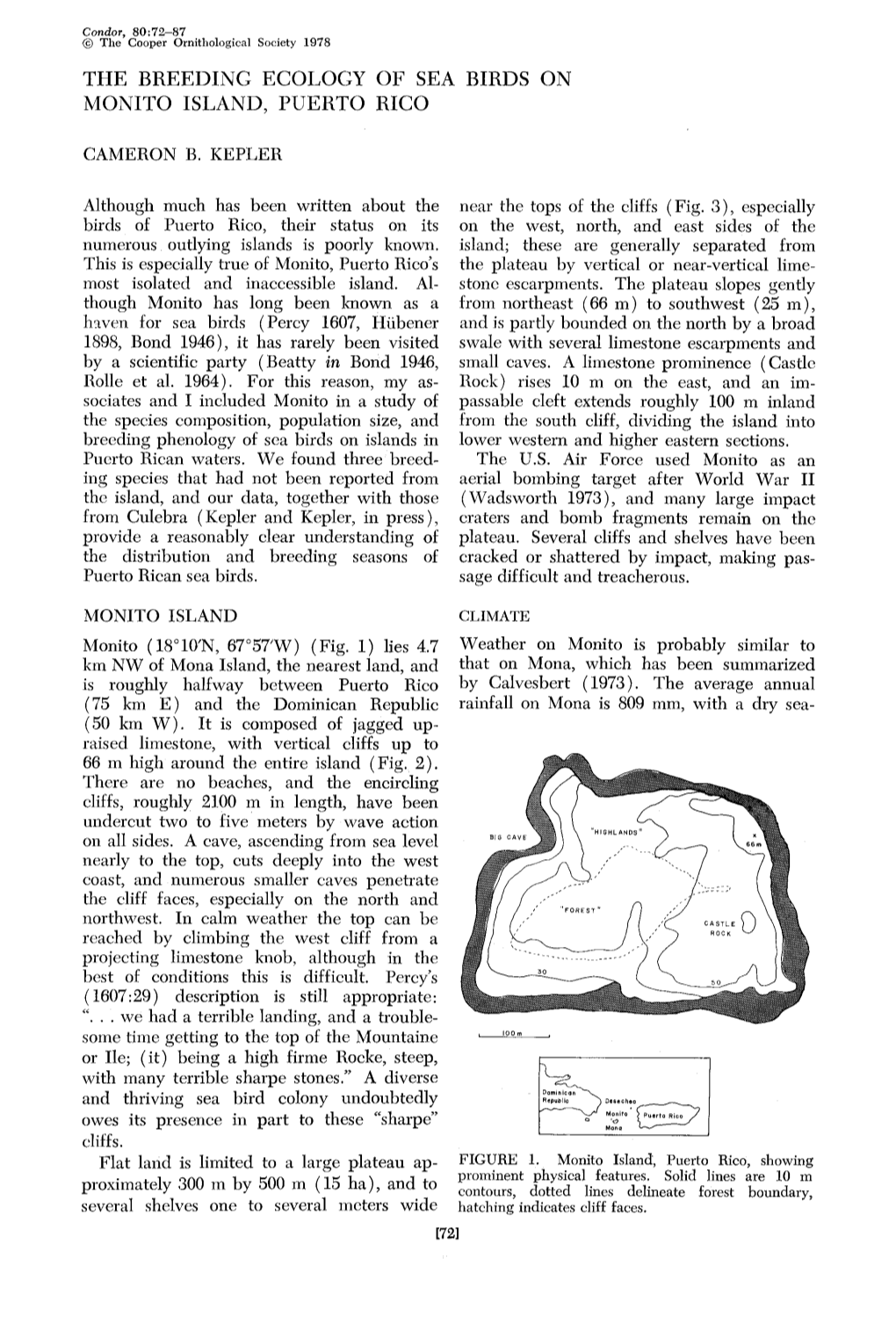

The Breeding Ecology of Sea Birds on Monito Island, Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge BIRD LIST

