Embryo Development in Carica Papaya Linn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

Pharmacognostic Investigations on the Seeds of Carica Papaya L

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2019; 8(5): 2185-2193 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 JPP 2019; 8(5): 2185-2193 Pharmacognostic investigations on the seeds of Received: 24-07-2019 Accepted: 28-08-2019 Carica papaya L. Savan Donga Phytochemical, Pharmacological Savan Donga, Jyoti Pande and Sumitra Chanda and Microbiological laboratory, Department of Biosciences Abstract (UGC-CAS), Saurashtra Carica papaya L. belongs to the family Caricaceae and is commonly known as papaya. All parts of the University, Rajkot, Gujarat, India plant are traditionally used for curing various diseases and disorders. It is a tropical fruit well known for its flavor and nutritional properties. Unripe and ripe fruit of papaya is edible but the seeds are thrown Jyoti Pande away. Instead, they can be therapeutically used. Natural drugs are prone to adulteration and substitution; Phytochemical, Pharmacological to prevent it, it is always essential to lay down quality control and standardization parameters. Hence, the and Microbiological laboratory, objectives of the present work were pharmacognostic, physicochemical and phytochemical studies of Department of Biosciences Carica papaya L. un-ripe and ripe seeds. Macroscopic, microscopic and powder features, phytochemical, (UGC-CAS), Saurashtra physicochemical properties and fluorescence characteristics were determined using standard methods. University, Rajkot, Gujarat, The seeds were of clavate shape, hilum was of wavy type, margin was smooth, unripe seed was creamiest India white in colour while ripe seed was dark black in colour. The microscopic study showed seed was divided into four parts epicarp, mesocarp, testa and endocarp. The epicarp was single layered with thin Sumitra Chanda smooth cuticle layer, polygonal parenchymatous cells. -

The Origin of Alternation of Generations in Land Plants

Theoriginof alternation of generations inlandplants: afocuson matrotrophy andhexose transport Linda K.E.Graham and LeeW .Wilcox Department of Botany,University of Wisconsin, 430Lincoln Drive, Madison,WI 53706, USA (lkgraham@facsta¡.wisc .edu ) Alifehistory involving alternation of two developmentally associated, multicellular generations (sporophyteand gametophyte) is anautapomorphy of embryophytes (bryophytes + vascularplants) . Microfossil dataindicate that Mid ^Late Ordovicianland plants possessed such alifecycle, and that the originof alternationof generationspreceded this date.Molecular phylogenetic data unambiguously relate charophyceangreen algae to the ancestryof monophyletic embryophytes, and identify bryophytes as early-divergentland plants. Comparison of reproduction in charophyceans and bryophytes suggests that the followingstages occurredduring evolutionary origin of embryophytic alternation of generations: (i) originof oogamy;(ii) retention ofeggsand zygotes on the parentalthallus; (iii) originof matrotrophy (regulatedtransfer ofnutritional and morphogenetic solutes fromparental cells tothe nextgeneration); (iv)origin of a multicellularsporophyte generation ;and(v) origin of non-£ agellate, walled spores. Oogamy,egg/zygoteretention andmatrotrophy characterize at least some moderncharophyceans, and arepostulated to represent pre-adaptativefeatures inherited byembryophytes from ancestral charophyceans.Matrotrophy is hypothesizedto have preceded originof the multicellularsporophytes of plants,and to represent acritical innovation.Molecular -

Morphological Variation in the Flowers of Jacaratia

Plant Biology ISSN 1435-8603 RESEARCH PAPER Morphological variation in the flowers of Jacaratia mexicana A. DC. (Caricaceae), a subdioecious tree A. Aguirre1, M. Vallejo-Marı´n2, E. M. Piedra-Malago´ n3, R. Cruz-Ortega4 & R. Dirzo5 1 Departamento de Biologı´a Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecologı´a A.C., Congregacio´ n El Haya, Xalapa, Veracruz, Me´ xico 2 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 3 Posgrado Instituto de Ecologı´a A.C., Congregacio´ n El Haya, Xalapa, Veracruz, Me´ xico 4 Departamento de Ecologı´a Funcional, Instituto de Ecologı´a, UNAM, Me´ xico 5 Department of Biological Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA Keywords ABSTRACT Caricaceae; dioecy; Jacaratia mexicana; Mexico; sexual variation. The Caricaceae is a small family of tropical trees and herbs in which most species are dioecious. In the present study, we extend our previous work on Correspondence dioecy in the Caricaceae, characterising the morphological variation in sex- A. Aguirre, Departamento de Biologı´a ual expression in flowers of the dioecious tree Jacaratia mexicana. We found Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecologı´a A.C., Km. 2.5 that, in J. mexicana, female plants produce only pistillate flowers, while Carretera Antigua a Coatepec 351, male plants are sexually variable and can bear three different types of flow- Congregacio´ n El Haya, Xalapa 91070, ers: staminate, pistillate and perfect. To characterise the distinct types of Veracruz, Me´ xico. flowers, we measured 26 morphological variables. Our results indicate that: E-mail: [email protected] (i) pistillate flowers from male trees carry healthy-looking ovules and are morphologically similar, although smaller than, pistillate flowers on female Editor plants; (ii) staminate flowers have a rudimentary, non-functional pistil and M. -

