LEAFY Maintains Apical Stem Cell Activity During Shoot Development In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Analysis of Pinus Pinaster Snrks Reveals Clues of the Evolution of This Family and a New Set of Abiotic Stress Resistance Biomarkers

agronomy Article The Analysis of Pinus pinaster SnRKs Reveals Clues of the Evolution of This Family and a New Set of Abiotic Stress Resistance Biomarkers Francisco Javier Colina * , María Carbó , Ana Álvarez , Luis Valledor * and María Jesús Cañal Plant Physiology, Department of Organisms and Systems Biology and University Institute of Biotechnology (IUBA), University of Oviedo, 33006 Oviedo, Spain; [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (A.Á.); [email protected] (M.J.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (F.J.C.); [email protected] (L.V.) Received: 15 January 2020; Accepted: 17 February 2020; Published: 19 February 2020 Abstract: Climate change is increasing the intensity and incidence of environmental stressors, reducing the biomass yields of forestry species as Pinus pinaster. Selection of new stress-tolerant varieties is thus required. Many genes related to plant stress signaling pathways have proven useful for this purpose with sucrose non-fermenting related kinases (SnRK), conserved across plant evolution and connected to different phosphorylation cascades within ABA- and Ca2+-mediated signaling pathways, as a good example. The modulation of SnRKs and/or the selection of specific SnRK alleles have proven successful strategies to increase plant stress resistance. Despite this, SnRKs have been barely studied in gymnosperms. In this work P. pinaster SnRK sequences (PpiSnRK) were identified through a homology- and domain-based sequence analysis using Arabidopsis SnRK sequences as query. Moreover, PpiSnRKs links to the gymnosperm stress response were modeled out of the known interactions of PpiSnRKs orthologs from other species with different signaling complexity. This approach successfully identified the pine SnRK family and predicted their central role into the gymnosperm stress response, linking them to ABA, Ca2+, sugar/energy and possibly ethylene signaling. -

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

The Origin of Alternation of Generations in Land Plants

Theoriginof alternation of generations inlandplants: afocuson matrotrophy andhexose transport Linda K.E.Graham and LeeW .Wilcox Department of Botany,University of Wisconsin, 430Lincoln Drive, Madison,WI 53706, USA (lkgraham@facsta¡.wisc .edu ) Alifehistory involving alternation of two developmentally associated, multicellular generations (sporophyteand gametophyte) is anautapomorphy of embryophytes (bryophytes + vascularplants) . Microfossil dataindicate that Mid ^Late Ordovicianland plants possessed such alifecycle, and that the originof alternationof generationspreceded this date.Molecular phylogenetic data unambiguously relate charophyceangreen algae to the ancestryof monophyletic embryophytes, and identify bryophytes as early-divergentland plants. Comparison of reproduction in charophyceans and bryophytes suggests that the followingstages occurredduring evolutionary origin of embryophytic alternation of generations: (i) originof oogamy;(ii) retention ofeggsand zygotes on the parentalthallus; (iii) originof matrotrophy (regulatedtransfer ofnutritional and morphogenetic solutes fromparental cells tothe nextgeneration); (iv)origin of a multicellularsporophyte generation ;and(v) origin of non-£ agellate, walled spores. Oogamy,egg/zygoteretention andmatrotrophy characterize at least some moderncharophyceans, and arepostulated to represent pre-adaptativefeatures inherited byembryophytes from ancestral charophyceans.Matrotrophy is hypothesizedto have preceded originof the multicellularsporophytes of plants,and to represent acritical innovation.Molecular -

Ovule and Embryo Development, Apomixis and Fertilization Abdul M Chaudhury, Stuart Craig, ES Dennis and WJ Peacock