Merrritt Island National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service P.O. Box 2683 Titusville, FL 32781 http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Merritt_Island 321/861 0669 Visitor Center Merritt Island U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1 800/344 WILD National Wildlife Refuge March 2019 Bird List photo: James Lyon Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, located just Seasonal Occurrences east of Titusville, shares a common boundary with the SP - Spring - March, April, May John F. Kennedy Space Center. Its coastal location, SU - Summer - June, July, August tropic-like climate, and wide variety of habitat types FA - Fall - September, October, November contribute to Merritt Island’s diverse bird population. WN - Winter - December, January, February The Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee lists 521 species of birds statewide. To date, 359 You may see some species outside the seasons indicated species have been identified on the refuge. on this checklist. This phenomenon is quite common for many birds. However, the checklist is designed to Of special interest are breeding populations of Bald indicate the general trend of migration and seasonal Eagles, Brown Pelicans, Roseate Spoonbills, Reddish abundance for each species and, therefore, does not Egrets, and Mottled Ducks. Spectacular migrations account for unusual occurrences. of passerine birds, especially warblers, occur during spring and fall. In winter tens of thousands of Abundance Designation waterfowl may be seen. Eight species of herons and C – Common - These birds are present in large egrets are commonly observed year-round. numbers, are widespread, and should be seen if you look in the correct habitat. Tips on Birding A good field guide and binoculars provide the basic U – Uncommon - These birds are present, but because tools useful in the observation and identification of of their low numbers, behavior, habitat, or distribution, birds. -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas

Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas MEDITERRANEAN AND BLACK SEA BASINS Main seas, straits and gulfs in the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, together with locations mentioned in the text for the distribution of marine mammals and sea turtles Ukraine Russia SEA OF AZOV Kerch Strait Crimea Romania Georgia Slovenia France Croatia BLACK SEA Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Monaco Bosphorus LIGURIAN SEA Montenegro Strait Pelagos Sanctuary Gulf of Italy Lion ADRIATIC SEA Albania Corsica Drini Bay Spain Dardanelles Strait Greece BALEARIC SEA Turkey Sardinia Algerian- TYRRHENIAN SEA AEGEAN SEA Balearic Islands Provençal IONIAN SEA Syria Basin Strait of Sicily Cyprus Strait of Sicily Gibraltar ALBORAN SEA Hellenic Trench Lebanon Tunisia Malta LEVANTINE SEA Israel Algeria West Morocco Bank Tunisian Plateau/Gulf of SirteMEDITERRANEAN SEA Gaza Strip Jordan Suez Canal Egypt Gulf of Sirte Libya RED SEA Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas Compiled by María del Mar Otero and Michela Conigliaro The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by Compiled by María del Mar Otero IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain © IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Malaga, Spain Michela Conigliaro IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Copyright © 2012 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources With the support of Catherine Numa IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Annabelle Cuttelod IUCN Species Programme, United Kingdom Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the sources are fully acknowledged. -

Baja California Sur, Mexico)

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Geomorphology of a Holocene Hurricane Deposit Eroded from Rhyolite Sea Cliffs on Ensenada Almeja (Baja California Sur, Mexico) Markes E. Johnson 1,* , Rigoberto Guardado-France 2, Erlend M. Johnson 3 and Jorge Ledesma-Vázquez 2 1 Geosciences Department, Williams College, Williamstown, MA 01267, USA 2 Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Ensenada 22800, Baja California, Mexico; [email protected] (R.G.-F.); [email protected] (J.L.-V.) 3 Anthropology Department, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70018, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-413-597-2329 Received: 22 May 2019; Accepted: 20 June 2019; Published: 22 June 2019 Abstract: This work advances research on the role of hurricanes in degrading the rocky coastline within Mexico’s Gulf of California, most commonly formed by widespread igneous rocks. Under evaluation is a distinct coastal boulder bed (CBB) derived from banded rhyolite with boulders arrayed in a partial-ring configuration against one side of the headland on Ensenada Almeja (Clam Bay) north of Loreto. Preconditions related to the thickness of rhyolite flows and vertical fissures that intersect the flows at right angles along with the specific gravity of banded rhyolite delimit the size, shape and weight of boulders in the Almeja CBB. Mathematical formulae are applied to calculate the wave height generated by storm surge impacting the headland. The average weight of the 25 largest boulders from a transect nearest the bedrock source amounts to 1200 kg but only 30% of the sample is estimated to exceed a full metric ton in weight. -

Bird Checklist for St. Johns County Florida (As of January 2019)

