At NFF, she assisted in creating a network of several hundred young political activists in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. For the past thirteen years she has also taught at Johns Hopkins University, the Institute of World Politics, George Washington University, and the Institute of World Politics. From 1981 to 1988, she was a Senior Policy Analyst at the Heritage Foundation, writing on the United Nations, Soviet active measures, terrorism, East-West trade, and other international issues. In 1991, she received an Earhart Foundation fellowship for her second book, The Bloody Flag: Post-Communist Nationalism in Eastern Europe -- Spotlight on Romania, published by Transaction, Rutgers University Press. Her autobiographical book Notes From the Other Side of Night was published by Regnery/Gateway, Inc. in 1979, and translated into Romanian in 1993, where it was published by Editura de Vest. A paperback edition appeared in the U.S. in May 1994, published by the University Press of America. -

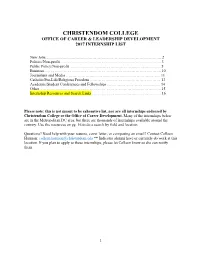

INTERNSHIP RESOURCES and HELPFUL SEARCH LINKS These Sites Allow You to Do Advanced Searches for Internships Nationwide

CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE OFFICE OF CAREER & LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT 2017 INTERNSHIP LIST New Jobs…………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Politics/Non-profit…………………………………………………………………... 3 Public Policy/Non-profit …………………………………………………………... 5 Business……………………………………………………………………………... 10 Journalism and Media ……………………………………………………………… 11 Catholic/Pro-Life/Religious Freedom ……………………………………………… 13 Academic/Student Conferences and Fellowships ………………………………….. 14 Other ………………………………………………………………………………... 15 Internship Resources and Search Links …………………………………………….. 16 Please note: this is not meant to be exhaustive list, nor are all internships endorsed by Christendom College or the Office of Career Development. Many of the internships below are in the Metropolitan DC area, but there are thousands of internships available around the country. Use the resources on pg. 16 to do a search by field and location. Questions? Need help with your resume, cover letter, or composing an email? Contact Colleen Harmon: [email protected] ** Indicates alumni have or currently do work at this location. If you plan to apply to these internships, please let Colleen know so she can notify them. 1 NEW JOBS! National Journalism Center- summer deadline March 20 The National Journalism Center, a project of Young America's Foundation, provides aspiring conservative and libertarian journalists with the premier opportunity to learn the principles and practice of responsible reporting. The National Journalism Center combines 12 weeks of on-the- job training at a Washington, D.C.-based media outlet and once-weekly training seminars led by prominent journalists, policy experts, and NJC faculty. The program matches interns with print, broadcast, or online media outlets based on their interests and experience. Interns spend 30 hours/week gaining practical, hands-on journalism experience. Potential placements include The Washington Times, The Washington Examiner, CNN, Fox News Channel, and more. -

Conservatives on Madison Avenue: Political Advertising and Direct Marketing in the 1950S

NANZAN REVIEW OF AMERICAN STUDIES Volume 41 (2019): 3-25 Conservatives on Madison Avenue: Political Advertising and Direct Marketing in the 1950s MORIYAMA Takahito * This article investigates how urban consumerism affected the rise of modern American conservatism by focusing on anticommunists’ political advertising in New York City during the 1950s. The advertising industry developed the new tactic of direct marketing in the post-World War II period and, over the years, several political activists adopted this new marketing technique for political campaigns. Direct mail, a product of the new marketing, was a personalized medium that built up a database of personal information and sent suitable messages to individuals, instead of standardized information to the masses. The medium was especially significant for conservatives to disseminate their ideology to prospective supporters across the country in the 1950s when the conservati ve media establishment did not exist. This research explores the development of the American right in urban areas by analyzing the role of direct mail in the conservative movement. The postwar era witnessed the rise of modern American conservatism as a political movement. Following World War II, anticommunism became widespread among Americans and the United States was confronted with communism abroad, whereas in domestic politics right-wing movements, such as McCarthyism, attacked liberalism. The New Deal had angered many Americans prior to the 1950s. Frustrated with government regulations since the 1930s, some businesspeople acclaimed the free enterprise system and individual liberties as the American ideal; several intellectuals and religious figures criticized the decline of traditional values in modern society; and white Southerners were adamant in preventing the federal government from interfering in the Jim Crow laws. -