26 Ovule and embryo development, apomixis and fertilization Abdul M Chaudhury, Stuart Craig, ES Dennis and WJ Peacock Genetic analyses, particularly in Arabidopsis, have led to Figure 1 the identi®cation of mutants that de®ne different steps of ovule ontogeny, pollen stigma interaction, pollen tube growth, and fertilization. Isolation of the genes de®ned by these Micropyle mutations promises to lead to a molecular understanding of (a) these processes. Mutants have also been obtained in which Synergid processes that are normally triggered by fertilization, such as endosperm formation and initiation of seed development, Egg cell occur without fertilization. These mutants may illuminate Polar Nuclei apomixis, a process of seed development without fertilization extant in many plants. Antipodal cells Chalazi Address Female Gametophyte CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO BOX 1600, ACT 2601, Australia; e-mail:[email protected] (b) (c) Current Opinion in Plant Biology 1998, 1:26±31 Pollen tube Funiculus http://biomednet.com/elecref/1369526600100026 Integument Zygote Fusion of Current Biology Ltd ISSN 1369-5266 egg and Primary sperm nuclei Endosperm Abbreviations cell ®s fertilization-independent seed Fused Polar ®e fertilization-independent endosperm Nuclei and Sperm Double Fertilization Introduction Ovules are critical in plant sexual reproduction. They (d) (e) contain a nucellus (the site of megasporogenesis), one or two integuments that develop into the seed coat and Globular a funiculus that connects the ovule to the ovary wall. embryo Embryo The nucellar megasporangium produces meiotic cells, one of which subsequently undergoes megagametogenesis to Endosperm produce the mature female gametophyte containing eight haploid nuclei [1] (Figure 1). One of these eight nuclei becomes the egg. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

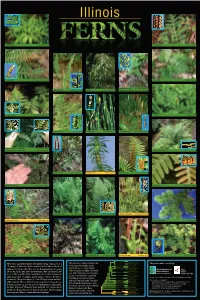

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Plant Evolution and Diversity B. Importance of Plants C. Where Do Plants Fit, Evolutionarily? What Are the Defining Traits of Pl

Plant Evolution and Diversity Reading: Chap. 30 A. Plants: fundamentals I. What is a plant? What does it do? A. Basic structure and function B. Why are plants important? - Photosynthesize C. What are plants, evolutionarily? -CO2 uptake D. Problems of living on land -O2 release II. Overview of major plant taxa - Water loss A. Bryophytes (seedless, nonvascular) - Water and nutrient uptake B. Pterophytes (seedless, vascular) C. Gymnosperms (seeds, vascular) -Grow D. Angiosperms (seeds, vascular, and flowers+fruits) Where? Which directions? II. Major evolutionary trends - Reproduce A. Vascular tissue, leaves, & roots B. Fertilization without water: pollen C. Dispersal: from spores to bare seeds to seeds in fruits D. Life cycles Æ reduction of gametophyte, dominance of sporophyte Fig. 1.10, Raven et al. B. Importance of plants C. Where do plants fit, evolutionarily? 1. Food – agriculture, ecosystems 2. Habitat 3. Fuel and fiber 4. Medicines 5. Ecosystem services How are protists related to higher plants? Algae are eukaryotic photosynthetic organisms that are not plants. Relationship to the protists What are the defining traits of plants? - Multicellular, eukaryotic, photosynthetic autotrophs - Cell chemistry: - Chlorophyll a and b - Cell walls of cellulose (plus other polymers) - Starch as a storage polymer - Most similar to some Chlorophyta: Charophyceans Fig. 29.8 Points 1. Photosynthetic protists are spread throughout many groups. 2. Plants are most closely related to the green algae, in particular, to the Charophyceans. Coleochaete 3. -

Basic Plant and Flower Parts

Basic Plant and Flower Parts Basic Parts of a Plant: Bud - the undeveloped flower of a plant Flower - the reproductive structure in flowering plants where seeds are produced Fruit - the ripened ovary of a plant that contains the seeds; becomes fleshy or hard and dry after fertilization to protect the developing seeds Leaf - the light absorbing structure and food making factory of plants; site of photosynthesis Root - anchors the plant and absorbs water and nutrients from the soil Seed - the ripened ovule of a plant, containing the plant embryo, endosperm (stored food), and a protective seed coat Stem - the support structure for the flowers and leaves; includes a vascular system (xylem and phloem) for the transport of water and food Vein - vascular structure in the leaf Basic Parts of a Flower: Anther - the pollen-bearing portion of a stamen Filament - the stalk of a stamen Ovary - the structure that encloses the undeveloped seeds of a plant Ovules - female reproductive cells of a plant Petal - one of the innermost modified leaves surrounding the reproductive organs of a plant; usually brightly colored Pistil - the female part of the flower, composed of the ovary, stigma, and style Pollen - the male reproductive cells of plants Sepal - one of the outermost modified leaves surrounding the reproductive organs of a plant; usually green Stigma - the tip of the female organ in plants, where the pollen lands Style - the stalk, or middle part, of the female organ in plants (connecting the stigma and ovary) Stamen - the male part of the flower, composed of the anther and filament; the anther produces pollen Pistil Stigma Stamen Style Anther Pollen Filament Petal Ovule Sepal Ovary Flower Vein Bud Stem Seed Fruit Leaf Root . -