Marker-Assisted Breeding for Papaya Ringspot Virus Resistance in Carica Papaya L

Marker-Assisted Breeding for Papaya Ringspot Virus Resistance in Carica papaya L. Author O'Brien, Christopher Published 2010 Thesis Type Thesis (Masters) School Griffith School of Environment DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3639 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/365618 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Marker-Assisted Breeding for Papaya Ringspot Virus Resistance in Carica papaya L. Christopher O'Brien BAppliedSc (Environmental and Production Horticulture) University of Queensland Griffith School of Environment Science, Environment, Engineering and Technology Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy September 4, 2009 2 Table of Contents Page No. Abstract ……………………………………………………… 11 Statement of Originality ………………………………………........ 13 Acknowledgements …………………………………………. 15 Chapter 1 Literature review ………………………………....... 17 1.1 Overview of Carica papaya L. (papaya)………………… 19 1.1.1 Taxonomy ………………………………………………… . 19 1.1.2 Origin ………………………………………………….. 19 1.1.3 Botany …………………………………………………… 20 1.1.4 Importance …………………………………………………... 25 1.2 Overview of Vasconcellea species ……………………… 28 1.2.1 Taxonomy …………………………………………………… 28 1.2.2 Origin ……………………………………………………… 28 1.2.3 Botany ……………………………………………………… 31 1.2.4 Importance …………………………………………………… 31 1.2.5 Brief synopsis of Vasconcellea species …………………….. 33 1.3 Papaya ringspot virus (PRSV-P)…………………………. 42 1.3.1 Overview ………………………………………………………. 42 1.3.2 Distribution …………………………………………………… 43 1.3.3 Symptoms and effects ……………………………………….. .. 44 1.3.4 Transmission …………………………………………………. 45 1.3.5 Control ………………………………………………………. .. 46 1.4 Breeding ………………………………………………………. 47 1.4.1 Disease resistance …………………………………………….. 47 1.4.2 Biotechnology………………………………………………….. 50 1.4.3 Intergeneric hybridisation…………………………………….. 51 1.4.4 Genetic transformation………………………………………… 54 1.4.5 DNA analysis ………………………………………………..... -

Ovule and Embryo Development, Apomixis and Fertilization Abdul M Chaudhury, Stuart Craig, ES Dennis and WJ Peacock

26 Ovule and embryo development, apomixis and fertilization Abdul M Chaudhury, Stuart Craig, ES Dennis and WJ Peacock Genetic analyses, particularly in Arabidopsis, have led to Figure 1 the identi®cation of mutants that de®ne different steps of ovule ontogeny, pollen stigma interaction, pollen tube growth, and fertilization. Isolation of the genes de®ned by these Micropyle mutations promises to lead to a molecular understanding of (a) these processes. Mutants have also been obtained in which Synergid processes that are normally triggered by fertilization, such as endosperm formation and initiation of seed development, Egg cell occur without fertilization. These mutants may illuminate Polar Nuclei apomixis, a process of seed development without fertilization extant in many plants. Antipodal cells Chalazi Address Female Gametophyte CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO BOX 1600, ACT 2601, Australia; e-mail:[email protected] (b) (c) Current Opinion in Plant Biology 1998, 1:26±31 Pollen tube Funiculus http://biomednet.com/elecref/1369526600100026 Integument Zygote Fusion of Current Biology Ltd ISSN 1369-5266 egg and Primary sperm nuclei Endosperm Abbreviations cell ®s fertilization-independent seed Fused Polar ®e fertilization-independent endosperm Nuclei and Sperm Double Fertilization Introduction Ovules are critical in plant sexual reproduction. They (d) (e) contain a nucellus (the site of megasporogenesis), one or two integuments that develop into the seed coat and Globular a funiculus that connects the ovule to the ovary wall. embryo Embryo The nucellar megasporangium produces meiotic cells, one of which subsequently undergoes megagametogenesis to Endosperm produce the mature female gametophyte containing eight haploid nuclei [1] (Figure 1). One of these eight nuclei becomes the egg. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