Chapter One: Postwar Resentment and the Invention of Middle America 10

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________ Timothy Melley, Director ________________________________________ C. Barry Chabot, Reader ________________________________________ Whitney Womack Smith, Reader ________________________________________ Marguerite S. Shaffer, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT TALES FROM THE SILENT MAJORITY: CONSERVATIVE POPULISM AND THE INVENTION OF MIDDLE AMERICA by Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff In this dissertation I show how the conservative movement lured the white working class out of the Democratic New Deal Coalition and into the Republican Majority. I argue that this political transformation was accomplished in part by what I call the "invention" of Middle America. Using such cultural representations as mainstream print media, literature, and film, conservatives successfully exploited what came to be known as the Social Issue and constructed "Liberalism" as effeminate, impractical, and elitist. Chapter One charts the rise of conservative populism and Middle America against the backdrop of 1960s social upheaval. I stress the importance of backlash and resentment to Richard Nixon's ascendancy to the Presidency, describe strategies employed by the conservative movement to win majority status for the GOP, and explore the conflict between this goal and the will to ideological purity. In Chapter Two I read Rabbit Redux as John Updike's attempt to model the racial education of a conservative Middle American, Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom, in "teach-in" scenes that reflect the conflict between the social conservative and Eastern Liberal within the author's psyche. I conclude that this conflict undermines the project and, despite laudable intentions, Updike perpetuates caricatures of the Left and hastens Middle America's rejection of Liberalism. -

On the Hill with the College's First Congresswoman, Kirsten Gillibrand '88

HOUSE TOUR ON THE HILL WITH THE COLLEGE'S FIRST CONGRESSWOMAN, KIRSTEN GILLIBRAND '88 FIVE DOLLARS Nov/Dec 2007 06-7dam.qxd:06-7dam 10/7/07 11:31 PM Page 7 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2007 Change Agent Al Dotson ’82, president of 100 Black Men of America Inc. Contents Page 54 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 10 LETTERS Climbing the Hill Notebook 44 22 CAMPUS News and notes from around the Green. Becoming Dartmouth’s first congresswoman re- 26 INTERVIEW Trustee board chair Ed Haldeman ’70 talks about quired an election upset for Kirsten Gillibrand ’88. board expansion, apathetic alums and The Wall Street Journal. Winning reelection may be even harder. 28 ONLINE An unassuming student transforms his blog into a force By Dirk Olin ’81 to be reckoned with. By Jake Tapper ’91 32 SPORTS Big Green aquatic teams may have survived extinction five years ago, but they’re still feeling the effects of the financial fiasco. 50 Drug Buster By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 As society softens its take on marijuana, Dr. 34 ALUMNI OPINION How to win—without weapons—in Herbert Kleber ’56 knows better. The psychiatrist’s Afghanistan. By Nathaniel Fick ’99 research shows the harmful effects of pot and other 36 PERSONAL HISTORY A teacher finds an appreciation of the clas- drugs on the brain—and offers hope for breaking sics in an unlikely place: a ninth grade classroom in Brooklyn. the lock of addiction. By Alexander Nazaryan ’02 By Christopher S. Wren ’57 38 TRIBUTE The late Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy made an indelible impression. By Jeffrey Hart ’51 42 READWORTHY Students reflect on their ethnicity 54 The Role Model in two new collections of essays. -

Conservatism and the Quest for Community

Conservatism and the Quest for Community William Schambra he age of obama has been an age of revival for the Progressive Tideal of a “national community.” It is a vision rooted in two core beliefs: that direct, local associations and channels of action are too often overwhelmed by the differences among communities and the fractious character of American public life; and that rather than strengthening the sources of these differences, modern government should seek to overcome them in the service of a coherent national ambition. By dis- tributing the same benefits, protections, and services to all Americans, fellow feeling and neighborliness can be fostered among the public; combined with the power of the national government and professional expertise, this communal sentiment can then become a valuable weapon for attacking America’s most pressing social problems. A century ago, this ideal was a central tenet of the Progressive agenda — which sought, as Progressive icon Herbert Croly put it in 1909, the “subordination of the individual to the demand of a dominant and constructive national purpose.” It was an important goal of the New Deal, which President Franklin Roosevelt described in 1933 as “extending to our national life the old principle of the local community.” It was the essence of the liberal agenda of the 1960s, which President Lyndon Johnson called an effort to “turn unity of interest into unity of purpose, and unity of goals into unity in the Great Society.” And it was at the core of Barack Obama’s campaign for the presidency in 2008, which promised to over- come petty differences and, as Obama put it in one campaign speech, to Wil l i a m Sch a m br a is the director of the Hudson Institute’s Bradley Center for Philanthropy and Civic Renewal. -