EXTENSION EC1257 Garden Terms: Reproductive Plant Morphology — Black/PMS 186 Seeds, Flowers, and Fruitsextension

4 color EXTENSION EC1257 Garden Terms: Reproductive Plant Morphology — Black/PMS 186 Seeds, Flowers, and FruitsEXTENSION Anne Streich, Horticulture Educator Seeds Seed Formation Seeds are a plant reproductive structure, containing a Pollination is the transfer of pollen from an anther to a fertilized embryo in an arrestedBlack state of development, stigma. This may occur by wind or by pollinators. surrounded by a hard outer covering. They vary greatly Cross pollinated plants are fertilized with pollen in color, shape, size, and texture (Figure 1). Seeds are EXTENSION from other plants. dispersed by a variety of methods including animals, wind, and natural characteristics (puffball of dandelion, Self-pollinated plants are fertilized with pollen wings of maples, etc.). from their own fl owers. Fertilization is the union of the (male) sperm nucleus from the pollen grain and the (female) egg nucleus found in the ovary. If fertilization is successful, the ovule will develop into a seed and the ovary will develop into a fruit. Seed Characteristics Seed coats are the hard outer covering of seeds. They protect seed from diseases, insects and unfavorable environmental conditions. Water must be allowed through the seed coat for germination to occur. Endosperm is a food storage tissue found in seeds. It can be made up of proteins, carbohydrates, or fats. Embryos are immature plants in an arrested state of development. They will begin growth when Figure 1. A seed is a small embryonic plant enclosed in a environmental conditions are favorable. covering called the seed coat. Seeds vary in color, shape, size, and texture. Germination is the process in which seeds begin to grow. -

Evolution of the Life Cycle in Land Plants

Journal of Systematics and Evolution 50 (3): 171–194 (2012) doi: 10.1111/j.1759-6831.2012.00188.x Review Evolution of the life cycle in land plants ∗ 1Yin-Long QIU 1Alexander B. TAYLOR 2Hilary A. McMANUS 1(Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA) 2(Department of Biological Sciences, Le Moyne College, Syracuse, NY 13214, USA) Abstract All sexually reproducing eukaryotes have a life cycle consisting of a haploid and a diploid phase, marked by meiosis and syngamy (fertilization). Each phase is adapted to certain environmental conditions. In land plants, the recently reconstructed phylogeny indicates that the life cycle has evolved from a condition with a dominant free-living haploid gametophyte to one with a dominant free-living diploid sporophyte. The latter condition allows plants to produce more genotypic diversity by harnessing the diversity-generating power of meiosis and fertilization, and is selectively favored as more solar energy is fixed and fed into the biosystem on earth and the environment becomes more heterogeneous entropically. Liverworts occupy an important position for understanding the origin of the diploid generation in the life cycle of land plants. Hornworts and lycophytes represent critical extant transitional groups in the change from the gametophyte to the sporophyte as the independent free-living generation. Seed plants, with the most elaborate sporophyte and the most reduced gametophyte (except the megagametophyte in many gymnosperms), have the best developed sexual reproduction system that can be matched only by mammals among eukaryotes: an ancient and stable sex determination mechanism (heterospory) that enhances outcrossing, a highly bimodal and skewed distribution of sperm and egg numbers, a male-driven mutation system, female specialization in mutation selection and nourishment of the offspring, and well developed internal fertilization. -