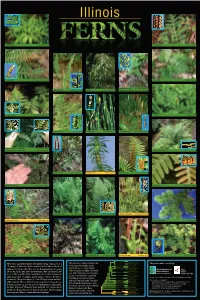

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Plant Evolution and Diversity B. Importance of Plants C. Where Do Plants Fit, Evolutionarily? What Are the Defining Traits of Pl

Plant Evolution and Diversity Reading: Chap. 30 A. Plants: fundamentals I. What is a plant? What does it do? A. Basic structure and function B. Why are plants important? - Photosynthesize C. What are plants, evolutionarily? -CO2 uptake D. Problems of living on land -O2 release II. Overview of major plant taxa - Water loss A. Bryophytes (seedless, nonvascular) - Water and nutrient uptake B. Pterophytes (seedless, vascular) C. Gymnosperms (seeds, vascular) -Grow D. Angiosperms (seeds, vascular, and flowers+fruits) Where? Which directions? II. Major evolutionary trends - Reproduce A. Vascular tissue, leaves, & roots B. Fertilization without water: pollen C. Dispersal: from spores to bare seeds to seeds in fruits D. Life cycles Æ reduction of gametophyte, dominance of sporophyte Fig. 1.10, Raven et al. B. Importance of plants C. Where do plants fit, evolutionarily? 1. Food – agriculture, ecosystems 2. Habitat 3. Fuel and fiber 4. Medicines 5. Ecosystem services How are protists related to higher plants? Algae are eukaryotic photosynthetic organisms that are not plants. Relationship to the protists What are the defining traits of plants? - Multicellular, eukaryotic, photosynthetic autotrophs - Cell chemistry: - Chlorophyll a and b - Cell walls of cellulose (plus other polymers) - Starch as a storage polymer - Most similar to some Chlorophyta: Charophyceans Fig. 29.8 Points 1. Photosynthetic protists are spread throughout many groups. 2. Plants are most closely related to the green algae, in particular, to the Charophyceans. Coleochaete 3. -

Basic Plant and Flower Parts

Basic Plant and Flower Parts Basic Parts of a Plant: Bud - the undeveloped flower of a plant Flower - the reproductive structure in flowering plants where seeds are produced Fruit - the ripened ovary of a plant that contains the seeds; becomes fleshy or hard and dry after fertilization to protect the developing seeds Leaf - the light absorbing structure and food making factory of plants; site of photosynthesis Root - anchors the plant and absorbs water and nutrients from the soil Seed - the ripened ovule of a plant, containing the plant embryo, endosperm (stored food), and a protective seed coat Stem - the support structure for the flowers and leaves; includes a vascular system (xylem and phloem) for the transport of water and food Vein - vascular structure in the leaf Basic Parts of a Flower: Anther - the pollen-bearing portion of a stamen Filament - the stalk of a stamen Ovary - the structure that encloses the undeveloped seeds of a plant Ovules - female reproductive cells of a plant Petal - one of the innermost modified leaves surrounding the reproductive organs of a plant; usually brightly colored Pistil - the female part of the flower, composed of the ovary, stigma, and style Pollen - the male reproductive cells of plants Sepal - one of the outermost modified leaves surrounding the reproductive organs of a plant; usually green Stigma - the tip of the female organ in plants, where the pollen lands Style - the stalk, or middle part, of the female organ in plants (connecting the stigma and ovary) Stamen - the male part of the flower, composed of the anther and filament; the anther produces pollen Pistil Stigma Stamen Style Anther Pollen Filament Petal Ovule Sepal Ovary Flower Vein Bud Stem Seed Fruit Leaf Root . -

EXTENSION EC1257 Garden Terms: Reproductive Plant Morphology — Black/PMS 186 Seeds, Flowers, and Fruitsextension