Conservative Movement

Conservative Movement How did the conservative movement, routed in Barry Goldwater's catastrophic defeat to Lyndon Johnson in the 1964 presidential campaign, return to elect its champion Ronald Reagan just 16 years later? What at first looks like the political comeback of the century becomes, on closer examination, the product of a particular political moment that united an unstable coalition. In the liberal press, conservatives are often portrayed as a monolithic Right Wing. Close up, conservatives are as varied as their counterparts on the Left. Indeed, the circumstances of the late 1980s -- the demise of the Soviet Union, Reagan's legacy, the George H. W. Bush administration -- frayed the coalition of traditional conservatives, libertarian advocates of laissez-faire economics, and Cold War anti- communists first knitted together in the 1950s by William F. Buckley Jr. and the staff of the National Review. The Reagan coalition added to the conservative mix two rather incongruous groups: the religious right, primarily provincial white Protestant fundamentalists and evangelicals from the Sunbelt (defecting from the Democrats since the George Wallace's 1968 presidential campaign); and the neoconservatives, centered in New York and led predominantly by cosmopolitan, secular Jewish intellectuals. Goldwater's campaign in 1964 brought conservatives together for their first national electoral effort since Taft lost the Republican nomination to Eisenhower in 1952. Conservatives shared a distaste for Eisenhower's "modern Republicanism" that largely accepted the welfare state developed by Roosevelt's New Deal and Truman's Fair Deal. Undeterred by Goldwater's defeat, conservative activists regrouped and began developing institutions for the long haul. -

Commenting on the Issues of the Moment

Conversations with Bill Kristol Guest: Yuval Levin, National Affairs Taped July 29, 2014 Table of Contents I: National Affairs 0:15 – 13:45 II: Working in the White House 13:45 – 29:41 III: Battling Bureaucracy 29:41 – 45:28 IV: Burke and Modern Conservatism 45:28 – 1:04:26 V: Political Philosophy and Politics 1:04:26 – 1:18:02 I: National Affairs (0:15 – 13:45) KRISTOL: Welcome back to CONVERSATIONS. Our guest today is Yuval Levin, policy analyst, policy practitioner, a former White House staffer. And among other things, now editor of the very fine journal, National Affairs. What is National Affairs? Why National Affairs? LEVIN: Well, thank you. National Affairs is a quarterly journal of essays on domestic policy and political thought – political ideas. It tries to sit at the intersection of policy – concrete policy – and political theory and political thought. It exists really because in the wake of the 2008 elections, after a series of conversations among people on the right, including you, among others, we came to the view that one of the things that were missing on the right was a venue for people to think out loud in a serious way, both about policy ideas where the policy agenda seemed to be a little empty, and about political ideas about how, about what conservatism should mean in the 21st century and how that might apply to people’s lives. And we had a clear model. The model really was The Public Interest, which had run for 40 years and which had shut down about five years before that. -

United States: National Affairs, Anti-Semitism

United States National Affairs TheBush administration began the year buoyed by the results of the November 2004 elections: the president's decisive reelection and a strong Republican showing in the congressional races in which the party, already in control of both houses, gained four seats in the Senate and three in the House. The president promised to spend the "political capi- tal" he had earned on an agenda that included Social Security reform, tax cuts, and the continuation of an aggressive global war on terror. The organized Jewish community, meanwhile, geared up for another four years of an administration strongly allied with most Jews on Israel's defense needs, defiantly committed to an increasingly complicated and controversial war in Iraq, and diverging sharply from the majority of American Jews on many domestic issues. THE POLITICAL ARENA olected President Ldent Bush won immediate praise from Jewish leaders for his intment of Judge Michael Chertoff, the son of a rabbi, as secretary meland security. Chertoff had been a widely respected prosecutor hen chief of the Justice Department's criminal division before be- a judge on the Third Circuit of the U.S. Court ofAppeals. He jominated for his new post on January 11 and confirmed by the e on February 15. Another appointment of a prominent Jew was )f Elliott Abrams, who had held a variety of government positions, deputy assistant to the president and deputy national security )ther presidential appointments were generally applauded by the ommunity. Condoleezza Rice, seen as a friend of Israel, moved ional security advisor to secretary of state.