Secreted Molecules and Their Role in Embryo Formation in Plants : a Min-Review

Secreted molecules and their role in embryo formation in plants : a min-review. Elisabeth Matthys-Rochon To cite this version: Elisabeth Matthys-Rochon. Secreted molecules and their role in embryo formation in plants : a min- review.. acta Biologica Cracoviensia, 2005, pp.23-29. hal-00188834 HAL Id: hal-00188834 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00188834 Submitted on 31 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright ACTA BIOLOGICA CRACOVIENSIA Series Botanica 47/1: 23–29, 2005 SECRETED MOLECULES AND THEIR ROLE IN EMBRYO FORMATION IN PLANTS: A MINI-REVIEW ELISABETH MATTHYS-ROCHON* Reproduction et développement des plantes (RDP), UMR 5667 CNRS/INRA/ENS/LYON1, 46 Allée d’Italie, 69364 Lyon Cedex 07, France Received January 15, 2005; revision accepted April 2, 2005 This short review emphasizes the importance of secreted molecules (peptides, proteins, arabinogalactan proteins, PR proteins, oligosaccharides) produced by cells and multicellular structures in culture media. Several of these molecules have also been identified in planta within the micro-environment in which the embryo and endosperm develop. Questions are raised about the parallel between in vitro systems (somatic and androgenetic) and in planta zygotic development. -

Seed Development in Citrus

SEED DEVELOPMENT IN CITRUS L. K. JACKSON; Revisedby F. G. GMITTER, JR. ProfessorEmeritus and AssociateProfessor, Department of Horticultural Sciences,University of Florida, Citrus Researchand EducationCenter, Lake Alfred, FL 33850 Becauseseed development is necessarilya part of the developmentof fruit. it is important to considerthe processesresponsible for seeddevelopment and someof the reasonsfor the lack of seedsin somecases. We will then turn attentionto the actual growth and developmentof the seed within the fruit. Lastly, we needto considerthe horticultural significanceof seedproduction and especiallysome of the uniquefeatures of citrus seedswhich makethem both an assetand a liability for growersand researchscientists. Citrus Flower and Fruit MoQ1holo~. There are 2 main types of bloom in citrus. Leafy bloom occurswhen flowers form on and with new vegetativegrowth in the spring. The vegetative growth of the elongating shoot is transformedinto a tenninal inflorescenceof 1 or more flowers about the time lateral shootsemerge from bud scales.Other flowers are produceddirectly in leaf axils of previous growth flushesand are termedbouquet bloom. As a vegetative growth point is transfonned into a flower bud, it becomes broadened and flattened, forming a floral apical meristem. Each flower part is fonned from the outside in (acropetally). The sepal (button) primordia are fonned first, then those of the petals, the anthers and finally the carpels which will form the segments. The female flower parts (pistil) are composed by fusion of a whorl of approximately 10 carpels. The cavities fonned by fusion of the carpels are called locules. Each locule contains 2 vertical rows of ovules (Fig. 1), that can develop into seeds. Fig. 1. Diagrammaticportrayal of opencitrus flower. -

Reproductive Morphology

Week 3; Wednesday Announcements: 1st lab quiz TODAY Reproductive Morphology Reproductive morphology - any portion of a plant that is involved with or a direct product of sexual reproduction Example: cones, flowers, fruits, seeds, etc. Basic Plant Life cycle Our view of the importance of gametes in the life cycle is shaped by the animal life cycle in which meiosis (the cell division creating haploid daughter cells with only one set of chromosomes) gives rise directly to sperm and eggs which are one celled and do not live independently. Fertilization (or the fusion of gametes – sperm and egg) occurs inside the animal to recreate the diploid organism (2 sets of chromosomes). Therefore, this life cycle is dominated by the diploid generation. This is NOT necessarily the case among plants! Generalized life cycle -overhead- - alternation of generations – In plants, spores are the result of meiosis. These may grow into a multicellular, independent organism (gametophyte – “gamete-bearer”), which eventually produces sperm and eggs (gametes). These fuse (fertilization) and a zygote is formed which grows into what is known as a sporophyte - “spore-bearer”. (In seed plants, pollination must occur before fertilization! ) This sporophyte produces structures called sporangia in which meiosis occurs and the spores are released. Spores (the product of meiosis) are the first cell of the gametophyte generation. Distinguish Pollination from Fertilization and Spore from Gamete Pollination – the act of transferring pollen from anther or male cone to stigma or female cone; restricted to seed plants. Fertilization – the act of fusion between sperm and egg – must follow pollination in seed plants; fertilization occurs in all sexually reproducing organisms.