Bird Checklist for St. Johns County Florida (as of January 2019) DUCKS, GEESE, AND SWANS Mourning Dove Black-bellied Whistling-Duck CUCKOOS Snow Goose Yellow-billed Cuckoo Ross's Goose Black-billed Cuckoo Brant NIGHTJARS Canada Goose Common Nighthawk Mute Swan Chuck-will's-widow Tundra Swan Eastern Whip-poor-will Muscovy Duck SWIFTS Wood Duck Chimney Swift Blue-winged Teal HUMMINGBIRDS Cinnamon Teal Ruby-throated Hummingbird Northern Shoveler Rufous Hummingbird Gadwall RAILS, CRANES, and ALLIES American Wigeon King Rail Mallard Virginia Rail Mottled Duck Clapper Rail Northern Pintail Sora Green-winged Teal Common Gallinule Canvasback American Coot Redhead Purple Gallinule Ring-necked Duck Limpkin Greater Scaup Sandhill Crane Lesser Scaup Whooping Crane (2000) Common Eider SHOREBIRDS Surf Scoter Black-necked Stilt White-winged Scoter American Avocet Black Scoter American Oystercatcher Long-tailed Duck Black-bellied Plover Bufflehead American Golden-Plover Common Goldeneye Wilson's Plover Hooded Merganser Semipalmated Plover Red-breasted Merganser Piping Plover Ruddy Duck Killdeer GROUSE, QUAIL, and ALLIES Upland Sandpiper Northern Bobwhite Whimbrel Wild Turkey Long-billed Curlew GREBES Hudsonian Godwit Pied-billed Grebe Marbled Godwit Horned Grebe Ruddy Turnstone FLAMINGOS Red Knot American Flamingo (2004) Ruff PIGEONS and DOVES Stilt Sandpiper Rock Pigeon Sanderling Eurasian Collared-Dove Dunlin Common Ground-Dove Purple Sandpiper White-winged Dove Baird's Sandpiper St. Johns County is a special place for birds – celebrate it! Bird Checklist -

Two New Scorpions from the Puerto Rican Island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae)

Two new scorpions from the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae) Rolando Teruel, Mel J. Rivera & Carlos J. Santos September 2015 — No. 208 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

Dynamics of Beach Sand Made Easy

Dynamics of Beaches Made Easy Page 1 Dynamics Of Beaches Made Easy San Diego County Chapter of the Surfrider Foundation 1. Introduction Beaches are made up of more than just sand. In California beaches are generally formed by erosion of uplifted plates resulting in cliff backed beaches or in the delta areas of rivers or watersheds. Beach sand is an important element of beaches but not the only element. Wavecut platforms or tidal terraces are equally important in many areas of San Diego. The movement of beach sand is governed by many complex processes and variables. However, there are a few very basic elements that tend to control not only how much sand ends up on our beaches, but also how much sand exists near enough to the shore to be deposited on the beach under favorable conditions. The following is a brief description of the most important issues influencing the current condition of our local beaches with respect to sand. Dynamics of Beaches Made Easy Page 2 2. Geology The geology of San Diego County varies from sea cliffs to sandy beaches. Beaches are generally found at the mouths of lagoons or in the lagoon or river outfalls. Cliffs formed by tectonic activity and the erosion via marine forces deserve special mention. Much of San Diego’s coastline consists of a wavecut platform sometimes referred to as a tidal terrace. A wavecut platform is formed where a seacliff is eroded by marine action, meaning waves, resulting in the deposition of cliff material and formation of a bedrock area where erosion occurred. -

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY of the PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. July 1981 VIRGIN ISLANDS CULEBRA PUERTO RlCO Fig. 1. Map of the Puerto Rican Island Shelf. Rectangles A - E indicate boundaries of maps presented in more detail in Appendix I. 1. Cayo Santiago, 2. Cayo Batata, 3. Cayo de Afuera, 4. Cayo de Tierra, 5. Cardona Key, 6. Protestant Key, 7. Green Key (st. ~roix), 8. Caiia Azul ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN 251 ERRATUM The following caption should be inserted for figure 7: Fig. 7. Temperature in and near a small clump of vegetation on Cayo Ahogado. Dots: 5 cm deep in soil under clump. Circles: 1 cm deep in soil under clump. Triangles: Soil surface under clump. Squares: Surface of vegetation. X's: Air at center of clump. Broken line indicates intervals of more than one hour between measurements. BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwolel, Richard Levins2 and Michael D. Byer3 INTRODUCTION There has been a recent surge of interest in the biogeography of archipelagoes owing to a reinterpretation of classical concepts of evolution of insular populations, factors controlling numbers of species on islands, and the dynamics of inter-island dispersal. The literature on these subjects is rapidly accumulating; general reviews are presented by Mayr (1963) , and Baker and Stebbins (1965) . Carlquist (1965, 1974), Preston (1962 a, b), ~ac~rthurand Wilson (1963, 1967) , MacArthur et al. (1973) , Hamilton and Rubinoff (1963, 1967), Hamilton et al. (1963) , Crowell (19641, Johnson (1975) , Whitehead and Jones (1969), Simberloff (1969, 19701, Simberloff and Wilson (1969), Wilson and Taylor (19671, Carson (1970), Heatwole and Levins (1973) , Abbott (1974) , Johnson and Raven (1973) and Lynch and Johnson (1974), have provided major impetuses through theoretical and/ or general papers on numbers of species on islands and the dynamics of insular biogeography and evolution. -