4 color EXTENSION EC1257 Garden Terms: Reproductive Plant Morphology — Black/PMS 186 Seeds, Flowers, and FruitsEXTENSION Anne Streich, Horticulture Educator Seeds Seed Formation Seeds are a plant reproductive structure, containing a Pollination is the transfer of pollen from an anther to a fertilized embryo in an arrestedBlack state of development, stigma. This may occur by wind or by pollinators. surrounded by a hard outer covering. They vary greatly Cross pollinated plants are fertilized with pollen in color, shape, size, and texture (Figure 1). Seeds are EXTENSION from other plants. dispersed by a variety of methods including animals, wind, and natural characteristics (puffball of dandelion, Self-pollinated plants are fertilized with pollen wings of maples, etc.). from their own fl owers. Fertilization is the union of the (male) sperm nucleus from the pollen grain and the (female) egg nucleus found in the ovary. If fertilization is successful, the ovule will develop into a seed and the ovary will develop into a fruit. Seed Characteristics Seed coats are the hard outer covering of seeds. They protect seed from diseases, insects and unfavorable environmental conditions. Water must be allowed through the seed coat for germination to occur. Endosperm is a food storage tissue found in seeds. It can be made up of proteins, carbohydrates, or fats. Embryos are immature plants in an arrested state of development. They will begin growth when Figure 1. A seed is a small embryonic plant enclosed in a environmental conditions are favorable. covering called the seed coat. Seeds vary in color, shape, size, and texture. Germination is the process in which seeds begin to grow. -

Molecular Phylogeny, Biogeography and an E- Monograph of the Papaya Family (Caricaceae) As an Example of Taxonomy in the Electronic Age

springer.com Fernanda Antunes Carvalho Molecular Phylogeny, Biogeography and an e- Monograph of the Papaya Family (Caricaceae) as an Example of Taxonomy in the Electronic Age 2015, XIV, 147 p. 24 illus. Study in the field of natural sciences Fernanda Antunes Carvalho addresses an issue of key importance to the field of systematics, Printed book namely how to foster taxonomic work and the dissemination of scientific knowledge about Softcover species by taking full advantage of electronic data and bioinformatics tools. The first part 99,99 € | £89.99 | $119.99 focuses on the development of an electronic monograph of the papaya family (Caricaceae) [1]106,99 € (D) | 109,99 € (A) | CHF using existing infrastructures of Information Technology (IT) and bioinformatic tools that 118,00 together set the stage for a new era of systematics. Based on the plastid and nuclear DNA data, the author inferred historical processes in the second part that may have shaped the eBook evolution of the Caricaceae and explain their current geographic distribution. The last part is 85,59 € | £71.50 | $89.00 dedicated to the evolution of chromosome numbers in the Caricaceae and includes counts for [2]85,59 € (D) | 85,59 € (A) | CHF species from three genera (Cylicomorpha, Horovitzia, Jarilla) that have never been investigated 94,00 before. Available from your library or springer.com/shop MyCopy [3] Printed eBook for just € | $ 24.99 springer.com/mycopy Error[en_EN | Export.Bookseller. MediumType | SE] Order online at springer.com / or for the Americas call (toll free) 1-800-SPRINGER / or email us at: [email protected]. -

Secreted Molecules and Their Role in Embryo Formation in Plants : a Min-Review

Secreted molecules and their role in embryo formation in plants : a min-review. Elisabeth Matthys-Rochon To cite this version: Elisabeth Matthys-Rochon. Secreted molecules and their role in embryo formation in plants : a min- review.. acta Biologica Cracoviensia, 2005, pp.23-29. hal-00188834 HAL Id: hal-00188834 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00188834 Submitted on 31 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright ACTA BIOLOGICA CRACOVIENSIA Series Botanica 47/1: 23–29, 2005 SECRETED MOLECULES AND THEIR ROLE IN EMBRYO FORMATION IN PLANTS: A MINI-REVIEW ELISABETH MATTHYS-ROCHON* Reproduction et développement des plantes (RDP), UMR 5667 CNRS/INRA/ENS/LYON1, 46 Allée d’Italie, 69364 Lyon Cedex 07, France Received January 15, 2005; revision accepted April 2, 2005 This short review emphasizes the importance of secreted molecules (peptides, proteins, arabinogalactan proteins, PR proteins, oligosaccharides) produced by cells and multicellular structures in culture media. Several of these molecules have also been identified in planta within the micro-environment in which the embryo and endosperm develop. Questions are raised about the parallel between in vitro systems (somatic and androgenetic) and in planta zygotic development.