Us Caribbean Regional Coral Reef Fisheries Management Workshop

Caribbean Regional Workshop on Coral Reef Fisheries Management: Collaboration on Successful Management, Enforcement and Education Methods st September 30 - October 1 , 2002 Caribe Hilton Hotel San Juan, Puerto Rico Workshop Objective: The regional workshop allowed island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to identify successful coral reef fishery management approaches. The workshop provided the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force with recommendations by local, regional and national stakeholders, to develop more effective and appropriate regional planning for coral reef fisheries conservation and sustainable use. The recommended priorities will assist Federal agencies to provide more directed grant and technical assistance to the U.S. Caribbean. Background: Coral reefs and associated habitats provide important commercial, recreational and subsistence fishery resources in the United States and around the world. Fishing also plays a central social and cultural role in many island communities. However, these fishery resources and the ecosystems that support them are under increasing threat from overfishing, recreational use, and developmental impacts. This workshop, held in conjunction with the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force Meeting, brought together island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel to compare methods that have been successful, including regulations that have worked, effective enforcement, and education to reach people who can really effect change. These efforts were supported by Federal fishery managers and scientists, Puerto Rico Sea Grant, and drew on the experience of researchers working in the islands and Florida. The workshop helped develop approaches for effective fishery management strategies in the U.S. Caribbean and recommended priority actions to the U.S. -

Broome and Is Accessed Via Crab Creek Rd (Sign-Posted at the Junction of Broome and Crab Creek Rds)

Birdwatching around Broome Broome is world famous for its spectacular birdlife, with over 325 species recorded in the region. Excellent birding can be had throughout the year. NB The wet season Birdwatching occasionally affects access to the prime birding areas. Bird Sites There are six distinct habitats in the region and all are around relatively close to the town itself. They are mangrove, salt Broome Region marsh, open plains, mudflats, pindan woodland and coastal scrub interspersed with vine thickets Broome Barred Creek 6 Bar-shouldered Manari Road 0 5 Km Dove Scale Broome-Cape Levique Road Acknowledgements Illustrations / photographs: P Agar, R Ashford, P Barrett, Willie Creek J Baas, N Davies, P Marsack, M Morcombe, F O’Connor, 6 G Steytler, C Tate, S Tingay, J Vogel. Contacts Broome Bird Observatory Phone: (08) 9193 5600 Email: [email protected] Web: www.broomebirdobservatory.com Facebook: https://facebook.com/broomebirdobs / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Broome / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / 7/ / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Guide No 3A / / / / / / / / / / / / Roebuck/ / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / -

The Genus Sula in the Carolinas: an Overview of the Phenology And

h Gn Sl n th Crln: An Ovrv f th hnl nd trbtn f Gnnt nd b n th Sth Atlnt ht DAVID S. LEE and J. CHRISTOPHER HANEY Five of the eight recognized species of the genus Sula are known from the southeastern United States. Of these only the Northern Gannet (Sula bassana) occurs regularly in the Carolinas, but both the Masked Booby (S. dactylatra), formerly Blue- faced, and the Brown Booby (S. leucogaster) have been reported from North and South Carolina. Of the two remaining species, the Red-footed Booby (S. sula) is generally restricted to the Caribbean and disperses northward into the Florida Keys and Gulf of Mexico, whereas the Blue-footed Booby (S. nebouxii) is an eastern Pacific species with one accidental and astonishing record from south Padre Island, Texas (5 October 1976, photograph Amer. Birds 31:349-351). Generally the records for locally occurring Sula, excluding wintering Northern Gannets, are less than adequate as conclusive evidence of seasonal or geographical occurrence. Most problems result from confusing plumages of the various species and the general lack of experience of North American bird students with boobies. An additional problem is the fact that until very recently most ornithologists believed that boobies occurred off the south Atlantic states, outside Florida, only as rare accidentals, causing many records to be viewed with excessive caution and skepticism. Potter et al. (1980), for example, associated all records of boobies in the Carolinas with storms. In recent years few groups of birds have caused as many interpretive problems for the Carolina Bird Club's North Carolina Records Committee as have the Sula. -

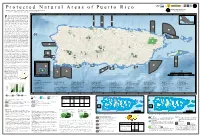

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia.